Russia’s indiscriminate use of heavy weapons in urban areas is increasing the risks from damaged energy, industrial and commercial sites.

This update provides an overview of some of the environmental trends caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It builds on our initial rapid assessment, which was published on Feb 25th, and which provides more context for the trends discussed below.

Health warning

The incidents we summarise below are primarily based on social media monitoring, which can be unreliable. Where possible we have used trusted sources but the reports may be subject to change as further information comes in. As importantly, while we can document the kinds of problems associated with certain incidents, in the vast majority of cases their true humanitarian or ecological impact will only be properly understood after assessment on the ground.

Introduction

Russia’s initial strategy to rapidly subdue Ukraine by taking Kyiv, and occupying strategically important border regions proved unsuccessful. The strategy led to a large number of polluting strikes against military infrastructure – chiefly airbases and ammunition storage areas – in the first 48 hours. Environmentally important border areas were occupied – the Chernobyl zone in the north, and Kherson Oblast and the North Crimean Canal to the south.

As Russian military progress has slowed, we have seen a shift to urban siege warfare, involving the use of indiscriminate heavy explosive weapons and airstrikes in order to subdue towns and cities. This is changing the pollution risks that we are seeing, from predominantly military sites, to those from industrial and commercial properties, which in places are sited close to residential areas.

There is growing concern over the environmental threats that this highly destructive warfare in a heavily industrialised country is creating. Russia’s track record on the protection of civilians, its conduct thus far, and its views around the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts mean that those concerns are justified. At the UN Environment Assembly, which concluded this week, 108 NGOs backed a statement deploring Russia’s actions and calling for support to monitor and address the environmental harm being caused. Meanwhile, an open letter addressing environmental concerns attracted more than 1,000 expert and organisational signatories from the field of environmental peacebuilding. The conflict’s environmental narrative is being picked up by the media (for example DW, WIRED, Inside Climate News, Politico, BBC World Service), particularly in the wake of Russian military actions around nuclear sites.

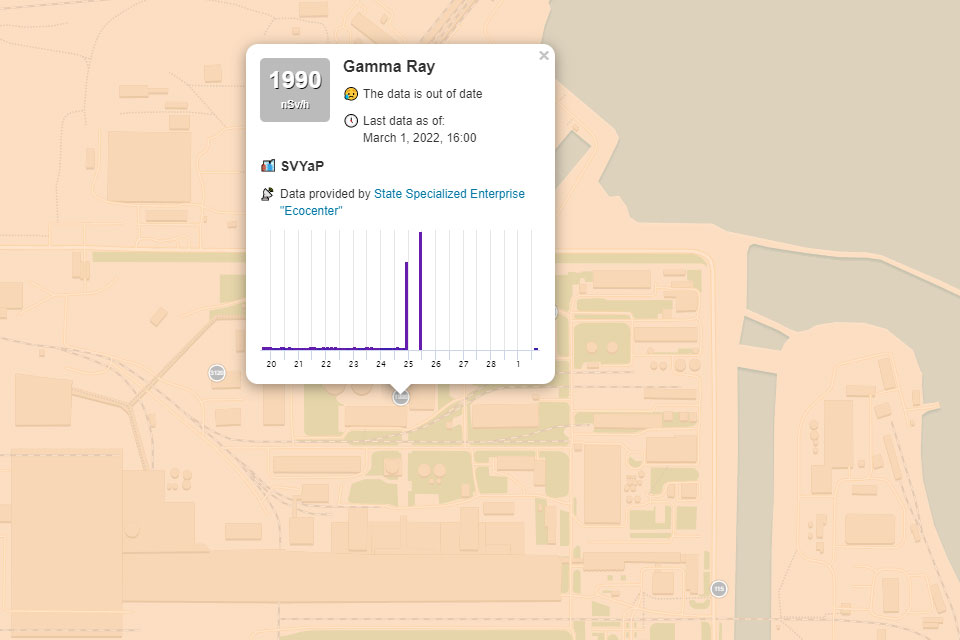

Ukraine’s well-developed system of environmental monitoring stations, accessible via SaveEcoBot.com reveals how the conflict has disrupted day to day monitoring of air quality and radiation. As of the 5th March, of 1,357 air monitoring stations, only 482 had submitted data in the previous 48 hours, while only 149 of Ukraine’s 331 radiation monitoring stations were online – with no public data available from its four active nuclear plants.

