Examples of environmental harm in Ukraine | return to map

Name: Kakhovka Hydropower Plant

Location: Nova Kakhovka, Kherson Oblast

CEOBS database ID: 10177

Context

The Kakhovka Dam and the upstream Kakhovka reservoir that it formed provided drinking water to around a million people in southern Ukraine and irrigation water for around 400,000 hectares of arid cropland.1 Its hydroelectric power plant often provided balancing load for solar and wind generation in the region. The dam was completed in 1956 as the final component of a massive hydrotechnical system along the Dnipro River, and had undergone recent modernisation.

Following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, Ukraine cut the water supply to the North Crimean Canal from the Kakhovka Reservoir, arguing that as an occupying power Russia was responsible for the provision of water to the peninsula. The canal provided up to 80% of Crimea’s water – a volume difficult to replace. Water stress caused political tension in Crimea and was cited as one of the reasons for Russia’s subsequent occupation of the Kakhovka Dam.

Timeline of incidents

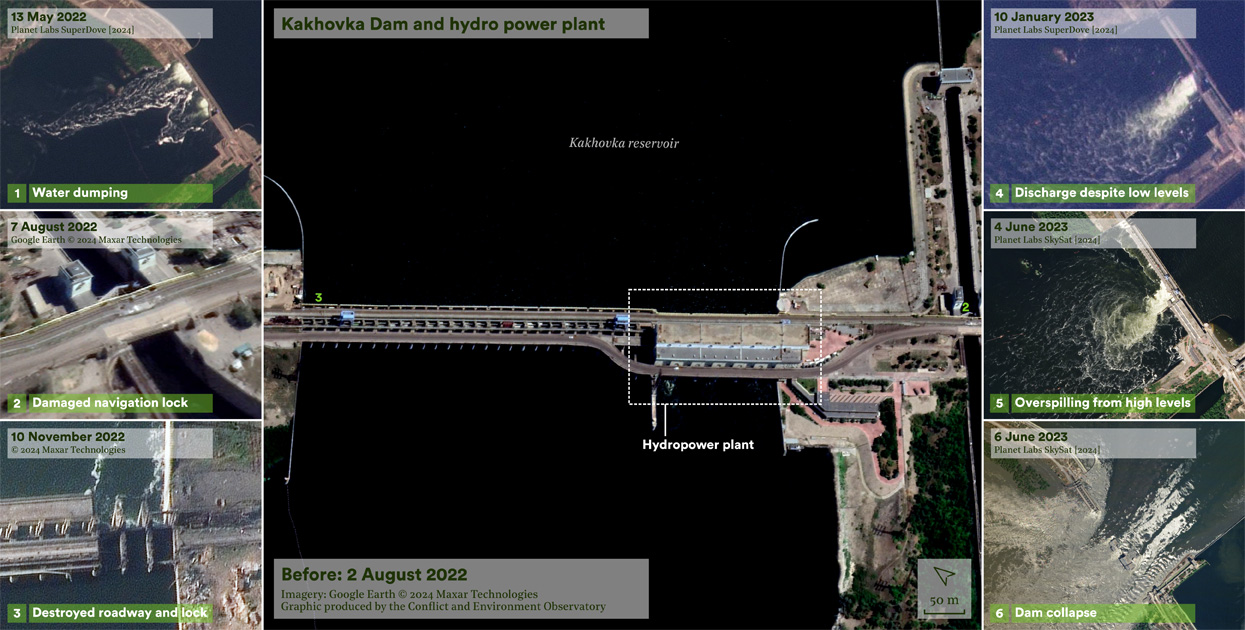

February 2022 – May 2023

