Without a comprehensive assessment, plans to address the Donbas’ environmental risks are of limited value.

With the threats that the Ukraine conflict poses to the environment once again in the news, Zoï Environment Network has released new maps on the environmental consequences of the conflict. With both sides increasingly conscious of the humanitarian and ecological impact of the war, plans to minimise risks and encourage sustainable reconstruction are being promoted. However, without a comprehensive assessment of the damage, such proposals are of limited value. This blog reviews Zoï’s latest research and argues that absent a UN-led assessment, civil society should be encouraged to plug the assessment gap.

Context

The recent upsurge in violence in the conflict in eastern Ukraine has once again focused attention on the serious risk that the fighting between Ukrainian government forces and separatists – in particular the use of heavy weapons around industrial facilities – could trigger serious environmental and humanitarian consequences. The Donbas region is replete with industrial risks, a legacy of its 200 year history of coal mining and heavy industry, and the threats that this legacy pose have helped frame the conflict’s environmental narrative.

Speaking at the UN Security Council in February, the head of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) warned that:

“If hostilities continue, we may also be faced with a serious environmental crisis. Damage to the Phenol plant near Novgorodske village means that waste chemicals, including deadly sulfuric acid and formaldehyde, are now at critical levels. Leakage into the surrounding land and the Seversky Donets River would have disastrous humanitarian consequences in a highly industrialized part of Europe. Similarly, there is a real risk at present that damage to water facilities could have further deadly consequences for the population living in the surrounding areas, with the potential leak of chlorine gas which is routinely stored at such facilities”.

February’s renewed focus on the threat of environmental emergencies triggered by the release of industrial chemicals appeared to encourage the authorities of the separatist-controlled parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts to issue a joint statement. The statement demanded, among other things, access to critical industrial and municipal facilities on the Ukrainian-controlled side of the line of contact in order to verify their environmental safety. The statement also announced a new “Humanitarian programme for the Reunification of the Donbass People”. Elements of the programme envisage quarterly activities aimed at the restoration, maintenance and protection of at-risk industrial facilities, proposals to prevent or reduce the environmental consequences of their damage or disruption and, perhaps optimistically, joint inspection visits.

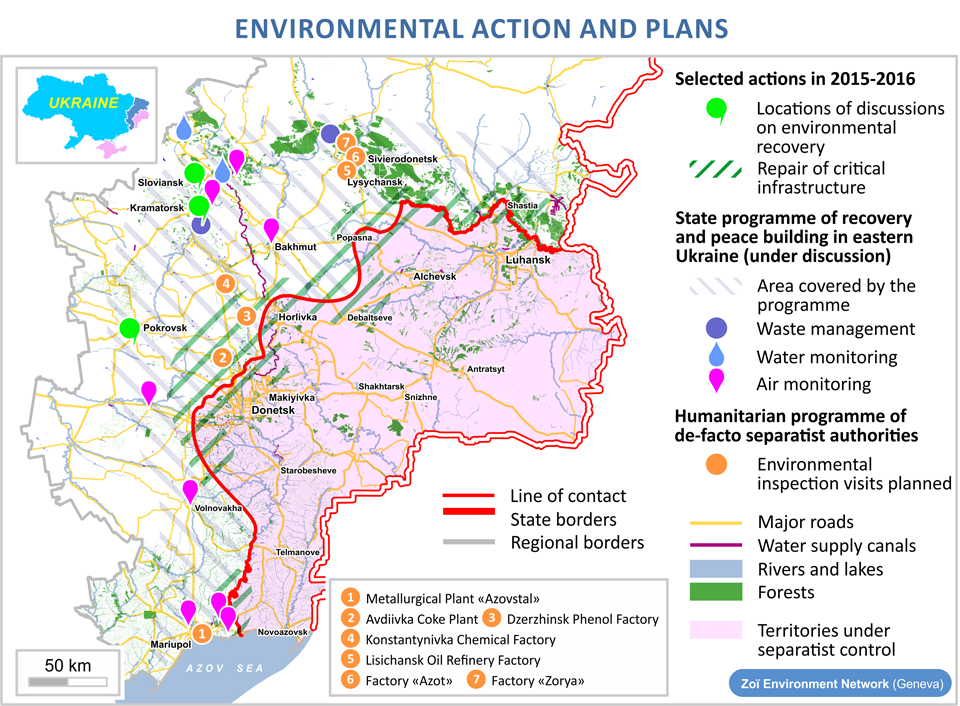

Prior to the recent upsurge in violence, the Ukrainian authorities had also announced new initiatives on the environment. Late last year, the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources stated that it had begun satellite monitoring of damage to natural resources and the environment in Crimea and the Donbas region, for the purposes of one day supporting international litigation. Meanwhile in December, the Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and Internally Displaced Persons presented a draft plan for a “State-run programme of recovery and peacebuilding in eastern Ukraine”. The plan contains several environmental elements, including a damage assessment, but has been criticised for its optimistic reconstruction plans, which have been presented on the basis of limited environmental data.

