Mapping Ukraine’s ecologically important areas

Published: October, 2023 · Categories: Publications, Ukraine

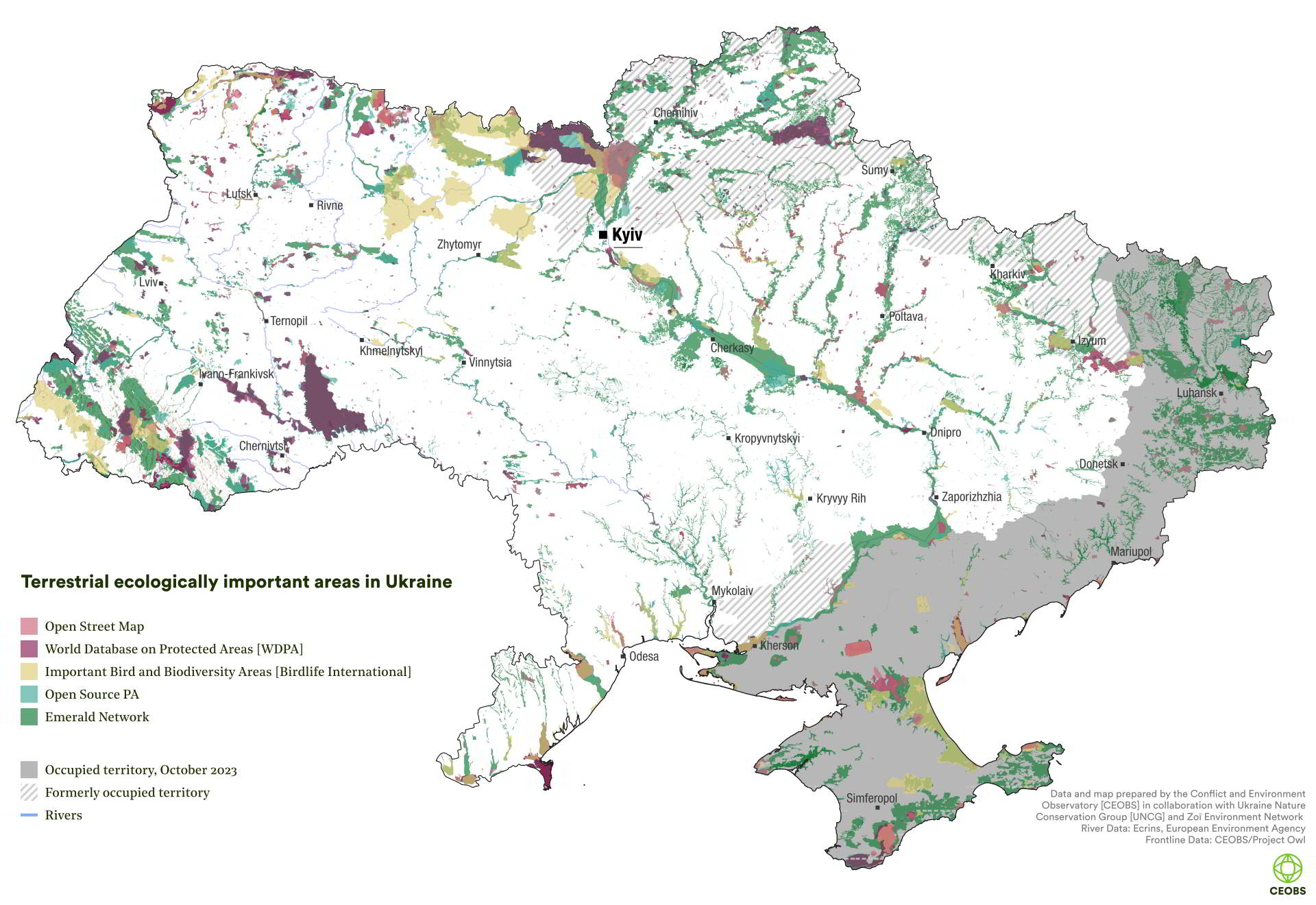

The war has disrupted efforts to digitally map Ukraine’s ecologically important areas, while making it more vital than ever that we understand where they are, and how they have been impacted. With support from the UN Environment Programme we have worked with the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group and Zoï Environment Network to build what we believe is the most comprehensive digital map available of Ukraine most important areas for nature.

