Illicit drug production comes at an environmental cost; do the costs from Captagon production need investigating as part of a post-conflict environmental assessment for Syria?

The Assad regime’s embrace of Captagon production as a source of sanctions-busting revenue saw Syria become the world’s leading exporter of the drug. In this post, Leon Moreland examines whether we ought to be concerned about the industry’s largely undocumented environmental legacy.

The rise of the Syrian narco-state

Captagon is the street name for fenethylline, a synthetic stimulant created by chemically bonding amphetamine, a powerful central nervous system stimulant, with theophylline, a drug similar to caffeine commonly used to treat respiratory conditions. Developed in Germany in the 1960s, fenethylline was prescribed for conditions such as ADHD and narcolepsy. However, due to misuse and addiction, manufacturing was banned in 1986. Following the ban, production went underground with illicit fenethylline booming in south eastern Europe and parts of Asia.

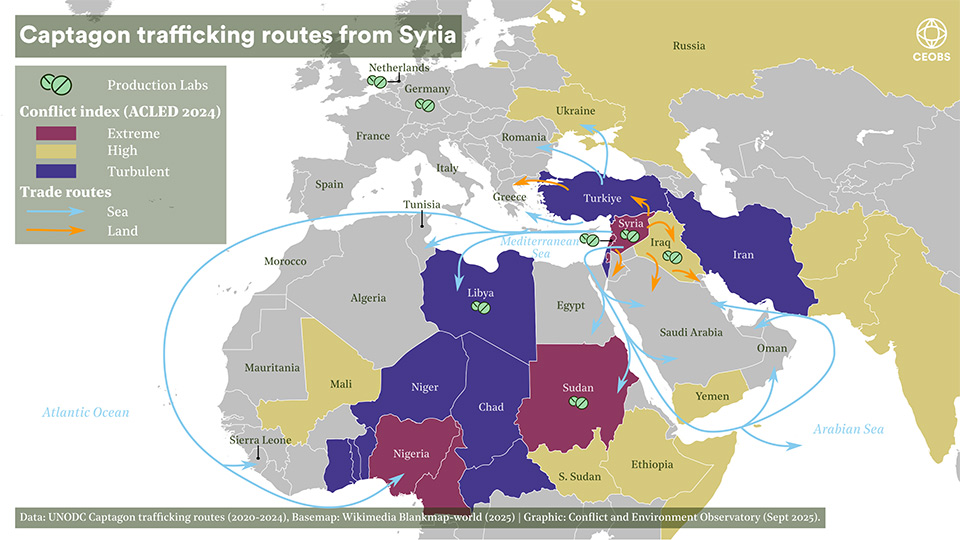

Under Bashar al-Assad, Syria became the world’s primary producer of Captagon, responsible for 80% of global production and distributed through an extensive trafficking network. To give a sense of scale, in 2020 Italian police intercepted a shipment weighing 14 tonnes and containing 84 million pills. After the collapse of Assad’s regime, the new Syrian authorities would discover a shipment of 100 million pills in the port of Latakia.

