New data on Agent Orange use during the US’s secret war in Laos

Published: October, 2024

Successive US governments have been reluctant to come clean over the human and environmental cost of the secret war in Laos. As Philipp Barthelme explains, declassified spy satellite imagery can now help us track potential dioxin exposures from the use of Agent Orange.

Contents

Introduction

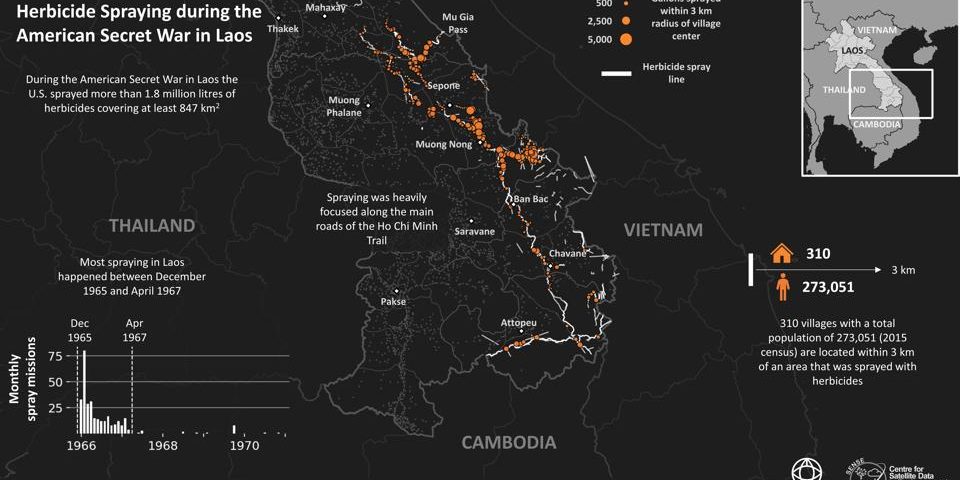

During the Vietnam War, the US military sprayed more than 74 million litres of Agent Orange and other herbicides, causing detrimental and ongoing environmental and health effects that are thought to have affected millions of Vietnamese people, as well as American military personnel. However, many questions remain over the extent and impact of the spraying during the American Secret War in neighbouring Laos. Unlike in Vietnam, Laotians affected by the herbicide spraying have received little to no support in the past, despite recent surveys indicating that thousands could still be affected by congenital birth defects associated with Agent Orange exposure.

This report uses declassified US spy satellite imagery taken during the war to identify areas sprayed with herbicides in southeast Laos. The aim is to revise declassified spraying records to provide a completer and more precise picture of the spraying in southeast Laos. This will help guide the surveys and ground samples that are needed to understand past harm and current risks, and therefore the support required by the long-neglected communities affected by herbicide spraying.

Herbicides and the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War, which ended in 1975, saw the US military’s large-scale use of herbicides in what was codenamed Operation Ranch Hand. These chemicals, including the notorious Agent Orange, were sprayed to defoliate forests and destroy crops, with the aim of disrupting enemy operations. The impact of this spraying was profound, leading to environmental devastation and severe health issues among the Vietnamese population as well as in US veterans.

The main threat the herbicides posed to humans did not originate from the defoliating chemicals themselves but from the chlorinated dioxin 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). TCDD is a highly toxic persistent organic pollutant that was a by-product of herbicide production and present in Agent Orange and many of the other herbicides. People were exposed to TCDD through direct contact with the sprayed herbicides, consumption of contaminated food and water, and the inhalation of airborne particles. Because TCDD persists in the environment and can be passed from mother to child, its use has resulted in generational health effects. Common conditions linked to exposure include cancers, birth defects, immune system disorders and reproductive issues.

It is estimated that between 2.1 and 4.8 million Vietnamese, 500,000 Laotians and tens of thousands of American military personnel could have been exposed to TCDD during the Vietnam War. In 1991 the US Congress passed the Agent Orange Act providing benefits to American veterans for illnesses associated with dioxin exposure. Laos was added as a presumptive location for Agent Orange exposure in the PACT Act passed in 2022, giving veterans who served in Laos between December 1965 and September 1969 presumed exposure, whereas previously they had to prove exposure. Since 2007, while never officially accepting responsibility, the US has provided more than $139 million to support Vietnamese people with disabilities in areas where Agent Orange was heavily sprayed. Laotian people just across the border from Vietnam, who were exposed to the same herbicides during the war, did not receive any support from the US until 2021.

