Nature-based solutions can help make communities less vulnerable to the climate crisis, our new study explores how they can be impacted by war.

Mutually beneficial relationships between people and the ecosystems they inhabit are fundamental to people’s long-term well-being. When these relationships are interrupted by external shocks, the breakdown of people-nature relationships often adds to post-disaster hardships. In a new report, we show that this is currently happening as a result of an ongoing war between Ethiopia and Tigray, one of its northern states.

The ecology of agriculture in Tigray

Food security in semi-arid tropical Tigray depends on rainfall-based agriculture. Most of Ethiopia’s population depends on subsistence agriculture for a large part of their diet, and when rains are late or sparse, alternative sources of income or food are often insufficient, contributing to catastrophic famines, such as in the 1980s.

“Traditional” agricultural development policies – those that focus on improving material inputs and economic structures, e.g. farmers’ access to fertilizers, loans or markets – have only had modest effects on agricultural productivity in Tigray. In the 1990s, the Tigray government instead adopted a conservation-based agricultural development policy to address persistent food insecurity and low agricultural productivity.

The new strategy focused on making the land better at retaining water and soil, two key ingredients of agricultural production. This included building stone and soil berms that slowed down overland water flows, reducing erosion rates; creating ponds in which runoff water could be stored; and setting up exclosures – patches of degraded land that were allowed to regenerate by banning livestock grazing and wood cutting. These exclosures act like sponges, allowing rainwater to infiltrate the soil rather than running off.

Over three decades, this approach transformed the Tigrayan landscape, leading to widespread recovery of trees and shrubs, reduced erosion and rising groundwater tables. This allowed the expansion of irrigated agriculture; and, most importantly, agricultural yields indeed increased.

War’s impact on Tigray’s landscape

However, this success has now come under threat from the ongoing war in Tigray that started in November 2020. Since the start of the war, the region has been under a blockade, leading to a collapse in food and fuel supplies. Electricity supplies have been largely disrupted and unreliable, and banking and telecommunication services have been suspended. This has created a large-scale humanitarian crisis: 1.8 million people have been internally displaced, and 83% of people in Tigray are estimated to have faced acute food shortages.

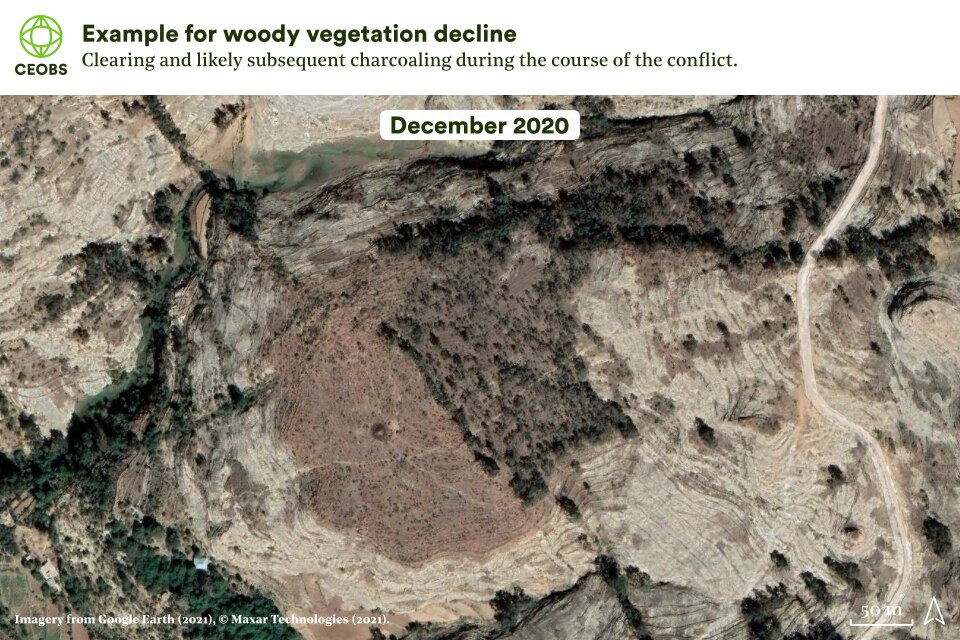

Cut off from alternative supplies for cooking fuel, people may have to turn to local sources of wood to satisfy demand, despite regulations against cutting vegetation in exclosures. Contacts in Tigray shared with us their concerns about the pressures that the energy crisis is putting on trees and shrubs. Vegetation declines were indeed visible in the few open-access, high-resolution satellite imagery available on Google Earth taken after November 2020. However, it was difficult to gauge the extent of the problem as local travel and telecommunication continue to be difficult and the region remains largely inaccessible.