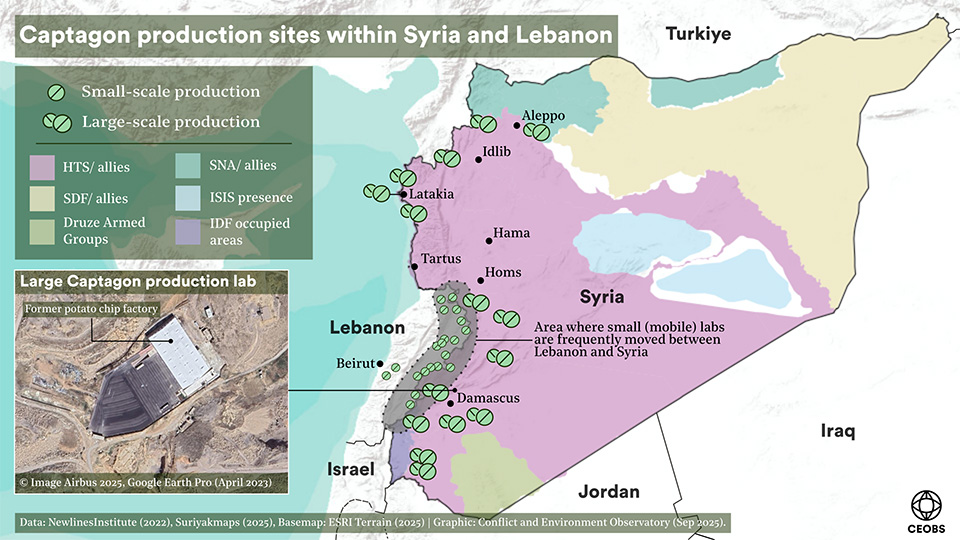

Sustained demand turned Captagon into the backbone of Syria’s wartime economy, supporting multiple parties involved in the country’s protracted civil conflict. Increasingly state-backed, by 2023 the illicit trade was estimated to be worth $5.7 billion, a critical income stream for a country under sanctions. The collapse of the Assad regime in December 2024 led to hopes that the flow of Captagon would ease. While the new interim government under President Ahmed Al-Sharaa announced the closure of state-backed production, non-state actors were less keen to forego the revenue and smaller, mobile labs have since emerged. Switching off the production tap did little to dampen consumer demand, particularly in Gulf and neighbouring countries, and seizures within Syria and the region have continued.

Described as ‘a symbol of structural dysfunction, geopolitical opportunism, and criminal innovation’, research has typically focused on the drug’s human health and security impacts. Fewer studies have considered the environmental impact of large scale Captagon production, particularly in a conflict context.

Captagon production and the environment

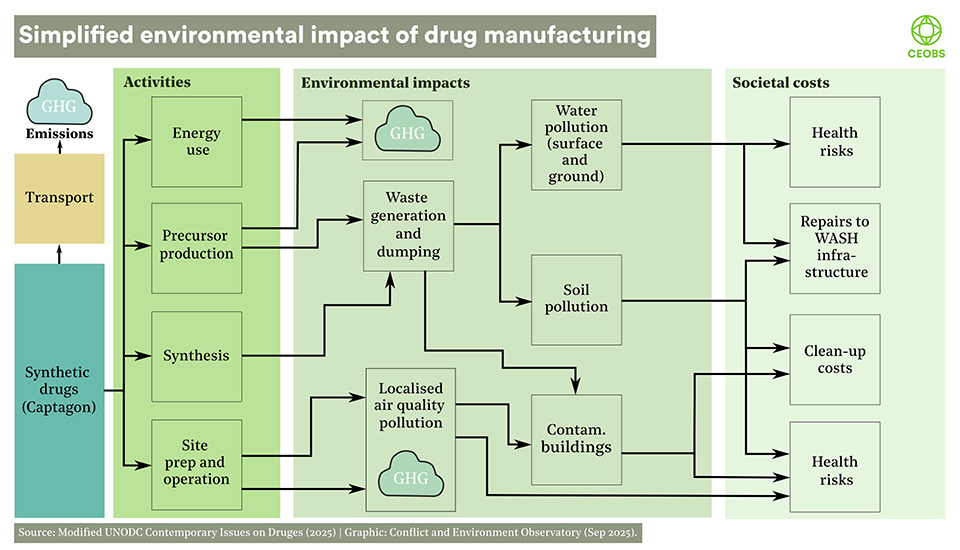

We could not find any studies specifically examining the pollution footprint from Syrian Captagon labs but data from EU amphetamine production and waste disposal sites, recently reviewed by the UN Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC), suggests that they could be significant.

Captagon production sites are associated with chemical pollution from waste streams, and potential pollution risks from stockpiles of precursor chemicals. Wastestreams vary by production process. In Syria, the most commonly reported process for the amphetamine component is the Leuckart Synthesis, which can be undertaken with basic expertise and is associated with formaldehyde and formic acid waste. The process typically produces around 40 kg of highly acidic toxic chemical waste per 1 kg of amphetamine.