Herbicides in Laos

During the US’s secret war in Laos, the US military conducted extensive herbicide spraying campaigns; these primarily took place between 1965 and 1967. The operations, which were part of the broader Operation Ranch Hand, aimed to reveal North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao troops by defoliating the dense jungle along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the main supply route of the North Vietnamese troops to South Vietnam (Figure 2).

The defoliated supply routes were subsequently bombed with huge quantities of general purpose and cluster bombs. In total, more than 2 million tons of bombs were dropped on Laos, making it the most bombed country per capita in history. Dealing with the legacy of UXO has been a major focus of international donors and the Laotian government, which even introduced an 18th Sustainable Development Goal, “Lives Safe from UXO”, to address the issue. Despite these efforts it is estimated that only 10% of contaminated areas in Laos have been cleared so far.

At the same time, the legacy of herbicide sprayings in Laos has not been well studied or addressed. The spraying in Laos was officially denied by the US during and even after the war, and was only publicly acknowledged in 1982 as part of a report on The Air Force and Herbicides in Southeast Asia by William Buckingham. Most of the spraying happened in remote areas with poor infrastructure and health care, and many of the affected communities are from small indigenous ethnic groups. In 2014 the Laos Agent Orange Survey began surveying villages in heavily sprayed districts to identify people with congenital birth defects associated with dioxin exposure. While the survey is ongoing, initial results indicate that thousands of people could still be affected today.

