The emerging environmental consequences of the Israel-Iran war

Published: June, 2025 · Categories: Publications

A week into the conflict between Israel and Iran we review some of the key environmental issues and trends, moving beyond risks from attacks on nuclear facilities to the wider consequences of both parties’ military conduct.

Contents

Introduction

The war between Israel and Iran began on the 13th June after Israel attacked dozens of targets in Iran with the stated aim of destroying Iran’s nuclear programme. To date, Israel has primarily relied on air strikes through fixed wing aircraft and drones, some covertly launched from within Iran. Iran has responded by firing ballistic missiles and drones, with both sides suffering civilian casualties. As the war has progressed it has become evident that Israel is targeting a far wider range of sites than just those linked to Iran’s nuclear programme. For its part, Iran has targeted military and energy facilities in Israel, although the effectiveness of these attacks has been reduced by Israel’s missile defence system.

Environmental concerns have initially focused on the implications of military strikes against nuclear facilities, leading the IAEA to state that: “… nuclear facilities must never be attacked, regardless of the context or circumstances, as it could harm both people and the environment.” However, in broadening the scope of targets, Israel has also broadened the scope of potential environmental risks and this post offers some examples of the risks associated with damage to military facilities and energy sites. Should the war intensify or become prolonged, we expect to see an increasing number of reverberating harms, for example those linked with damage or disruption to critical civilian infrastructure, as well as potential damage to neighbouring countries and the marine environment.

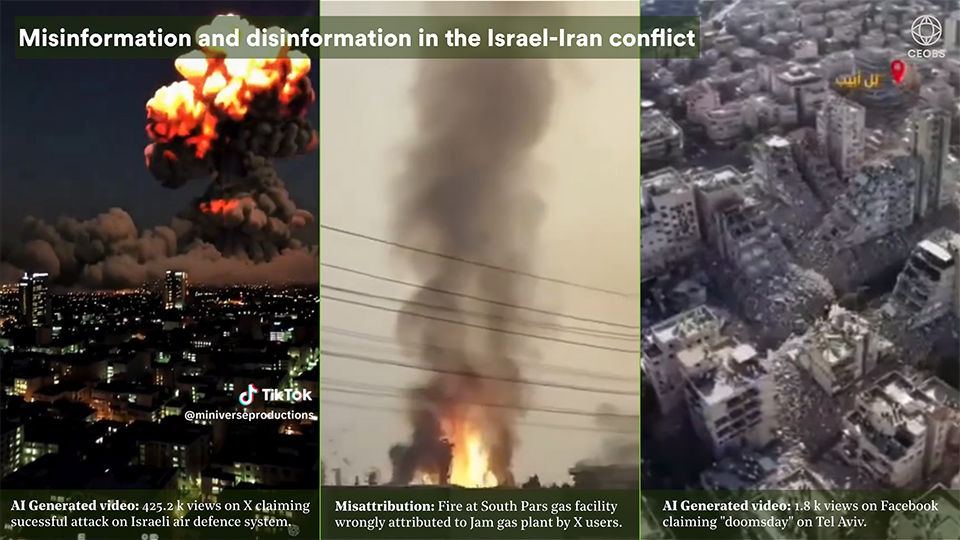

This overview is an initial scoping exercise based only on remote analysis and the existing literature. In places, such as the impact of ballistic and interceptor missiles on the upper atmosphere, it is speculative. OSINT analysis of the impacts has been hampered by the online information environment, which has seen a high volume of disinformation, AI generated content and miscaptioned footage.1 Finally, in many of the examples below, the risks they pose to people and the wider environment are heavily influenced by the capacity of the state to mitigate them.

Risks from the destruction of nuclear facilities

At the time of writing, nuclear risks have been the primary focus of the war’s environmental narrative. Iran has an extensive range of facilities linked to its uranium enrichment programme, together with one operational nuclear power plant at Bushehr. Its Tehran Research Reactor produces medical isotopes and runs on 20% enriched uranium, whereas the Khondab (Arak) heavy water reactor remains under construction. In spite of this it was targeted overnight on the 18th June, no nuclear material was onsite. The IDF issued a warning to employees and nearby residents.

As has been the case in Ukraine, the IAEA has been providing commentary on the potential risks based on data from the national authorities, the staff it retains in-country and analysis of satellite imagery. A key distinction for the IAEA has been whether the risks are contained onsite, or may spread off site. For its part, Israel claims that it is “taking precautions to avoid triggering a nuclear disaster”.

