Joint investigation into the environmental costs of attacks on Ukraine’s Kremenchuk Oil Refinery, part 1

Published: June, 2024 · Categories: Publications, Ukraine

- Location of incident: Kremenchuk Oil Refinery (49.175, 33.462)

- Sites affected: Kremenchuk Oil Refinery and surrounding areas

- Dates of attacks: 02 April, 24 April, 12 May, and 18 June 2022

- Times of attacks (local time): Between 06:39 and 08:12 local time on 02 April

- Reported damage: Facility severely damaged

- Type of attack/munition likely used: Likely cruise missiles

This investigation was undertaken jointly by the Ukrainian Archive and CEOBS, with contributions from the The European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR).

Contents

1. About this investigation

Introduction

The environmental damage done by armed conflict is often overlooked when discussing the impact of war in a particular area. The armed conflict between Russia and Ukraine is perhaps a noteworthy exception to this, but coverage in the media, legal system, and public discussion do not always translate into action. Since Russia escalated the armed conflict against Ukraine on 24 February 2022, multiple chemical storage facilities have been struck, leading to the release of an unknown amount of pollutants into the environment. This investigation is a case study of the impacts of such incidents on the environment, via the attacks on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery. This investigation not only assesses the environmental and physical damage caused by the attack, but also analyzes existing legal frameworks surrounding reparations for environmental damage and their potential shortcomings, which make it difficult for Ukraine and other countries with similar grievances to receive reparations.

Note: The Kremenchuk Oil Refinery was Ukraine’s only functioning oil refinery when the full scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation began on 24 February 2022. The oil refinery was attacked repeatedly with missiles and/or air strikes, leading to extensive damage and the cessation of oil production. This is the first of a series of reports on the attacks, and is focused on the first recorded attack on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery on 02 April 2022.

Methodology

This investigation examines a variety of open-source documentation pertaining to alleged attacks affecting the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery, which took place in April and May 2022, during the second and third months of the full-scale armed conflict. Analysis of these materials was conducted by cross-referencing a combination of open-source visual content and public information. Specific methodologies are described in greater detail in the Methods section of Ukrainian Archive’s website.

This investigation was also undertaken with an awareness of international humanitarian law, which imposes limits to how parties to a conflict may conduct hostilities and under which civilians and civilian objects – including in particular hospitals, medical personnel, the environment and objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population – are protected. If proved, actions that violate these safeguards may constitute war crimes, human rights violations, and also potentially crimes against humanity.

Through collection, verification, and analysis of the investigative findings from these incidents, the authors hope to preserve critical information that may be used for advocacy purposes or as evidence in future legal proceedings seeking accountability.

Data ethics

The authors have strived to incorporate a “risk minimisation” ethical framework into its processes. Due to the repeated targeting of hospitals, medical facilities, and medical personnel since 2014, particularly by Russian-backed “DPR/LPR” “people’s militias” and by Russian Federation armed forces, additional precautions and ethical issues were taken into consideration.

In order to help establish that digital content is what it purports to be, rigorous verification steps, guided by the Berkeley Protocol and international guidelines on digital open-source investigations, must be taken to authenticate the findings.

