5. The coastal and marine environment

Published: February, 2023 · Categories: Publications, Ukraine

Читайте українською

This is the fifth in a series of thematic briefings on the environmental consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, jointly prepared by the Conflict and Environment Observatory and Zoï Environment Network. This work is supported by the United Nations Environment Programme as part of its efforts to monitor the environmental situation in Ukraine.

Situation

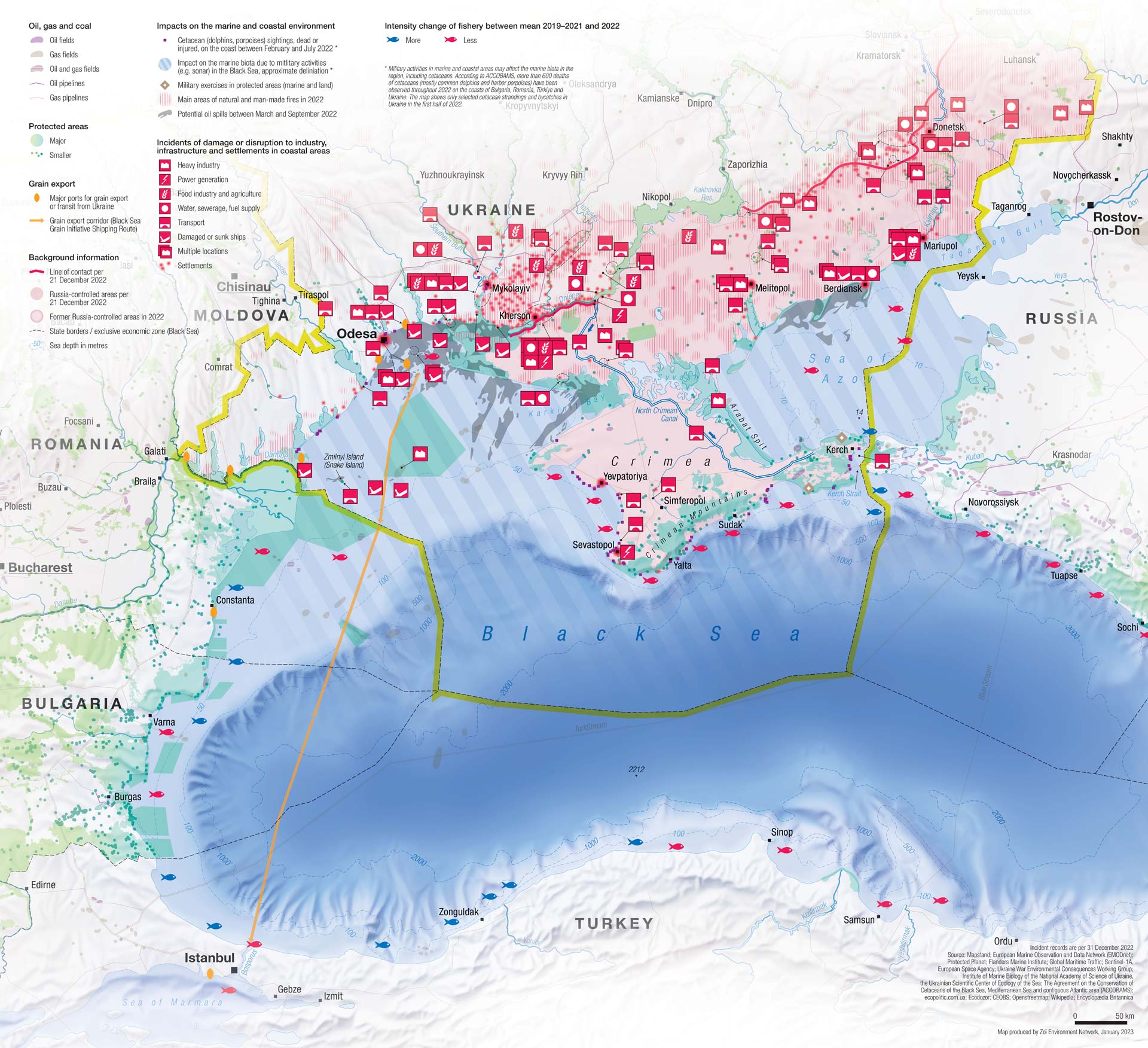

A wide range of land and marine-based military activities are placing Ukraine’s marine ecosystems at risk, while fragile and ecologically sensitive coastal habitats have been directly affected by the fighting. Further research will be needed to determine the true impact of the conflict on the ecology of the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and estuaries and wetlands, but as these waters were already facing a range of human-induced pressures including pollution, overfishing, invasive alien species and climate change, these impacts could be significant.

Contents

Overview and key themes

Ukraine has around 2,700 km of coastline along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Russia’s 2014 annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, and the occupation of Donetsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson oblasts as a result of the armed conflict since February 2022, have meant that Ukraine has lost access to much of its southern and south-eastern coastline.