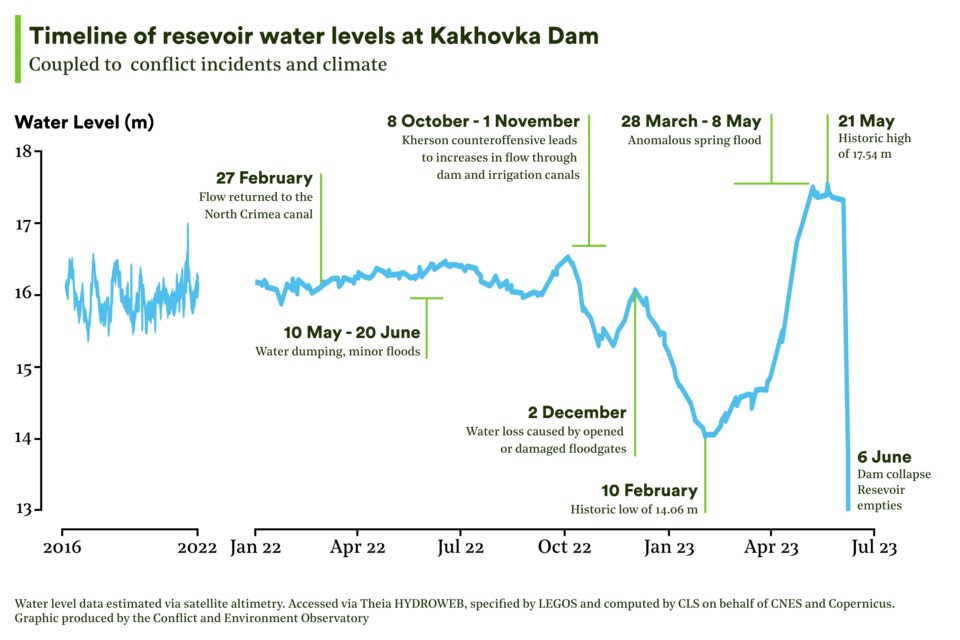

Russian forces took control over Nova Kakhovka city and the dam on the first day of the full-scale invasion. On the 27th February limited water flow returned to the North Crimean Canal after a temporary dam built by Ukraine was destroyed. By the 17th March water withdrawal had increased to 4.32 million m3 per day.

The occupation of the dam was characterised by mismanagement and neglect, which began on the 24th February with the hydroelectric plant’s disconnection from the Ukrainian power grid. Communities downstream were affected by flooding between the 6th May and 21st June when high volumes of water had to be discharged due to two inoperative hydroelectric units.2 Upstream, reservoir levels had become difficult to manage during Spring floods because procedures to balance levels throughout the Dnipro cascade were not followed.3

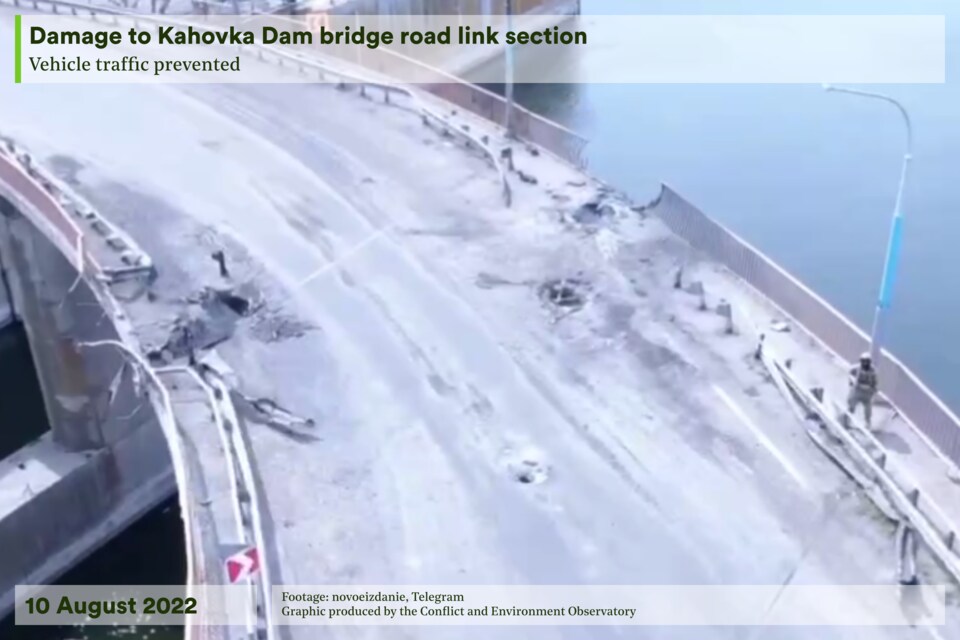

The bridge atop the Kakhovka Dam was strategically important as it was one of two crossing points over the Dnipro in the frontline areas.4 Between the 8th July 2022 and January 2023 around 35 incidents of shelling were reported,5 occasionally damaging the bridge’s road surface.