2. Background on the affected area

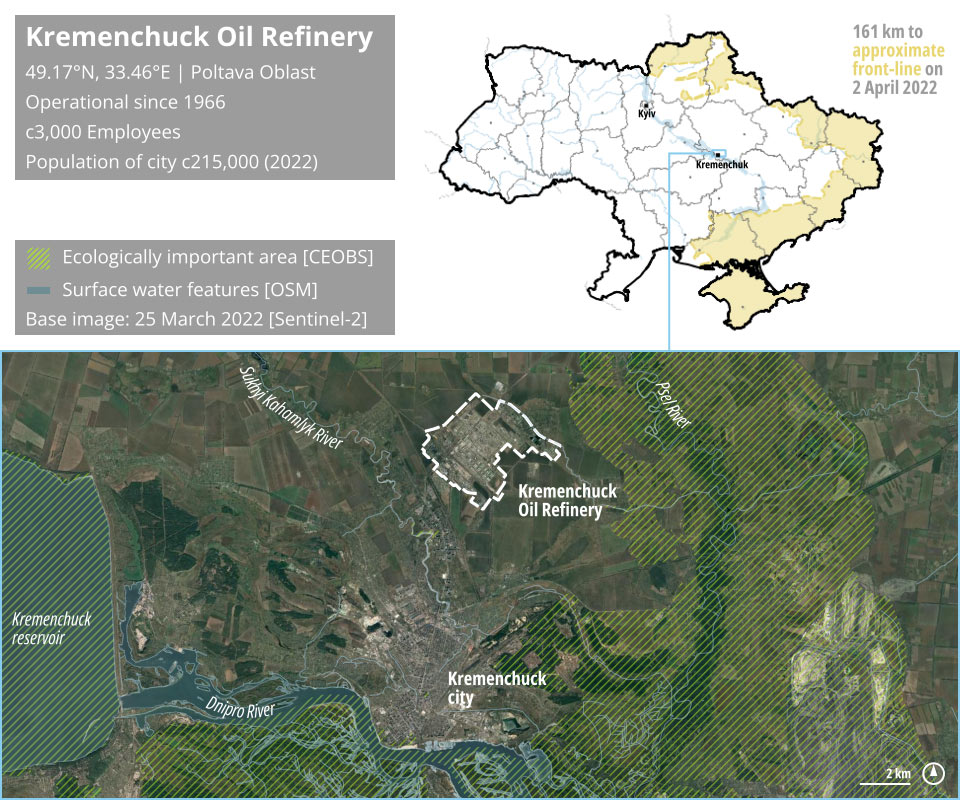

Kremenchuk

The Kremenchuk Oil Refinery sits in the northernmost section of the city of Kremenchuk, which is located on the Dnipro River in Poltava Oblast. The city is rich in iron and oil deposits, and is a major industrial center. Although always an important industrial center, its role as such grew in 2014 when Russian forces took control of many industrial areas in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts. Its factories became a target for the Russian armed forces during their assault on Ukraine in 2022.

Kremenchuk Oil Refinery

Construction on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery began in 1961, when Ukraine was a constituent republic of the USSR. The plant became fully operational in 1966 and produced a wide range of petroleum products including gasoline, diesel, and natural gas. After Ukraine gained independence in 1991 the refinery went through a series of ownership changes during the 1990s and 2000s. Despite functioning below capacity, by 2008 the plant supplied 30% of Ukraine’s petroleum market. The strategic importance of the refinery grew even further when it became Ukraine’s only operational oil refinery after the closure of the Lysychansk Oil Refinery in 2012. In 2016 the plant’s owner Ukrtatnafta announced that the plant would be transitioning to producing fuels that meet European Union standards. Despite being Ukraine’s only oil refinery, in February 2016 it was reported to only be functioning at 25% of its capacity. As of September 2021 the refinery employed approximately 3,000 people.

3. What happened and when?

Summary of online reporting

Publicly available reporting identifies multiple separate instances of airstrikes against the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery. On 02 April 2022, reports indicate that a missile attack started several fires at the facility and multiple people suffered burns as a result. Reports also indicate that the refinery was rendered at least partially and temporarily inoperable as a result of this incident. The strikes resulted in substantial fires at several sites around the refinery and the release of a large quantity of pollutants into the countryside to the north, west, and east, as well as the densely populated city of Kremenchuk to the south.

Geolocation

The Kremenchuk Oil Refinery is located in the northernmost part of Kremenchuk at coordinates 49.175, 33.462.

Chronolocation

The first recorded attack on Kremenchuk occurred on 02 April 2022 at approximately 06:00 local time according to Dmytro Lunin, the Head of the Poltava Oblast Military Administration. Later that day Lunin confirmed that his non-specific post from earlier about an “attack on Kremenchuk” referred to the attack on the oil refinery. A Telegram account which posts notifications of air raids for Kremenchuk recorded an air raid warning in that time frame, lasting from 05:37 until 07:35. Given Lunin’s statement that the attack occurred around 06:00 local time, it is probable that it took place no earlier than 05:37 local time and no later than 07:35 local time.

