This blog examines the different opportunities for wildlife conservation that were explored ‘before, during and after’ South Sudan’s most recent civil war.

The International Law Commission’s draft principles on the Protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts use a temporal framing of ‘before, during and after’ conflict. Drawing on his experience working in South Sudan, Adrian Garside discusses the importance of this temporal framing for the planning and management of wildlife conservation programmes in conflict-affected areas.

Introduction

South Sudan, and southern Sudan prior to its independence, has been in a cycle of conflicts for more than 65 years, spanning three civil wars with numerous armed conflicts in between. Gains made in the wildlife sector, and other areas of development, during periods of stability have been quickly lost in the recurring wars. At the time of writing, the peace agreement to conclude the third of these civil wars has been signed and the Government of National Unity has formed. However, on the ground fighting continues with the remaining armed elements who do not support the deal, while armed community defence groups counter the lack of human security. Competition over natural resources has escalated to armed warfare, and the government is powerless to do much, being both predator and prey. These realities make it impossible to draw a clear dividing line between the start and end of this war, and the notion of post-conflict peacebuilding as a phase presents a very ambiguous entry point.

This is where the International Law Commission’s (ILC) temporal framing is useful: it recognises that war and armed conflict continue to have a huge impact on the environment, outside of the brackets we place around the period ‘during war’. This blog examines the different opportunities for wildlife conservation that were explored ‘before, during and after’ South Sudan’s most recent civil war.

To explain this, it is necessary to place the temporal frame within the dimensions of space and scale. This is nothing new: there are numerous concepts for working in a multi-dimensional conflict environment or in contested areas, though usually this concerns humanitarian operations. I hesitate to use the word ‘stabilisation’ because the ambiguous term has been contested, misunderstood, and often applied incorrectly. However, as an approach the term offers ways of working in conflict situations and importantly, it is political.

Wildlife conservation involves people, land and natural resources and therefore is also political, and even more so during war, although in certain circumstances, it can also provide a neutral entry point. The case study for this blog is the area of Western Equatoria, though placed within the national context. This area includes the western sector of Southern National Park, and two game reserves on the border with the DRC. The concepts described below are bespoke to this area and it is not suggested they could be replicated elsewhere without tailoring.

Context is everything: there is no standard model

South Sudan’s wildlife estate is underdeveloped in all respects, reflective of its turbulent history. Some 14% of its land is designated as wildlife Protected Areas (PAs) and, while the range of species is vast, numbers have been decimated. In many areas, the original species baseline is simply not known. Local perspectives on the PAs range from viewing them as natural habitat, to political territory. This is based largely on the perceived value of their resources – such as oil, pasture, agriculture or timber, or as places for hunting, or security buffers between communities.1 On the ground, PA boundaries are not demarcated except where represented by features such as a river. The resources for organised conservation work have fallen in a gap between international development and the private sector. There is no tourism – due to insecurity, amongst other things.

After independence in 2011, South Sudan produced a new National Policy for Wildlife Conservation and Protected Areas, and a draft bill that remains unsigned. It is yet to become party to some of the major conventions, such as CITES. The Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism is vastly under-capacity, though it owns a large national Wildlife Service comprised mainly of former combatants. The Wildlife Service is responsible for wildlife management but is structured on state administrative lines, rather than PAs, and often resembled a state governor’s army, rather than a conservation body. The service received little international or bilateral attention during earlier reforms of the security sector.

There are few conservation organisations with the stomach to work in an environment like this. Fauna and Flora International (FFI) and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) are the only international NGOs currently working on wildlife conservation in South Sudan. The collaboration and management agreements between these organisations and the government are based on advisory and technical support, including capacity building and, importantly, support for community conservation initiatives.2

The most effective conservation governance arrangements during war, and how they might affect the interpretation and operationalisation the ILC’s principles, is an important area of research. FFI’s arrangements enabled it to remain neutral and not be drawn into the conflict, something that other governance arrangements might be compromised over, in turn forcing an organisation’s departure from a conflict-affected area.

The battlefield is not everywhere

After the events in the capital Juba in December 2013 that began the third civil war, the fighting rapidly spread north and east to the oil states. Quite simply, there was insufficient military capacity for the fighting to occur everywhere all the time. And, like any military campaign, key war-winning objectives were prioritised. In a zero-sum game of patronage and proxy, where the wealthiest man wins, the race was for control of the country’s number one resource: oil. This left many parts of the southern Equatorian belt relatively stable for months, almost in a phoney-war period. For FFI, this was the critical time to demonstrate, through actions, the intent to continue work in the PAs, maintaining and strengthening relationships, and “keeping peoples’ minds from the fighting”.3

The destabilisation of the Equatorias began as a trickle, a carefully managed series of destabilising operations, which stoked the emergence of a local opposition. By maintaining a presence in wildlife conservation, it was possible for FFI to retract its footprint and carefully expand back into areas quickly, as the situation allowed. FFI now works across all the areas it worked in prior to the civil war, which was achieved much earlier than the country-wide ‘end’ to the civil war.