Contents

Context

Area-based conservation is increasingly recognised as important for delivering sustainability goals and tackling biodiversity loss. It can include the designation and legal recognition of geographically defined areas, creating protected areas (PAs). But it also applies to any other areas that may be governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity. In many cases, their rationale is also to protect ecosystem services, and an area’s cultural value. In this post we use the term ecologically important areas as a general term that includes both PAs and important areas without formal legal designation.

The recently adopted Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, together with the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, called for at least 30% of the land and sea to be protected or restored to enhance biodiversity, as well as ecosystem functions and services, and ecological integrity and connectivity. However, consideration of the challenges that fragility and armed conflict create for ambitions like 30×30 is underdeveloped.

At present, many countries are far short of the 30×30 target, and Ukraine is no exception. The percentage of its territory that enjoys protection under defined national legislation increased from 4.6% in 2004, to 6.8% today; this is low by EU standards. This figure does not include the Emerald Network, a substantial area of prospective PAs approved by the Council of Europe as part of the Bern Convention. Ukraine has ratified the convention and is in the process of creating Emerald Network sites but it has not yet adopted the national legislation and by-laws necessary to implement it fully.

The figure also excludes Ramsar sites and UNESCO biosphere reserves, as well as Environmental Network sites, some of which partly overlap with its PA network. Collectively, these sites have the potential to significantly increase the area of Ukraine’s legally protected sites. For Ukraine to meet its international obligations, it is critical that its PA coverage continues to be expanded, and that more effective conservation measures are put in place. It is also critically important to understand how its existing network has been affected by conflict with Russia.

Biodiversity under attack

War can be a major driver of environmental degradation, and of biodiversity and ecosystem loss, in turn harming communities dependent on their ecosystem services. Around 35% of Europe’s biodiversity is thought to be represented in Ukraine. Even before February 2022’s full-scale invasion, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and occupation of parts of the Donbas, had heavily impacted biodiversity protection. Ukraine was no longer able to exert control over some of its most important PAs. In Crimea alone, this included six out of Ukraine’s 19 nature reserves – those designated as IUCN 1A. Nationally, around 2,000 nature conservation areas have been either temporarily occupied, or remain occupied.

Since February 2022, hundreds of Ukraine’s PAs have suffered direct and indirect damage. PAs have been occupied, or crossed by front lines, with park offices and infrastructure destroyed, and equipment looted. Landscapes have been affected by fire, or rendered inaccessible by the presence of unexploded ordnance. Efforts to understand the scale of the damage wrought by the war are ongoing, involving the Ukrainian authorities, domestic experts and international organisations.

Mapping Ukraine’s biodiversity

As with all countries pursuing area based conservation measures, meaningful protection requires going beyond national level legislation and plans, and supporting local implementation, whether through by-laws or through the provision of resources and capacity. In the years leading up to 2011, Ukraine had seen a consistent increase in its network of conservation areas.