4. Damage caused by the attacks

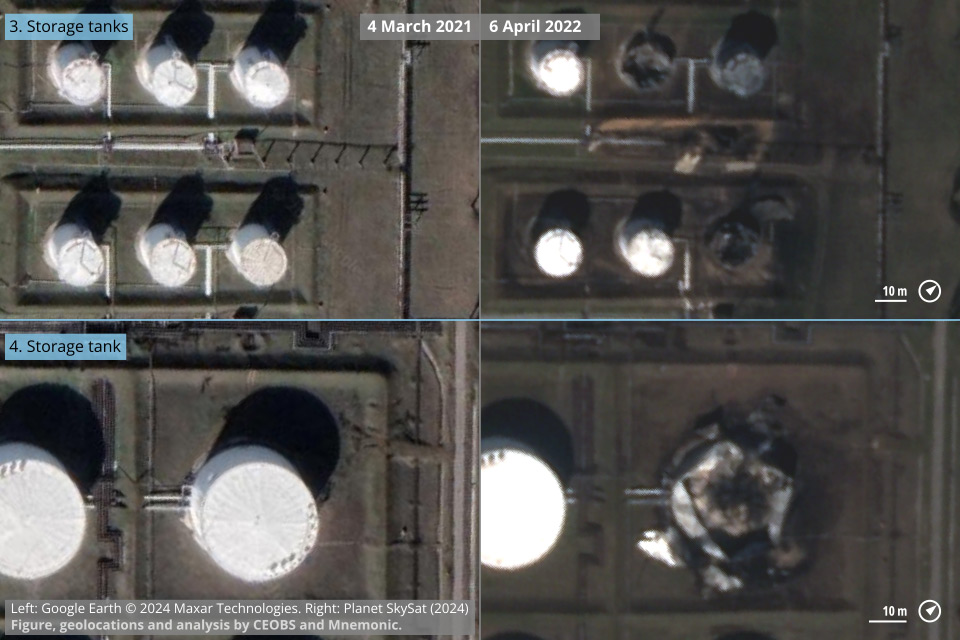

The attack caused damage to at least six sites at the refinery. This analysis is based on visual inspection of high resolution satellite imagery collected on 06 April 2022 from Planet SkySat. It is possible that there was further damage that was not detectable on this imagery, the social media footage collected, or satellite fire hotspot data.

