Examples of environmental harm in Ukraine | return to map

Name: Sievierodonetsk Azot Association

Location: Sievierodonetsk , Luhansk Oblast

CEOBS database ID: 10162

Context

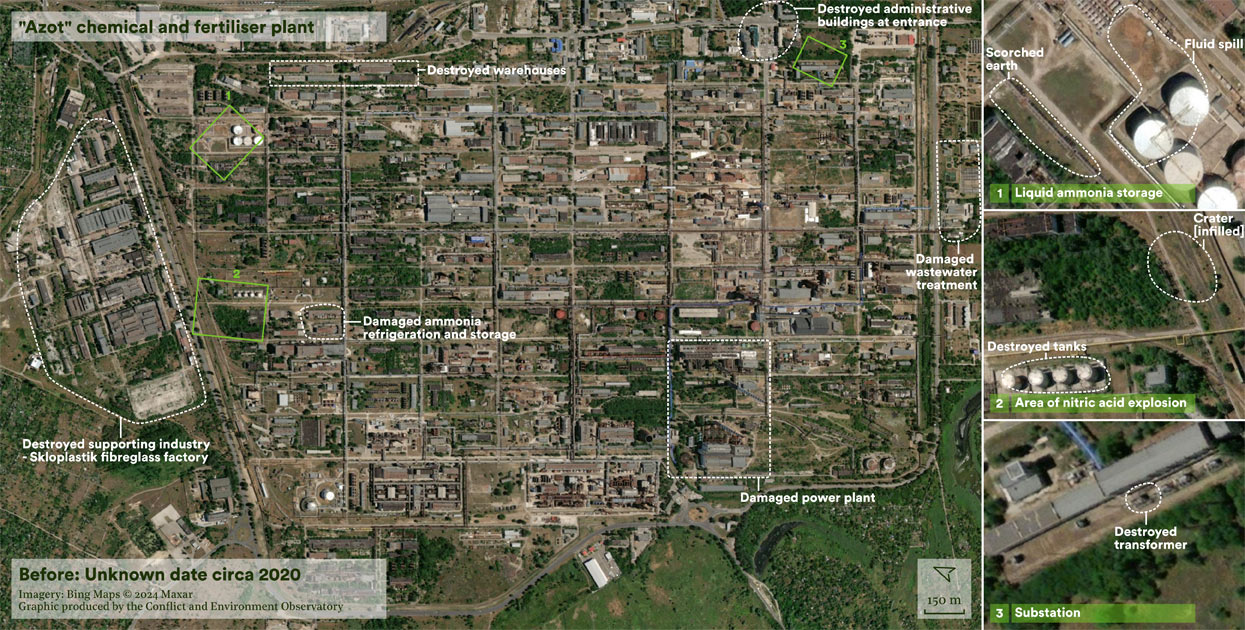

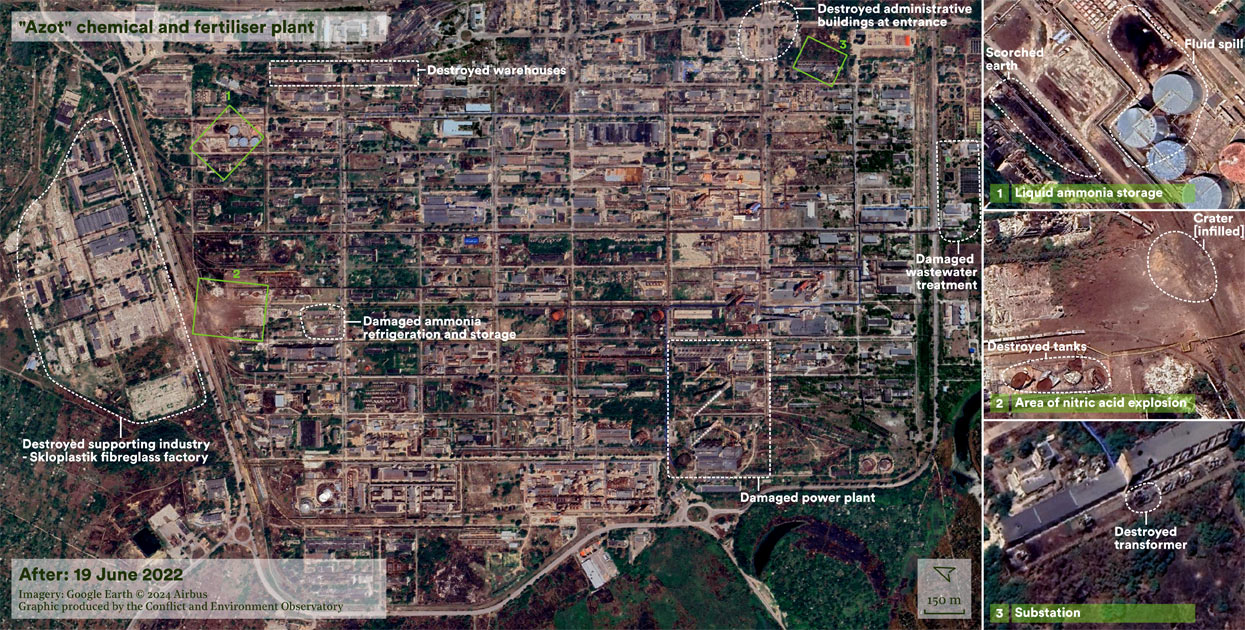

Azot Association, or “Azot”, is a large chemical manufacturing complex in the west of the city of Sievierodonetsk, with a footprint of 6.3 km2. Prior to February 2022, it employed around 5,000 people and was one of the largest producers of ammonia and mineral fertilisers in Europe.