Using declassified US spy satellite imagery to track herbicide spraying

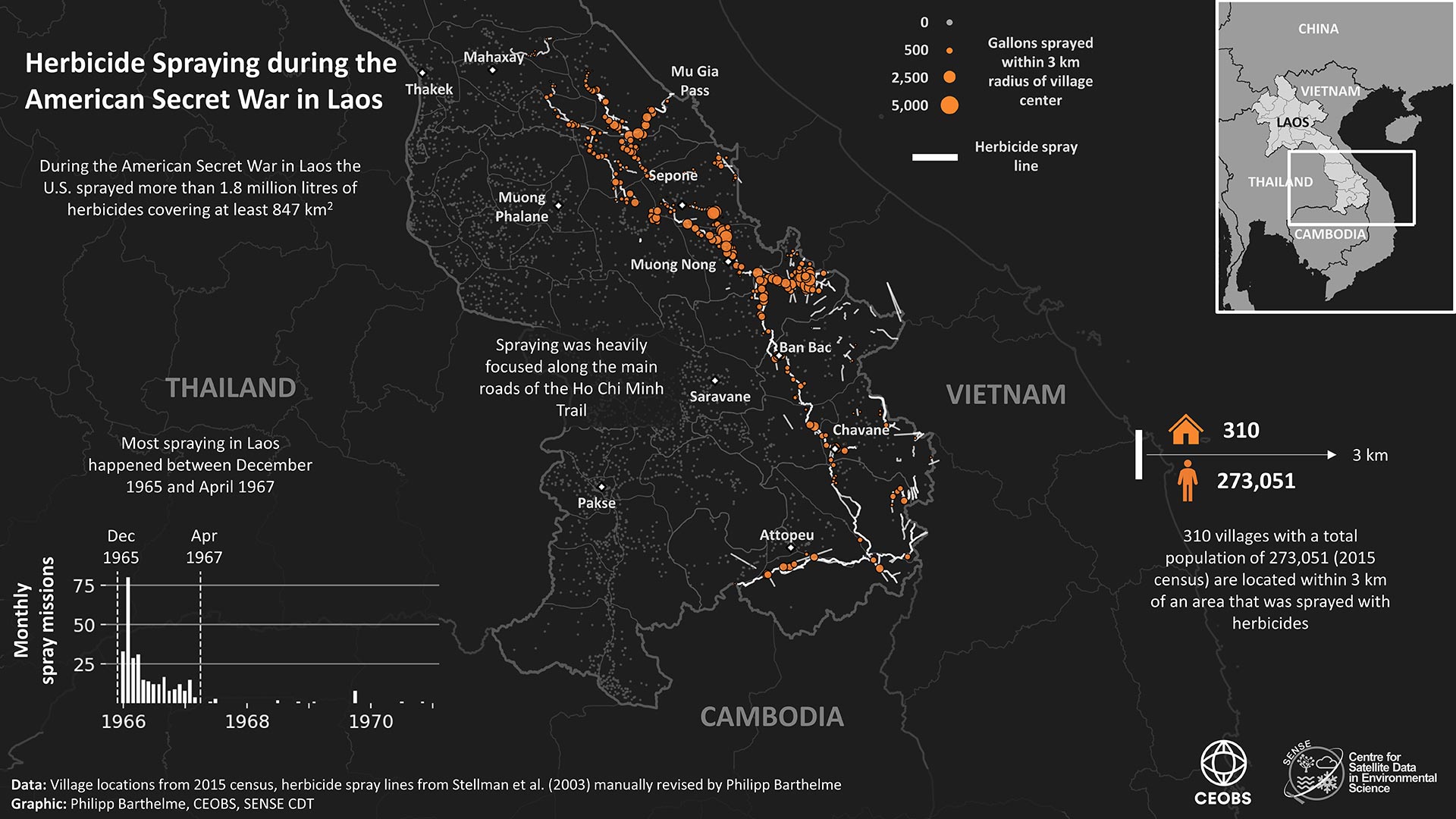

The recently declassified KH-4 (CORONA) and KH-9 (HEXAGON) satellite programmes now provide high-resolution imagery from the 1960s and 1970s. Originally intended for Cold War reconnaissance, these images have recently been used to identify locations of Vietnam War-era bomb craters. However, the images can also be used to identify herbicide spraying.

The defoliated areas appear brighter in the imagery as they reflect more light, while healthy vegetation appears darker as it absorbs more light. Where multiple images from different times are available, the transition from healthy to defoliated forest and back to dark as vegetation regrows can be observed. The distinct shape of a spray line, about 80 m wide and 16 km long, is also helpful for identification. As spray missions were commonly conducted by two or three planes flying in formation, the parallel running spray lines are often easy to identify in the CORONA imagery. In cases where imagery is insufficient or obscured by clouds, the context of nearby roads and footpaths can help determine likely areas of spraying.