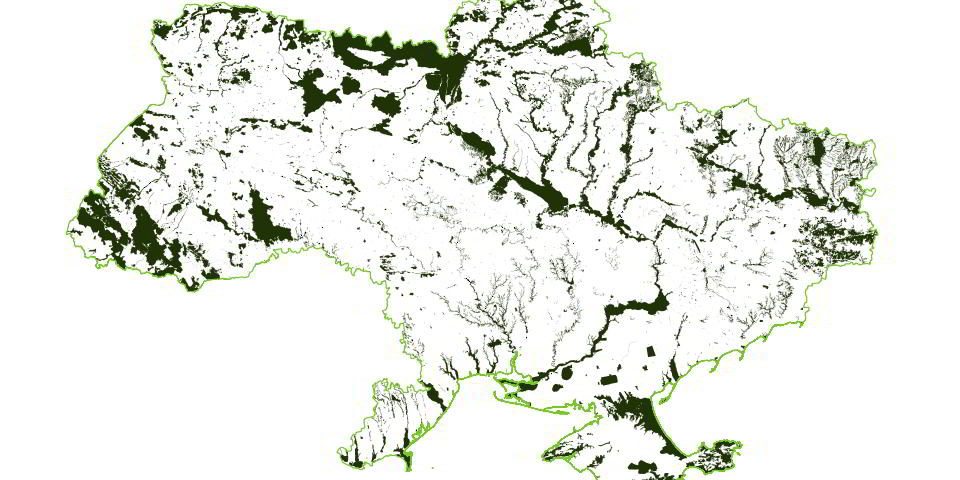

While some work had been undertaken to map its PA network during the 1970s and 1980s, economic and governance issues prevented its completion. Since 2014, volunteers from the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group (UNCG) have worked unfunded to collate map data from a wide range of open sources. They were not the only organisation to be involved in mapping, for example, the Society for Conservation GIS Ukraine also created maps, uploading these to the Open Street Map (OSM) platform, which the UNCG has supplemented. More recently, some efforts to gather data on the locations and boundaries of ecologically important sites have been included in a German-backed technical assistance programme aimed at strengthening Ukraine’s PA governance. However, the Russian invasion disrupted this work, impeding the process even as it increased the range of threats faced by Ukraine’s ecosystems.

Digital maps are vital tools for area-based conservation, allowing the survey and analysis of biological and socio-economic data. Because of this, we decided to work with UNCG experts, and colleagues from Zoï Environment Network, to create a digital map of designated PAs and other ecologically important areas in Ukraine. The project was funded by the UN Environment Programme.

Method and results

What we have mapped

While there are many areas and natural monuments that have protected status in Ukraine, there are also many prospective sites of interest to conservationists, as well as ecologically important areas identified by researchers, which are currently unprotected. We wanted to capture as many of these as possible.