Last year, the UNDP also proposed a regional development strategy for the Donetsk region. However these plans, which extend out to 2020, have also drawn criticism. This time for their focus on sustaining the region’s economic model of reliance on heavy and polluting industries, rather than proposing more innovative reconstruction based on cleaner technologies and diversification.

The state of the Donbas region’s environment

In spite of the tentative signs of interest in the environmental consequences of the conflict, which is now entering its fourth year, as yet there has been no comprehensive assessment of the damage wrought thus far. However, the Geneva-based Zoï Environment Network, which worked on environmental issues in Ukraine prior to the outbreak of hostilities, has sought to collate data on environmental damage and threats, both from online sources and from its partners on both sides of the line of contact. Together with the Toxic Remnants of War Project, in May 2015 Zoï published an initial snapshot of environmentally harmful incidents and practices. The study not only highlighted the damage to industrial infrastructure but also impacts on air quality, groundwater pollution from flooded mines, damage to water supplies and to forests and protected areas. Zoï’s findings have now been updated and help to identify issues that should be included as part of a more formalised assessment.

Damage and disruption to industrial facilities

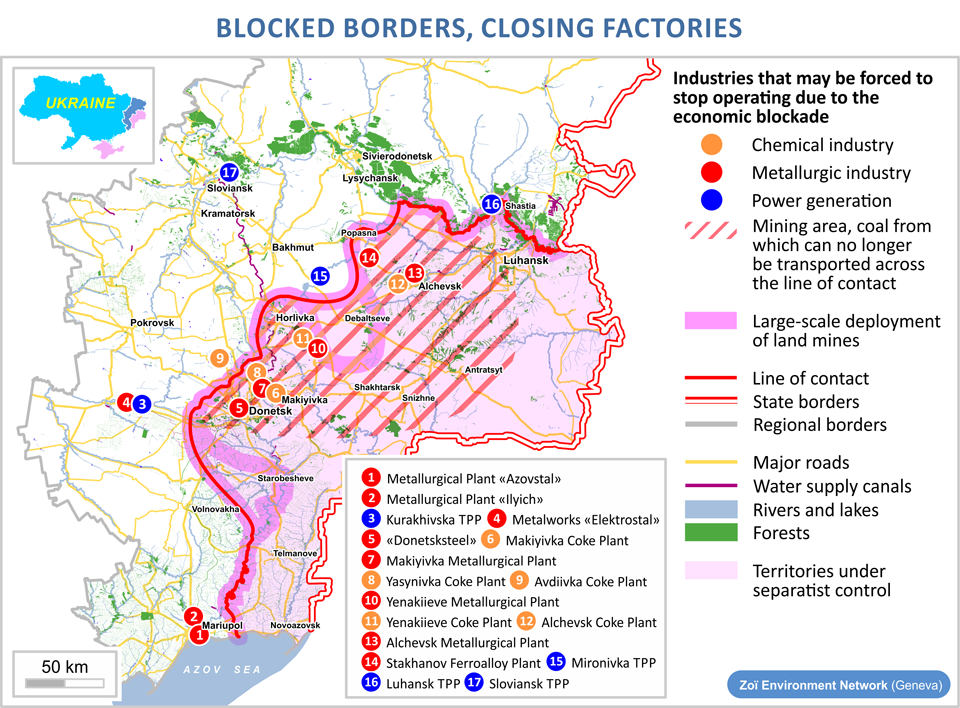

Three factors have mediated the ongoing environmental risks from the region’s industrial sites; the first relates to where armed confrontations take place; where the use of explosive weapons risks damage to facilities and where operations may be interrupted by fighting. The second is an unfolding “trade blockade” on the transport of goods and supplies across the line of contact, which is being organised by veterans of volunteer battalions from the Ukraine-controlled side. The third is access to electricity. It should also be noted that many of the region’s industrial facilities are in close proximity to urban areas.

