The environmental costs of the war in Sudan

Published: May, 2025 · Categories: Publications, Sudan

The ongoing conflict in Sudan has profoundly impacted its environment but these consequences have received little attention. CEOBS has been monitoring the conflict’s environmental dimensions since October 2023 and this overview details key incidents and trends that pose risks to Sudan’s people and ecosystems.

Contents

Introduction

The war in Sudan between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) began on the 15th April 2023. The conflict has caused significant direct and indirect environmental damage, affecting both urban and rural populations. Impacts include increased deforestation, agricultural decline, pollution from damaged industrial and energy infrastructure, de-energisation events and the deterioration of health and sanitation systems.

The conflict has most heavily affected central and south-western states. While eastern states, such as Red Sea State, have seen little fighting, the influx of internally displaced persons (IDPs) has placed significant pressure on the environment. These pressures have also affected neighbouring countries that are hosting substantial refugee populations.

What began as intense urban warfare in Khartoum State quickly spilled over into other parts of the country. In December 2023, the RSF captured Al Gezira State, south of Khartoum, an area known as Sudan’s “breadbasket”, raising serious food security concerns — the SAF liberated Al Gezira State and Khartoum in early 2025. Meanwhile, southern and western states have experienced more intense fighting, particularly in Darfur, where serious human rights violations have been reported. The city of Al-Fashir has been under RSF siege since the early stages of the conflict and faced indiscriminate bombing.

Sudan’s proximity to the Sahel, the Horn of Africa, and the Red Sea means the conflict poses a serious risk of regional destabilisation, placing additional pressure on climate-sensitive ecosystems and fragile environments in neighbouring countries.

Our work on Sudan

We began monitoring the environmental impact of the conflict in Sudan in October 2023 and our Sudanese and British team have used our bespoke remote assessment methodology that integrates open-source intelligence, earth observation, and local expertise to identify and analyse environmental incidents and trends.

Some of the key incidents, themes and trends that we have identified are explored below.