Both the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov have suffered decades of environmental degradation, which has been compounded by their geography. The Black Sea receives the discharges of Europe’s three largest rivers, and its catchment area is around five times greater than its surface area. Because this includes major industrial and agricultural regions, pollution problems have been common. The Black Sea’s great depth and shallow outlet result in little water mixing, and below 100 – 150 m it is largely devoid of oxygen. The Sea of Azov meanwhile is extremely shallow, and dominated by the inflow of the Don and Kuban rivers. The nutrients they brought to its shallow waters once supported high fish stocks, however eutrophication, pollution and overfishing have degraded the sea’s ecosystem.

Ukraine’s Black and Azov sea coasts face a range of environmental pressures linked to the ongoing armed conflict, this includes threats to ecologically important areas and valuable fisheries.

Ecologically important areas have been shrinking, with the small and valuable remaining areas continuing to be threatened. Ukraine’s important coastal and marine ecological areas include 22 Ramsar Sites covering 750,521 ha, numerous terrestrial Protected Areas (PAs), as well as 45 designated Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). Yet, Ukraine’s MPAs designate just 1.3% of its total marine area as protected, and the status of that protection is poor. This has contributed to high levels of illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in the Black and Azov seas, although poor product traceability, and weak fisheries governance remain more influential. As a result of the annexation of Crimea, Ukraine lost access to 11 MPAs within its coastal zone. Since February 2022, access to the marine components of two further PAs have been lost: the Сhornomorsky Biosphere Reserve, and the National Natural Park “Biloberezhia Sviatoslava”, both of which are in southern Kherson.

Plans to expand marine and coastal PAs have been underway since 2016, but have been hampered by the annexation of Crimea, as well as by ongoing military activities. Plans have included an expansion of the Karkinitsky Bay PA, and new MPAs along the Crimean coast and in the west of the Sea of Azov, which were planned to be delivered by 2023. These plans would have resulted in 19 new MPAs along the Crimean coast of the Black Sea, with a significant increase of much needed protection for the ecologically significant Kerch Straits. Ukrainian conservationists have also proposed that the entirety of the western section of the Azov Sea – some 14,251 km2 – be designated as one continuous MPA.