In spite of repair work taking place during 2016, the fighting has continued to disrupt electricity and gas supplies, with knock-on effects on communities, on industrial production and with it the risk of environmental emergencies triggered by emergency shutdowns. For example, in 2015 a direct hit on the Kramatorsk-Donetsk-Mariupil gas pipeline almost stalled Mariupil’s metallurgy plants. More recently, fighting around the town of Avdiivka, which peaked in early February, almost halted the operation of its coking plant, which also provided the community with heating.

While shelling and the use of heavy weapons has continued, the trade blockade is also set to impact sites beyond the line of contact, inflicting shutdowns on a number of industrial facilities by interrupting supplies of raw materials. For industries in areas under government control, the blockade will halt the movement of coke-coal, anthracite and metal castings to the chemical, metallurgical and power industries, and block Ukrainian market access to mines producing coal in separatist-held areas. Meanwhile, iron ore imports to the separatist areas will also be halted. The reduction in industrial output may have positive short-term effects on air quality but severe impacts on the regions economy.

Effective from the beginning of March 2017, the de-facto authorities in the separatist areas have declared the nationalisation of the remaining industrial assets owned by Ukrainian businesses on their territory. The economic damage being caused to the region’s economy from the blockade is adding to that already caused by the uncontrolled dismantling of a number of industrial facilities in separatist-controlled areas. This process has been ongoing since the beginning of the conflict, with components exported for scrap or resale.

Vital industries and utilities continued to come under fire throughout 2016. A series of explosions have been observed at the Donetsk State Factory of Chemical Products (the latest as recently as February 2017), which were reportedly related to both shelling and to the inadequate handling of munitions within the factory itself. Recent attacks have again highlighted the risk that waste chemicals stored in numerous tailing ponds along the line of contact may find their way into surrounding soils and rivers. For the Dzerzhinsk phenol plant this could amount to some 400,000 cubic metres of waste chemicals, sulphuric acid and formaldehyde.

Disruption to water, power and municipal services

The Donetsk water filtration station has been hit by explosive weapons on numerous occasions. In addition to interrupting the supply of water to communities on both sides of the line of contact, any largescale release of chlorine and other hazardous chemicals stored at the site could potentially threaten the health of 20,000 nearby residents. Water supplies have been disrupted regularly, for example in mid-2016 thousands of people were deprived access to water supplies in the Berezove – Dokuchaevsk area. In addition to the disruption to water supplies, harsh living conditions and limited access to healthcare have been exacerbated by the deterioration of municipal waste management, leading to the uncontrolled accumulation of household waste and a rapid growth in the rodent population.

Zoï’s 2015 assessment highlighted the threat that the loss of electricity to the area’s coal mines posed to communities and the environment when the mines’ water pumps ceased working. While operations at some mines in separatist-held areas restarted in the relative calm of 2016, many others remain abandoned or their equipment demolished. The blockade may yet cause operations to cease once again. Rising water levels in the mines forces methane to the surface and into the basements of properties, while contaminated water from the mines can disperse into the surrounding groundwater, not only affecting the region’s water supplies but potentially also the Sea of Azov. Pollution from mines may be widespread and serious but its current extent and risks to environmental and human health remain poorly documented. It is not just the coal mines themselves that pose health and environmental risks; the fighting also has the potential to cause fires on the numerous spoil heaps from mines.

Damage to agricultural land and protected areas

The environmental hazards in the Donbas region are not restricted to pollution from industrial sources. Agricultural waste is also a threat. In the middle of 2016, the waste storage ponds of the Bakhmut agricultural cooperative began to leak slurry from pig farms after the maintenance of the ponds, which are located within a contested area along the line of contact, became impossible. The local population was advised to stop using water from the Kodemka River, which feeds into the Severskyi Donets, the main source of the Donbas region’s water supply. The risk of accidental damage to the waste storage ponds from renewed fighting was emphasised again earlier this year.

Although there was a period of relative stability between 2015 and 2016, this also allowed both sides to reinforce the line of contact with land mines; more recently the OSCE has reported that IEDs have also begun to be used. Mines have reportedly been placed on agricultural land, in nature reserves and on roads and bridges. Areas adjacent to the line of contact have also been heavily contaminated with UXO.

Since 2015’s report, forests have continued to be felled for fuel and fortification. Forest fires and the physical effects of the fighting – heavy weapons and vehicle movements and the digging of trenches and berms – have also taken their toll. Further damage has been documented in nature reserves and in forest protection strips, which were initially planted during Soviet times to protect the soils of agricultural land from the frequent dry winds. The fighting and the destruction of forests have also caused the migration of wildlife away from the conflict area.