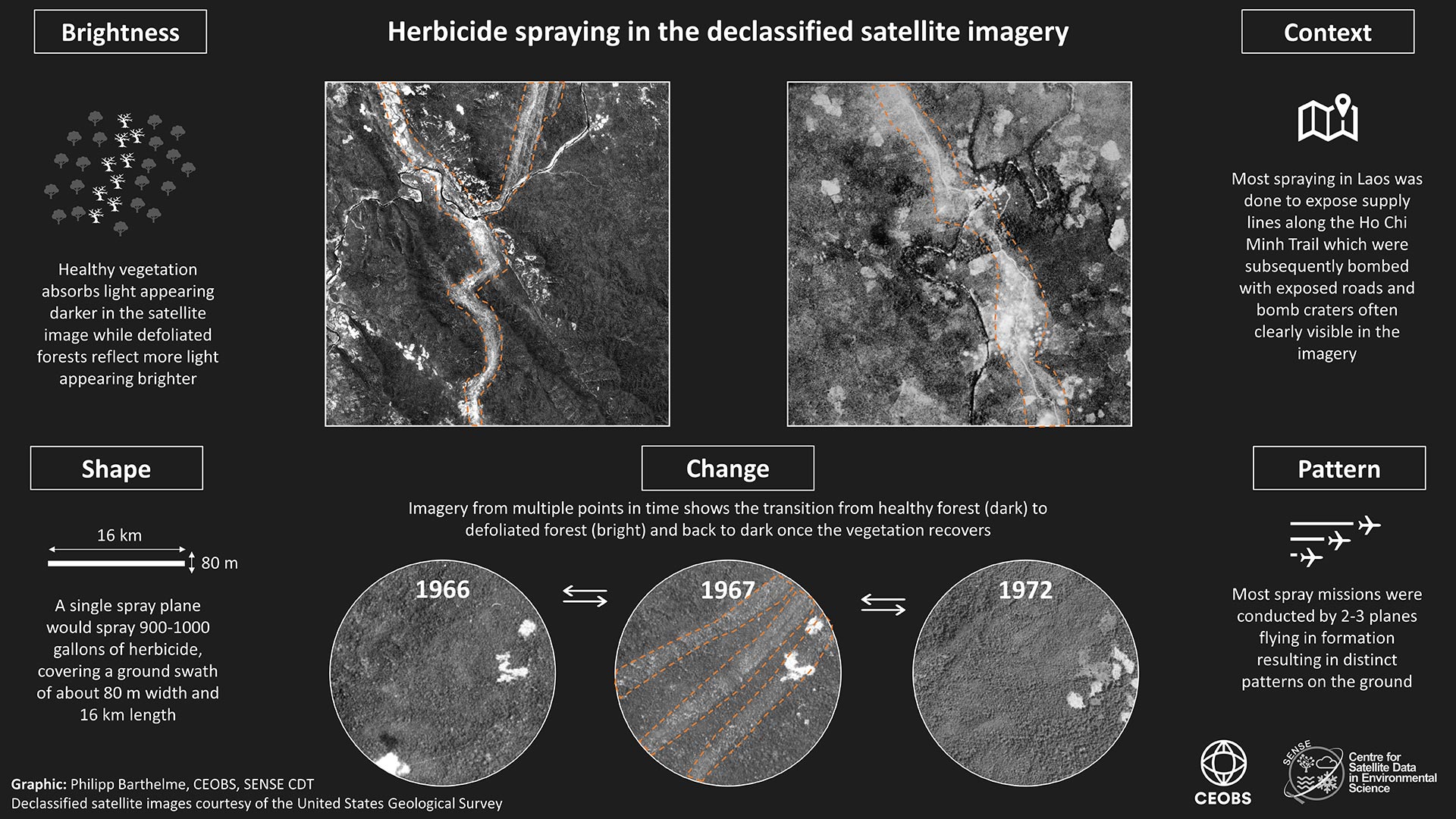

Declassified US military records on the herbicide spraying include records for 226 spray missions in Laos encompassing 319 individual spray runs.1 However, these records are believed to be incomplete and often imprecise. We investigated this by comparing the spray records with visual evidence of spraying in the declassified CORONA imagery. We acquired and processed 36 CORONA images with the aim to cover each location in southeast Laos with a minimum of one image in 1966 and one image in 1967. We compared the recorded spray path for each spray run with visual evidence of defoliation in the CORONA imagery (Figure 4). We then adjusted each recorded spray path based on this visual evidence, and context such as roads, to reflect as closely as possible the actual flight path that we believe was taken during the spray run. Finally, we documented any visual evidence of spraying in the CORONA imagery that we could not associate with a declassified spray record.

Summary of results

We revised 69% of the recorded spray runs, relying on direct visual evidence of the spraying in the declassified imagery, visible for 57% of spray runs, as well as additional context such as locations of roads. This additional context was often useful as for 46% of spray runs the area of interest was either fully or partly covered by clouds or the only cloud-free imagery was taken more than a year after the spraying making spray lines more difficult to identify. We identified 39 spray runs for which we suspect the recorded coordinates were incorrect or partly missing, mostly due to typos. We corrected 25 of those based on visual evidence and other declassified information. Moreover, we identified nine instances of unrecorded spraying, meaning visual evidence of spraying in the CORONA imagery that we could not attribute to any of the recorded spray runs.

Key findings

1. Official US spraying records are imprecise

Our analysis revealed substantial differences between the recorded spray lines and the visual evidence observed in declassified CORONA imagery. The recorded spray lines commonly follow a straight line between their start and end locations with few or no recorded turn points in between. However, the visual evidence shows that spraying in Laos rarely followed straight lines and instead closely tracked the winding roads through the difficult terrain, frequently deviating many kilometres from the recorded spray paths in the process (Figure 5). This difference is critical because most of the herbicides sprayed during spray runs with two aeroplanes, the most common setting for spraying in Laos, would have been concentrated within a swathe about 200 m wide. Accurate and precise identification of these spray lines is essential to assess the exposure levels of dioxin in villages during and after the war, and to pinpoint locations for soil sampling for residual dioxin contamination. Without precise data, it is challenging to study the potential impacts on local populations and the environment.

Spraying was intense along roads

The US’s focus of spraying along roads, which is clear in the CORONA imagery, is further supported by declassified CIA documents and the oral testimonies of locals who observed the spraying at the time. The main implication is that, compared to what the spraying records tell us, spraying in Laos took place over a smaller area but at higher concentrations, which may have translated into relatively higher exposures for affected communities. As many villages were and still are located close to the roads, the amount of herbicide sprayed within 1 km of a village increases by 34% when using our revised data instead of the recorded spray lines.2 While many villages were abandoned during the war, spraying in Laos happened very early during the war, often preceding the bombing, so people could have been exposed to dioxin before they left or after they returned. Moreover, people often stayed within a few kilometres of their villages, continuing to forage for food and fish in nearby rivers that could have been contaminated by herbicide spraying in the area.