Infrastructure and the built environment

Hazardous industrial and energy facilities

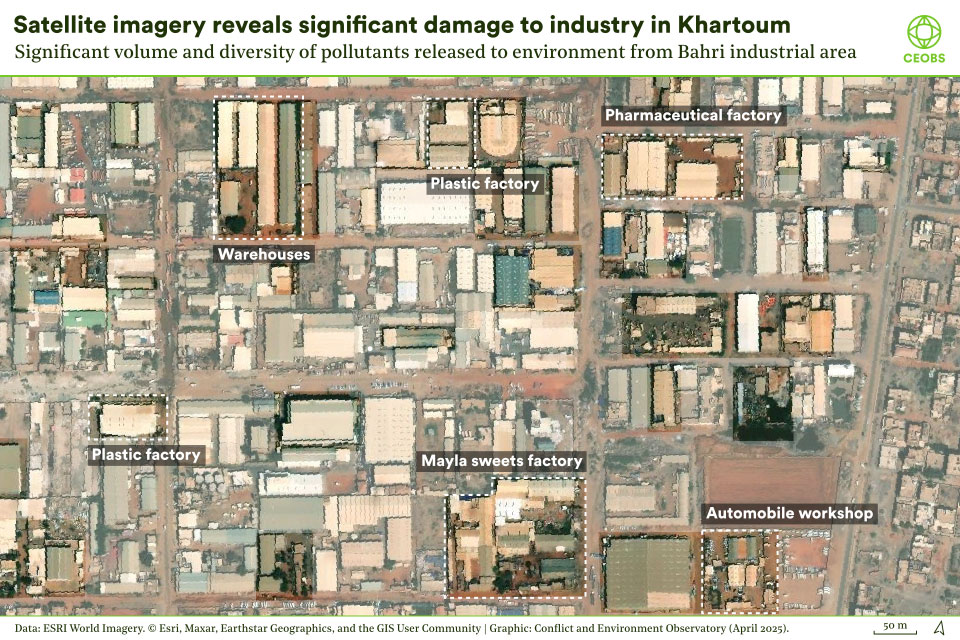

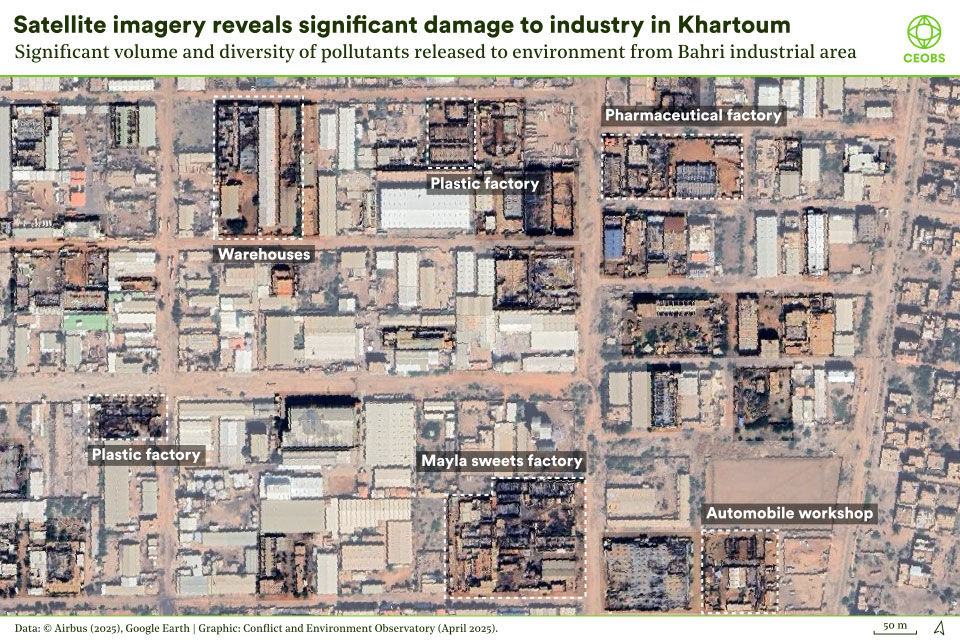

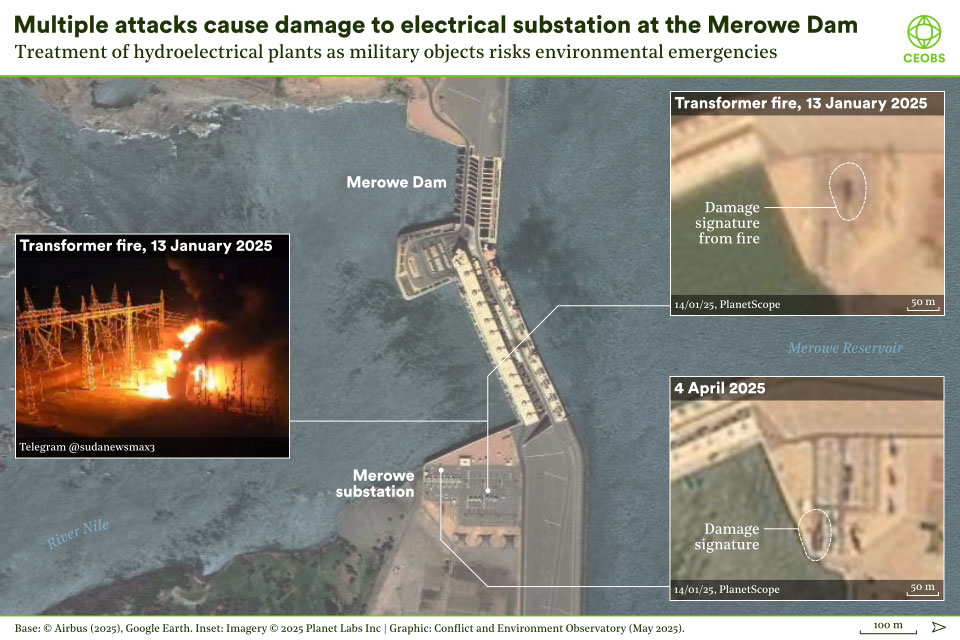

The war has impacted many hazardous facilities — including oil refineries, industrial and chemical plants, and power stations — through both physical damage and de-energisation, in places posing significant environmental risks. During our Khartoum assessment, which ran between April 2023 and January 2024, we identified 401 incidents across the city’s major industrial zones. In Khartoum’s urban areas, hazardous industrial sites are often closely interwoven with residential neighbourhoods, increasing the risk that local people may be exposed to pollutants when sites are damaged. Our analysis found that the Bahri Industrial Area, which comprises manufacturing, warehouse and energy facilities, was among the most heavily affected by the fighting.