To date, attacks have been documented at Natanz, which houses two active uranium enrichment plants, with a third under construction. The IAEA reports damage to the Pilot Fuel Enrichment Plant and potential damage to its underground Fuel Enrichment Plant, where it has suggested that all 15,000 gas centrifuges may have been damaged by the sudden loss of power. The IAEA believes that there is radioactive and chemical contamination at both sites. The gas centrifuges used to enrich uranium to fuel and weapons grade use uranium hexafluoride (UF6), which is highly reactive. If released from storage or centrifuges, and on contact with moisture in the air, it transforms into hydrogen fluoride and uranyl fluoride gas.

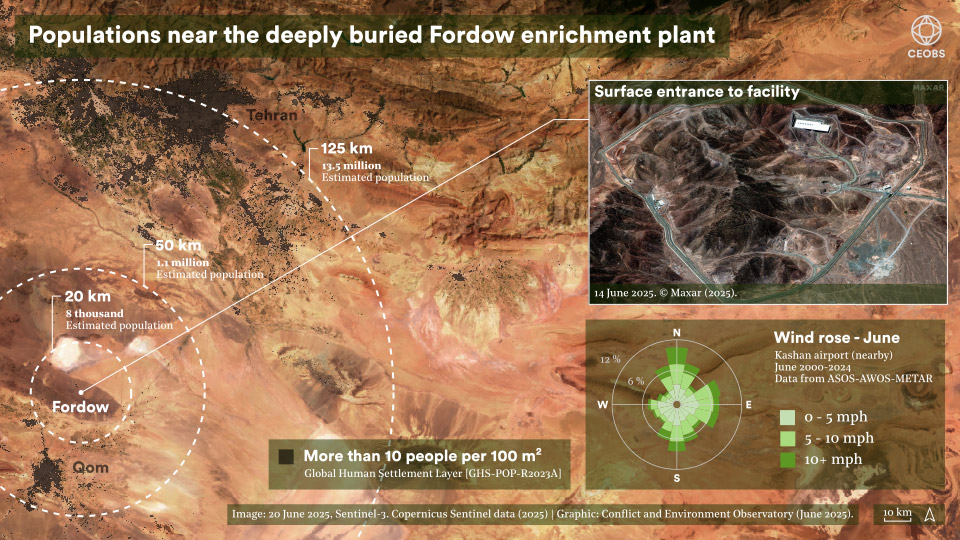

Typically, exposure to uranyl fluoride gas presents a primary risk from its chemical toxicity, rather than radioactivity, unless it is highly enriched in the isotope uranium 235, as may be the case in some of Iran’s facilities. Uranium 235 primarily emits alpha radiation, while this can be blocked by the skin it is dangerous when inhaled. At present little information is available on releases from the damaged facilities. A second and more deeply buried enrichment plant at Fordow is gaining increasing attention as the potential focus for an attack using US bunker busting bombs. As with Natanz, the primary nuclear risk is likely to be an escape of uranyl fluoride composed of highly enriched uranium. A more deeply buried site, Kūh-e Kolang Gaz Lā, also known as Pickaxe Mountain, was under construction a few kilometres south of Natanz and may be beyond the reach of US airstrikes.

Several other nuclear sites likely to have contained uranium compounds in solid and gaseous forms, as well as other potentially hazardous materials, have also been damaged. This includes the Esfahan site where, according to the IAEA, four buildings were damaged on the 13th June, including its: central chemical laboratory, a uranium conversion plant, the Tehran reactor fuel manufacturing plant, and a UF4 to EU metal processing facility, which was under construction. As in Natanz, the IAEA suggested that off-site radiation levels remain unchanged. On the 18th June it was announced that two centrifuge production facilities had also been hit: the TESA Karaj workshop and the Tehran Research Centre.

Environmental risks from damaged military facilities

Israel has targeted a substantial number of Iranian military facilities, this includes missile bases, airfields, weapons storage sites and facilities involved in military production. The environmental consequences of attacks on military sites are highly variable and depend on the materials and activities present at each site. While many of the sites attacked to date show evidence of secondary explosions and fires these will not have burned or destroyed all materials of concern, and may have generated secondary pollution. Typical pollutants for such sites include fuels, oils and lubricants, heavy metals and energetic materials, and PFAS and PFOA; fires can add dioxins and furans. While many military installations are located at distance from urban areas, a number of damaged sites are in proximity to cities, thus increasing exposure risks for the public if pollutants are transported offsite. It is also the case that the use of these complex polluted sites may change over time, a reminder that pollution risks can stretch well beyond the immediate conflict.

