Proceedings of the first Military Emissions Gap Conference

Published: November, 2023 · Categories: Publications, Military emissions

The first international Military Emissions Gap conference Military and Conflict GHG Emissions: From Understanding to Mitigation took place in September 2023. In this review, members of the conference’s organising working group explore each panel in depth and the questions raised by audience members online and in person.

Contents

Panel 1: An overview of the military carbon footprint

Written by Dr Benjamin Neimark, Queen Mary University of London.

In this introductory session, a panel of experts outlined the varied sources of military emissions throughout the entire lifecycle. The panel hosted a mix of academics in conversation with civil society organisations providing an overview of the military carbon footprint and the challenges of navigating the sometimes messy and cumbersome problems of accessing reliable data. The panel displayed engaging scholarship including rich empirical research concerning the complex job of accounting for military emissions and associated environmental damage due to global conflict.

Linsey Cottrell, Environmental Policy Officer at The Conflict and Environment Observatory, provided an introduction to global military emissions reporting to the UN Framework Convention of Climate Change (UNFCCC) and presented a template framework developed by CEOBS to measure the full spectrum of military emissions. This includes scopes 1, 2, and 3, as outlined in the GHG Protocol, and presents an additional category, scope 3+, to capture emissions during conflicts.

Dr Carlos Ferreira, Senior Researcher for the Center for Industrial Ecology at the University of Coimbra, discussed the wider environmental effects of weapons manufacturing and engineering. He spoke of dealing with challenging restrictions in accessing the data necessary to fully assess the environmental impact of weapons across their life-cycle.

This was followed by Prof. Magnus Sparrevik, Adjunct professor in environmental sustainability at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. He described research conducted on life cycle assessments of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the Norwegian defence sector, which have allowed for a greater accuracy in carbon accounting.

The panel’s final speaker was Dr Reuben Larbi, from Lancaster University’s Concrete Impacts project. He spoke of the long-term carbon effects of concrete production as a weapon of war, focusing specifically on the carbon footprint from concrete walls used in the second Iraq war (2003-2008). This opening panel provided a point of departure around the importance of robust methodology and made calls for further independent research into military emissions.

The audience were keen to question the differences between panellists’ research methodologies and outcomes, such as how to avoid double counting and how research can move forward from dealing with limited emissions factors. Questions were also discussed on the difficulties of dealing with limited available data on military emissions, the frustrations this brings and the need to close the military emissions gap through thorough international reporting.

Panel 2: From bases to bombers: assessing the military’s organisational emissions

Written by Dr Stuart Parkinson, Scientists for Global Responsibility.

The second panel of the day focused on the military’s scope 1 and scope 2 GHG emissions. These scopes encompass the fuel use of all military vehicles on land, in the air, and on or in water, as well as the energy use of military bases, including direct heating and electricity use.

Prof. Neta Crawford, Montague Burton Chair in International Relations and Professorial Fellowship at Balliol College, University of Oxford, began the session with a review of data on US emissions, based on her estimates from 1970 to the present. She pointed out that emissions had largely risen and fallen with US military activity over the period, but that long-term declines mainly seem to be related to falls in the number of military bases and a shift away from coal use. She also argued that the government’s current military strategy – which continues to be focused on maintaining the world’s largest military by far, with especially high levels of spending and use of air power – ought to be questioned, as changes could help significantly reduce emissions.

Dr Stuart Parkinson, Executive Director of Scientists for Global Responsibility, focused on military emissions in the UK. He presented a series of graphs showing the available historical data for military bases and vehicles/craft. He pointed out some similarities to the US situation, such as emissions rising and falling with military activity, and long-term declines which mainly seem to be driven by falls in the levels of military personnel and decarbonisation of the UK’s national electricity grid. He also noted that long-term falls in the numbers of large fossil fuel-intensive craft, such as warships and combat planes, were similar in scale to reductions in emission levels from these craft since the 1990s. Echoing Prof Crawford, he highlighted the need to look beyond technological change, an option preferred by military voices, to reforming military and security strategies for further reductions.

James Clare, Director of Levelling Up, the Union, Climate Change and Sustainability at the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD), presented his assessment of the UK situation. He summarised the improvements in the MoD’s GHG emissions reporting over the past few years, including ‘re-baselining’ which resulted in a higher estimate of emissions from military bases. He pointed out that recent reductions in military base emissions are in line with central government targets for 2025, with stricter targets set for later years. He also pointed out that military aviation emissions have tended to be a large share of scope 1 and 2 emissions, and so he also discussed the MOD’s early work in testing alternative fuels, which are intended to be low carbon, and hence be a central element of the military’s emissions reduction efforts.

Prof. Oliver Heidrich, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Newcastle University, discussed his research project, the ViTAL Laboratory, which is a joint project with the RAF base at Leeming, North Yorkshire, UK. One aim of the project is to help improve the monitoring of energy use at an individual base. The project is also trialling measures to reduce GHG emissions at the base, including energy efficiency and renewable energy technologies, with a view towards rolling out successful options across the wider military estate.

