The widespread use of primitive and indiscriminate barrel bombs in Syria has caused massive civilian casualties, but do their explosive fills also present health risks to civilians?

The TRWP was recently asked to help identify a substance associated with partially detonated barrel bombs in Syria. Syria’s White Helmets, the volunteers who daily risk their lives in the aftermath of attacks, were understandably worried about the potential use of chemical agents by the Assad regime. While the irritant fumes and pink powdery residue appeared to be from TNT and not a chemical weapon, the health risks from exposure to this common explosive are increasingly well understood and should be taken into account when examining the civilian impact of the use of explosive weapons in populated areas.

Barrel bombs in Syria

By December 2013, it was estimated that barrel bombs had killed 20,000 and injured thousands more. The indiscriminate improvised air dropped devices have been a hallmark of the Syrian conflict and widely used in towns and cities, as of June 2014 it was estimated that between 5-6000 barrel bombs had been dropped by regime aircraft. In February 2014 the UN Security Council called for a halt to the tactic but a report from Human Rights Watch subsequently found that their use had accelerated in the months that followed.

Barrel bombs are cheap to produce from locally available materials and were first documented in the conflict in Darfur; in 2014 the Iraqi Army was reported to have used them in Fallujah. Over the last few years, the devices used in the Syrian conflict have grown larger and more sophisticated, they are typically dropped from helicopters at altitude and examples weighing 2000lbs have been reported. The weapons have been found to contain a range of materials including explosives, metal fragments and, most recently, chlorine gas.

TNT toxicity and behaviour

It is thought that the majority of barrel bombs employ the widely used secondary explosive TNT (2,4,6-trinitrotoluene). Developed in the 1900s, TNT was initially viewed as so insensitive as to be useless as an explosive but subsequently became a standard component of many of the explosive compositions used by militaries worldwide. The traditional process used to manufacture TNT is highly polluting. It uses toluene as a feedstock and requires large volumes of water. For every pound of TNT produced, 1.5 gallons of hazardous ‘red water’ is generated. Managing the toxic waste water from production sites has proved highly problematic in the US and elsewhere and a number of countries have ceased production as a result.

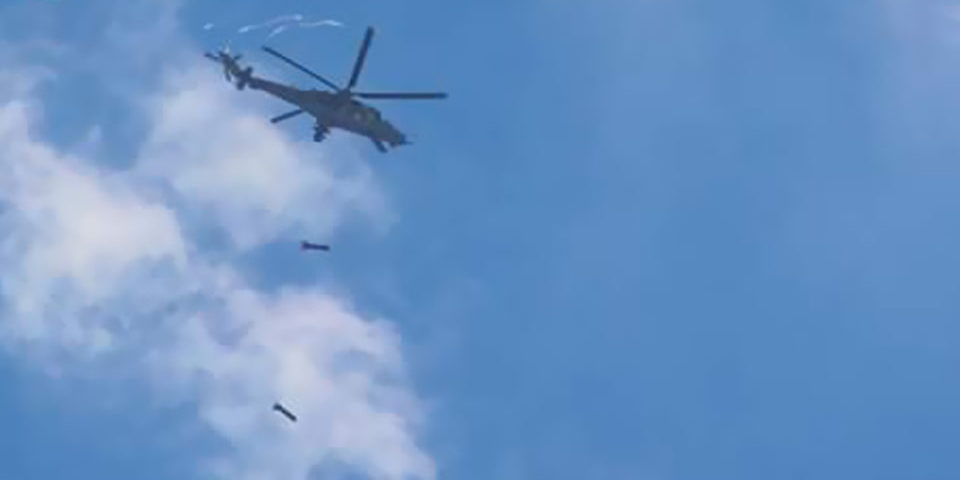

TNT dispersed from a barrel bomb dropped in Hreitan Syria, March 15th, 2015. Source: White Helmets.