Recurring highly damaging incidents at the Al Jili or Khartoum oil refinery mean that it is one of the few sites that has received attention. Located 45 km north of Khartoum it previously supplied 60% of the country’s gasoline, making it critical for Sudan’s oil sector. Recurring periods of fighting and occupation of the strategically important site have seen repeated large fires and resulted in substantial damage to the site’s infrastructure, which have also contributed to fuel shortages and disrupted energy supplies.

Damage to the site and its storage facilities has also led to contamination in and around it, while major oil fires have degraded air quality, releasing hazardous gases and pollutants. A huge fire on the 23rd January 2025 produced a smoke plume stretching more than 300 km, passing over Khartoum and darkening the skies of downwind communities.

The remote analyses we have undertaken can contribute to designing field assessments to determine the risks that war-damaged hazardous facilities pose to workers, communities and local ecosystems.

Building damage and debris management

Building damage and debris assessments are crucial for developing management and recovery plans. The widespread use of explosive weapons in urban areas has contributed to significant damage to the urban fabric of Khartoum’s conurbation. Pulverised building materials such as asbestos can create inhalational exposure risks for residents and workers, while disposing of large debris volumes can cause environmental impacts unless managed properly. UXOs and explosive ordnance are mixed in with the debris, complicating its management and posing risks to people returning home.

Debris volumes are expected to be significant. During our assessment of Khartoum State, we estimated that just one area of the city covering 57 km² contained at least 100,000 tonnes of debris; this was assumed to be an underestimate and to have subsequently increased. Sudan’s capacity for dealing with and managing solid waste was weak before the war and is unlikely to be able to deal with the volumes it has generated. Our debris assessment made use of advances in radar damage mapping; however a failure of the ESA’s Sentinel-1 satellite meant that the data required for Sudan was unavailable.

Risks from damaged water infrastructure

It is common for water and sanitation infrastructure to be damaged during conflict, physical damage, de-energisation and neglect all contribute, as can its deliberate weaponisation. For example, by March 2024 just one water treatment plant was working out of the 13 in Khartoum State.