The availability of precursor chemicals has varied over time, as has the efficiency and scale of laboratories. This has been reflected in the range of adulterants identified in Syrian Captagon pills tested in neighbouring countries,1 and presumably in the waste streams associated with production. Common precursor chemicals include phenyl 2-propanone, ammonium formate and the solvent formamide, the latter of which can be rapidly absorbed through the skin and respiratory tract, exposure is linked to long-term health risks including cancer, organ damage and reproductive effects. The rudimentary production methods, informal manufacturing settings, and range of potential chemicals involved mean that the health and environmental risks from different sites will vary widely.

Studies on the environmental impact of synthetic drugs are limited. Amphetamine has been shown to have acute impacts by disrupting freshwater ecosystems, while theophylline has been identified as an emerging contaminant of concern with the potential to bio-accumulate. It is toxic to humans in high doses and problematic for some animals. But it is the production wastes that are the main environmental concern, rather than Captagon itself. For example, had the 14 tonnes of Captagon seized in 2020 been pure amphetamine, its production would have generated between 420 and 560 tonnes of acidic waste; a total that does not include the additional wastes generated from combining amphetamine with theophylline into Captagon.

The scale of Captagon sites has changed over time, from small scale laboratories, to state-backed facilities and now appearing to trend to small mobile labs. Often sites would have been part of military bases, industrial areas or just hidden in residential properties. It is likely that there are hundreds of current and former Captagon production sites in Syria. One report identified 15 large-scale centres across former regime controlled areas, with many more smaller labs on smuggling routes along the border with Lebanon. However, comprehensive county-level data is unavailable.

Following the collapse of the Assad regime, journalists were able to access some previously secret sites. They reported large volumes of precursor chemicals, poorly stored or in leaking containers. We geolocated one such production site north of the city of Douma. A former potato chip factory that was constructed in 2021, it had been seized by Assad’s brother. Geolocation of this facility was straightforward thanks to its size and media attention but this is an exception, rather than the norm, indicating the challenge posed for efforts to identify potentially contaminated sites.

Given the clandestine nature of many facilities, and the conflict context, it seems highly unlikely that waste treatment or disposal was undertaken in an environmentally sound manner; something that may be exacerbated when production shifts to smaller, mobile settings, as is currently occurring in Syria. Instead wastes are likely to have been dumped nearby, poured into nearby drainage channels, or simply left in containers at production sites. In each case, the chemical wastes will pose an ongoing risk to the environment. Fly dumped liquid wastes from amphetamine production have been found to disrupt the functioning of wastewater treatment plants, thus potentially presenting an additional risk for Syria’s beleaguered water facilities.

A war on drugs?

Syria’s transition into a narco state proved politically problematic for its relations with neighbouring countries and with Gulf states. Keen to renew and stabilise its international relations, the new Syrian administration has sought to present a clear policy of Captagon eradication. This has included the very public disposal of seizures, shared on social media. Common methods of disposal include dumping into waste water systems, disposing at mixed landfills, and open air burning, all of which can be environmentally problematic.

The UNODC warns against using open air burning unless absolutely necessary; when it is used, it should be done away from people and have measures in place to prevent soil or groundwater pollution. We geolocated the image in the figure above to near the town of Al-Kiswah, south of Damascus. The site seems part of an informal landfill or brownfield site; low temperature incineration like this will leave combustion products and residues in soils.

Not just a Syrian problem

More than a decade of conflict has ravaged Syria’s environment, governance and infrastructure, and it faces health and ecological risks from a wide range of conflict pollutants, of which Captagon waste is just one. Syria needs international support to assess and understand the environmental consequences of the war and to identify opportunities for its sustainable recovery. Assessing and mapping major Captagon production sites should be part of that process.

While research into the environmental impact of the production of synthetic drugs is growing, it remains understudied. Activities such as waste dumping are inevitably a part of illicit production but may be more environmentally problematic in conflict-affected and insecure contexts where environmental governance is weak and where pollution incidents are less likely to be identified and addressed.

This is not just a Syrian problem. While Captagon production has slowed in Syria, global demand remains high. And true to its production being a symbol of “structural dysfunction”, Sudan has recently emerged as a new Captagon production hub, where the ongoing conflict and fractured governance has created the ideal conditions for manufacturing.

Leon Moreland is a Researcher with CEOBS, Dr Eoghan Darbyshire and Doug Weir contributed to this post. If you find our outputs useful, please consider donating to help support CEOBS’ continued work.