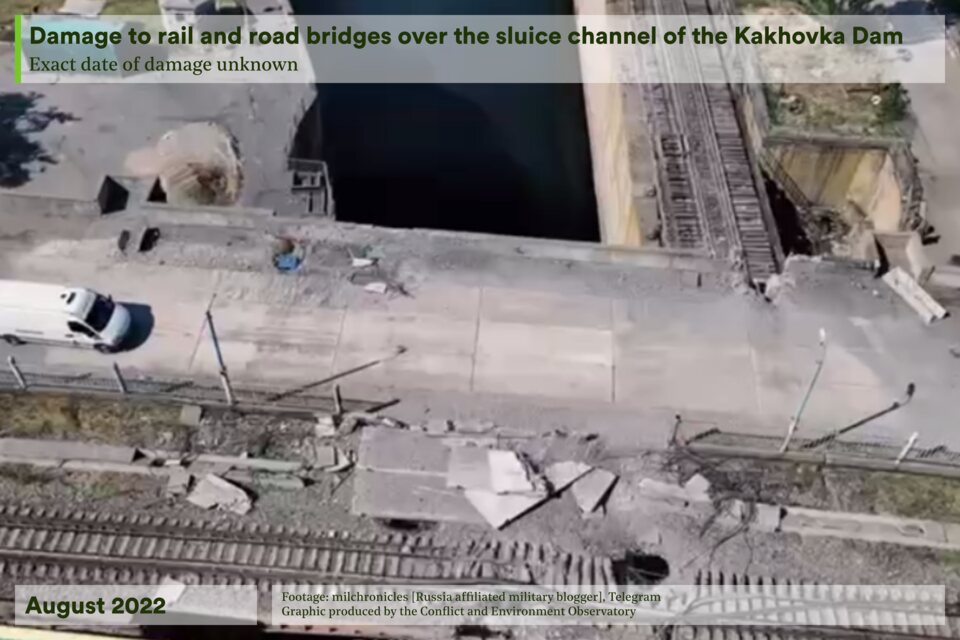

In August 2022 there were two notable missile attacks on military positions. The first damaged the railway and road bridge over the sluice channel. The second caused the sluice lock to collapse, rendering the road bridge unsafe for vehicles. Neither strike appeared to damage the dam structure. Occupying forces made temporary repairs and artillery and missile strikes continued throughout September.

With the Kherson counteroffensive gaining momentum in mid-October 2022, speculation and disinformation about a dam breach were rife.6 In response, the Russian-back authorities increased the volume of water released through the dam, and in to the North Crimean and Kakhovka Main canals.7 Satellite imagery suggests the increased discharge lasted from the 8th October to the 1st November; with the concern over water levels prompting hydrological modelling.

The situation deteriorated as military forces retreated from the right-bank of the Dnipro, destroying the northernmost section of the dam bridge on the 10th November. This severed the road link and caused a temporary discharge of water. In spite of assurances that the plant remained operational, it was suggested that occupying authorities were considering a shutdown and that explosives may have been planted at the dam.

On the 1st December the pumping station of the Kakhovka Main Channel was heavily damaged. The channel carried drinking water from the Kakhovka Reservoir to cities including Melitopol and Berdiansk, and irrigated cropland. The next day, water discharge from the Kakhovka Dam increased,8 and by the 10th February 2023, the reservoir’s water level had fallen to a historic low. Just three months later it would reach a historic high due to large Spring floods. When levels peaked on the 21st May, water could be seen spilling over the damaged section of the bridge in spite of damaged floodgates being left open.9