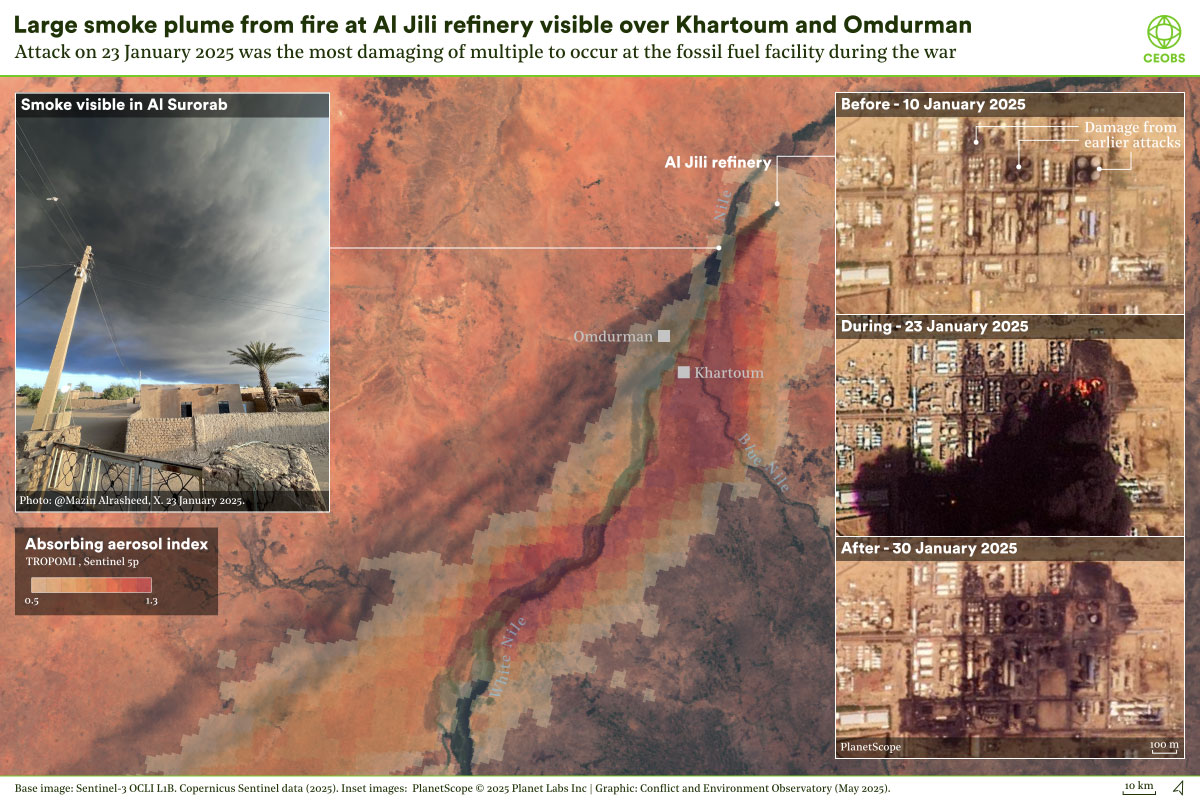

Sudan’s dam infrastructure, which is vital for agriculture, fisheries, transport and hydropower — it provides 70% of the country’s electricity — has not been spared. Upstream of Khartoum, the Jebel Aulia Dam became a strategic supply route for conflict parties. First attacked in November 2023, its proximity to the front line and to heavily populated areas raised ongoing concerns over a potential disaster. It also saw aerial attacks during the RSF’s chaotic withdrawal from Khartoum. In January 2025, the RSF attacked a transformer station at the Merowe Dam in Northern State, triggering widespread power shortages.