Dr Axel Michaelowa, of Perspectives Climate Research, focused on the reporting of military and conflict-related GHG emissions under the UNFCCC. He pointed to gaps in the reporting of military emissions, not least those due to international military operations, which are exempt from national reporting. He also highlighted that conflict-related emissions – such as due to burning infrastructure and destruction of natural carbon sinks – can also be very large and not systematically reported. He argued for a concerted international effort to push for new guidelines for national reporting to ensure military and conflict-related emissions are consistently accounted for.

In the Q&A session, audience members took the opportunity to question the MoD’s ability to contribute to the UK’s net zero policy. For example, one audience member pointed out the MoD’s reliance on biofuel technology to achieve this target, as shipping and aviation are the main drivers of UK emissions, results in a high risk of the MoD not being able to deliver.

Other audience members looked to the wider role of the military within the climate crisis. One audience member pointed out that currently, the military is often at the frontline responding to natural disasters, events that will only increase at our current trajectory. Often, they explained, this is despite a lack of training and funding, which has led to death of personnel responding to wildfires. Another audience member did also raise that there are examples, such as in Austria, where civilian-led organisations can provide this frontline humanitarian response to the climate crisis.

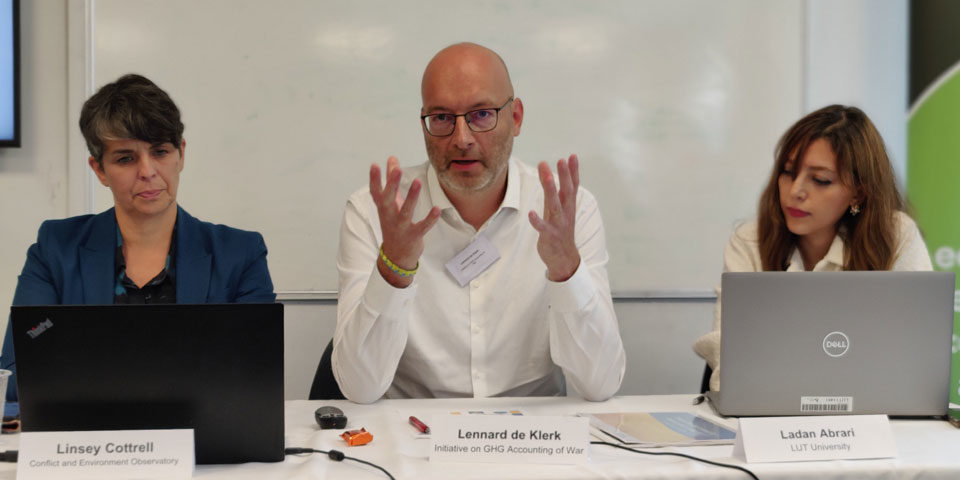

Panel 3: Understanding wartime emissions: lessons from Ukraine

Written by Lennard de Klerk, Initiative on GHG Accounting of War.

The conference’s third panel dealt specifically with conflict emissions, focusing on the war in Ukraine.

The first speaker, Lennard de Klerk of the Initiative on GHG Accounting of War, presented their report estimating the impact of the first 12 months of the war and the different sources of emissions within the conflict. He addressed some of the methodological issues dealing with conflict emissions, including the difficulties of setting the project boundaries and how estimating the counterfactual no-war scenario is challenging. There is no precedent in estimating conflict emissions in such a comprehensive way. He provided a first view of some ideas on how Russia might be held accountable for the climate damage it is causing, and how Ukraine can ‘undo’ these emissions through ensuring a low-carbon recovery.

The second speaker, Dr Mykola Shlapak, discussed the difficulties in getting solid data in the ‘fog of war’, in particular when it comes to the fossil fuel consumption for both militaries. He explained how many of the emissions do not happen on the frontline but rather in the logistical chain; for example the emissions caused by the manufacturing of ammunition are much larger than the emissions from its use.

The third speaker, Dr Sergiy Zibtsev, Head of the Regional Eastern Europe Fire Monitoring Center in Ukraine, gave an overview of how the armed conflict has damaged forest and other landscapes. He explained how this leads to significant GHG emissions, and the factors involved in estimating the total including identifying the species and age structure of forests, the total volume of biomass, and the amount of loss caused by the damage.

The fourth speaker, Prof. Rostyslav Bun, Professor at Lviv Polytechnic National University, focussed in particular on the reporting issues that result in conflict emissions not being included in national inventories. He presented estimations of emissions from different sources in the conflict, and questioned whether these should be accounted for by Ukraine, or Russia as the aggressor.

The last speaker Ladan Abrari, Junior Researcher at LUT University, presented her ongoing research into the environmental impact of the Second World War, and in particular how fuel consumption and consequent emissions evolved during the course of the war.