For external observers, heavy clouds have prevented the use of optical satellite imagery but researchers have been sharing other techniques, or deploying existing methodologies in new ways, for example, using Synthetic-aperture radar to monitor the Russian naval build-up.

Military installations and materiel

Having intensively targeted nearly 100 military locations with cruise missiles and airstrikes in the first two days of the conflict, such as sites like Vasylkiv airbase and an ammunition store at Balakliia, Russia began shifting to the remaining lower priority infrastructure of military value. One of these was Borodyanka airfield, near Kyiv, a civilian airfield which was targeted on the 28th February leading to a major fire in its fuel storage tanks.

With Russia’s focus broadly shifting from military sites to urban areas, we saw far fewer incidents at military sites, for example a suspected strike at Chuhuiv, near Kharkiv. We also saw a suspected Ukrainian strike just over the Russian border.

There has been a general trend away from point sources of pollution at damaged military installations, to much more widespread pollution from damaged and burnt out military materiel, with hundreds of vehicles destroyed, and concentrations of wreckage along roads in urban and rural areas.

Nuclear sites

The dangerous situation at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, Europe’s largest and home to six reactors, has helped to eclipse the extraordinary and increasingly unsustainable situation at the Chernobyl site, which Russia’s military occupied on the 25 Feb. Spikes in gamma radiation readings around the site’s core buildings were spotted before the monitoring system went offline for two days. When monitors came back online, under Russian control, those where the highest peaks were recorded were still offline.

On 3 March, the IAEA confirmed that Ukraine no longer had regulatory control over the site, and that its staff faced “psychological pressure and moral exhaustion”. By 5 March, there were more worrying signs of the toll that the occupation was having on staff at the site, with the local mayor reporting that:

“We can’t replace people, they have been working their shift for 10 days. They split into two groups, taking turns, but they were tired morally and physically, emotionally. People eat a limited diet, they have a limited amount of medicine and it is very difficult for them.”

Although we were one of several voices highlighting the risks that fighting in proximity to the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant could pose, it was nevertheless shocking to see these fears realised. The overnight battle at the plant followed a tense afternoon, with fires surrounding the town of Enerhodar next to the plant, and its people forming a human barricade in an effort to prevent Russian troops from accessing the site.