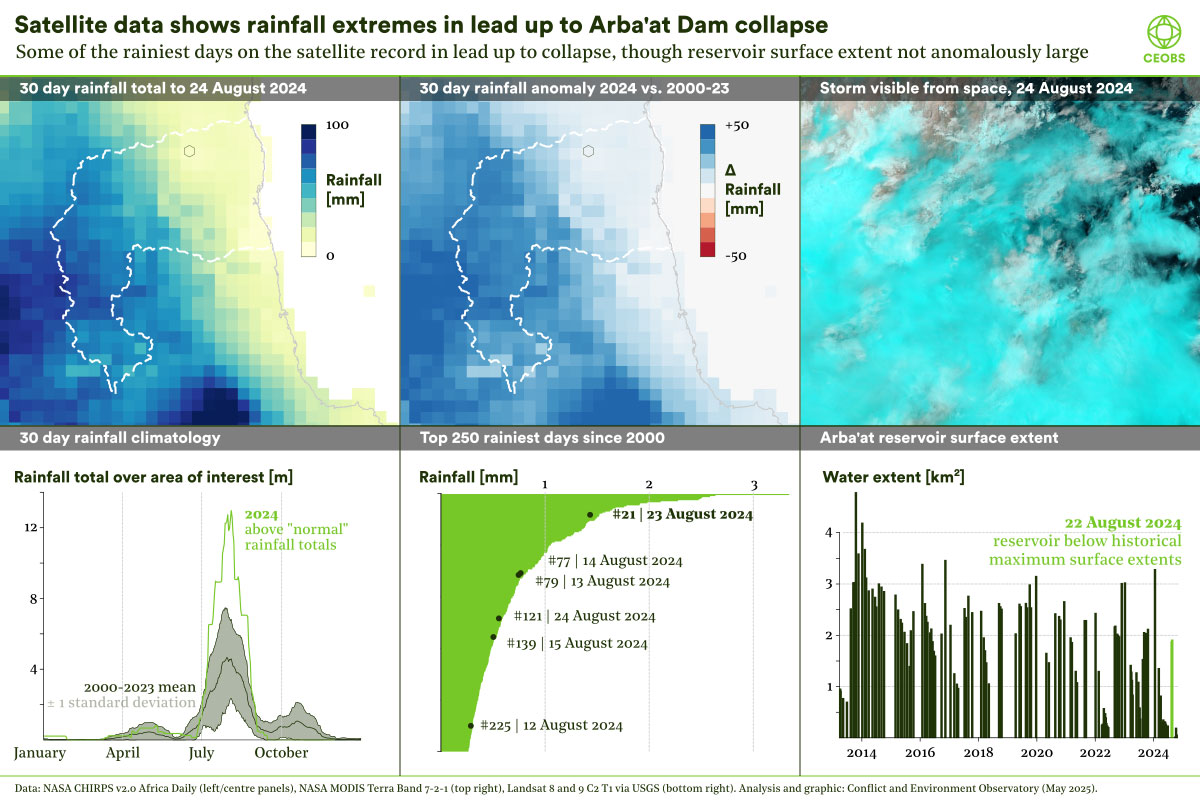

In August 2024, the collapse of Arba’at Dam near Port Sudan in Red Sea State highlighted the fragility of Sudan’s water infrastructure. Political instability and the conflict that has followed has weakened maintenance and oversight. In the case of Arba’at, analysis suggests that intense rainfall made more likely by climate change contributed to the dam’s collapse, which triggered a flood that impacted communities and agricultural areas downstream and undermined the water security of Sudan’s temporary capital Port Sudan.

Ecosystems

Protected areas

Sudan has 23 protected areas covering both terrestrial and marine habitats and which play a vital role in biodiversity conservation and sustainable resource management. Despite Sudan’s wide range of ecosystems and biodiversity, information on current species distribution and abundance remains limited. The country’s location makes it important for seasonal wildlife migration routes, connecting ecosystems across the region and linking to the Red Sea and Europe via the East African-Eurasian flyway, a critical bird migration corridor.

Sudan’s protected areas already faced growing threats from environmental degradation, infrastructure expansion, climate change, agricultural encroachment, pollution and invasive species. The conflict has exacerbated some of these pressures, while also creating new challenges, as national priorities and financial resources shift away from conservation. For example, internal displacement, resource scarcity and socioeconomic factors are altering and in some places intensifying deforestation, overfishing and overgrazing, further straining already vulnerable ecosystems.

The conflict is also placing pressure on natural resources outside of protected areas and it is crucial that protecting and restoring the fragile ecosystems that underpin livelihoods is part of any post-conflict recovery plan. The following examples illustrate some of the conflict-linked pressures that we have documented.

Natural vegetation loss in Al Gezira State

While Al Gezira State’s agricultural breadbasket is best known for its irrigation schemes, it also contains areas of natural and planted woody vegetation. Though limited, these areas play an increasingly important role in biodiversity, providing essential ecosystem services and supporting livelihoods.

We have found that factors linked to the conflict have contributed to the loss of at least 6,126 hectares of natural vegetation — equivalent to around 4,373 football pitches in one state alone; research will be needed to fully understand the extent of the impact and its consequences for biodiversity and ecosystem services. The key factors behind the loss appear to be the stationing of military forces in forested areas, and increased rates of deforestation for fuelwood and charcoal production in the absence of gas supplies.