One notable concern in the context of the war are pollution risks associated with damaged missile facilities. Iran has a diverse range of solid and liquid fuelled ballistic missiles. Many liquid missile fuels are highly toxic. For example, some of Iran’s short-range missiles are based on Soviet SCUD designs, which use unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine as the fuel and inhibited red fuming nitric acid as the oxidizer. These and other liquid missile fuels have proven highly problematic to manage and dispose of in settings including Afghanistan, Libya and Ukraine.

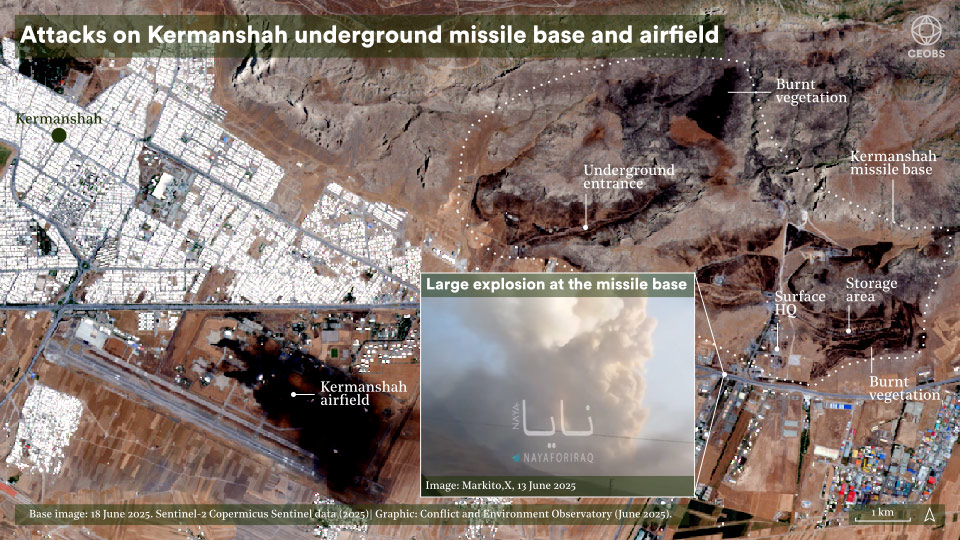

Damaged missile sites include the Tabriz missile compound, which was attacked on the 13th and 17th June, and the underground facility at Kermanshah, also targeted on the 13th and again on the 15th, and where extensive burn marks can be seen, as well as a number of destroyed buildings and damage to what appear to be two tunnel entrances. Other targeted sites include Ghadir ballistic missile base near Tehran and an army base at Zanjan, where secondary fires involving munitions and fuels were reported after a strike on the 16th.

A number of Iranian airfields have been targeted, airfields contain fuel stores with the risk of fires and spills, as well as specific pollutants such as PFAS “forever chemicals” from the use of firefighting foams. The extent to which attacks may generate or mobilise pollutants is highly variable. Attacks at airfields like Kermanshah on the 18th June have resulted in fires and the destruction of military aircraft. An attack on military aircraft and hangers at Tehran’s Mehrabad International Airport on the 14th generated fires and smoke plumes, while a strike at Hamdan airbase a day earlier caused extensive damage to the facility.

Weapons storage and production sites have also been targeted. Including a storage complex near Qom on the 16th, much of which is thought to be underground, and the Khojir Missile Production Complex southeast of Tehran, where a large fire was visible overnight on the 17th June, which left burn scars and damaged buildings.

This limited selection of military sites should be viewed as simply indicative of the nature of the damage thus far and its potential to generate environmental risks, primarily related to human and ecological exposure to toxic remnants of war.

Environmental risks from damage to fossil energy infrastructure

Iran is a major oil and gas producer with substantial known reserves that are mainly situated in the south west of the country. It has well developed fossil fuel infrastructure including oil refineries and storage plants, gas processing plants, export terminals on the Persian Gulf and an extensive network of oil and gas pipelines. At the time of writing attacks on these sites had been relatively limited but could be expanded in the event of a major escalation. Because of the scale of Iran’s exports, this would lead to a rise in global prices.