6th June 2023

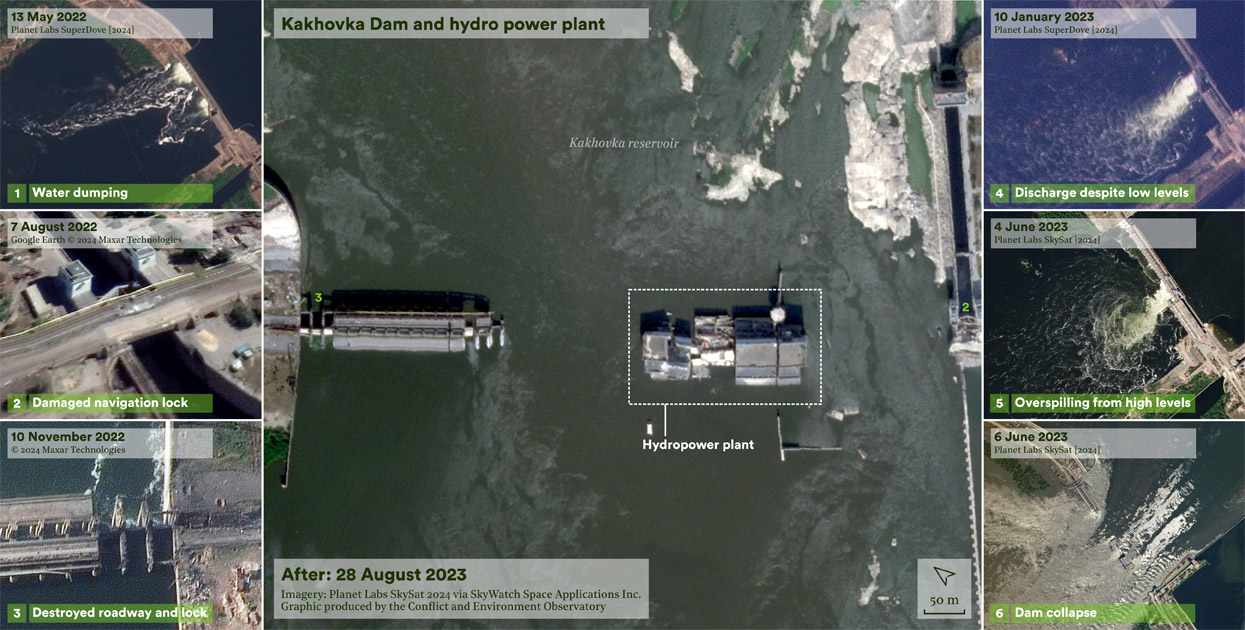

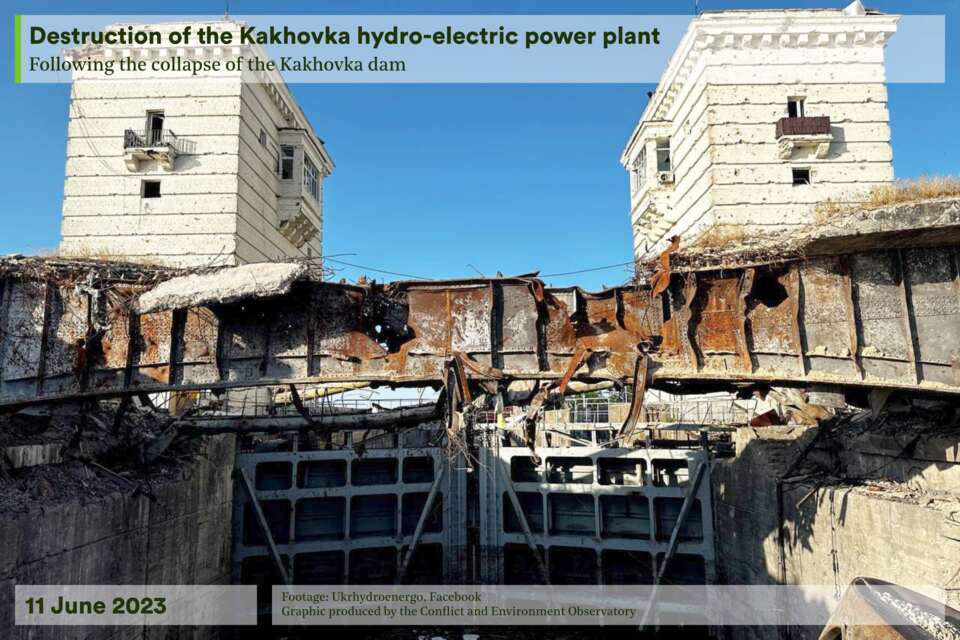

On the 6th June 2023, seismic monitoring identified two large explosions in the vicinity of the dam around 02:50 local time. These corresponded with social media reports of its collapse. The explosions destroyed the hydroelectric plant’s engine room and affected 11 of the dam’s 28 sections; engineering and explosive experts suggested an internal explosion was the most likely cause. Poor maintenance, which included allowing the water to reach abnormally high levels, may have caused some deformation of the dam in the months prior to its collapse.