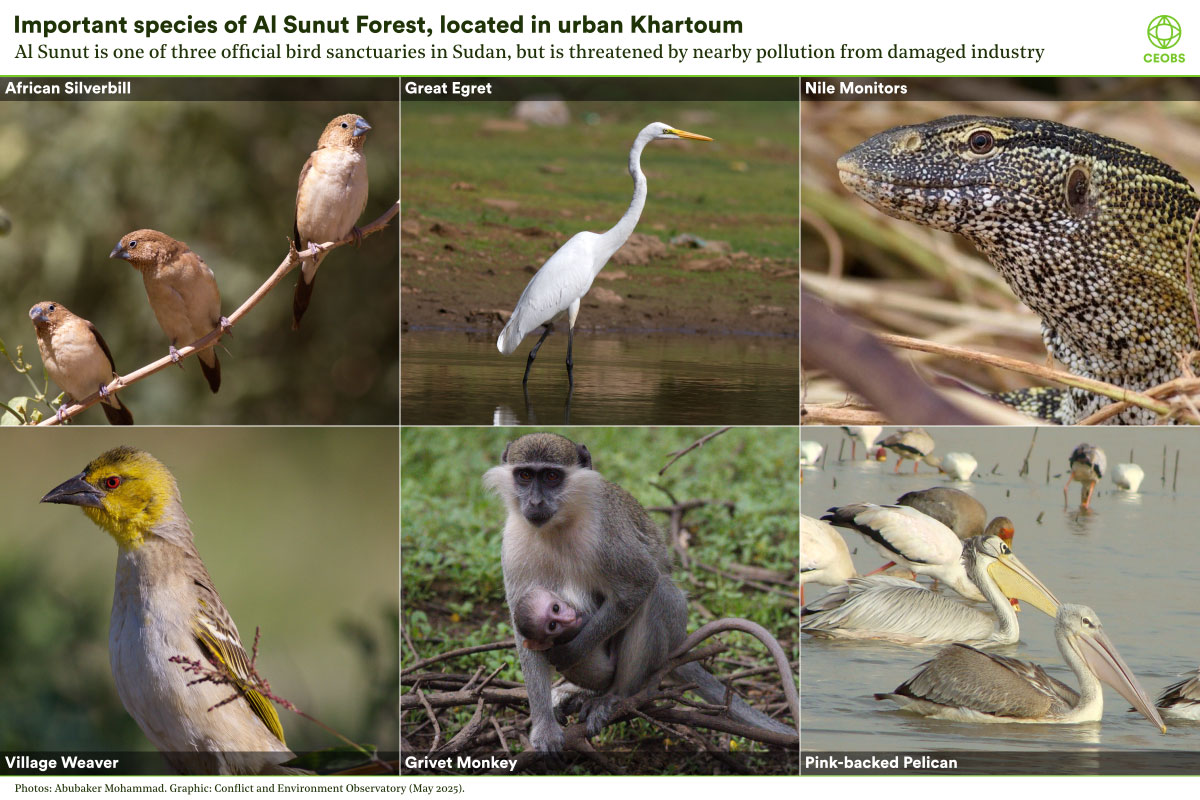

Fighting in and around Khartoum’s bird sanctuary

Al Sunut Forest in urban Khartoum is one of three officially designated bird sanctuaries in Sudan. It serves as a key hotspot for migratory birds and supports at least 110 resident and migratory bird species, along with a diverse invertebrate community.

Between April 2023 and January 2024 no significant deforestation or fire damage was observed. A more recent analysis of satellite imagery confirms that the area has remained largely unaffected.1 However, the forest is near a light industrial area, which has sustained severe damage during the conflict. Pollution from this site could have migrated into the reserve, potentially affecting its biodiversity and ecological balance. The recovery phase may also see increased pressures around solid waste dumping, an issue that has affected it historically. A comprehensive environmental assessment is needed to evaluate potential pollution risks and ensure the long-term protection of Sunut Forest and other bird sanctuaries in Sudan.