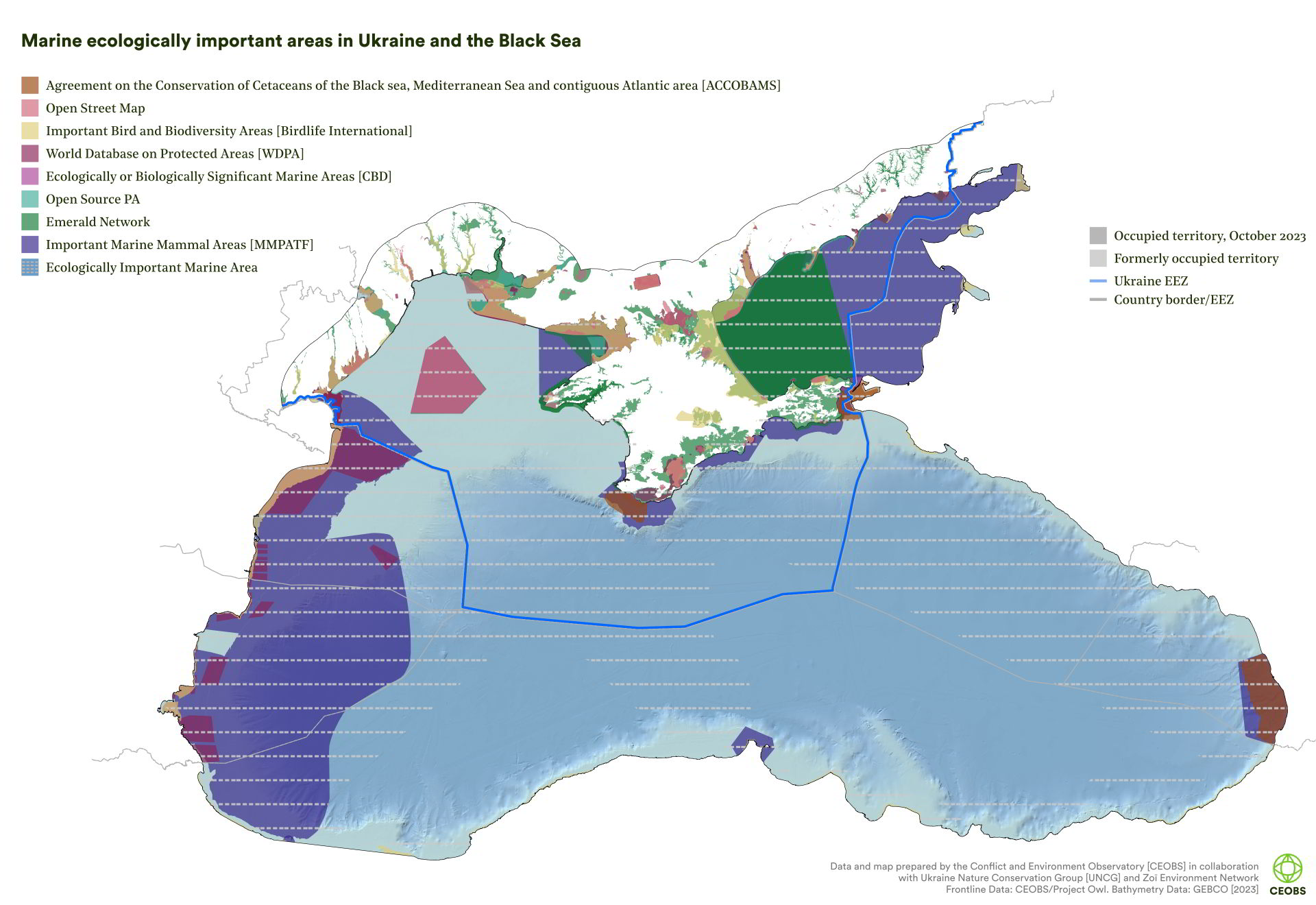

The map we have developed consists of nine data layers, as shown in Table 1 below. PAs captured in the UA OPEN SOURCE PA layer are legally recognised PAs, with the boundaries estimated through the UNCG’s open source research. It is not based on official government data but on the UNCG’s own research, which has supplemented the work also undertaken by the Society for Conservation GIS Ukraine. The World Database of Protected Areas (WDPA) and to some extent the OSM layers also typically contain PAs with some degree of official status under national or international legislation. The number of ecologically important areas varies between the files, the most extensive list is captured in the UA OPEN SOURCE PA file, and includes 7,842 PAs, whereas ACCOBAMS with three areas contains the fewest. Our methodology can be found at the end of this post.

| Name | Definition | Curated by | Number of sites in file | Legal recognition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA OPEN SOURCE PA | Discrete areas that provide important services to one or more species/populations or an ecosystem; covers different categories of PAs. | National experts. | 7,842 | Yes |

| OSM | Open source database of marine and terrestrial PAs available through Open Street Map (OSM). | National experts. | No data | Legally recognised sites but boundaries uncertain. |

| WDPA | Open source global database of marine and terrestrial protected areas, including Ramsar and Natura 2000 sites. | National and international experts. | 1,358 | Yes |

| Emerald | Network of areas that protects species and habitats of the Bern Convention. | National and international experts. | c.500 | Convention ratified, domestic law in progress. |

| KAB | Important habitat areas for bird populations in Ukraine and the Black Sea. | National experts. | 185 | No |

| EIMA | Important habitat areas for marine animal populations in the Black Sea. | Observations, published data. | 3 | No |

| EBSA | Oceanographically discrete areas that provide important services to one or more species/populations of an ecosystem or to the ecosystem as a whole. | National and international experts. | 6 | No |

| IMMAs | Important Marine Mammal Areas are habitat areas important to marine mammal species. | National and international experts. | 11 | No |

| ACCOBAMS | Contain important areas to marine mammals, assessed by ACCOBAMS experts (Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black sea, Mediterranean Sea and contiguous Atlantic area). | ACCOBAMS experts. | 3 | No |

The number of areas that the map contains leads us to believe that it is the most comprehensive digital map currently available on Ukraine’s ecologically important areas. Nevertheless, it likely remains incomplete. For example, the UA OPEN SOURCE PA file available to us held information on around 7,842 sites, but the true number of PAs is likely to be higher. Ukraine’s Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources gives a slightly larger number of 8,844, although this is not based on a digital map. In theory, there might be many more, therefore it is important to bear in mind that new areas may be added to the map in the future.