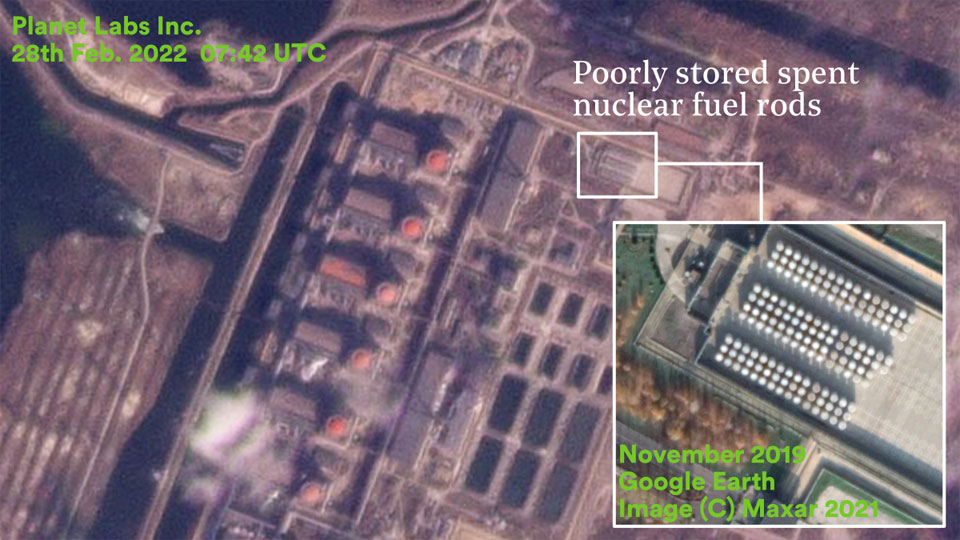

While much of the coverage focused on the plant’s six reactors, there was little attention on the large volumes of radioactive waste stored in the open air at the site. Warnings had been issued since at least 2015, with Friends of the Earth commenting at the time that: “With a war around the corner, it is shocking that the spent fuel rod containers are standing under the open sky, with just a metal gate and some security guards waltzing up and down for protection.” As it was, the damage was focused on a training building at the site. Footage of the site’s control room staff pleading with the Russians to stop firing was released to the New York Times.

The largely unprecedented nuclear dimension to this conflict has brought the role of the IAEA into sharp focus. Its members adopted a resolution deploring Russia’s actions, while its Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi has been in touch with both sides, and has been holding daily press conferences, even offering to visit Ukraine in person. But the agency’s ability to influence the situation remains more technical than political, for example when asked if it could enforce a 30km exclusion zone around Ukrainian nuclear facilities the agency said that was not within its mandate. Social media memes began demanding that the nuclear plant risks be a justification for the imposition of a NATO no-fly zone.

Demand that your politicians close the sky over Ukraine. Ukraine has 15 nuclear units. This is a huge danger for the whole of Europe.

If Russia blows up one power, it will be a catastrophe for the whole of Europe#stoprussia pic.twitter.com/9v9iWpiv2x— Stratcom Centre UA (@StratcomCentre) March 5, 2022

So far, the South Ukraine Nuclear Power Plant north of Mykolaiv has been spared the fighting, but this may change shortly. As of March 5 its official website was offline. And the situation remains that it is not just the highly visible nuclear plants that pose radiological risks, two low level waste storage facilities were damaged by artillery and missile fire, one of which was located in Kyiv.

Other energy infrastructure

Indiscriminate shelling and deliberate strikes have affected civilian energy infrastructure in many of the towns and cities where Russian forces have attacked. The destruction of power generating sites has a direct impact on civilians, making it more likely that they will flee urban areas, when this is possible, increasing human suffering where it is not. Damage to them can also generate pollution risks, whether from burning fuels or from the materials they may contain, such as PCBs.

Okhtyrka Combined Heat and Power Plant was reported to have been completely destroyed by a Russian airstrike, and its transformers damaged. Far lighter damage was reported to Zuevskaya Thermal Power Plant. At least three large diesel tank farms were struck, leading to very large fires at: the Комбинат Астра tank farm in Chernihiv, an oil terminal in Okhtyrka near Sumy, and a fuel depot and lubricant warehouse in Mykolaiv.

Shelling of oil terminal in Okhtyrka, Sumy Oblast. Geolocated here: 50.317222, 34.872474 – https://t.co/rYyDzBLFGU https://t.co/fXhDjIsq7e pic.twitter.com/YXR0mE5Ha5

— ваят (@bibken) February 28, 2022

The Gas Transmission System Operator of Ukraine has reported that heavy fighting has caused widespread damage to gas pipelines, with 13 distribution centres disconnected as of March 4, leaving thousands in cities without gas. In some cases these incidents have led to large blazes, for example in Kharkhiv. Naftogaz’s Ukrtransgaz JSC, which operates gas storage and pipelines confirmed that it has received a Starlink satellite internet kit to allow it to better coordinate repairs and distribution.

Water, rivers and the sea

The use of heavy weapons has led to numerous reports of disruption to water supplies, whether through physical damage to pipelines, as pictures circulated on Telegram documented in the town of Chernihiv, or in connection to the loss of electrical power. Ukrainian forces have been destroying bridges to prevent Russian troop movements, with the potential for debris and contaminants to disrupt river habitats. Likely more serious are emissions of pollutants to rivers following fires at industrial or commercial sites, and the efforts to fight them.