There are two separate conservation issues here: first, the threat to people and the matter of safety of those working on wildlife conservation; and second, the threat to wildlife and the management of PAs. One might assume that these two issues occur in the same time and space, but it was not so. Most studies of the environmental impact of war have focused on military action, the kinetic effect of munitions and the high-technology military industry as a whole.4 South Sudan’s war was low-tech, though brutal, so it was necessary to look away from the battlefield, and its direct threats to conservation staff, to see the effects on the environment.

The displacement of civilians has been a systematic process of the civil wars, with this latest conflict creating a man-made famine and acute food insecurity for millions of people. With displacement, the greater environmental impact often occurs where people are displaced to, rather than where they fought or fled from. And in this case, the indirect impact of war on wildlife can be greater than the direct impact, and research focused in safe areas can reveal more than studying the impact on the battlefield.

Around the PAs in Western Equatoria, the greatest threat to biodiversity was the issuance of illicit forestry concessions, and the rapid logging of plantations linked to elites on all sides of the emerging conflict. Timber could have been the state’s anchor of stability and opportunity for growth for decades, but it was being quickly cleared out to fund the conflict.

What emerged from this was the need for a humanitarian approach to wildlife conservation due to the indirect effects of war; and that working with people to protect the habitat as a whole was more important than focusing on the species living in it. The risk lay in the perceptions of what managing PAs involved, and it was necessary to keep the focus of all parties on the management of wildlife habitat, rather than the protection of politicised territory.

The urban-rural fault line

The first point concerned time and space on a national scale. This second point discusses space as a localised issue in the conduct of the war. It was clear from an early stage that, like the previous civil wars, this one would be fought along lines of government-controlled urban centres, and opposition groups fighting from the bush: an urban/rural fault line that was absolutely tied to political sides. By its nature, wildlife conservation is practiced in the bush and therefore, to protect wildlife habitat, activities must continue to be focused in the PAs and with the surrounding communities.

However, it was still necessary to maintain a strong foothold in the town, i.e. with the government and where the state Wildlife Service was headquartered. This was necessary for the legitimacy of FFI and its mandate – a Memorandum of Understanding – to work in the country. Working with people and bringing them together across this urban/rural fault line would be critical. The Wildlife Service itself is locally recruited and includes many personnel from rural communities; and many people living in these rural areas identified with neither side of the conflict. Personal connections were vital, since structurally the Wildlife Service represented ‘government’ and so it became a target for the opposition. To say you were ‘going to the bush’ meant you were joining the rebels.

Six months after the war started, and while the Equatorias remained stable, the creation of joint management teams was established at a course for ‘Community Wildlife Ambassadors’ (CWAs), and the Wildlife Service rangers. The course, held deep in the bush, organised a visit for politicians, commanders from across the security sector, traditional leaders and other stakeholders: everything was transparent. Since its initiation, the CWA model has grown, become popular and embedded itself with the rural communities and the Wildlife Service alike.

Based on the principle that rural populations living nearest PAs need to be involved in their management and decision-making, individuals were recruited from local communities, trained and subsequently conducted joint management of the reserves with the Wildlife Service. Recognising the difficult position that the Wildlife Service would be in during the coming war, the CWA model was also designed to cross the emerging fault lines between the perceptions of urban/government and rural/opposition, in order to continue practising conservation management in the rural areas.

The model is like one used in Gorongosa National Park in Mozambique, which was put in place some years after their civil war and has been recognised as an excellent example of post-conflict collaboration and peacebuilding.5 In the case of Western Equatoria, and recognising the cycle of before, during and after conflicts, the creation of a joint ranger/CWA management model was put in place before the fighting started. It was most successful in areas where it acted as a method of conflict mitigation, preventing local areas falling to the fighting right through the civil war. Where it was unable to do so, it has become a rapidly re-formed model to initiate early post-conflict recovery of the PAs.

National Parks and nation building

Adding to time and space, the third dimension is scale. This is best explained in the collapse of the nation of South Sudan and the question, why and for whom do we protect wildlife in war? After an almost unanimous referendum, at independence the South Sudanese were united as a nation, full of hope for the future. Rangers were excited to be learning how to manage PAs that would benefit all South Sudanese, it was about development and progress, no longer war and trauma. The third civil war destroyed the identification of a nation and of doing things on a national basis.6 For those on the ground, the motive to manage PAs no longer had anything to do with a country called South Sudan.7

There are many layers to South Sudan’s conflict and to simplify it undermines any attempt to understand it. The collateral effect of a power struggle between elites, the war now manifests itself on the ground and in different parts of the country as a series of local antagonisms that cannot be reduced into a single broader dynamic. These localised conflicts violently contest sub-national objectives, usually over control of natural resources.