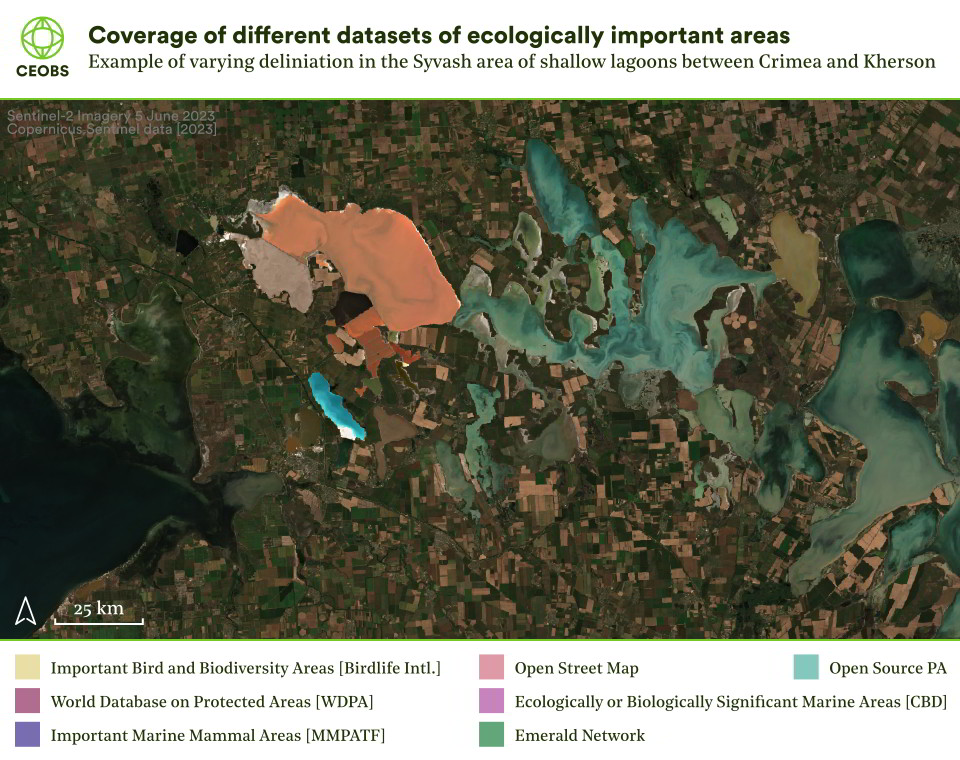

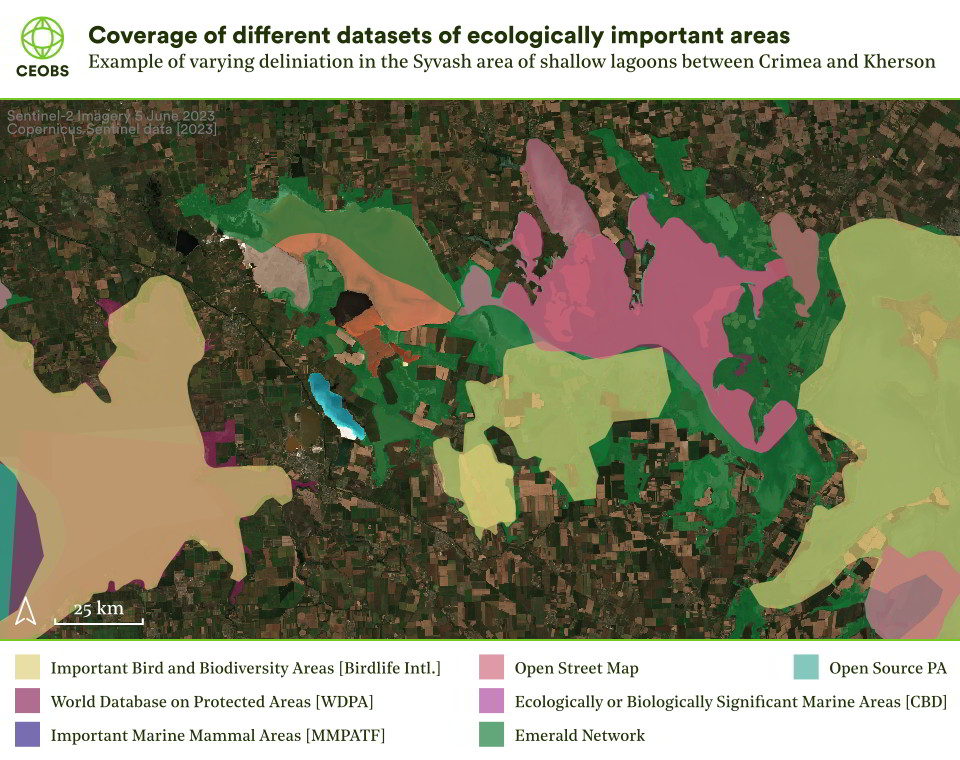

Another limitation concerns the boundaries of ecologically important areas. In some cases, the same areas appeared in more than one dataset and do not perfectly match. This is a result of ongoing mapping by national experts in Ukraine. Therefore it is also important to consider that in some cases, boundary representations might be flexible, and open to different interpretations.

