Country brief: Syria

Conflict

The Syrian Civil War began in 2011 after the government sought to crack down on democratic protests that were part of the wider Arab Spring. It subsequently developed into a quasi-international armed conflict involving regional and international powers and dozens of non-state armed groups.

Key environmental issues

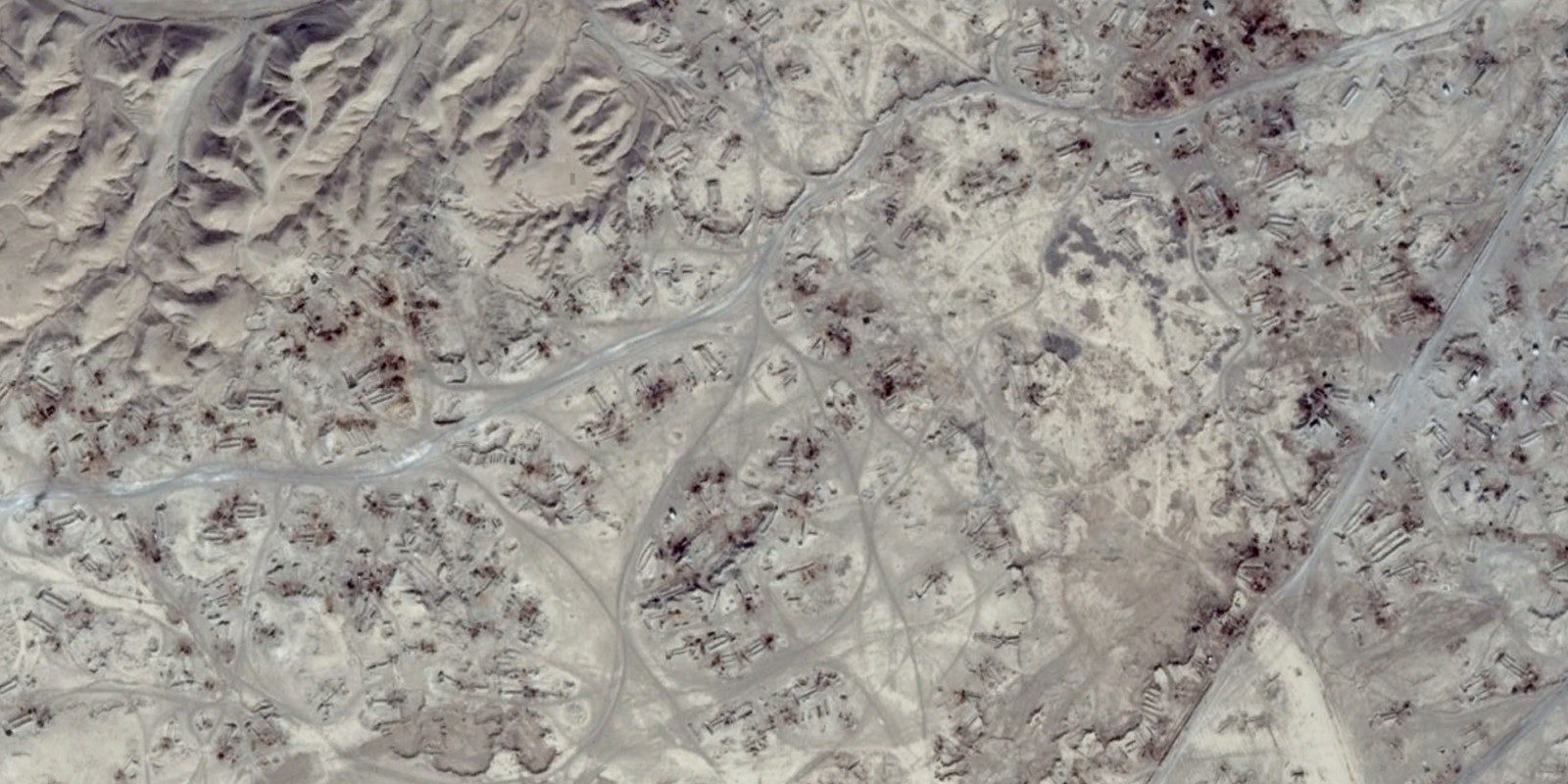

Syria’s pre-war oil industry has been the focus of attacks by all parties to the conflict. The capture of wells and refineries by opposition groups and Islamic State saw facilities regularly bombed by Russian and US aircraft, causing localised pollution. This policy, whose aim was to deny oil revenues, had little effect on demand for oil products, and caused the civilian population and armed groups to turn to informal oil refining methods; the highly polluting process has affected communities and the environment across Syria’s oil producing areas.