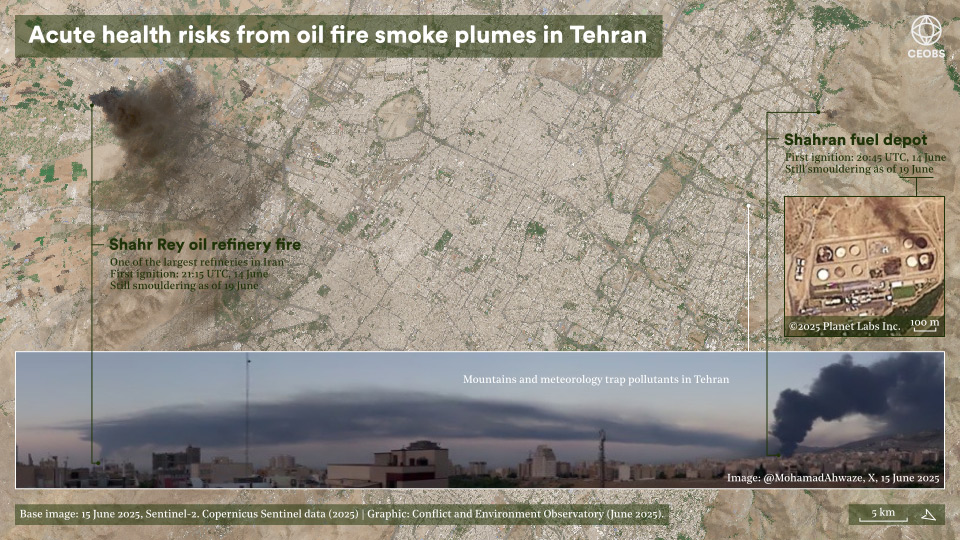

Major oil fires — whether at refineries or storage sites — generate a wide range of pollutants, including particulate matter, NOx, nitrous acid, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, VOCs such as formaldehyde, and potentially dioxins, furans, hydrocarbons and PAHs. These impact air quality and downwind fallout from plumes can pollute soils and waters. Fires and damage to gas infrastructure can generate CO2 and lead to methane releases, which is a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2 but shorter-lived in the atmosphere.

A June 14th attack on the state owned Tehran Refinery, located in Tehran’s Shahr-e Rey district, led to a major fire, visible on the 15th June. One of the country’s oldest refineries, it has a refining capacity of 225,000 barrels per day. A second fire burned simultaneously at the Shahran fuel and gas depot, northwest of central Tehran. The depot is one of Tehran’s largest fuel storage and distribution hubs with a capacity of 260 million litres across 11 storage tanks. Satellite imagery from the 18th June confirms the destruction of four fuel storage tanks with evidence of oil residues on the ground, although likely contained by a berm, and a persistent smoke plume.

Tehran’s urban layout and geography significantly influence the mobility of air pollutants. The city of 10 million is surrounded by the Alborz mountain range, which frequently traps smog and pollution within the city. High-rise buildings also hinder wind flow, reducing the dispersion of pollutants and worsening air quality. Air pollution from the two oil facility fires and any future incidents need to be considered in this context.

A facility on the South Pars gas field, which is the world’s largest and operated jointly with Qatar, was hit on the 14th June, Iranian state media reported that a fire had broken out ‘in one of the four units of Phase 14 of South Pars’, halting production of 12 million m3 of gas. Analysis suggests that there has been damage to a processing centre. The focus of the strike was a pipeline regulating building; two wells to the north of the location no longer appear to be operational or flaring. Imagery of another nearby site, the Fajr Jam gas plant, one of Iran’s largest gas processing facilities, reveals damage at the facility and to the surrounding area by the 15th June, including scorched vegetation on a nearby hillside and damage to some of the processing infrastructure.