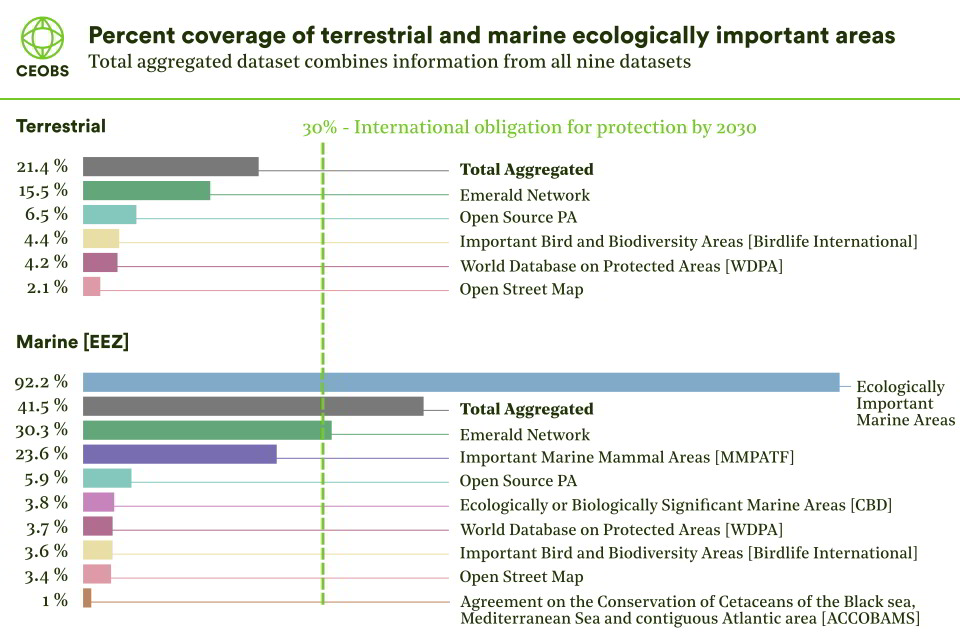

Comparing each layer by terrestrial or marine area covered demonstrates just how important the effective legislative protection of terrestrial and marine Emerald Network sites could be for Ukraine’s 30×30 obligations. Similarly, the fact that more than 90% of Ukraine’s Exclusive Economic Zone has been designated as an Ecologically Important Marine Area (EIMA) reveals the importance of Ukraine’s coastal shelf for key marine species of the Black Sea.

Open source data shows that Ukraine’s current PA coverage is 6.47% and 5.9% of Ukraine’s landmass and EEZ, respectively. Aggregating the combined datasets in our map finds that the prospective marine area coverage of Ukraine’s EEZ is 41.49%, while the prospective terrestrial area coverage of Ukraine’s landmass is 21.41%. This suggests that Ukraine is better placed to meet its 30×30 targets for marine, rather than terrestrial areas. However, this assumes that both its marine and terrestrial areas can be adequately protected and managed.

Applications and lessons learned

How will this data be used?

Since February 2022, CEOBS and Zoï Environment Network have been gathering and analysing data on environmentally harmful incidents in Ukraine. The data is being used to raise awareness, to inform assessment and remediation, and potentially for accountability purposes. The map of ecologically important areas will help us undertake a more systematic remote analysis of the future risks to ecologically important areas, and of any harms that have already been caused. A comprehensive map is particularly important because determining ecological harm on the basis of remote data alone is challenging, often requiring further validation by field assessment and local expertise.

Final thoughts

Armed conflicts and insecurity are recognised as an indirect driver of biodiversity loss by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Yet the recently adopted Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework was largely silent about the specific implementation needs of fragile and conflict-affected states. In the case of Ukraine, we have seen the consequences of high intensity armed conflict and technogenic disasters on marine and terrestrial PAs, as well as massive disruption to habitats and ecosystems.

Understanding harm and identifying opportunities, not just for restoring nature but also for fully integrating it into recovery, are contingent on data. Much of this will need to come from the ground, and from the Ukrainian experts best placed to collect and understand it. However, this project shows one way in which international actors can not only refine their remote analyses but also help support conservation experts in conflict-affected areas.