Tracking vegetation changes from space

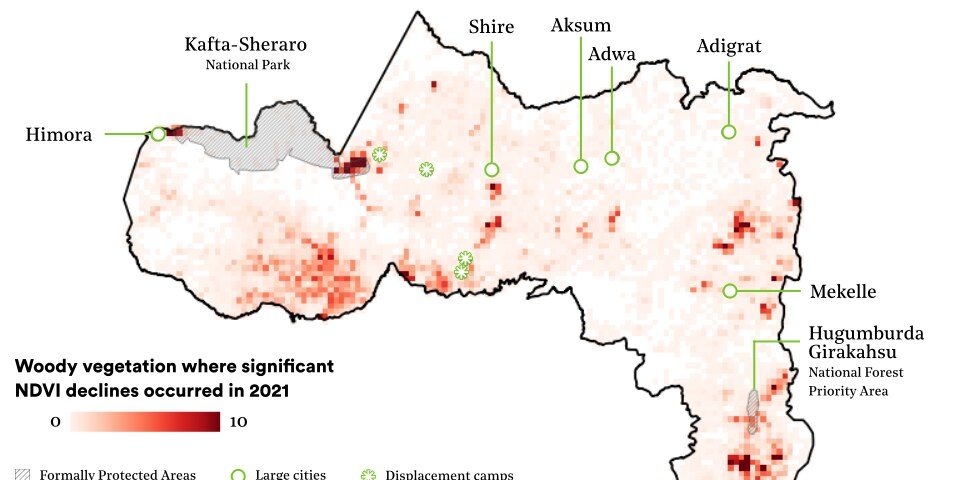

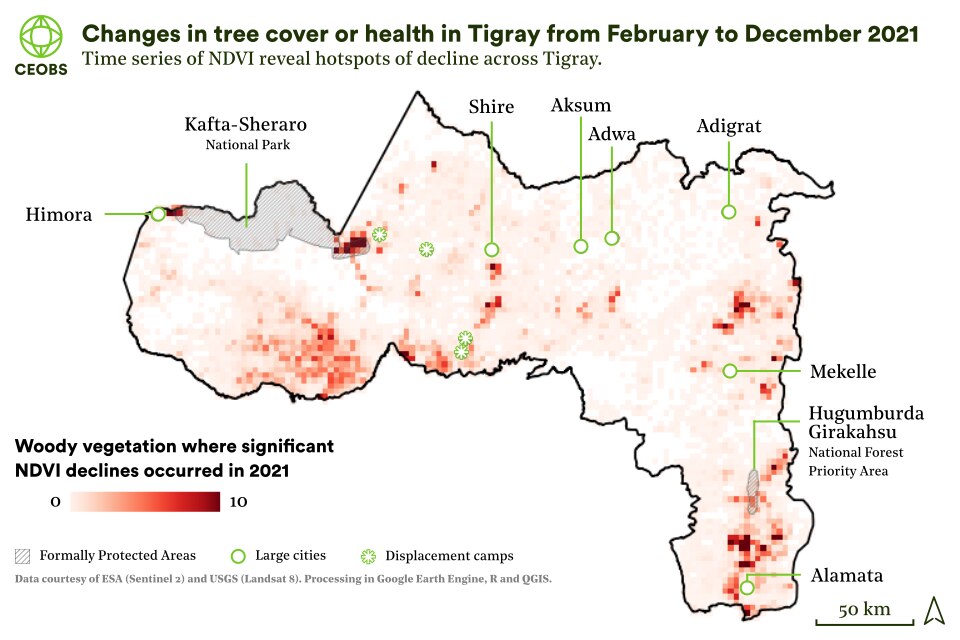

We therefore turned to Sentinel open-access satellite data, which provides wall-to-wall coverage of Tigray, to map areas where woody vegetation may have declined since the start of the war, and indeed found hotspots where this had occurred. The hotspots indicate pre-war woody areas with a strong decrease in NDVI, a commonly used index for greenness of the landscape. Potential alternative drivers of these declines – rainfall, temperatures, fires, and locust outbreaks – showed little spatial overlap with these hotspots of woody vegetation decline. Woody vegetation continued to thrive in other places in Tigray during the same period, but – when compared to pre-conflict years – vegetation recovery was subdued. This led us to conclude that woody vegetation declines were likely being intensified by the conflict.

Nature-based solutions, conflict and vulnerability

The history of the Tigrayan landscape shows that losing woody vegetation cover leads to soil erosion and water run-off, decreasing agricultural productivity in a region already suffering from widespread hunger and expecting another drought this year. In the long term, pressures from climate change – including increasing downpours, which can contribute to erosion, and droughts (especially in the west) – are likely to continue. Woody vegetation, a key soil and water conservation component, is thus being eroded at a time when it is crucial to the long-term wellbeing of people in Tigray. On a more positive note, previous landscape restoration efforts are providing a buffer for environmental impacts of the war, as losses of woody vegetation are likely occurring from a higher baseline than they would have without widespread vegetation recovery throughout the 21st century.

The environmental impact of the war is not limited to its effects on woody vegetation: the impacts on wildlife population or water cycles in the region remain to be determined. Neighbouring regions, such as Amhara and Afar, into which the conflict has spilled over since July 2021, could also be affected. It is important that the environmental impacts of the war are fully assessed on the ground to inform recovery strategies: only if the environment thrives can the long-term well-being of people in conflict-affected areas be assured.

The full report: The war in Tigray is undermining its environmental recovery is available here.

Henrike Schulte to Bühne is a conservation scientist and Honorary Research Associate at the Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London. She carried out this analysis while employed by CEOBS. We are grateful to Dr. Teklehaymanot Weldemichel, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, and Prof. Jan Nyssen, University of Ghent, for their contributions to the research. This article first appeared in The Conversation.