Unrecorded and corrected spraying

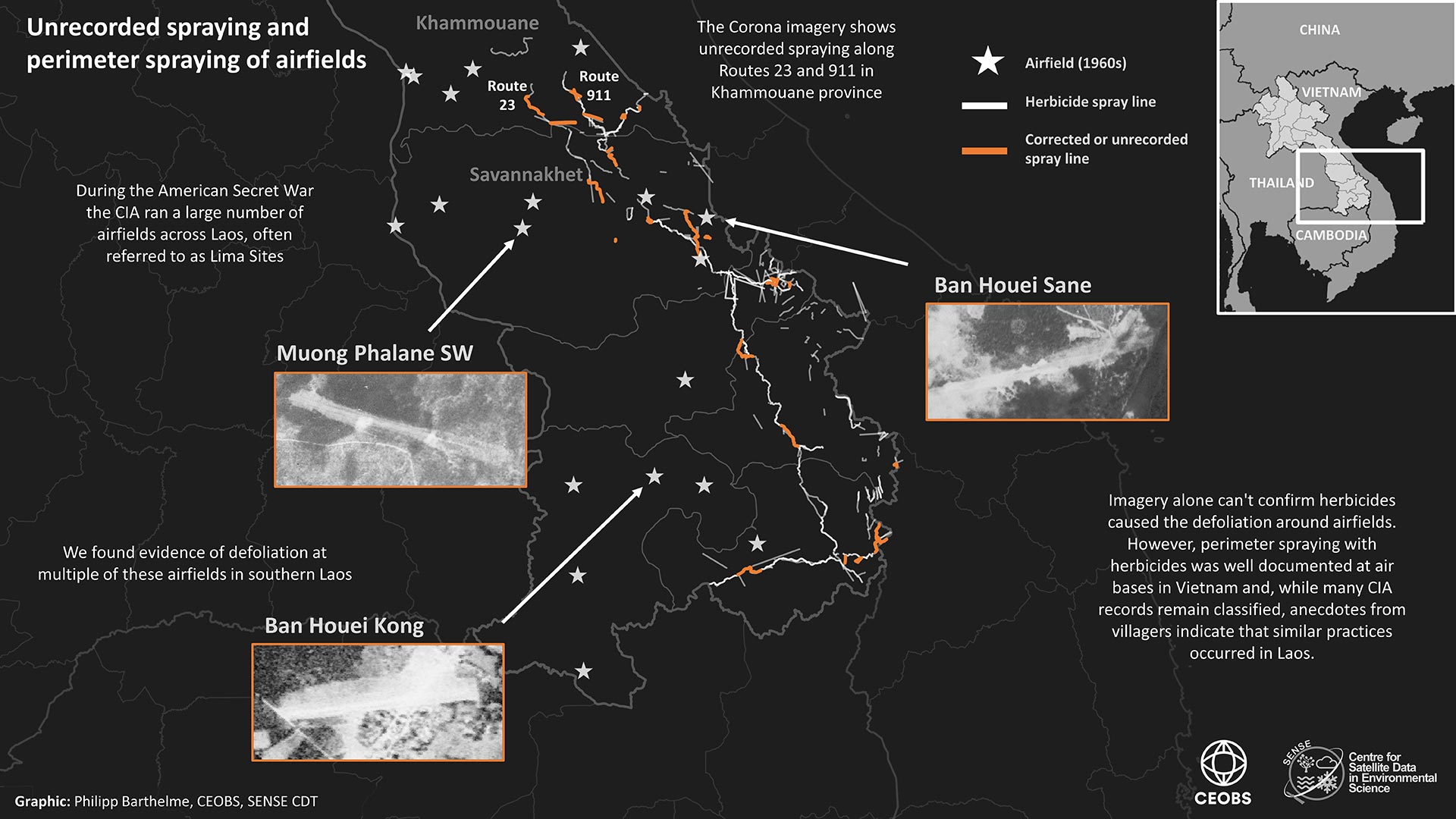

Despite their imprecision, we found the recorded spray lines to be comprehensive as we only found evidence of a small amount of unrecorded spraying, particularly after correcting record errors such as typos. Most of the unrecorded and corrected spraying was located close to existing spray lines; the most notable updates were in Khammouane Province where we observed additional spraying in the area of Routes 23 and 911.