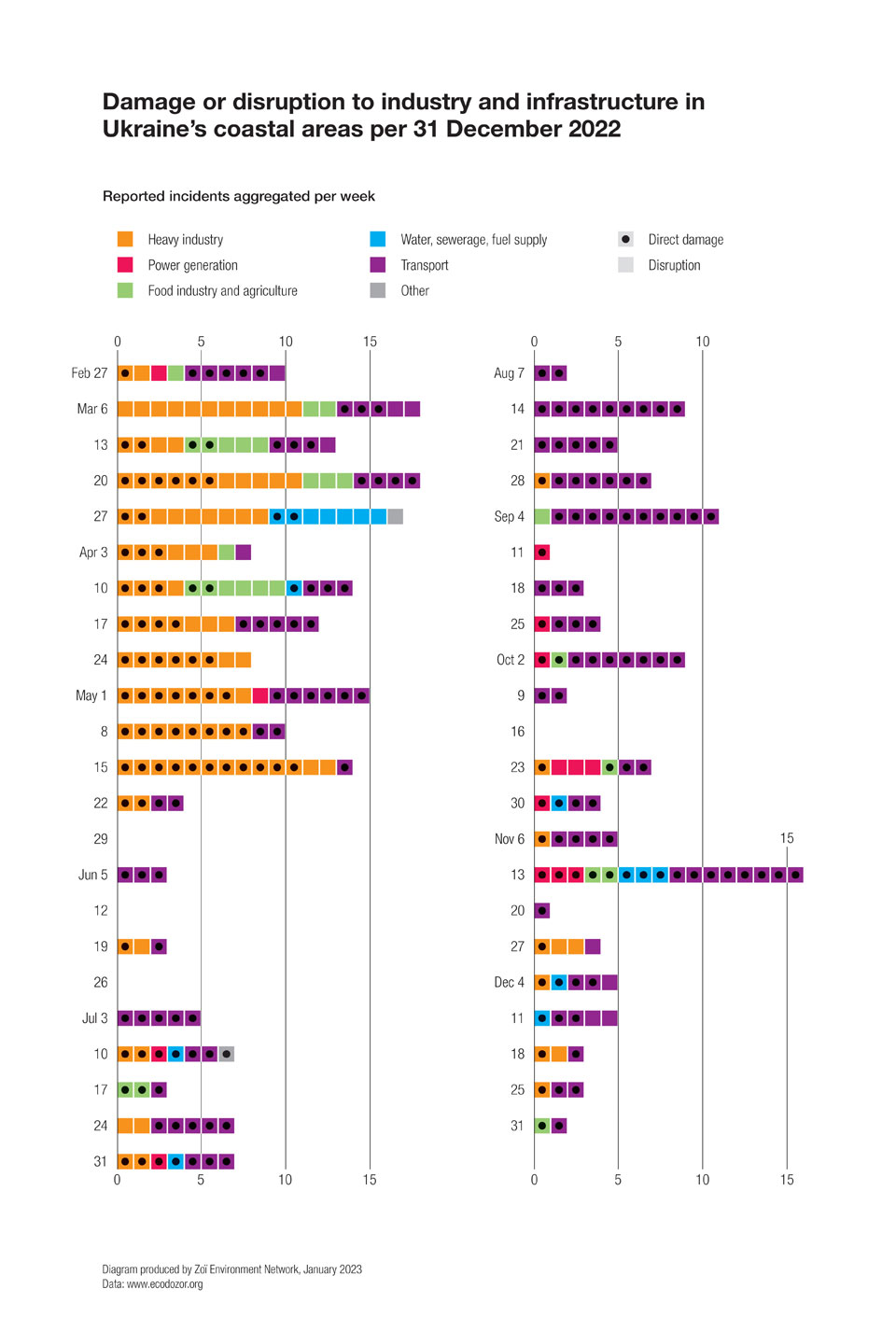

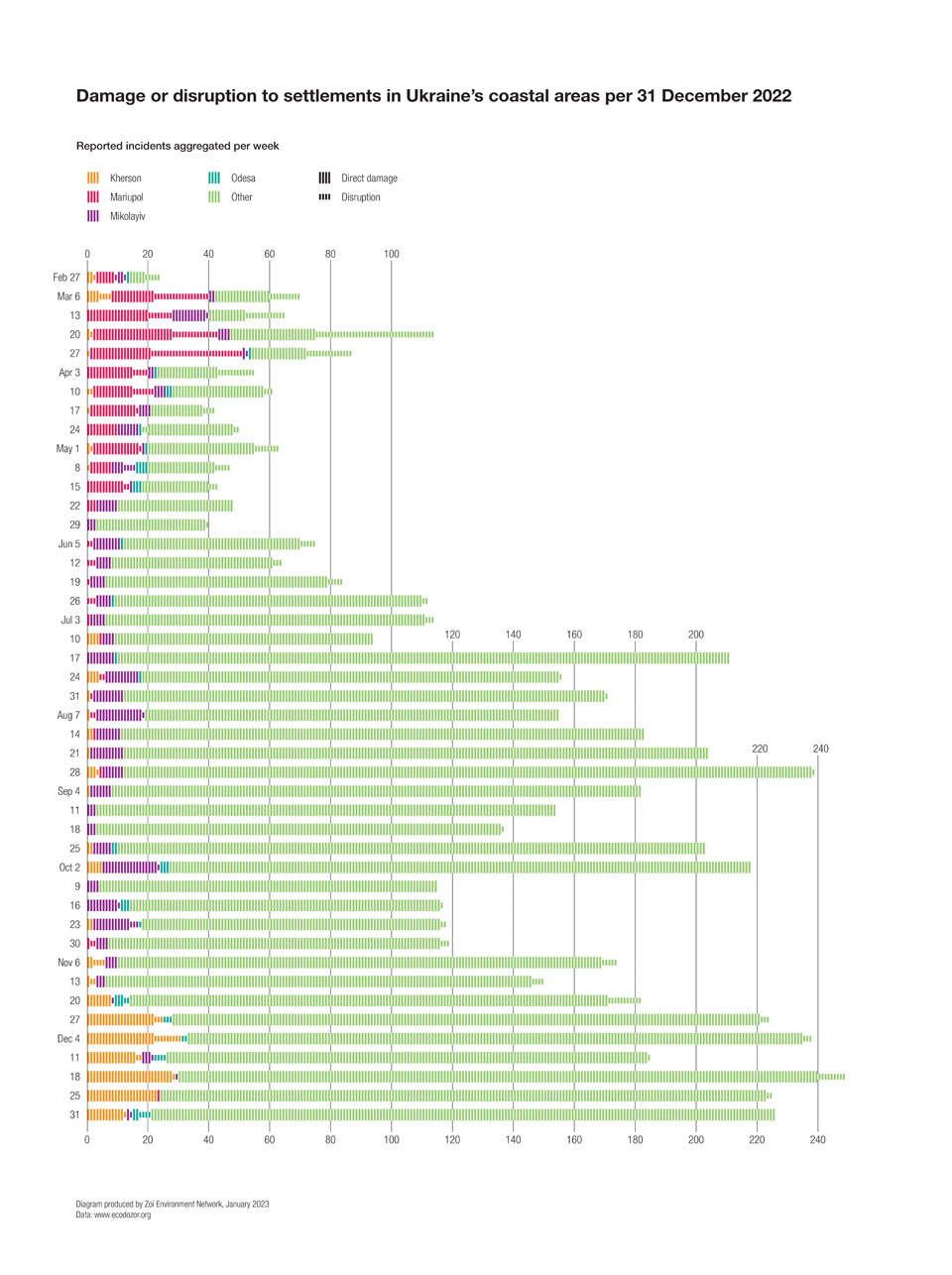

The primary impacts of the armed conflict on coastal and marine ecosystems include chemical and acoustic pollution, physical damage to habitats and the curtailment of conservation activities. The conflict has also impeded environmental monitoring and governance of the Black and Azov seas. Damaged industry and settlements can be important sources of chemical pollution in the coastal and marine environment. Ecodozor data reveal an increase in reported damage and disruption to coastal settlements as the conflict has progressed, whereas there has been a decline in reported incidents affecting heavy industry in coastal locations over the same period.

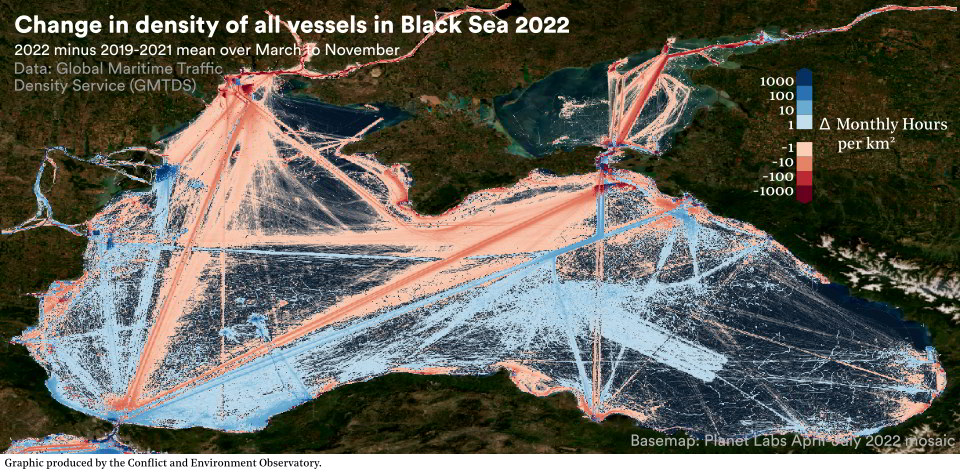

The tempo of naval activities is also an important determinant of environmental harm, and has changed markedly as the conflict has gone on. In its earliest phase, Russia’s Black Sea fleet targeted Ukrainian naval facilities and settlements. Attacks were carried out on both military and civilian shipping with Russian naval forces operating close to strategically important ports such as Odesa. By early April, Russia appeared to decide not to commit to landings between Mykolaiv and Odesa using two large amphibious detachments that it had formed. In late May 2022, Ukraine received Harpoon missiles, plugging a gap remaining in spite of Ukraine’s accelerated rollout of its own indigenous Neptune missiles; this dramatically changed the strategic picture, forcing Russian naval forces away from the coast. From September, Ukraine’s increasing use of marine drones and high profile attacks on naval facilities at Sevastopol (Crimea, Ukraine) and Novorossiysk (the Caucasus coast, Russia) has kept