Timeline of key incidents

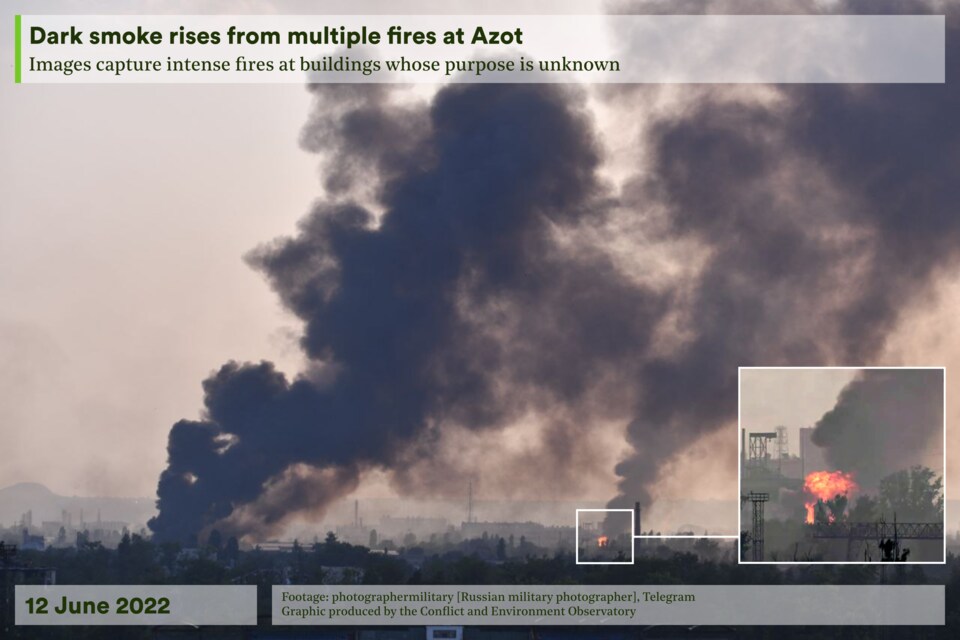

Azot was the site of a significant military battle during May and June 2022, causing widespread physical damage, and of a propaganda battle throughout the year, in which disinformation and fake news played on both real and imagined environmental threats. Whilst shelling or damage was reported by the Ukrainian authorities on multiple occasions in March, and near-daily in May and June, little documentary footage was openly available in comparison to other frontline locations.