Intense fighting in urban areas has generated vast quantities of rubble and waste, and has affected residential and industrial areas, potentially creating pollution threats. Critical environmental infrastructure such as energy, water and sewage systems have been deliberately targeted or suffered damage, causing pollution and increasing public health risks. Inadequate pre-war solid waste management systems have deteriorated further or have broken down entirely in conflict affected areas. Environmental contamination from the intensive use of conventional weapons is also likely to be widespread.

Massive population displacement within Syria has placed increased environmental pressures on cities and rural areas, while neighbouring countries hosting large refugee populations, such as Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey have also faced environmental pressures. Environmental governance in areas affected by the conflict and beyond government control has been heavily disrupted, while the impact of the conflict on biodiversity and protected natural areas remains unclear. Agricultural areas have been heavily contaminated by explosive remnants of war.

| In figures | |

|---|---|

| Volume of government oil production lost between 2010-14 | 97.5% |

| Oil infrastructure targets destroyed by US led coalition 2014-16 | 2,368 |

| Growth in artisanal oil refineries identified by satellite imaging 2010-15 | 0-5791 |

| Homes damaged destroyed in Aleppo 2011-15 | 52% |

| Homes identified as damaged in Syria’s 10 largest cities 2017 | 238,311 |

| Homes identified as destroyed in Syria’s 10 largest cities 2017 | 78,339 |

| Estimated volume of debris in Aleppo | 14.9m tons |

| Estimated volume of debris in Homs | 5.3m tons |

| Power stations rendered inactive 2011-14 | 30 |

| Proportion of electricity transmission lines attacked 2011-14 | 40% |

| Protected natural areas pre-conflict | 26 |

| Sources: World Bank, PAX |

International and domestic response

The enormous human cost of the Syrian Civil War has overshadowed its environmental consequences, while the geopolitical complexity of the conflict make it questionable whether the environment will be properly addressed if peace is reached. Thanks to initial studies by civil society, actors such as the World Bank have included environmental issues in damage assessments but validating these will require field access. The UN Development Programme has been working on projects to restore critical infrastructure and address debris and waste. Environmental pressures in Lebanon and Jordan,1 which both host large refugee populations, have influenced domestic politics and government policies.2

Since 2016, the Assad government has highlighted the environmental dimensions of the conflict in international fora, branding it an environmental disaster. In 2017 they placed the blame for damage to oil and vital civilian infrastructure on “terrorist groups” and the US-led coalition, and argued that economic and political sanctions are hampering environmental restoration projects.3 They also called for states and the UN to support environmental programmes in Syria. If peace is achieved, the outcome of the conflict will strongly influence Syria’s ability to attract international donor support for environmental assessment and remediation measures.

Further reading

PAX (2015) Amidst the debris – a desktop study on the environmental and public health impact of Syria’s conflict:

https://www.paxforpeace.nl/publications/all-publications/amidst-the-debris

PAX (2016) Scorched earth and charred lives – human health and environmental risks of civilian-operated makeshift oil refineries in Syria:

https://www.paxforpeace.nl/publications/all-publications/scorched-earth-and-charred-lives

von Lossow, T (2016) The Rebirth of Water as a Weapon: IS in Syria and Iraq. The International Spectator Vol. 51 , Iss. 3:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03932729.2016.1213063

World Bank (2017) The Toll of War: The Economic and Social Consequences of the Conflict in Syria:

http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/syria/publication/the-toll-of-war-the-economic-and-social-consequences-of-the-conflict-in-syria

- United Nations (2017) Lebanon Crisis Response Plan 2017-2020: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2017_2020_LCRP_ENG-1.pdf

- TRW Project (2016) Jordan grapples with the environmental consequences of its refugee crisis: https://ceobs.org/jordan-grapples-with-the-environmental-consequences-of-its-refugee-crisis/

- Foeke Postma (2017) What governments said about conflict pollution at UNEA-3: http://www.trwn.org/what-governments-said-about-conflict-pollution-at-unea-3/