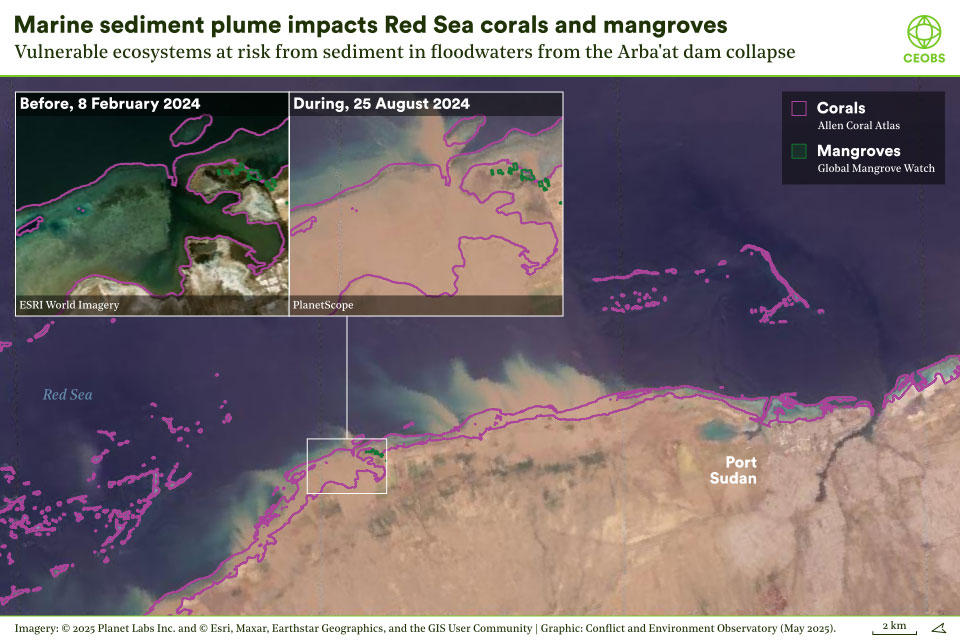

Flood pollution impacting Red Sea corals

The Red Sea enjoys optimal conditions and habitats for the growth of coral and reef ecosystems. Sudan’s Red Sea reefs are among the most pristine in the region although they are vulnerable to anthropogenic pressures and thermal stress from climate change. They support diverse marine life, including lagoonal spawning grounds for economically important fish species.

We tracked how floodwaters from the collapse of the Arba’at Dam impacted reef communities north of Port Sudan. Large volumes of sediment and debris, which may have been contaminated with toxic compounds used in artisanal gold mining, were carried downstream, smothering the coastline for days, impacting sensitive corals and marine life. Research is needed to understand the impact of the floods.

Agricultural trends

Gezira irrigation scheme – crop losses

Agriculture plays an important role in Sudan’s economy, employing around 65% of the population but the conflict has severely disrupted farming, with devastating consequences for food security and livelihoods.

The Gezira and Managil Extension in Al Gezira State, is the largest irrigated agricultural project in both Sudan and Africa, and has been particularly affected. Between 2019/20 and 2023/24, 9% of the scheme’s agricultural land was lost. This decline is linked to the conflict. Fighting in the region has displaced farming communities — between April 2023 and August 2024 we recorded 733 security incidents within the Gezira scheme; it has led to the looting of agricultural equipment, and made it increasingly difficult for farmers to access seeds and other agricultural inputs.

Research is needed to understand the impact of the war on the country’s other irrigation schemes but is particularly important for Sudan’s rainfed agriculture, which remains the primary livelihood for many Sudanese.

Exposures to hazardous pesticides

Sudan has been slow to phase out hazardous pesticides after ratifying the Stockholm Convention. Stockpiles are still thought to exist and banned chemicals such as dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), fenitrothion, and endosulfan continue to be used. Analysis of agricultural areas has revealed that pesticide storage sites have been damaged and looted increasing the risk of human exposure.

Natural resources

Gold

Sudan is rich in natural resources, with reserves of oil, gold, iron and other metals. While oil was once a major part of its economy, its significance declined after the secession of South Sudan in 2011; most of its oil reserves were in the south. By 2022, gold mining had become increasingly important for the economy, and Sudan Africa’s third-largest producer.

Both sides of the current conflict have used gold to finance the war, much of it produced informally through small-scale artisanal mining — a sector that employed over one million people in 2017. Even before the conflict, communities across Sudan were already experiencing the environmental impacts of gold mining, including land degradation, high erosion and siltation rates, and contamination from cyanide and mercury.

Sudan signed the Minamata Convention in 2014, a global treaty aimed at protecting human health and the environment from mercury pollution. In Sudan, mercury from gold extraction has been a major source of environmental contamination. However, the country has yet to ratify the convention, and with the ongoing conflict and a rise in artisanal gold mining, meaningful environmental protection remains unlikely.

Much of Sudan’s gold is smuggled to neighbouring countries such as the Central African Republic, Chad, and Egypt, with gold mined or looted by the RSF reaching the United Arab Emirates — gold revenues had long financed the RSF’s activities, as well as those of the SAF. Russia’s private military company the Africa Corps — formerly the Wagner Group — also has substantial interests in Sudan’s resources, including both gold mining and refining.

The government has lowered taxes and fees to encourage participation in the informal sector and production has surged during the war. In 2024, 65 tonnes were produced, with 53 tonnes coming from artisanal mining, an increase from 34.5 tonnes in 2022.

Research is needed to map the spatial distribution of artisanal mines in Sudan, particularly to determine whether they are located in protected or ecologically sensitive areas, and on the extent of harm being caused in the weak regulatory wartime environment.