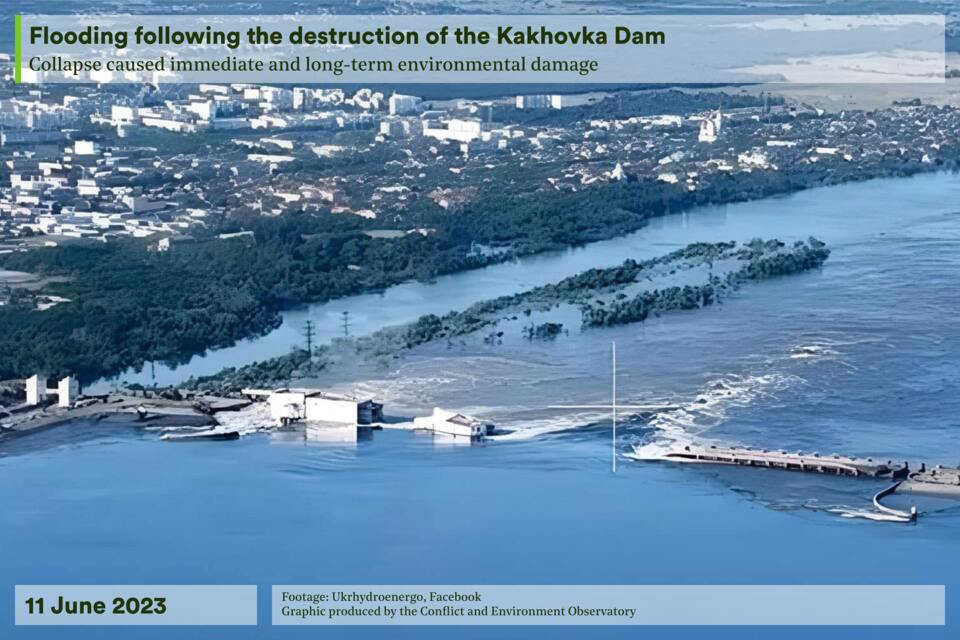

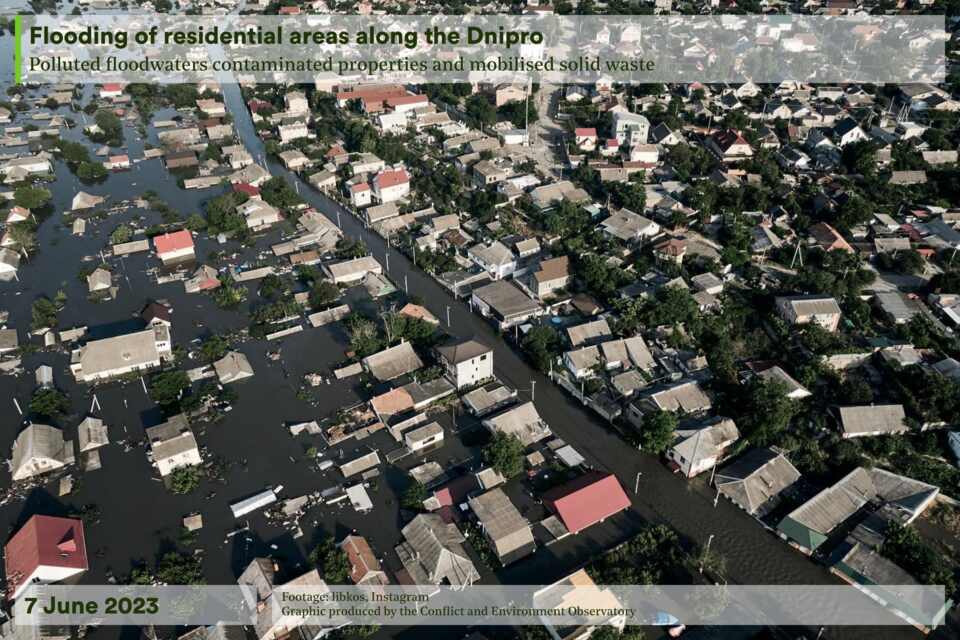

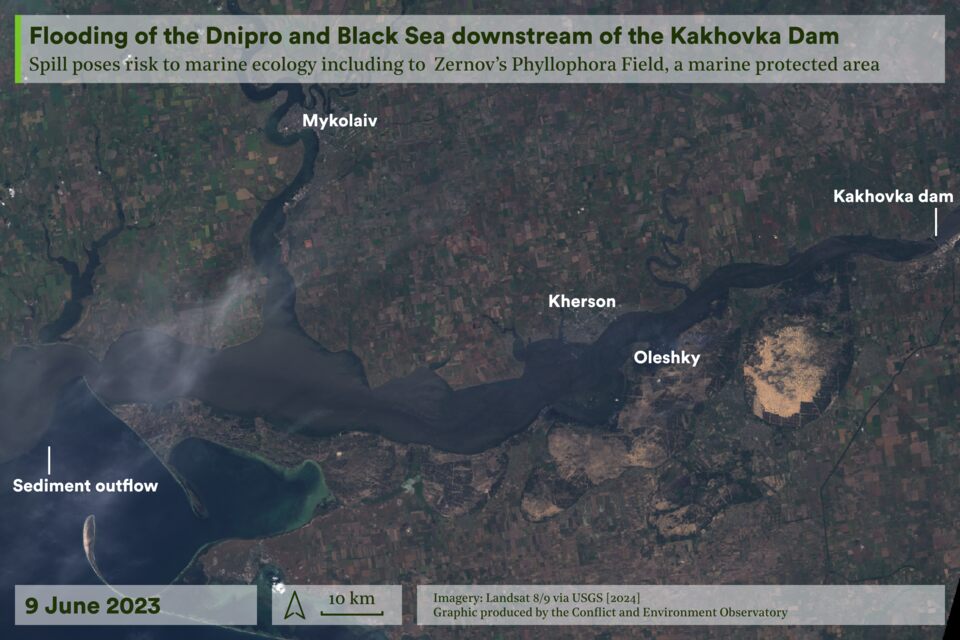

The impacts from the dam collapse were profound. Around 620 km2 of land was flooded between the 6th and 9th June, including 333,000 hectares of protected areas, 10,000 hectares of agricultural land and more than 11,000 hectares of forests. More than 14.7 km3 of water was released, affecting 80 settlements along the Dnipro and its tributaries and directly impacting 100,000 people.10 Settlements on the occupied left bank were most severely affected with Oleshky and Hola Prystan remaining flooded for more than a month.

Damage assessment

The destruction to the dam appears near total. The machine room is reportedly unrepairable, while the damage to the earthworks can only be properly assessed once Ukrainian engineers have access.

Environmental harm assessment

Harm downstream

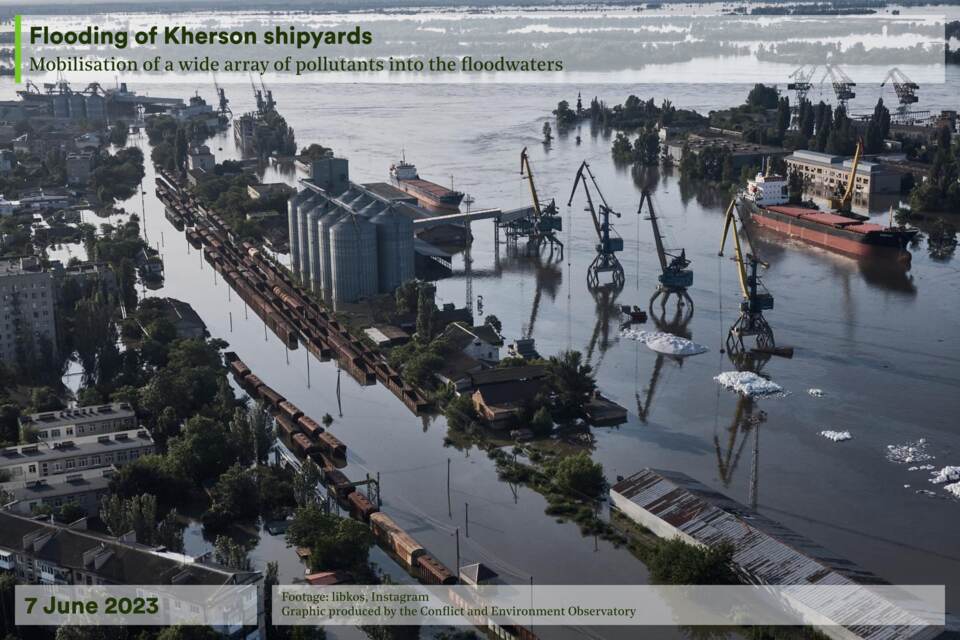

More than 1,000 potential pollution sources were inundated by floodwaters, including fuel storage and transit infrastructure – a large oil spill occurred in Komyshany when an oil pipeline was damaged. Numerous chemical, industrial and agro-industrial sites were also affected, such as the major shipbuilding and port complex in Kherson.

Waste was mobilised from landfills, sewage facilities and properties. In Oleshky alone, flooding affected cemeteries, tailings piles and 37,000 homes.11 Minefields and at least 47 military positions were flooded, dispersing military pollutants and transporting unexploded ordnance. The dam itself was also a pollution source, discharging around 150 of the 450 tonnes of fuel oil it was thought to have held.

Severe flooding affected the Inhulets and Viryovchyna tributaries, causing pollution and transporting Dnipro contaminants far upstream to communities including Afanasiivska and Snihurivska. The huge water volumes caused flooding and physical changes to the ecologically sensitive wetlands in the lower Dnipro. In the Black Sea, the rapid outflow of polluted freshwater impacted coastal and marine ecosystems. The Dnipro can no longer be used as a deep-water cargo route to the Black Sea, with navigation south of Zaporizhia now impossible.