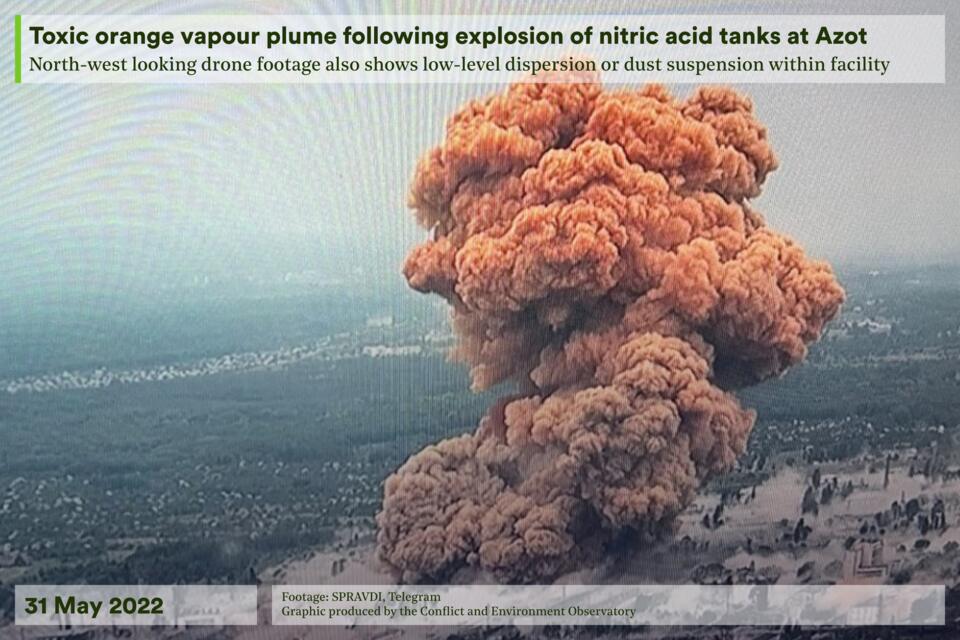

31st May 2022

The explosion of products stored in railway carriages on the 31st May – reportedly involving nitric acid – produced a large, high-altitude and characteristically reddish-brown plume of nitrogen oxides. These are highly toxic if inhaled and the plume presented a significant public health emergency for nearby troops and the few thousand civilians remaining nearby.1 The huge explosion left a crater 60 m wide and several metres deep, destroying nearby storage tanks and most buildings within a 300 m radius. Social media reports of another similar explosion on the 12th September were not substantiated with any footage but are plausible.2

Damage assessment

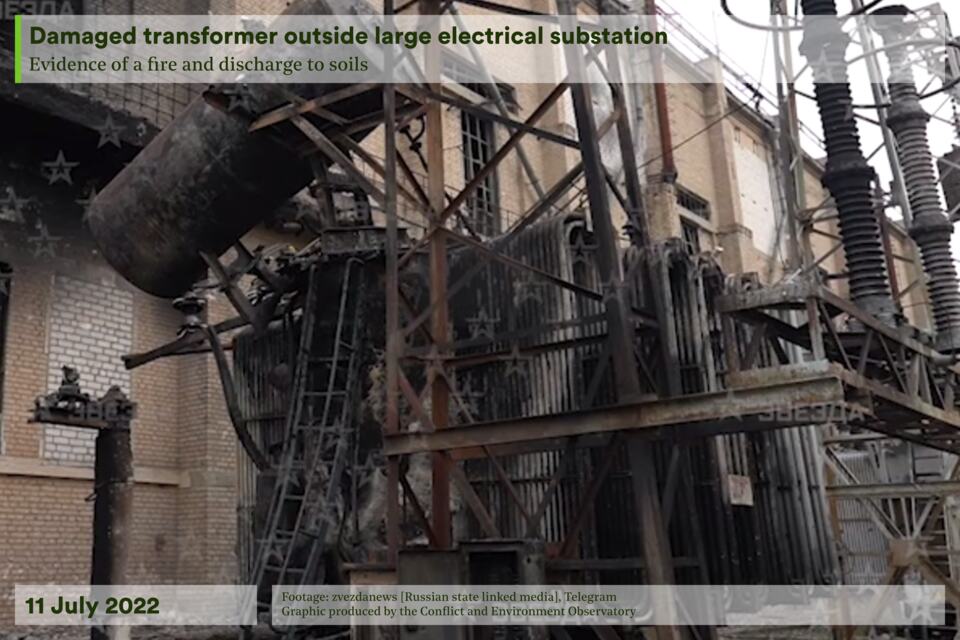

The Azot plant’s operators claim that almost all the site’s infrastructure has been damaged. This includes environmentally sensitive objects, such as the plant’s ammonia and nitric acid workshops; methanol and urea-ammonia-nitrate storage, the power station and substations; water supply systems; and the wastewater treatment system. This damage has been confirmed by analysis of satellite imagery and drone footage.

