The first estimates for the financial costs of the environmental damage caused by the conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas region have been released by the World Bank.

The environmental costs of the ongoing Ukraine conflict are still to be fully quantified but an EU-UN-World Bank needs assessment has called for US$30m to fund urgent environmental recovery over the next two years. With UNEP still unable to assess or begin restoring the damage on the ground due to insecurity, this sum, which already far exceeds that for UXO management is only likely to grow.

A dirty conflict

Shortly after Zoi Environment Network and the TRWP published a first look at the environmental damage from the Ukraine conflict, the EU, UN and World Bank launched an initial post-conflict Peacebuilding and Recovery Needs Assessment. It found that although “the impact on the environment could not be quantified in this phase, it is substantial and needs attention.”

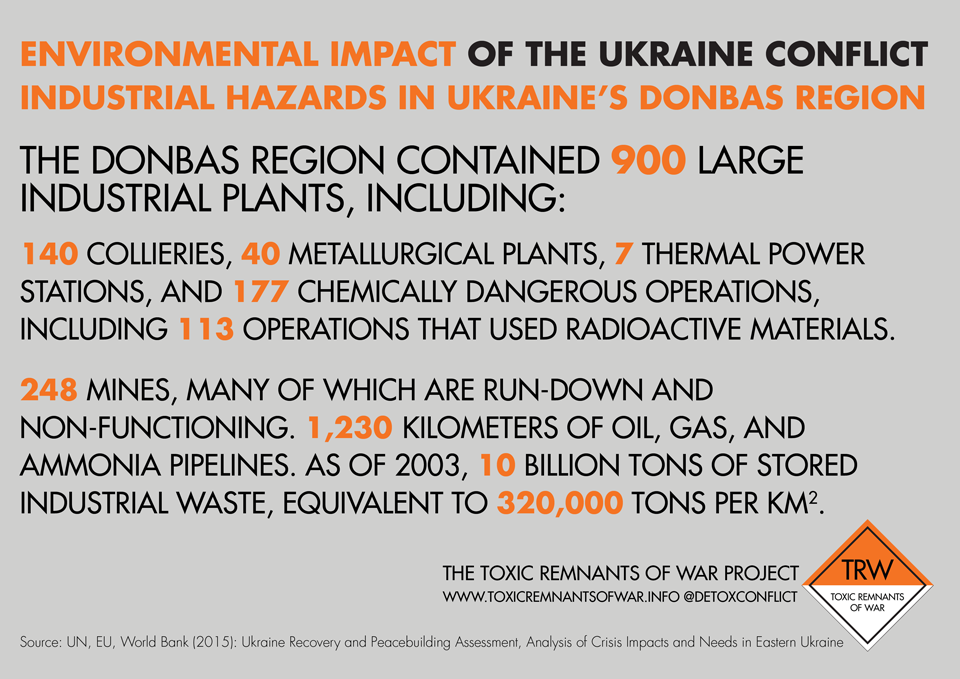

Why has it been so damaging? The Donbas region was already one of the most polluted areas in both Ukraine and the former Soviet Union, thanks to a 200 year history of coal mining and heavy engineering. Astonishingly, it was estimated in 2002 that the Donbas was home to 10bn tonnes of industrial waste, equating to some 320,000 tonnes per square kilometre.

In spite of the heavy industrialisation, the Donbas also has wild areas including forest and steppe grasslands, these natural areas have also been affected by the conflict through forest and grass fires, damage from cratering and trenches and the destruction of natural park buildings.

The list of environmental concerns includes military damage to a number of environmentally hazardous industrial sites, including industrial installations and mines. This is likely to have caused significant land, water and soil contamination that poses risks to human health, livelihoods and ecosystems. The assessment finds that 10-20 mines have been flooded, with the potential to cause “massive environmental contamination”. Damaged sites that are not currently under the control of the Ukrainian government may also pose a threat to Ukrainian-held areas.