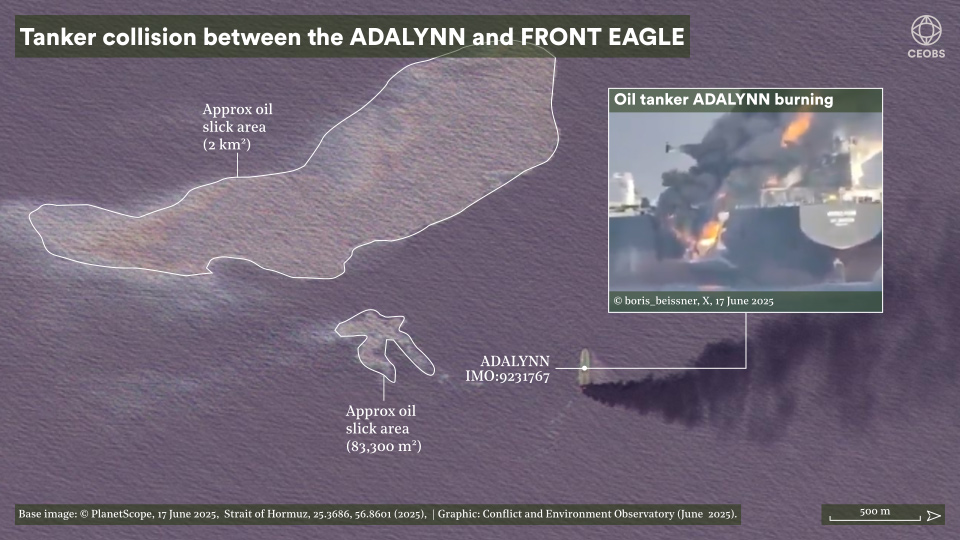

At the time of writing there had been no reported attempts to strike offshore platforms or tankers. If targeted, oil pollution could result in serious harm to the Persian Gulf’s marine environment, which is already under pressure from the oil industry. However, on the 17th June, two oil tankers collided in the Persian Gulf triggering a fire and spill from the ADALYNN, which generated an 8 km oil slick. It is thought that GPS spoofing linked to electromagnetic warfare may have contributed to the collision and may thus present an ongoing risk for shipping in the area.

Impact of ballistic and interceptor missiles on the upper atmosphere

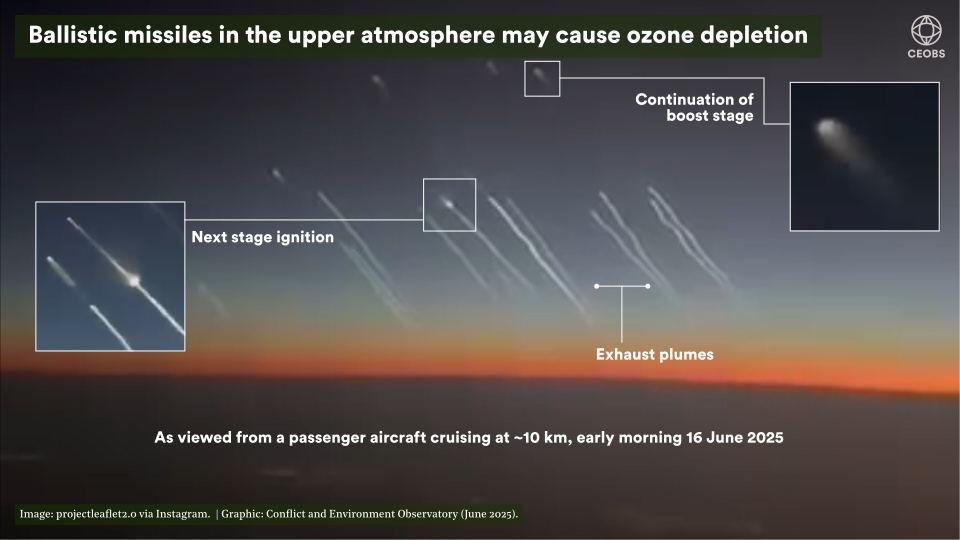

The medium range ballistic missiles launched by Iran may pose threats to the upper atmosphere. The stratosphere and mesosphere are particularly sensitive to the injection of contaminants: removal processes are slow partly because there is no rainfall. Pollution can alter chemistry, temperature and circulation patterns, the exact impact depending on the composition of fuels or materials, and the altitude they are released at. This could be at launch, during boosting, because of ablation, or following explosive interception by THAAD systems. Understanding the impact from hypersonic missiles will likely be even more complex given that they do not follow a parabolic arc, but may concentrate pollutants at specific altitudes.

There is very little understanding — at least in the open scientific literature — of how mass missile usage may impact the atmosphere. However, as the missiles used to cover the distance to Israel are solid-fuel based, the emerging studies into satellite launches are relevant analogues. Pollutants of particular concern include aluminium oxide and black carbon (i.e. soot) particles, and gaseous reactive nitrogen and chlorine. Likely the most significant impact is how these pollutants act together to deplete the stratospheric ozone layer. The impact of rarer elements is a significant unknown; for example niobium or hafnium have been observed and are also components in the super-alloys used for rocketry. Where missiles are intercepted there are additional contaminants of concern such as perchlorate – especially at lower altitudes where human or environmental exposure may occur.