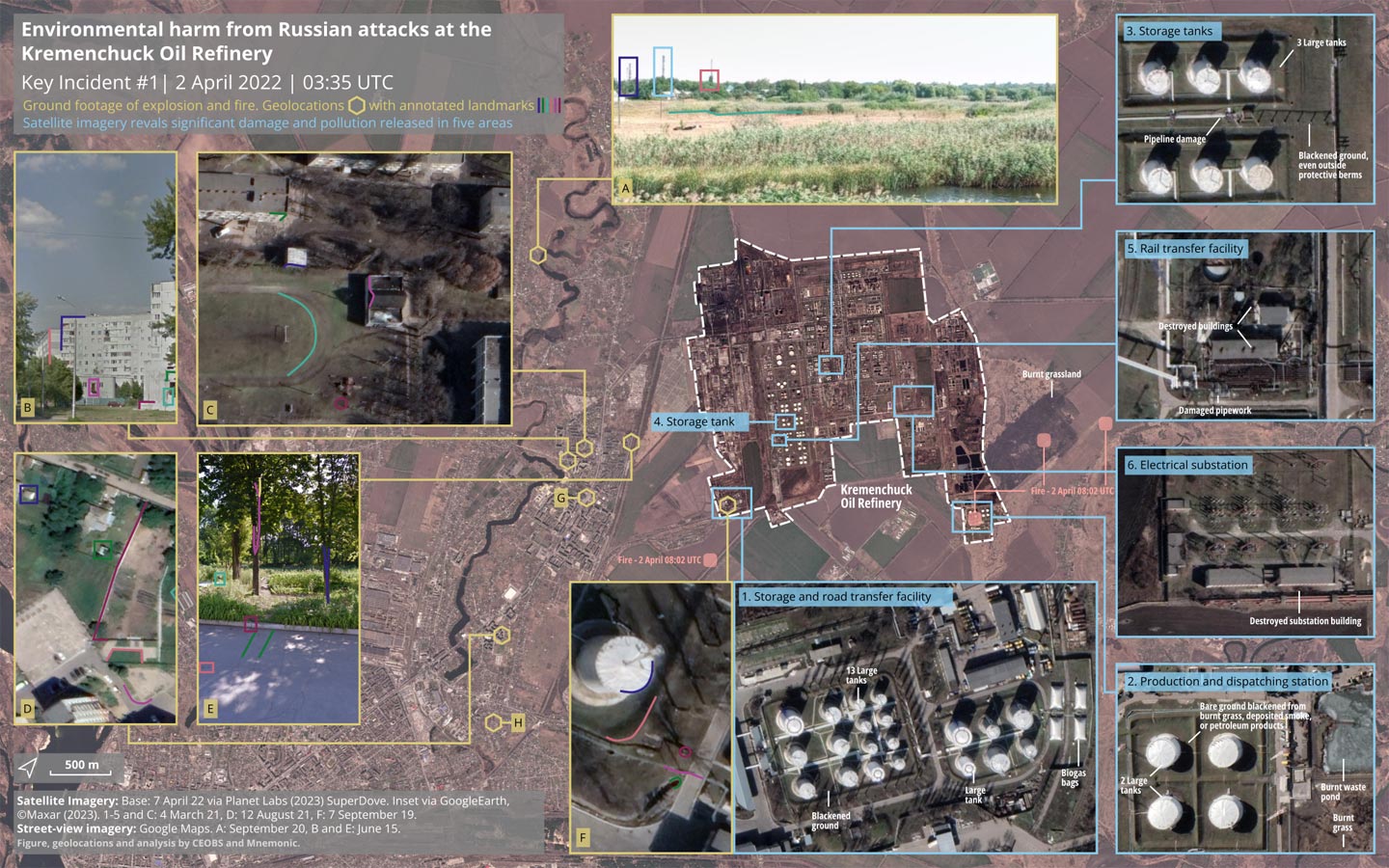

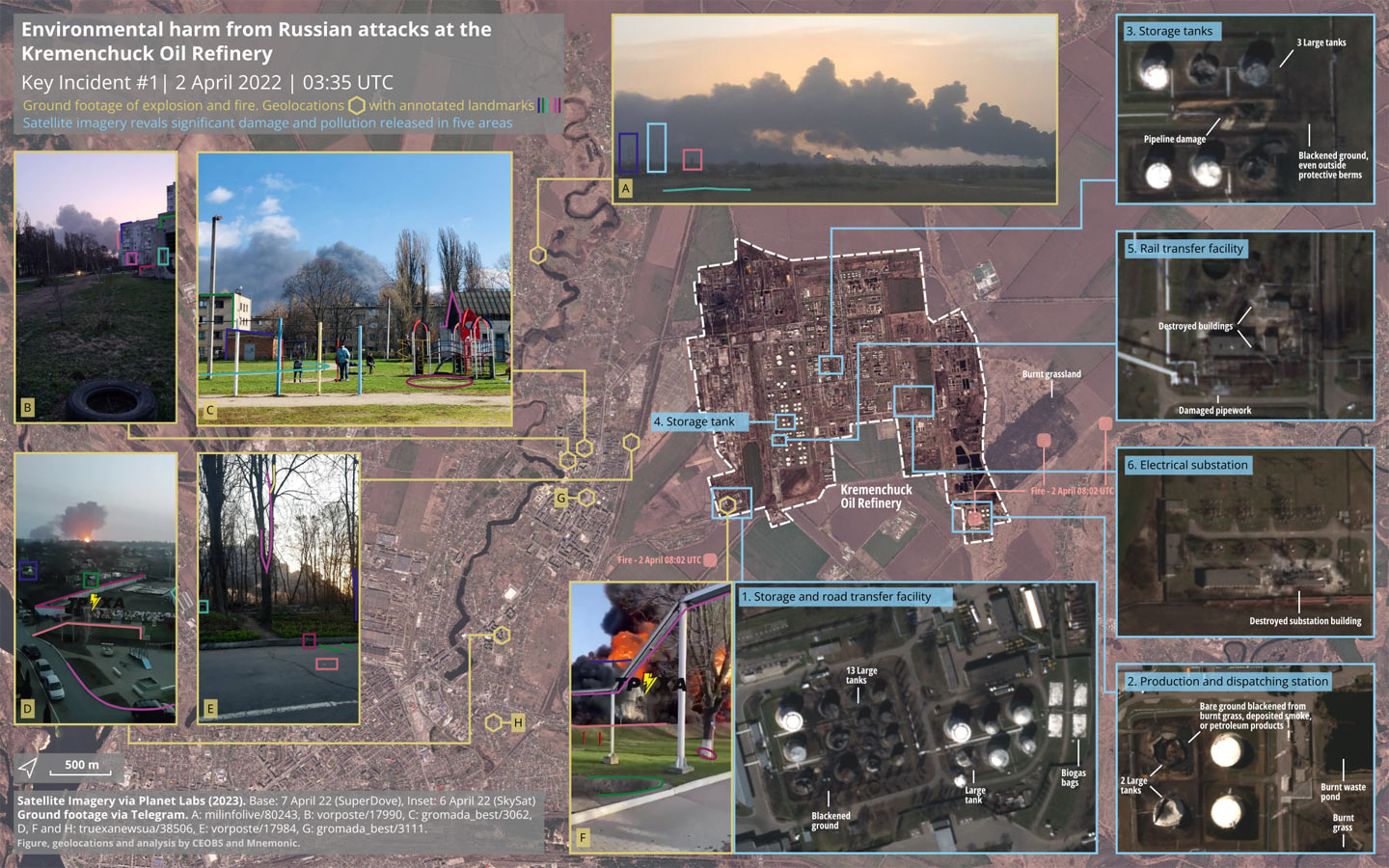

Figure 2: Summary of satellite and social media imagery of the incident at Kremenchuk Oil Refinery on 2nd April 2022

Sites 1 to 4 are locations where storage tanks have been destroyed or damaged. Site 1, a storage location where products were transferred for road transportation, suffered the most widespread damage. A total of 13 tanks and four biogas bags were destroyed or damaged. A substantial fire broke out at this site, and was detected by satellites via NASA’s Fire Information and Resource Management System (FIRMS). The fire was also visible on footage circulating online on 02 April 2022, which we have geolocated to this location (Figure 2, inset F).

Two large storage tanks were destroyed at Site 2. These likely ignited the adjacent vegetation, 100 hectares of which appear charred on satellite imagery from 06 April 2022, and where a fire was detected via FIRMS on 02 April 2022. At site 3, two tanks and a pipeline appear destroyed, whilst a further tank may also have been damaged. The adjacent ground is blackened, even outside the protective berms, indicative of burning, spilled oil, or both. At site 4 a large tank was destroyed, bringing the total number of large vertical storage tanks damaged or destroyed to at least 19.

The attack also damaged other areas of the refinery. Site 5 appears to be the hub for transferring oil products onto rail transport, and it suffered substantial damage to buildings and pipework. Site 6 is an electricity substation, where a building housing electrical equipment suffered significant damage.

Figure 3: Destruction across the six sites as visible in satellite imagery.

Purported footage of the attack was played on Russian television during a press briefing by Lieutenant General Igor Knoshenkov. However, there is far too much snow on the ground for this to be footage of the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery on 02 April 2022. Weather records indicate that the last