We also began to see more scope for coastal pollution incidents; these were initially linked to strikes on naval facilities but this has now shifted to attacks on vessels, such as the Banglar Samriddhi off Mykolaiv, or the Helt off Odesa, which was initially thought to be a Russian naval vessel on fire. In addition, the Ukrainian navy scuttled its flagship the Hetman Sahaidachny, which was in Mykolaiv port undergoing repairs.

A developing water issue is Russia’s unblocking of the North Crimean Canal, to allow water to once again flow to annexed Crimea. Local reports quoted the governor of Crimea as saying that it will take several weeks for water supplies to once again reach the whole peninsula, perhaps providing a window on the minimum degree of permanence Russia is expecting from its occupation of southern Ukraine. Given the political pressure Russia came under over the water crisis in Crimea, it seems likely that it has permanent control of the canal as an objective.

Explosive weapons in commercial and industrial areas

As the fighting increasingly focused on urban areas, we began to see environmental health risks emerge from the use of indiscriminate explosive weapons. These risks encompass inhalational and ecological risks from pulverised building materials, emissions from environmentally hazardous sites and infrastructure, as well as the longer term problems associated with debris management. In places, damage to residential buildings is severe.

While serious concerns are ongoing over industrial infrastructure, in addition to the energy generation and storage sites discussed above, we also saw damage to commercial sites that could pose environmental risks. This included serious fires at: a manufacturer and storage site for foam insulation in Buchansky, a warehouse in Kharkhiv, a distributor of vehicle parts on the outskirts of Kyiv, a warehouse in Mariupol, and a huge blaze at an Epicentre K home improvement store in Chernihiv.

Fire at manufacturer and storage of insulation foam in Buchansky district of #Kyiv #geolocated #Ukraine https://t.co/GmYfgdXmkk pic.twitter.com/irUEoWYkDF

— Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS) (@detoxconflict) March 3, 2022

As noted in our initial assessment, many of Ukraine’s cities have extensive industrial sites, including Kyiv, Kharkiv, Kryvyi Rih, Mariupol and Odesa. Over the last few days, Mariupol has joined Kharkhiv in facing intense bombardment by Russian forces. The city is home to two large iron and steelworks, and more than 50 other industrial enterprises. It is one of the most polluted cities in Europe and its mayor has been posting daily updates on conditions in the city. On March 3 the mayor wrote: “Deliberately, for seven days they destroyed the city’s critical life support infrastructure”.

Mariupol’s Avostal and Illich iron and steelworks are both owned by Metinvest, which owns a wide range of industrial and mining enterprises in Ukraine. The company has been posting regular updates of the measures it is undertaking at these sites in order to reduce the risks they could pose. These include “cold canning” of its metal works, and the shutdown of unnecessary processes. It has also sought to reach out to Russian miners and metalworkers to tell them of the situation in the city. As with the nuclear power plants, sites are implementing emergency procedures to reduce the risk of environmental emergencies. Another example of this was the decision to suspend the operation of the Togliatti-Odessa ammonia pipeline, the world’s longest, by its Russian owner, Togliattiazot.

Global food security

Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of globally important agricultural commodities and fertiliser. As with oil prices, the invasion is already pushing up the prices of wheat and sunflower oil – in the latter’s case forcing India to ask Indonesia to increase the supply of palm oil. With food prices already at a 10 year high, these trends are leaving a range of countries highly exposed, particularly in the Middle East. For Kazakhstan, a poor harvest this year has left it in greater need of imports. Egypt is reliant on Russia and Ukraine for 80% of its wheat imports and potentially at risk of political instability because of the demand for bread. Drought in Iraq has left it requiring far more wheat imports this year, while for Yemen, food price spikes directly impact the cost of humanitarian assistance, meaning less support for its people from the squeezed budget of the World Food Programme.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director, Eoghan Darbyshire its Researcher.