The conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas region has had an impact on its environment, we take a first look at some of the problems the conflict has caused.

One year after violent conflict began, information is now emerging on the specific environmental impact of war in Ukraine’s highly industrialised Donbas region. Although obtaining accurate data is difficult, indications are that the conflict has resulted in a number of civilian health risks, and potentially long-term damage to its environment. In order to mitigate these long-term risks, international and domestic agencies will have to find ways to coordinate their efforts on documenting, assessing and addressing the damage.

Mapping the environmental impact of the conflict

The environmental legacy of conflict and military activities is rarely prioritised in post-conflict response, in spite of the short and long-term impact of damage on civilian health and livelihoods. At times relationships between incidents and harm may be complex, often requiring detailed and lengthy analysis. Warfare in highly industrialised areas has the potential to generate new pollution incidents and exacerbate existing problems; the conflict in Ukraine has done both, as well as damaging the area’s natural environment.

The chronology of the Donbas conflict is widely accessible and there is no need to repeat it here. More important is the current uncertainty. With the signing of the second round of Minsk agreements in February 2015, hope re-emerged that a peaceful solution might be possible. For the moment the truce is holding but remains fragile. Should it collapse, it is likely that new and grave risks to the region’s people and environment will emerge.

A map produced by Geneva’s Zoi environment network and the Kiev-based East Ukraine Environment Institute based on official information, media reports, assessments and interviews.

Scope of environmentally damaging incidents

Prior to the outbreak of the war, more than 5,300 industrial enterprises were operating in the pre-war Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts (provinces). Damage to the region’s industry is widespread, and ranges from direct damage to industrial installations, to enterprises simply stopping production because of the lack of raw materials, energy, workforce or distribution channels.

It is this disruption of the region’s industry that is likely to be primarily responsible for the environmental side-effects of the conflict. In some cases, the disruption has led to accidental releases of pollutants from shelled or bombed facilities. In others, facilities have been forced to shift to more polluting technologies that have impacted regional air quality. Among dozens of facilities damaged by fighting are the Zasyadko coal mine, a chemicals depot at Yasynivskyi coke and chemical works in Makiyvka, the Lysychyansk oil refinery, an explosives factory at Petrovske and a fuel-oil storage facility at Slavyansk thermal power plant.

Coal mining has been the backbone of the economy of the Donbas region since the nineteenth century. With the intermittent collapse of the electricity supply across the entire conflict area, ventilation systems and water pumps in coal mines failed, resulting in the release of accumulated gases after ventilation restarted. The often irreparable flooding of mines not only damages installations but also waterlogs adjacent areas and pollutes groundwater. At the time of writing, permanent or temporary flooding has been reported at more than ten mines, yet due to the lack of uninterrupted monitoring and fieldwork to assess the damage, the exact extent of the risks to environmental and public health is unclear.

The Zasyadko mine in Donetsk used to produce 4 million tonnes of coal annually and was one of the region’s economic flagships. A release and explosion of methane in March 2015 killed 33 of the 200 miners underground at the time. Even though this was not the first such accident at the mine (it is considered among the most lethal in the area’s risky mining industry), the chair of the mine’s board attributed the incident to heavy shelling at nearby Donetsk airport, where fighting continued until late January 2015.

There have been numerous media reports about war damage caused to Donbas’ water supply, including in and around Luhansk and Donetsk – cities that had a combined pre-war population of 1.5 million. Repair work to the water infrastructure is still carried out, often under direct fire, but periods of irregular supply are common. Less well documented is the impact of the conflict on drinking water quality but one can reasonably assume widespread deterioration as a result of the disruption.

At the moment, relatively little is known about the direct chemical impact of the war on the environment and people. Limited sampling by the Ukraine-based NGO Environment-People-Law confirmed the expected range of some ‘war chemicals’ from the use of conventional weapons in impact zones. Similarly, large quantities of damaged military equipment and potentially hazardous building rubble will require disposal. The Ukrainian Ministry of Defence also raised concerns that depleted uranium weapons may have been used in the fighting around Donetsk airport, and proposed to determine whether this was the case when conditions allowed.

The region’s nature has also suffered. Already prone to fires because of the dry summer climate, steppes and forests have burnt more often than would have been expected. According to an as yet unpublished analysis of NASA satellite data, the Eastern European branch of the Global Fire Monitoring Centre showed that in 2014, the incidence per unit area of forest and grass fires in the Donetsk oblast was up to two to three times higher than in the surrounding regions of Ukraine and Russia.

The conflict has also damaged the region’s numerous nature protection areas, from armed groups occupying their administrative buildings to the impact of fighting and the movement of heavy vehicles within nature reserves. The restoration of large tracts of agricultural and other land for normal cultivation and use will require considerable effort too, and will be complicated by the presence of new minefields and unexploded ordnance.

Challenges in determining the extent of damage

The prevailing media narrative over environmental damage from the conflict has sought to link it directly to the fighting, but the information currently available is too fragmented to fully confirm the extent of the relationship. Such simplifications can also mask the indirect effects of warfare on environmental quality.