Water samples taken in Dnipro-Buh estuary, Dnipro River and Black Sea near Ochakiv found increased concentrations of industrial pollutants, including heavy metals arsenic and cadmium, hydrocarbons and PCBs, as well as pollutants from sewage. However, sampling was restricted due to the proximity of the active frontline.

Harm upstream

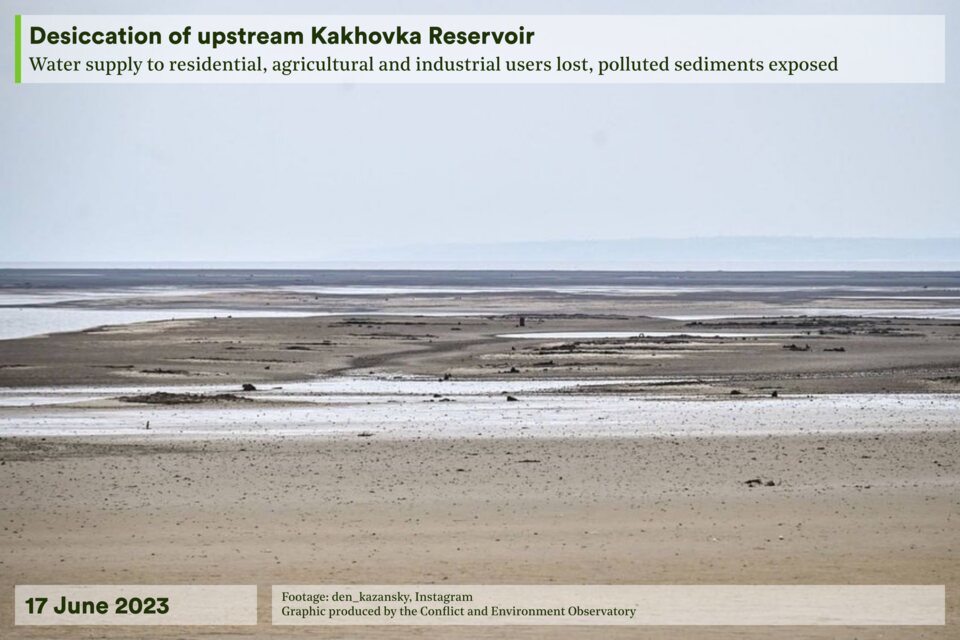

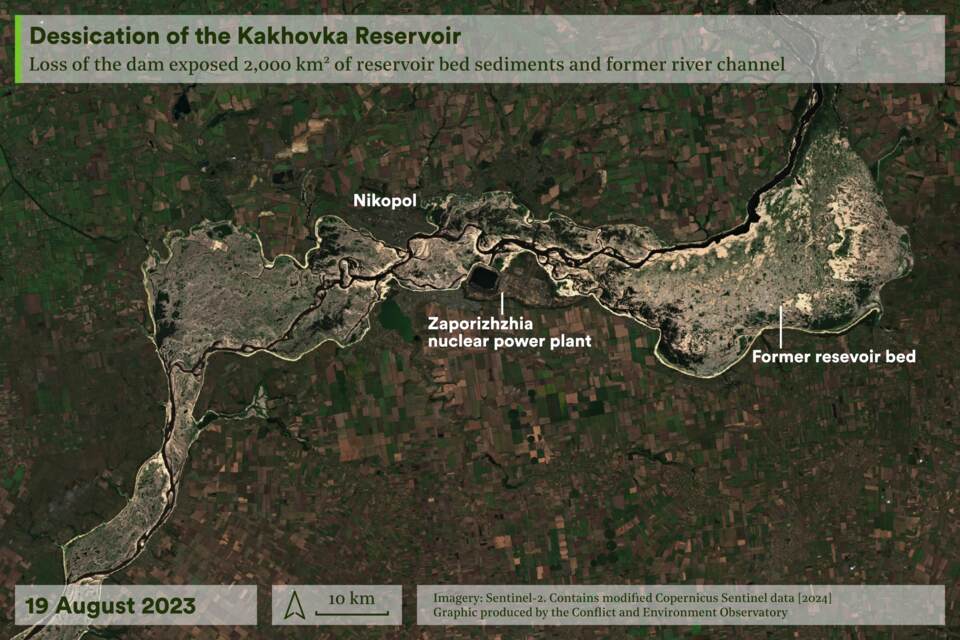

The loss of the Kakhovka Reservoir had immediate and longer-term consequences for ecosystems, livelihoods and regional water supplies. The reservoir fed more than 30 irrigation systems that could support up to 584,000 hectares and supplied water to numerous domestic, industrial and energy users. Fears over the availability of cooling water for the Zaporizhia nuclear power plant were urgently addressed by the construction of new wells.