Gum arabic

Sudan provided 80% of the global supply of gum arabic before the conflict, and the livelihoods of six million people — 15% of its population — were dependent on it. Gum arabic is the dried sap from two species of Acacia trees that grow across the south of Sudan in what is known as the Gum Arabic Belt. It is widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries as a thickener, emulsifier and stabiliser. In 2024, the global gum arabic market was valued at $526 million and, because its properties make it irreplaceable in many industries, was expected to grow further.

Beyond the economic value of their sap, the trees play a crucial role in climate resilience and environmental sustainability. They help restore degraded land, slow desertification and erosion, increase biodiversity and soil fertility, and act as a carbon sink.

The gum arabic trade could be a potential tool for environmental peacebuilding in the region but instead the industry has become a funding source for both conflict parties. This has severely impacted farmers, who have been forced to sell at reduced prices, often to smugglers, undermining their livelihoods and weakening Sudan’s position in the global market.

Climate risks and readiness

In 2022 the ND-GAIN Index — which assesses a country’s vulnerability and readiness — ranked Sudan among the 10 countries most exposed to climate change globally. Since then the war has further undermined the country’s already limited capacity to adapt and respond, with many programmes aimed at addressing climate change halted.

Beyond those directly attributable to or exacerbated by the war, Sudan continues to face severe environmental challenges, including drought, extreme rainfall variations, and desertification. In 2024, heavy rains impacted 15 states, particularly those with large internally displaced populations and relatively low conflict levels, such as River Nile, Blue Nile, and Red Sea states. This extreme weather pattern contributed to the collapse of the Arba’at Dam near Port Sudan.

Because of the growing threat posed by climate change it is crucial that the country does not overlook climate risks in recovery planning and policy-making. This includes increasing its meteorological capacity to help provide more detailed and granular information on climate risks nationwide.

Human displacement

The war has displaced nearly 30% of Sudan’s population; the majority have been displaced internally but many have fled into neighbouring countries in what is the largest displacement crisis globally. This has an environmental dimension as displaced people are typically far more exposed and vulnerable to environmental stressors such as extreme heat or flooding. During 2024, record-breaking flooding affected displaced populations in South Sudan, which included South Sudanese refugees who had returned early from Sudan because of the war, as well as new Sudanese refugees.

Similarly displacement can sometimes lead to tensions with host communities if it is not managed adequately. These tensions stem from pressures around deforestation for fuelwood or charcoal, overgrazing, water depletion, pollution from inadequate waste disposal, and land degradation. In cases such as deforestation, zones of resource exploitation can be significantly larger than population centres, whether these are camp settings or urban or peri-urban areas.

Humanitarian funding has been wholly insufficient to date, making it less likely that resources will be made available to address the environmental dimensions of displacement.

Environmental peacebuilding

From local disputes over land and water rights, to the national political economy around gold and oil exploitation, Sudan’s natural resources have the potential to contribute to conflict and must therefore be considered in any future peacebuilding efforts. At the local level, management systems have historically been used to navigate disputes over grazing land and water and supporting and enhancing these local systems is crucial, particularly in the face of our changing climate. Nationally, there are substantial vested interests at play around the revenues from oil and gold and which prevent the kind of transparent governance necessary for more equitable benefit sharing.

Even though the conflict is ongoing we have partnered with the Conflict Sensitivity Facility to examine these themes in consultation with Sudanese and international experts, along the way exploring themes around greening humanitarian assistance, building community environmental resilience, and entry points for environmental peacebuilding. The findings will feature in a forthcoming report.

Moving forward

The war in Sudan continues to receive insufficient attention from the international community, and to date consideration of its environmental dimensions has been limited. Sudanese experts and civil society should be supported to help them systematically map the war’s environmental consequences. Doing so is a prerequisite for developing initiatives to address them, whether these are measures to ensure aid programmes complement and contribute to environmental sustainability and local resilience, participatory community-led conservation initiatives, or developing the frameworks for locally relevant environmental peacebuilding that will support Sudan’s green recovery.

This post features contributions from our Sudan research team: Leon Moreland, Tasneem Sied Ahmed, Abubakr Mohammad, Klara Funke, Eoghan Darbyshire and Doug Weir. Our thanks to UNEP and to the Conflict Sensitivity Facility, and to the many Sudanese experts who have contributed to this project.