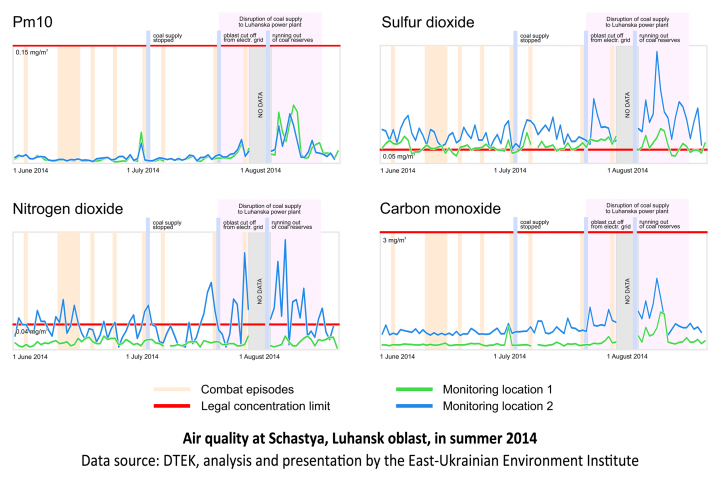

As is common for armed conflicts in heavily developed areas, a large proportion of the pollution impact may not come directly from the fighting but from damage to industrial infrastructure and to the disruption of everyday economic activities. A good example from the Donbas region can be seen in data from its only functioning (until November 2014) automated air quality monitoring station. Located in the town of Schastya in the Luhansk oblast, the data demonstrate that peak concentrations are not obviously associated with periods of combat; instead, they correlate with a reduction in the supply of high-grade coal for the Luhanska power plant in August 2014.

Coal supplies were first restricted when a bridge in Kondrashevskaya-Novaya was destroyed. Then an electrical substation was shelled, which disconnected the area from the rest of Ukraine’s electricity grid. As a result, the Luhanska power plant, which was responsible for supplying more than 90% of the oblasts’ electricity, was forced to simultaneously increase production while turning to lower-grade coal from its reserve stock. This caused a clear deterioration in air quality.

Coverage of the conflict has also claimed that the fighting has caused 20 times more wildfires than in 2013. While 2014 had seen more fires in comparison to the previous year, 2013 was relatively wet so this comparison is hardly informative. Assessing the exact area affected by fires in the territories remains difficult and imprecise, requiring the use of more refined data and techniques. The task is further complicated by the fact that forest fire statistics, which would normally be used to verify the findings from satellite data, are not being collected at the moment as the conflict has rendered large areas unsafe for ground surveys.

What next?

In spite of the fragile Minsk agreement, the half-frozen conflict continues. At present it is impossible to predict whether further damage will be wrought on the people and the environment of Donbas. Insecurity continues to impact basic environmental governance on both sides of the line of contact, while cooperation across the frontline, even on urgent humanitarian issues, remains a remote prospect. Therefore expectations for cooperation over environmental issues at the current stage in the conflict are low.

Based on the available evidence, it is clear that there is great potential for long-term civilian health risks from the pollution generated by the conflict. Efforts to collect systematic data on both pollution and health outcomes should start immediately, as must preparations for remediation. The financial and technical requirements for the comprehensive assessment and remediation of contaminated sites are considerable.

These are problems common to many conflicts affected by toxic remnants of war and, as the ICRC noted in 2011, consideration should be given to whether a new system that ensures environmental assistance is required in order to protect both civilians and the environment from conflict pollution:

“…given the complexity, for example, of repairing damaged plants and installations or cleaning up polluted soil and rubble, it would also be desirable to develop norms on international assistance and cooperation. …. Such norms would open new and promising avenues for handling the environmental consequences of war.”

The broader context for the eventual remediation of the environmental damage should include the radical modernisation of the region’s notoriously unsustainable industry, much of which has for years presented direct and grave risks for its environment and people (see Zoi’s 2011 report Coalland). In this way, quite unexpectedly, the highly unwelcome conflict may in the end offer a rare and welcome opportunity to eventually ‘green’ the black and brown coalfields of Donbas.

This blog was originally prepared for sustainablesecurity.org by Nickolai Denisov and Otto Simonett of Zoi environment networktogether with Doug Weir of the Toxic Remnants of War Project in Manchester and Dmytro Averin of the East-Ukrainian Environment Institute in Kyiv – Slovyansk. We thank Serhiy Zibtsev, Victor Mironyuk and Vadym Bohomolov, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine / Regional Eastern European Fire Monitoring Center, for help with the analysis of forest and grassland fires data.

Zoi environment network is a non-profit organisation in Geneva, Switzerland, with the mission to reveal, explain and communicate connections between the environment and society and a long record of working on environmental issues in and with the countries of Eastern Europe.

Additional reading about (pre-war) environmental issues in Donbas

Coalland. Faces of Donetsk. Zoï environment network and UNEP / GRID-Arendal, Environment and Security initiative. Geneva, 2011

The Land of our Concern – based on material from the Reports on the State of the Natural Environment in Donetsk Oblast, 2010. State Environmental Protection Administration in the Donetsk oblast. Donetsk. 2011