Agriculture rapidly began to be affected, impacting livelihoods. The reservoir had been a source of drinking water for one million people; emergency water trucking, well drilling and costly pipeline construction was launched to restore supplies. The long-term impacts of changes to the morphology of the river channel and the downstream impact of sediment mobilisation are yet to be assessed.

Harm across the Dnipro basin

Ecologically important areas were flooded or desiccated. These included an internationally important Ramsar wetland, Emerald Network sites and important bird nesting areas. Regional ecosystems had developed around and become dependent on the reservoir since its construction. Ecological succession processes will take decades, and likely take a different form given the changing climate and Dnipro flow regime, as well as major land use changes.

Environmental harm had already occurred before the dam collapse, which may have compounded its impacts. Fluctuating reservoir levels had led to the loss of aquatic fauna and spawning grounds.

Longer-term implications

The region’s infrastructure evolved around the reservoir for 70 years. Systems irrigating the dry steppe boosted agricultural productivity, and economic and population growth; prior to 2022, work had begun to make these systems more efficient and sustainable. Water shortages are expected to impact small-scale farmers and households most severely.

Many water-dependent factories in what was a large metallurgical, engineering, energy and chemical cluster, are now dormant. Their historic discharges have raised concerns about levels of heavy metals and industrial pollutants in the sediments of the former lakebed. The reservoir ecosystems provided dilution and biological attenuation of wastewater and surface runoff.

Short and medium-term water supply solutions can come at a cost, including increased groundwater drawdown and decreasing recharge, both of which are likely to reduce water quality. Regionally, groundwater is scarce and unlikely to be able to fully replace lost irrigation. Dryland farming may encroach upon larger areas of land to compensate for drastically decreased yields. Disputes have emerged over proposed uses for the former lakebed that would be environmentally harmful.12

Dis/mis-information watch

In October 2022, Russia launched a misinformation campaign that sought to blame Ukraine for any potential dam disaster. After June 2023’s dam collapse, Russia accused Ukraine of destroying it, in spite of the facility being under the control of Russian forces at the time.

External resources

Rapid Environmental Assessment of Kakhovka Dam Breach | UNEP

A rapid assessment of the immediate environmental impacts of the destruction of the Nova Kakhovka Dam, Ukraine | UKCEH and HRW

Return to the country map here.

- Dnipro water supplied the Dnipro-Kryvyi Rih Canal; the North Crimean Canal transported water to Crimea; and the Kakhovka Magistral Canal provided water to the arid Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions.

- The Russian management suggested that hydropower unit no. 3 was out of order from March 2022.

- These are based on needs and the hydrometeorological situation across the Dnipro cascade, as agreed by the State Water Resources Agency of Ukraine.

- The second crossing point is the Antonivsky bridge around 50 km downstream, which was also heavily impacted by fighting and was eventually destroyed. A third bridge at Darivsky crossing the River Inhulets, a Dnipro tributary, was also destroyed.

- Based on CEOBS’ detailed analysis and database of environmentally relevant incidents from the conflict in Ukraine.

- Russian and Ukrainian officials exchanged accusations of intent to destroy it, the Russian government took the issue to the UN Security Council, and occupation authorities in Kherson used the threat as a pretext to displace occupied peoples from the right to left bank.

- The North Crimean Canal is on the reservoir’s left bank, adjacent to the dam. The Kakhovka Main Channel is also on the left bank, but around 20 km away from the dam.

- Satellite imagery shows that Russian forces used two gantry cranes to open additional floodgates.

- Comparing Planet imagery in November 2022 shows water accumulation and release through different parts of the dam. Meanwhile, since 2023, some of the HPP floodgates continuously dumped massive volumes of water, and only one group of them appeared to remain operational.

- 17 people died by drowning and injuries on the government-controlled territories when Russian forces targeted evacuation vessels. On the left bank, the human toll may have been in the hundreds, as the Russian-backed authorities failed to organise proper evacuations and actively covered up the real number of victims.

- During the immediate flood response in Kherson, the State Emergency Service cleared about 1,400 tonnes of debris daily. Waste and debris from flooded homes must be treated as potentially polluted and may contain asbestos and other hazardous materials. Local capacities to manage waste had already been strained because of the fighting.

- For example, manganese mining in Nikopol or industrial agriculture.