Combat has caused significant direct physical damage across the facility; at least 26% of built structures had been destroyed by the end of September 2023, based on an analysis of Synthetic Aperture Radar.3

Environmental harm assessment

The damaged infrastructure has generated many sources of contamination, including: deposition from the large explosion, and leaks of unidentified liquids from damaged storage tanks; widespread damage to pipelines; cratering and disturbance to ash and sludge deposits; and the large volume of debris from damaged or destroyed buildings.

Contaminants will have been released directly onto soils or indirectly through infiltration from surface waters, themselves polluted from run-off across the contaminated site. There have been a number of significant emissions of pollutants into the air. Most obviously from the nitric acid explosion, but there will also have been resuspension of contaminated dusts, and pollution from the many fires arising from shelling; for example a fire was reported at a warehouse that may have been storing chemical waste on the 10th June 2022. Pollution from Azot will also be compounded by the diverse contaminants from other industries within Sievierodonetsk.4

Much of the environmental risk depended on the strategies employed to manage the contents of this large industrial site before and during the fighting. Four days into the war, its operators claimed all chemicals had been relocated offsite. This seems implausible given its scale – as demonstrated by the large nitric acid explosion – and because stored materials were still visible on drone footage. There are also likely residuals and contaminants in equipment as well as non industry-specific pollutants such as fuel or lubricants.

Ground surveys and sampling are needed to fully understand the environmental risk, ideally by those familiar with the site and with access to baseline data, including its geology and existing ground contamination, to model migration and chemical changes. This includes assessing the risk to the Siverskyi Donets River, which Azot sits adjacent to and above. Along with any discharge pathways, the river water quality requires monitoring. The local wastewater treatment plant was also damaged to the extent that it could no longer supply the needs of Sievierodonetsk. This may have led to flooding downstream, while the plant’s highly contaminated sludge settlement ponds may constitute a threat if damaged.

Longer-term implications

Longer-term, Azot will remain an environmental liability due to its decades of operation,5 and the wartime damage, requiring constant monitoring and safety interventions. Reopening the plant may be feasible and this may help address some of the environmental risks, although there may be political complications.6 However, it is reported that useful materials have been transported to a similar facility in Russia; this may account for the repairs to rail infrastructure and the movement of carriages visible on satellite imagery.

Dis/mis-information watch

Misinformation plagued reporting on Azot, particularly from pro-Russian actors, and represents one of the more significant examples of the weaponization of environmental information during the war. The pro-Russian narrative alleged that the Ukrainian armed forces were mining chemical warehouses with the intention to cause an environmental emergency, and to then blame pro-Russian forces. These allegations began in February 2022, were repeated many times thereafter and were widely proliferated across the pro-Russian media ecosystem.

It was alleged that Ukraine planned to use civilians as human shields to prevent damage to the plant and subsequent chemical releases.7 Forces of the self-styled “Luhansk People’s Republic” and pro-Russian political leaders claimed they had avoided attacking the site out of fears of triggering an environmental emergency, yet appeared to shell it afterwards. Others sought to rebut these claims by arguing that no chemical hazards remained at the plant.

Following Russia’s capture of the plant, there have been disputable Russian claims about UN-related weapons stashes, and ongoing promises to restart the plant. Arguments about events and responsible parties also played out in the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

Return to the country map here.

- Especially given the difficulties for an emergency response – a comparable incident occurred in Catalonia in 2015, triggering an emergency response and detailed post-disaster assessment.

- Although a crater of a similar size is not clearly visible on satellite imagery – the explosion may have been at the same location, or smaller elsewhere.

- This was calculated by analysing the intersection between built structure polygons, obtained from a combination of OpenStreetMap and Microsoft Buildings, and damage mapping produced by Jamon Van Den Hoek (Oregon State University) and Corey Scher (City University of New York), derived from Sentinel-1 data. Visual inspection of very high resolution satellite imagery shows that this method underestimates damage.

- These include production facilities for fibreglass, heat and power equipment, building materials, reinforced concrete products, silicate bricks and ceramics.

- The Azot plant had a long history of environmental harm. It had previously been the 15th most water-polluting enterprise in the country, a significant source of air pollution locally and globally, and had a questionable approach to environmental assessments.

- Azot is owned by Dmytro Firtash.

- Hundreds of civilians sheltered in Azot from March 2022 until the end of June.