Our analysis mainly relied on CORONA imagery of southeast Laos in 1966 and 1967. While this covers most of the declassified recorded spraying by the US Air Force, this did not allow us to investigate any potentially unrecorded or still classified spraying in central or northern Laos. There is evidence, such as oral records of veterans, indicating that the CIA might have conducted its own herbicide spraying in these parts of Laos.

Herbicide spraying along the perimeter of airfields

While we did not have the resources to acquire and process additional CORONA imagery to investigate potential spraying by the CIA in central and northern Laos, we did identify evidence of defoliation at some of the CIA-run airfields in southern Laos. We suspect this to be due to perimeter spraying with herbicides. This is difficult to confirm with certainty as we can observe the defoliation in the imagery but not always its cause. While the characteristic spray lines help with identification for spraying with fixed wing aircraft, this is not applicable for perimeter spraying, which was often done on the ground or by helicopter.

Airfields and military bases were particularly relevant, especially if herbicides were stored on the bases, as was the case for Danang and Bien Hoa in Vietnam. There, large volumes of herbicides leaked into the environment resulting in so-called dioxin hotspots affecting thousands of people working on these bases as well as civilians living nearby. The contamination only recently began to be brought under control through remediation of the affected areas, which the US supported with more than $300 million. While the quantities of herbicides that were potentially stored and sprayed at airfields in Laos would have been much smaller, the remaining dioxin contamination could still be high enough to be dangerous to people. The CIA should declassify all records related to herbicide spraying in Laos, and soil sampling should be undertaken at affected airfields to ensure the safety of people living nearby.

What needs to happen now?

The herbicide spraying during the US’s secret war in Laos has had long-lasting impacts, and it is crucial that comprehensive efforts are undertaken to address the consequences. We recommend the following actions to ensure that the full scope of the spraying and its aftermath are properly addressed and that those affected receive the support they need:

1. Funding of declassified satellite/aerial imagery

The US should fund the digitisation of all available CORONA/KH-9 satellite imagery covering Laos. The imagery is already declassified and the film rolls only need to be scanned, a service provided by the United States Geological Survey for $30 per image. The total cost of this would therefore be relatively small, in the thousands of dollars, but this can be prohibitive for NGOs and researchers. Moreover, more effort should be made to make the higher resolution declassified U-2 aerial imagery more usable for researchers.

2. Declassification of CIA records

To allow a comprehensive understanding of the secret war in Laos, the US should declassify all remaining CIA records related to this period. This transparency is necessary to uncover the full extent of the herbicide spraying operations and to facilitate historical accuracy and accountability.

3. Increased survey work

Support for more extensive survey work to identify those impacted by the herbicide spraying in Laos is urgently needed. Current efforts have revealed a significant disparity in the identification and support of affected individuals in Laos compared to Vietnam. Additionally, soil samples from airfields and heavily sprayed areas should be analysed to ensure nearby communities are not affected by residual contamination.

4. Support for affected individuals

The disparity between the past support provided by the US government to victims in Vietnam and those in Laos is stark and unjust. Victims in Laos deserve the same level of assistance and recognition as those in Vietnam. While this disparity was partly addressed by the 2021 Victims of Agent Orange Relief Act, more work is needed to ensure the provided funds are reaching all affected people.

5. Raising awareness and US responsibility

More should be done to raise awareness of the herbicide spraying in Laos. This topic should be included in educational curricula alongside discussions of Agent Orange spraying in Vietnam. The US has a responsibility to acknowledge its actions and to ensure that the historical narrative includes the experiences of affected Laotians.

Philipp Barthelme is a PhD candidate in the SENSE Earth Observation CDT at the University of Edinburgh and has been researching the impacts of Vietnam-era wars in Southeast Asia. CEOBS are co-supervisors to Philipp, who conducted this work during an internship with us. Thanks to Susan Hammond for her valuable advice during the project and to Jeanne Stellman for providing her version of the HERBS files (see Stellman et al. (2003)). Thanks to the United States Geological Survey (USGS) for providing the CORONA imagery and to the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies (CAST) at the University of Arkansas for access to their tool to georeference the imagery.

- See Stellman et al. (2003) “A mission is a sequence of records that describes a single application of a given quantity of a specific type of herbicide along a specified route on a single day”. A mission can encompass one or more planes and each mission can include multiple spray runs. The spraying is uninterrupted during a run but is turned off in between different runs so that one mission could include multiple spray runs that were not physically connected.

- We use village locations from the 2015 census for this calculation.