time that the temperature in Kremenchuk had fallen below freezing prior to the attack was on 08 March 2022. This means that over three weeks had passed between the latest freezing temperatures and the attack, making it unlikely that any snow would be present on the ground at all. Footage posted to Ukrainian Telegram channels from around Kremenchuk following the attack does not show any snow on the ground. Furthermore, the video could not be geolocated to the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery. These factors may indicate that footage of a different attack was used, creating a false impression that the narrative and the video are of the same attack.

Munitions used

Given that Kremenchuk is located deep inside Ukrainian territory during this attack, and well out of range of conventional and rocket artillery, the types of weapons systems that could reach it are limited to long-range missiles, or projectiles launched by aircraft.

This is consistent with claims made by the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation: “This morning land and sea-based long range precision weapons were used to destroy storage tanks with gasoline and diesel at the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery…” However, Ukrainian reports on the incident are unclear, with early comments by Dmytro Lunin indicating that “three aircraft” were responsible for the attacks, while later comments simply stated that it was “bombarded” without indicating a weapon system. Ultimately, as a result of limited imagery of the munitions used, their remnants, or their delivery method, Ukrainian Archive is unable to confirm the type of munition used or its delivery method.

5. Consequences of the damage

Victims of the attacks

There are no reported fatalities directly resulting from the strikes on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery. In a Telegram post on 05 April 2022 Dmytro Lunin, reported that “several” people had suffered burns and were in hospital with non life-threatening injuries.