The photos received by the TRWP showed a pink substance covering the craters in the vicinity of the damaged barrel bombs. Volunteers from the White Helmets had also reported the venting of an irritant gas. The colour of the staining was important in identifying the presence of TNT but it is also a clue to the complexity involved in efforts to determine the environmental fate and health risks from TNT.

The first studies into the health risks from TNT were undertaken on munitions factory workers in the 1940s after 17,000 cases of TNT poisoning resulted in more than 475 fatalities during WWI. Prolonged exposure is now associated with skin conditions, blood and liver damage. Efforts to determine the mechanism of harm have required a thorough investigation into how TNT breaks down, both in the body and in the environment. The pink staining seen around the Syrian bomb crater illustrates one of these processes – photolysis. Sunlight can cause rapid colour changes to TNT and this can be accelerated in the presence of calcium rich soils.

How TNT behaves in the environment depends on three factors, those relating to the physiochemical properties of both TNT and its breakdown products, those that relate to the environment in which it is present, such as soil pH, and biological factors such as the presence and activities of microorganisms in the soil. These all control how TNT degrades, which substances it degrades into, the length of time they remain in the soil and how mobile they are. It is a surprisingly complex story. The picture within the body is similar, with TNT thought to be metabolised by the liver into four substances, all of which have been found to bind to blood cells.

In recent years, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that TNT and its metabolites in mammals are genotoxic i.e. they can damage DNA. This has been demonstrated using a number of different makers for damage. In 2008, this led officials for the State of California to conclude that there is now sufficient evidence to show that TNT is a carcinogen. The US Environmental Protection Agency, which has not updated its TNT cancer review since the early 1990s, nevertheless lists it as a pollutant of high concern, and published an updated fact sheet in early 2014, together with drinking water guidelines.

Exposure risks from barrel bomb use

TNT’s toxic effects are relatively well documented, exposures have been found to cause liver damage, cyanosis, sneezing, cough, sore throat, peripheral neuritis, muscular pain, kidney damage, cataracts, sensitisation dermatitis, leucocytosis and leucopenia (effects on white blood cell count), and aplastic anemia (damage to blood cell production in the bone marrow). However, cancer risks from long term exposure to TNT have not been well studied in humans and much of what is known comes from animal and tissue studies.

Damage sites from barrel bomb use in rebel held areas of Aleppo before and after UN Security Council Resolution 2139. Source: Human Rights Watch.

Studies into TNT residues from conventionally produced munitions that function properly under ideal conditions have been conducted. Data from ranges appears to show that high order detonations leave relatively low levels of residue but there is considerable variation between munition types and studies. It is clear from the footage of barrel bomb use that many do not function as intended and, as a result of their primitive designs, it seems likely that even where they do, residues may be considerably higher than those expected from more traditional weapons.

The use of the weapons in populated areas also present a different exposure and risk dynamic to the use of weapons on firing ranges, many of which may be inaccessible to the public. In such areas, inhalational exposures to pulverised building materials mixed with residues from TNT and other energetic materials may be widespread. A further concern is the production process the Assad regime is using for TNT production. Improper controls over production processes will likely result in higher levels of contamination from chemical precursors such as 2,4- and 2,6-DNT in the final product, both of which were recognised as being more carcinogenic in humans than TNT in a 1996 review by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).

Determining the extent to which TNT and it degradation products are distributed and persist in the environment in Syria’s towns and cities is key to understanding exposure risks. The security situation means that such studies are unlikely to happen any time soon. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that the presence of these munitions residues poses a health risk to those who remain, and particularly those who volunteer to help rescue the casualties of Assad’s bombing and who may face repeated exposures over prolonged periods. While TNT is less environmentally persistent than RDX, it is one of a number of environmental contaminants that should be taken into account in efforts to quantify the long-term public health impact of the use of explosive force in populated areas. TNT is also just one of many threats from toxic remnants of war that have been created by the conflict in Syria.

Our thanks to Ira May and Jake Irwin for their swift technical advice on the images in question.

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project.