Environmental risks from Iranian strikes on Israel

Iran has retaliated against Israel using a mixture of ballistic missiles and drones, the latter being used primarily to occupy Israeli air defences to increase the chances of Iran’s ballistic missiles reaching their targets. By the 19th, Iran was believed to have fired more than 400 missiles, although half of these were in Iran’s initial barrage at the outset of the conflict. Iran’s long range attacks on Israel have caused civilian harm and damaged military and civilian infrastructure, and residential areas, although the majority of drones and missiles have been intercepted. During this first week, 43 impacts were reported from Iranian ballistic missiles or Israeli interceptors. Meanwhile, Israeli and allied forces had shot down more than 480 of around 1,000 drones launched, with 200 of these entering Israeli airspace. Of these, Israel claimed that none had impacted urban areas.

These statistics mean that Iran is facing a greater environmental footprint from the war than Israel but there have been environmentally relevant incidents. On the 15th June missiles hit the Bazan oil refinery complex near Haifa, triggering fires and pipeline damage. Two missiles also hit Haifa’s power plant. In response to the war, Israel shut down two of its three offshore gas fields, reducing domestic supply. Limited production was restarted on the 19th; Egypt’s fertiliser production had been impacted by the shutdown. A strike targeting the Mossad headquarters appears to have resulted in damage to a wastewater treatment plant in Herzliya on the 17th.

Damage to urban areas, including to commercial and residential buildings, can create inhalational hazards for people from pulverised building materials and combustion products. Israel banned asbestos in 2011 but it is estimated that it still has more than 100 million m2 of asbestos cement panels. Asbestos is a problem in many parts of the region and one that remains of substantial concern in Gaza.

Environmental trends to watch if the war continues

Water and sanitation infrastructure

At the time of writing, Israel does not appear to have directly targeted Iran’s water, sanitation and health (WASH) infrastructure. However, attacks have reportedly damaged buried pipes leading to wastewater discharges in cities. Damage to WASH infrastructure carries site specific environmental risks, as well as reducing civilian access to water. De-energisation and other forms of disruption can also impact sites, cyberattacks have been frequent and with 80% of its energy generated by natural gas, Iran’s grid may come under pressure. On the 18th June Israel targeted a power plant in Karaj, should this strategy be expanded it will place pressure on an electricity network that was already prone to blackouts.

Persian Gulf oil pollution

The war has already disrupted shipping in the Persian Gulf, which carries 20% of the world’s oil, as well as LNG. As noted above, electromagnetic warfare may be posing a risk to marine traffic. During the Iran-Iraq War, coastal and offshore oil and gas infrastructure was heavily targeted, damaging the marine environment. While the context of this war is markedly different, a substantial escalation could see such sites targeted, as well as tankers.

Reverberating effects of high oil prices

Sustained increases in oil and gas prices linked to conflicts can have complex outcomes for the global climate. While they can make projects economically viable in areas where hydrocarbons are expensive to exploit, they can also help drive the uptake of low carbon technologies and decarbonisation policies; they are also associated with a growth in production in politically stable regions, impacting the environment locally.

Conflict emissions ahead of COP30

Israel launched the war just as delegations were meeting in Bonn for the annual UNFCCC intersessional climate talks. While conflict and military emissions remain off the formal agenda for COP30 later this year, the climate movement has increasingly been making links between peace, security and the climate crisis. For many it has been Gaza that has helped facilitate this intersectionality but it seems inevitable that a prolonged war against Iran would encourage even greater attention on these linkages. And needless to say, the escalating air war is already generating emissions and displacing others, whether it’s through air strikes, diverted flights and shipping or the future carbon costs of reconstruction.

Overview prepared by Leon Moreland, Jonathan Walsh, Eoghan Darbyshire and Doug Weir. If you find our outputs useful, please consider donating to help support CEOBS’ continued work.

- Sources for the images used in the figure below: (left) https://x.com/Haider4PTI/status/1933657095921905775; (centre) https://x.com/HuzaifaViews/status/1933915418567086331; (right) https://www.facebook.com/maggie.carter3/videos/1407060593834366