Environmental damage

The attack at Kremenchuk has led to potentially significant environmental consequences. As a result, there were immediate discharges of pollution into the atmosphere and onto soils, with the potential for the longer-term migration of pollutants into surface and ground waters. These can have short-term and long-term health impacts to those exposed, be that via direct inhalation of smoke or ingestion of contaminated crops. More civilians are also at risk of exposure given the population of Kremenchuk is reported to have increased by a third due to the influx of internally displaced people from other more vulnerable regions of Ukraine.

The large fires and burning of petroleum emit greenhouse gases and short-lived climate forcers, like black carbon. Indeed the climate impact may be quite complex, with emissions from the out-of-service refinery instead displaced, or novel sources of emissions such as SF6 from damaged switchgears.

The emergency response was not one that would occur in peacetime. There is most likely an investigation into these attacks by the Prosecutor General’s Office, however due to the severe lack of capacity of the domestic authorities to ensure quality investigations due to the ongoing active conflict, it is very difficult to assess whether the investigation is being conducted in line with international standards, and includes all the steps that needed to be taken in order to measure effectively and efficiently the extent of the damage. This is a major obstacle to understanding the health risks of exposures. The emergency response may even have contributed to pollution, for example from the use of firefighting foams which contain PFAS “forever chemicals”, or still-harmful alternatives.

The attacks have also led to considerable waste and debris. This waste can be a secondary pollution source, containing hazardous materials like asbestos. The proper treatment of this debris is a challenge given pressure on solid waste management in the city. There is a risk that if improperly managed it may lead to a displacement of the contamination.

In subsequent reports on the attacks at Kremenchuk Oil Refinery we will take a deeper dive into other environmental issues. The focus of this report is the air pollution as a result of the attack.

Air pollution

The primary environmental impact in the short-term was due to the significant smoke plumes generated by the multiple plumes at different facilities. The smoke will have contained very high concentrations of particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides (NOx), nitrous acid (HONO), carbon monoxide (CO), sulphur dioxide (SO2), volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as formaldehyde, and potentially dioxins, furans, hydrocarbons and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

There are no publicly available data on the composition of the smoke plumes – unlike during the response to such fires in non-war situations in Ukraine,1 and elsewhere2 – and so the exact composition of the smoke remains unknown. Furthermore, without knowing the contents of the storage tanks set alight, it is not possible to speculate on the more trace constituents with specific toxicologies. Visually, the plumes were particularly dark, meaning the particulate matter likely had a high fraction of black carbon, a very unhealthy and climate relevant aerosol.

We do know that the substation was damaged, and this may pose a significant toxicology risk. The oil used as an insulator in transformers and capacitors may include Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs),3 one of the most dangerous persistent organic pollutants which bioaccumulate and are highly toxic. If there was also a fire at the substation, the environmental risk is even higher – PCBs break down into the more toxic dibenzofurans and dibenzodioxins.

The prevailing wind on the 02 April transported the plume to the north, fortunately sparing direct exposure to tens of thousands in Kremenchuk city, though it is likely many in the small rural villages inhaled the smoke. The duration of the fire is not known – clouds prevented good tracking from space – and it is possible that smouldering or underground burning continued for days. Modelling of the smoke plumes will be an important step to identify where pollutants may have been deposited – this is another important pathway of pollution, as identified after the Milazzo refinery fire in Italy. There are particular food safety risks if, as is likely, much of the deposition occurred on cropland to the north of the refinery. Deposited pollution can lead to a secondary emission of air pollution at a later date, through resuspension or soil-air exchange.

Potential responsibility

There are three principal factors which indicate that the Russian Federation is responsible for this attack. The first is that the Russian Ministry of Defense took responsibility for the attack. The second is that Ukraine had no reason to bombard its own last remaining oil refinery. The third is that the armed forces of the Russian Federation are the only party in this conflict that had the capability to carry out such an attack on 02 April 2022. When Russia launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, marking a drastic escalation of the armed conflict which began in 2014, Ukraine allegedly had very few long-range missiles and was likely using them sparingly. It was not until the delivery of the US-produced HIMARS rockets and launchers that Ukraine was able to launch long-range missiles in the quantities seen in the 02 April 2022 attack on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery. However, this delivery took place in the late spring and summer of 2022, months after the 02 April attack.