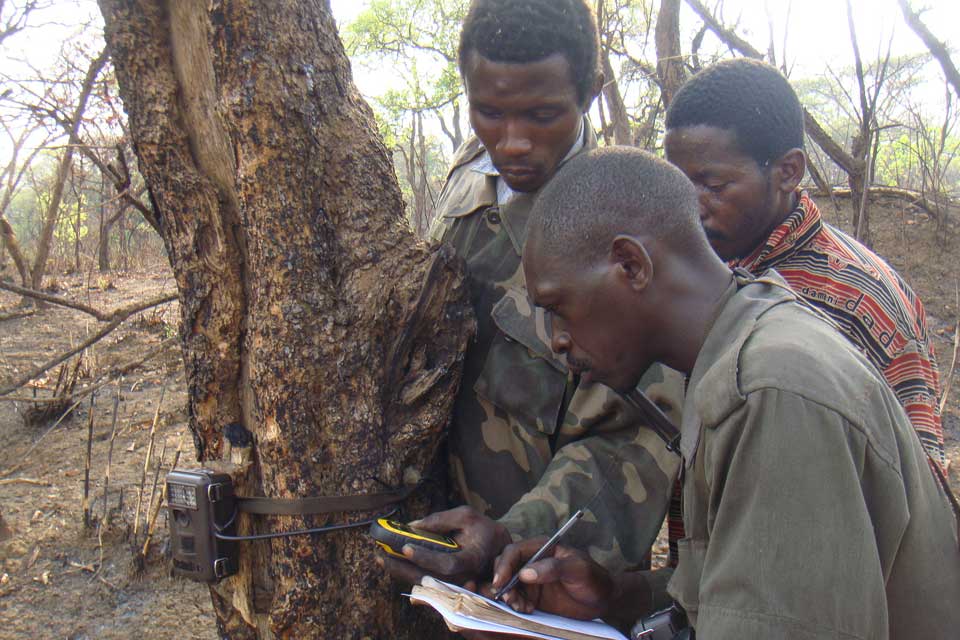

It would have been easy for the management of PAs to unintentionally become embroiled in these local antagonisms. As such, the use of non-violent methods to empower the management of PAs was vital. The Global Positioning System (GPS) is a powerful tool and one quickly grasped, and data from GPS coordinates informed the production of new maps of the PAs, with local names and information. Perhaps most critical was the deployment of remote-sensing camera traps to identify the breadth of wildlife that relied on the habitat.8 Together these activities enabled non-antagonising local ownership of the land, the wildlife habitat, with the full engagement and support of the national Wildlife Service. During the war, camera traps were recording species not previously known to exist in these areas, demonstrating their unique biodiversity. As a result of this knowledge and the desire of the communities and Wildlife Service to ensure their clear designation, demarcation of one game reserve was achieved during the civil war through a fully inclusive and legal process.9

In time, there is a role that wildlife conservation and the management of PAs could play in rebuilding identity and the nation of South Sudan. If that is to be the case, a principle of conservation that endures before, during and after conflict is that indigenous communities living in and around PAs must be included in the management, decision-making and benefits of those PAs.

Conclusion

This short discussion on time, space and scale of war and its effect on wildlife conservation leaves out a thousand other important factors. As is so often the case amidst chaos whenever something went well, an insurmountable barrier was removed, or a step forward made, there was always an individual that played a pivotal role in achieving that success. Those individuals came from all sides of the fault lines; they were not all conservationists; but they each have first-hand experience of the character of South Sudan’s wars and have themselves endured the cycle of ‘before-during-and after’ conflict several times over.

It is important to note that the CWA model is bespoke to the area of South Sudan’s Game Reserves, and that models should be developed relative to their local context. But there is much value in the broader, highly politicised aspects of working on conservation amidst civil war. Flexibility is vital (including flexible funding): the practice of war dominates and wildlife conservation activities must be responsive to this. However, those involved in conservation management at all levels, must also position for what might happen next and, therefore, understand the conditions associated with the temporal phasing of conflict.

Adrian Garside established FFI’s Western Equatoria programme in 2011. He has spent much of the past 10 years working at the interface of natural resources, wildlife conservation and armed conflict in South Sudan.

- In the area of Western Equatoria, there has been no resettlement of human populations out of PAs.

- Mujon Baghai et al, Models for the Collaborative Management of Africa’s Protected Areas, Biological Conservation 218 (2018) 73 – 82.

- A statement made by the state Governor at the time, in support of FFI’s work.

- For example, Gary E. Machlis and Thor Hanson, Warfare Ecology in Bioscience vol 58, Issue 8, 1 September 2008, pp729-736.

- John Hatton et al, Biodiversity and War: a case study of Mozambique, Washington, D.C.: Biodiversity Support Program, 2001.

- Meron Tesfamichael, South Sudan and the Complications of Peacebuilding through State Building. Kujenga Amani, Social Science Research Council, New York, March 2014.

- Author’s experience of working on wildlife conservation in various parts of the country from before and during the civil war.

- The introduction of camera traps and the production of maps has been hugely influenced and funded by Dr DeeAnn Reeder of Bucknell University, P.A., a long-standing partner with FFI’s programme in Western Equatoria.

- The written boundary of the game reserve in its original Gazettement in the 1930s was very vague, known better on the ground by community members and Wildlife Rangers with some disputed points. The demarcation process involved the agreement of all parties, digitally recording the boundary with GPS for the first time and marked on the ground (but not fenced).