The finalisation of the International Law Commission’s PERAC principles has rekindled interest in a decades-old debate over whether and how sites of particular ecological interest could be designated as demilitarised or protected zones during armed conflicts. This project is a reminder that even in countries with relatively well-developed conservation programmes and PA architecture, there can be considerable uncertainty over the locations and boundaries of ecologically important areas, or data may not be readily accessible. These barriers could constrain efforts to identify or agree on sites, and it underscores the important role that projects of this type could play in such processes in future.

The mapping project was led by CEOBS’ Dr Linas Svolkinas, in collaboration with the UNCG’s Oleksiy Vasyliuk and Zoï Environment Network’s Dmytro Averin. The work was funded by the UN Environment Programme. Our thanks to Olesya Petrovych for her review.

Annex: Methodology

It should be noted that there is no single official map of all of Ukraine’s ecologically important areas. Therefore the information that we used to map protected and ecologically important areas was obtained from a wide range of different open sources.

The UA OPEN SOURCE PA layer contains data that the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group has collected from various open sources over many years, including through the creation of digital maps of PAs based on paper maps. These boundaries have been through their own internal verification process.

OSM polygons were extracted on 04/08/2023 using R coding.

We downloaded the April 2023 version of PAs from the WDPA database, clipping the data polygons to those located within Ukraine or the Black Sea. The WDPA data includes Ramsar UNESCO biosphere reserves, Natura 2000 sites (marine sites located outside the Ukrainian EEZ).

Our analysis showed that the list of Emerald Network sites in the WDPA database was incomplete. Because our compiled version consists of a more complete list of Emerald Network sites, and also to avoid duplication, we chose to retain the Emerald layer as an individual dataset and removed Emerald Network sites from the WDPA data.

We received additional data from BirdLife International, and the IUCN; IBAs and IMMAs respectively. The Ecologically and Biologically Significant Area (EBSAs) dataset was downloaded from the CBD’s homepage.

The EIMA data layer was developed using a range of open source information mapping Black sea species distribution (see table below). Maps downloaded from GRID Arendal’s webpage included habitat features of a range of species, and were drawn for the Black Sea Environmental Programme (BSEP). These included turbot, sturgeon (Acipenseridae) and anchovy (Engraulis Encrasicolus) spawning grounds; mussel beds, and the map “main spawning areas (all fishes)”, and the map on the reduction of Zernov’s Pyhyllaphora Field. Polygons were aggregated using unioned indexes, forming the EIMA layer. We chose to exclude the EIMA layer from the estimate of the aggregated value of marine areas, but retained all the other datasets.

Data on the Ukraine Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the polygon representing Ukraine’s boundaries were extracted from open sources.

Physical maps were digitised to polygon shapefiles using ArcMap. Individual polygons were merged into a single dataset and all features in the merged data set were indexed (using the union” command). EMODnet data available as point data was converted to polygon data shapefiles using ArcMap software cartography tools. Polygons were aggregated using unioned indexes, forming the EIMA layer. All layers in the dataset underwent multiple quality checks and reviews. We checked for any obvious errors and the attribute table between the data layers was synchronised. All spatial analysis, including performing the area to country clipping, polygon binding and union, polygon dissolving and merging, and the area coverage, was done using the “sf” and “sp” packages in R.

EIMA layer open data sources.

| Species/biota | Data type | Data description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zernov's Phyllophora Field | Polygon | The reduction of the Zernov’s Pyhyllaphora Field. | GRID - Arendal |

| Multiple | Polygon | Main spawning areas (all fishies). | GRID - Arendal |

| Sturgeon (multiple species) | Polygon | Sturgeon distribution in the Black Sea. | GRID - Arendal |

| European Anchovy (Engraulis Encrasicolus) | Polygon | Changes in the spawning grounds of anchovy. | GRID - Arendal |

| Turbot (Scophthalmus Maeoticus) | Polygon | Turbot distribution in the Black Sea. | GRID - Arendal |

| Mussel | Polygon | Mussel bank. | GRID - Arendal |

| Hexacoralia (multiple species) | Point | Species sightings. | EMODnet |

| Common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) | Point | Species sightings. | EMODnet |

| Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) | Point | Species sightings. | EMODnet |

| Harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) | Point | Species sightings. | EMODnet |