6. Special focus: The legal framework

Despite the increasingly well understood destructiveness of war, international law remains insufficiently protective of the environment. It was only after the horrendous experiences of the Vietnam War that treaty law began to be developed. First on the use of the environment as a weapon of war, and then as part of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (API); for more historical background, see UNEP report, page 12, but its provisions governing the protection of the environment during armed conflicts remain ineffective.

This note explores the parallel international regimes governing the actions of Russian soldiers in respect to the war in Ukraine. Using the example of the attacks on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery, it will show the shortcomings of international law in protecting the environment from the damage during excesses of war.

International humanitarian law

The primary legal regime governing all wartime activities is international humanitarian law, and API contains provisions governing harm to the environment.

Article 35(3) API codifies a prohibition of the use of means and methods of warfare that may be expected to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the environment. Similarly, Article 55(1) API establishes an obligation to take care during warfare to prevent such damage, and Article 55(2) prohibits attacks against the environment by way of reprisals. These standards have been interpreted by the International Committee for the Red Cross (ICRC) in its 2020 Guidelines on the Protection of the Natural Environment in Armed Conflict.

While these provisions would appear to create strong regulations governing a wide range of environmental harms arising out of war, the cumulative threshold for their application – that the environmental harm is widespread and long-term and severe – are extremely difficult to satisfy. In order for harm to be widespread it must span several hundred square kilometers, according to the understandings of the ENMOD Convention prepared by the parties (1976 Report of the Conference of the Committee on Disarmament, page 97), although some commentators suggest damage should span thousands of square kilometers (Peterson). In order for it to be long-term it should last several years according to the ENMOD Convention understandings, although the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) interpreting Article 35(3) API instead considered a scale of decades more appropriate (Final Report on NATO, para 15). Finally, in order for damage to be severe it must have serious environmental impacts going well beyond ordinary battlefield damage as considered by the parties drafting Article 35(3) API (Gillett, page 102). Given the huge levels of environmental destruction that can occur during battlefield damage, this sets a very high threshold covering only the most exceptional cases of damage, as suggested by the ICTY (Final Report on NATO, para 21). A final factor that makes this standard difficult to apply is that it does not correspond to the nature of environmental destruction during armed conflict. Destruction of this type is often cumulative, amassing over the full length of the armed conflict, whereas the prohibition in Article 35(3) API appears to apply only to individual means or methods of warfare.

Beyond these provisions specifically governing the protection of the environment during armed conflict, the general principles of International Humanitarian Law also continue to apply and impose limitations on the actions of all parties to the conflict. These include the principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution, as well as the principle of military necessity (for more information, see ICRC Guidelines, page 47-62).

Another provision of international humanitarian law that may be applicable to the attacks on the oil refinery is Article 56(1) API, which prohibits attacks on works or installations containing dangerous forces, where they may cause severe losses among the civilian population. The provisions list examples such as dams and nuclear power stations, but this may include oil refineries given the possibility of explosions and wide-ranging human and ecological damage (as supported by the ICRC, para 162). Even if it does apply to the refinery case, it should be emphasised that this provision is not an environmental one, and any environmental effects would be legally irrelevant for the purposes of liability.

International criminal law

Only one provision of the Rome Statute refers explicitly to harm to the environment. Article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Rome Statute codifies a war crime of launching an attack that creates widespread, long-term and severe damage to the environment that clearly exceeds the concrete and direct overall military advantage of such an attack. There are three reasons why this crime is incredibly difficult to evidence.

First, since the qualitative elements of this standard – “widespread, long-term and severe” – are cumulative and likely to be interpreted in accordance with 35(3) API, they set a very high threshold for culpable harm. Second, an additional complication is that in the context of international criminal law, the widespread, long-term and severe damage – as well as the knowledge of the perpetrators that such harm would arise – will have to be proven beyond reasonable doubt. Lastly, the provision further weakens environmental protection by allowing perpetrators to justify the environmental damage using the vague notion of “concrete and direct overall military advantage.”

These deficiencies in Article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Rome Statute, as well as the fact that it only applies to international armed conflicts, has led to renewed calls to introduce a new crime of ‘ecocide’, i.e. wanton destruction of the environment. In 2021, an independent panel of experts drafted a new provision for the Rome Statute that would prohibit severe and widespread or long-term damage to the environment. Interestingly, both Russian and Ukrainian law already contain a specific crime of ecocide. While there are obviously no efforts by Russia to end impunity for crimes committed by its soldiers, the Ukrainian Office of the Prosecutor General has launched several investigations into potential acts of ecocide arising out of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It remains to be seen what impact the renewed attention to environmental crimes will have at the international level. As at the domestic level, the effectiveness of environmental crime prosecutions is not only a matter of substantive law, but also highly contingent on case selection and prioritization.