International and Ukrainian response to environmental threats

Since 2015, when the environmental consequences of a conflict in such a heavily industrialised region were first becoming apparent, the Ukrainian government has repeatedly raised the issue at the UN level. In September 2015 at the UN General Assembly; at the Paris climate change conference; and in December 2015 through the tabling of a resolution on the Protection of the environment in areas affected by armed conflict, ahead of May 2016’s meeting of the UN Environment Assembly. The resolution eventually passed by consensus after months of difficult negotiations, although as tradition dictates, it did not specifically address the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Last month, the conflict was the pretext for an open debate in the UN Security Council, addressing “threats to international peace and security resulting from terrorist acts against critical infrastructure”. More recently, Ukraine raised the environmental situation in the region at UNEP’s Committee of Permanent Representatives; while last week, the UN Human Rights Council’s Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights warned that: “Battles are now being fought in cities, close to industrial centres, with factories increasingly becoming at risk of being hit: the consequences for anyone living close-by would be severe”.

On a regional level, in 2016, environmental concerns featured in the discussions of the OSCE-facilitated trilateral contact group on Ukraine, with its economic subgroup discussing the environmental risks from the flooding of the region’s coal mines. The OSCE also organised a series of “Reconstruction through dialogue” meetings under the umbrella of the East Ukrainian Forum, in 2015 and 2016, one of which explicitly addressed the environment. Other multi-stakeholder meetings were held in 2015; on the chances of sustainable development and reconstruction by the All-Ukrainian Ecological League; and on environmental monitoring in the Donetsk region by the East-Ukraine Environmental Institute and Ukraine’s Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources.

However, in spite of this initial interest, and with the exception of the limited environmental section in 2015’s World Bank-EU-UN recovery and peacebuilding assessment, no comprehensive information has been collected since to guide the assessment and mitigation of environmental damage from the conflict. The OSCE Special Monitoring Mission to Ukraine did undertake an assessment in 2015 but this was restricted to water facilities. As noted above, Ukraine’s Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources announced that it was gathering data on environmental harms in late 2016 but this has been complicated by the lack of access to territory not under government control.

What emergency assistance funding that has been made available from international donors for environmental work thus far has focused on critical water and sanitation infrastructure, although a few countries have provided modest resources for Ukrainian NGOs working on specific environmental issues linked to the conflict. It should be noted that the humanitarian response efforts as a whole remain underfunded.

Conclusion

The focus on the ongoing threat of environmental emergencies triggered by damage to the Donbas region’s numerous industrial facilities, and the disruption to water and other essential services have helped frame the conflict’s environmental narrative to date. However these problems represent just a fraction of a large and complex suite of environmental issues that will threaten sustainable recovery and development for years to come. Many of these were already present prior to the outbreak of hostilities but have been exacerbated further by the fighting.

While the action and recovery plans proposed by international organisations, and the Ukrainian and separatist authorities, are a welcome sign of renewed attention on the numerous environmental consequences of the conflict, all are bedevilled by the absence of a comprehensive assessment of the state of the region’s environment. The absence of such an assessment reflects a wider problem with how the international community currently documents environmental harm during conflicts, and in their immediate aftermath. The ongoing insecurity, complex politics and limited donor attention are all conspiring to limit the likelihood of a UN-led assessment any time soon. Meanwhile many of the problems documented above, for example groundwater pollution from mines, are likely to worsen without attention, and may have lasting consequences for water supplies and public health. It is vital that efforts are made to get a handle on the scope of these problems but it seems inevitable that doing so will require that civil society organisations help fill this documentation gap. This is not a situation that is unique to Ukraine.

Beyond the necessity of documenting the threats the conflict is posing to the environment, and by extension to communities on both side of the line of contact, robust and transparent environmental data could also be used to encourage communication and dialogue between the warring parties. Both the Ukrainian and separatist authorities have recently expressed an interest in the environmental consequences of the conflict, and greater environmental awareness could help reduce the threat of catastrophic industrial emergencies. While navigating the politics and modalities of a discussion on the environment will be challenging, the fact that these threats have little respect for frontlines or artificial boundaries could yet provide a foundation for community level talks.

Blog prepared by Nickolai Denisov and Dmytro Averin of Zoï Environment Network and Doug Weir of the Toxic Remnants of War Project. Coverage of the findings by the Washington Post.