After the panellists presented, the audience had an opportunity to explore this newly evolving area of research. Both Lennard de Klerk and Rostyslav Bun have been estimating the overall climate impact of the war but both presented different estimates. The reasons for this were discussed, such as variations in methodologies such as the inclusion of different regions and territories, as well as the difficulty in accessing key data needed for an accurate estimate.

There was also a discussion on where responsibility should lie to measure emissions during conflicts – it may be understandable for a country to report the emissions that occur on its land, but this causes difficulties for occupied territories. The important point was raised that, in the ‘fog of war’, accuracy in accounting comes secondary to a fight for survival.

Panel 4: Military carbon footprints: how do we decarbonise?

Written by Linsey Cottrell, Conflict and Environment Observatory.

Panel 4 introduced the huge challenge of decarbonising the military, touching on the complexities and policies needed to drive meaningful change, and how or indeed whether militaries will decarbonise.

Dr Duncan Depledge from Loughborough University’s Net-Zero Military project set out the key issues. The high-carbon intensity needed to sustain current military capabilities is undisputed, and the military’s need to move away from fossil fuels is now difficult to ignore. Inherently, militaries will only do as much as possible, without compromising their operational effectiveness. There is a risk that few militaries will be engaged, since they do not see environmental protection as their role and during conflict, states are always prepared to suffer costs – be that lives lost, money spent or environmental damage. In times of war, militaries will not be making decisions based on their GHG emissions.

Military engagement on decarbonisation will likely be driven by the need to improve the security of energy supply, institutional reputation compared to the rest of society and recruitment, with climate-aware youth less willing to join carbon-intensive sectors, such as the military. Military decarbonisation is less about protecting the environment, and more about exploiting the advantages of a low-carbon energy transition and having a future tactical advantage. The Net-Zero Military project has identified four pathways that capture how decarbonisation may be achieved: refuel, repower, redirect and review.1 Under ‘review’, this covers the fundamental rethinking of military strategic posture and constraint, which is a big societal question and beyond decisions taken by the military alone. A combination of all four pathways will be needed. A key question will be, what are the indicators of success?

But as Finlay Asher from Safe Landing highlighted, is the ‘refuel’ pathway and consideration of alternate fuels such as synthetic or biofuels scalable and viable? On biofuels, the UK Royal Society has estimated that to meet existing UK civilian aviation demands alone, energy crops would require around half of all UK agricultural land. Synthetic aviation fuel (or e-fuels) is put forward as a viable solution by the sector, but it needs huge quantities of energy and is an inefficient use of renewable electricity in the wider move to decarbonise the economy. An offshore windfarm about the size of Northern Ireland would be needed to meet the renewable energy demands for the UK’s current civilian aviation fleet, if powered by e-fuels. Meanwhile, carbon offsetting has been widely debunked as a solution to the climate crisis.

Research by Dr Karen Bell included interviews with defence sector workers and union leaders in the UK and the US, which showed a diverse range of views on military decarbonisation and diversification. Some were strongly opposed, seeing it as irrelevant to the defence sector, risked a loss in capability and unrealistic. However, others recognised the need to limit arms production, with the opportunity to divert money to tackle global environmental issues and diversify into green sector jobs. However, defence sector jobs are seen as secure, and attract higher wages.

Clearly, it would be better to have no war at all or the need for the military, but it is not yet a reality. Does a cocktail of climate change, instability, pressure on and scarcity of natural resources also lead to increased security threats?

Vice Admiral Ben Bekkering, Rtd, member of the International Military Council on Climate and Security, discussed the military’s potential role in providing climate disaster relief, in helping to inform public debate on climate change and in demanding low-carbon solutions from its suppliers. In the Netherlands, the military is investigating existing low-carbon technologies and fuel efficiency, putting in place reporting and accounting systems, as well as carbon sequestration opportunities across its estate. However, the challenge cannot be addressed by the military alone, with researchers and engineers no longer in-house. This means turning to industrial partners and academics, but there are limits to technology solutions and whether they will be available in time.

Current military dialogue on ‘decarbonising’ assumes no reduction in capacity or demand. Yet, as raised during the panel discussion, the military must be incorporated as part of international climate negotiations. Keeping militaries just as strong by 2050 seems illogical. Resolving our international differences, eliminating the causes of war and strengthening diplomacy to address the climate emergency are critical. If humanity manages to decarbonise and reach the net zero goals of 2050, it will perhaps be the greatest collaborative achievement in international relations. And perhaps even a sign that military postures might be eased.

You can also read more reviews of the conference here:

Safe Landing at the Military Emissions Gap Conference

Columban Missionaries Britain – Military and conflict Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Independent Catholic News – Conference on impact of war on environment

- Refuel – maintaining similar assets but switching to alternative non-fossil fuels. Repower – alternative power systems, such as electrification or small nuclear modules. Redirect – outsourcing emissions to others (e.g. contractors or proxy forces), carbon sequestration or offsetting. Review – looking beyond technology fixes and focus on behavioural changes on how, when or whether militaries should be deployed.