In common with many other conflicts, the assessment finds that environmental services infrastructure has been heavily impacted by the military activities. This has resulted in improper waste disposal and limited pollution control services, and a considerable volume of conflict debris requires management. The basic process of moving household waste to storage areas has also been affected by roadblocks, while damage to sewage systems has seen releases of untreated sewage into rivers.

The Donbas’ natural resources have been extensively damaged, both directly as a result of military activity and indirectly by the inability of the authorities to sustain management interventions. The assessment finds that the incidence of fires has increased and cites four possible causes – shelling and ammunition explosions; weakened capacity of fireguards to detect and suppress the spread of fires; the build-up of dead vegetation in forests, which fuels more intense fires due to inadequate forest management interventions; and intentional arson. Important landscapes and protected areas have also been damaged by vehicle movements, the digging of fortifications and the laying of landmines.

These problems have been compounded by the collapse of environmental governance in the conflict affected areas. The assessment finds that relevant governmental agencies are now dysfunctional and that important archived information has been lost. State environmental inspections of installations were suspended while forestry staff were relocated to safe areas, resulting in a loss of management capacity. Damage to premises, vehicles and equipment is reported to have been extensive.

Loss of governmental oversight is said to have led to a rise in illegal logging and looting of timber stocks by armed groups, while criminal networks are alleged to have taken over and expanded coal mining concerns. The government is also concerned that the loss of control over its eastern border will allow a proliferation in the illegal trafficking of hazardous waste and other toxics.

Such is the damage to institutional capacity that, unlike other clusters assessed in the study, the assessment finds that merely launching initial environmental recovery operations will first require improvements in environmental governance.

Significant estimated costs

The study estimates that US$30m will be required over the next two years. Without more detailed work on the ground to quantify the true extent of the damage, this sum is based on comparative costs from other conflict areas.

Seven priority recovery areas have been identified:

Seven priority recovery areas have been identified:

- A post-conflict environmental assessment that focuses on 20 priority contaminated sites, including technical advice on emergency containment measures (US$3 million)

- A strategic environmental assessment of the DRP (US$1.5 million)

- Re-establishing an environmental monitoring program (US$2.5 million)

- Reforesting and rehabilitating protected areas – assuming that 30% of the total burned area requires urgent rehabilitation (US$17.5 million)

- Removing and disposing of debris (US$5 million)

- Strengthening environmental emergency preparedness and response capacity (US$200,000)

- Reinforcing national capacity to combat illegal natural resource exploitation and environmental crime (US$300,000)

The study envisages that the recovery plan will need to be coordinated at three levels, by the central Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources in Kiev, the Donbas regional government, and the civil society organisations and oblast authorities on the local level. While technical capacity is available on the oblast level from the State Environment Inspectorates and State Forestry Committees, the report underscored the important role that environmental NGOs will play, organisations that have already played a critical role in monitoring and reporting on damage. The importance of engagement with local communities is also highlighted in order to ensure their involvement in decision-making, and to provide job opportunities in rehabilitation projects. All of which will also require the input of international organisations for technical assistance and project management.

Conclusions

Foremost, the conflict serves to highlight the huge potential for environmental damage when fighting takes place in heavily industrialised areas, not only are new pollution problems generated but existing problems are exacerbated. Acute and long-term risks to human health and the environment can be significant and the costs of dealing with incidents enormous. The environmental damage in rebel held areas is less clear but may also prove to be significant.

Effective environmental interventions are likely to be delayed by the ongoing instability in Ukraine and this may worsen pollution risks, cause further degradation of the natural environment and encouraging more looting and smuggling. This may mean that the estimated $30m cost of the urgent recovery work will increase further however, at present it is unclear how this will be funded and it is probably unlikely that the target sum will be reached. Implementation on the ground will likely prove challenging and, given the collapse in governance, the role of civil society organisations and communities on the ground will be critical.

It is perhaps notable that the costs of environmental recovery will be far greater than that for dealing with UXO clearance and risk awareness, but no less important for the future wellbeing of the region. Yet past conflicts suggest that even with the scale of the threat the damage poses to civilian health and economic recovery, without advocacy on behalf of the environment, long-term assistance to Ukraine may fall off the political agenda in the face of other priorities.

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project