International human rights law

International human rights law continues to apply during armed conflicts, and there is growing acceptance of a human right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, as evidenced by a UN General Assembly resolution and UN Human Rights Council resolution 48/13. This right requires states to take positive steps to protect the environment.

While it is highly controversial to what extent the right to a healthy environment is currently binding law limiting the actions of states like Russia, the emergence of human rights should be understood as a dynamic process in which previously unrecognized rights can grow into full binding effect through the practice and recognition of states. Insofar as Russia’s military operations are taking place on the territory of Ukraine, it should be noted that, although human rights are traditionally considered to apply primarily only on the territory of the respective state, there is increasing recognition of their extraterritorial applicability, at least in situations where states exercise effective control over the territory of a third country. However, where human rights are applicable extraterritorially in the context of armed conflict, they are usually applied to a lesser extent. For example, the right to life continues to apply during armed conflict, but it generally only prohibits killings that are not compliant with international humanitarian law. Analogising with the right to a healthy environment, this may be interpreted by human rights courts as only requiring the degree of protection of the environment mandated by international humanitarian law, discussed above. In this respect, international human rights law runs the risk of being as permissive of conflict-related environmental destruction as international humanitarian law.

International environmental law

Finally, international environmental law also continues to apply during armed conflicts.

In respect of treaty law, Russian armed forces are subject to the Paris Agreement, which has as its aim halting the rise in average global temperature. War undoubtedly releases greenhouse gases. The Initiative on GHG Accounting in War estimates that 120 million tonnes of CO2 were released from conflict-linked sources during the first year of the war. However, the Paris Agreement favours procedural over substantive obligations in reaching its goal. Article 4 merely requires Russia to prepare and submit nationally determined contributions outlining its emissions reductions targets, and does not require Russia to assess its harmful environmental activities extraterritorially in the war in Ukraine.

Turning to customary international environmental law, all states are under an obligation to abide by the precautionary principle when engaging in activities causing large scale environmental impacts. This requires exercising caution and taking prior steps before engaging in the potentially polluting activity, such as carrying out environmental impact assessments. This has not been applied to the context of war, and it may be considered that a more specific version of the precautionary principle is codified in Article 55(1) API, which requires belligerent states to take care to protect the environment from widespread, long-term and severe damage to the environment. How these principles interact may require some clarification.

A final source of obligations applicable to the Ukraine war is in the principles on the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts drafted by the International Law Commission (which have been analysed by the Conflict and Environment Observatory). While its provisions may constitute a mixture of binding and non-binding law, best practice, progressive development and evolutive interpretation, consensus may well emerge among states elevating all of its principles to binding rules that protect the environment. While these principles are wider ranging than current international environmental law or international humanitarian law, the general protection standard at principle 13 applies only to “widespread, long-term and severe damage” which, as explored above, is a flawed standard.

7. Conclusion

The analysis of the attack on the Kremenchuk Oil Refinery underscores the complexities of protecting the environment during armed conflict. Not only can the effects on the environment and the people which reside there be far-reaching, they are also difficult to accurately measure and predict. The mechanism for holding state perpetrators of environmental crimes accountable is sometimes insufficient for bringing about reparations for victims. Under the current legal and political circumstances, obtaining reparations for damage done to the Ukrainian environment will be challenging.

- At a fuel depot. near Kalynivka Airfield there was a major 12-day fire in 2015. This received a massive emergency response that prevented the fire spreading to the nearby military depot. The fire received international attention, locals were evacuated, air pollution was monitored, and there were environmental assessments after the incident.

- The most well characterised analogous case is the 2005 Buncefield oil depot fire in the UK. Jaume Targa et al., (2006) and Mather et al., (2007) present the measurements of the Buncefield smoke plume taken from ground, air and satellite. There was also a suite of measurements and exposure modelling following a fire at a petrochemical complex in central Taiwan – see Shie and Chan (2013).

- Though PCBs have been phased out elsewhere, due to their environmental impact, they are reported to be still in significant use in Ukraine