most of Russia’s fleet in port, although surface vessels and submarines have repeatedly been used to launch cruise missiles at Ukraine. Although international legal provisions protecting ecologically important areas from the effects of naval warfare were set out in the 1994 San Remo manual, these remain non-binding.

Chemical and acoustic pollution

Coastal and marine ecosystems are likely to have been impacted by chemical pollution from both terrestrial and marine sources. Damage and disruption to upstream water and sanitation infrastructure from both physical damage and de-energisation is expected to have increased wastewater discharges. The targeting of industrial and port facilities along rivers, estuaries and coasts has led to well-documented pollution incidents. At other sites, such as the coastal Azovstal steelworks in Mariupol, the ongoing occupation has made it impossible to determine the risk to the coastal environment. At the same time, pollution risks created by the conflict need to be considered in the context of reductions in discharges at some sites due to lower industrial activity and temporary outmigration. Ukraine’s Ministry of Environment has found only a slight increase in pollution from heavy metals in the Dnieper, compared to 2021, which was still within Ukraine’s water quality standards.

In the early phase of the conflict, attacks on naval facilities led to documented pollution incidents. This includes a Russian attack on the port of Ochakiv in February 2022, and Ukraine’s attacks on Russian vessels at the captured port of Berdyansk in March. Later, Ukraine’s aerial and marine drone attacks on port facilities at Sevastopol and Saky airbase in Crimea, and an oil terminal at Novorossiysk entailed varying risks to the environment.

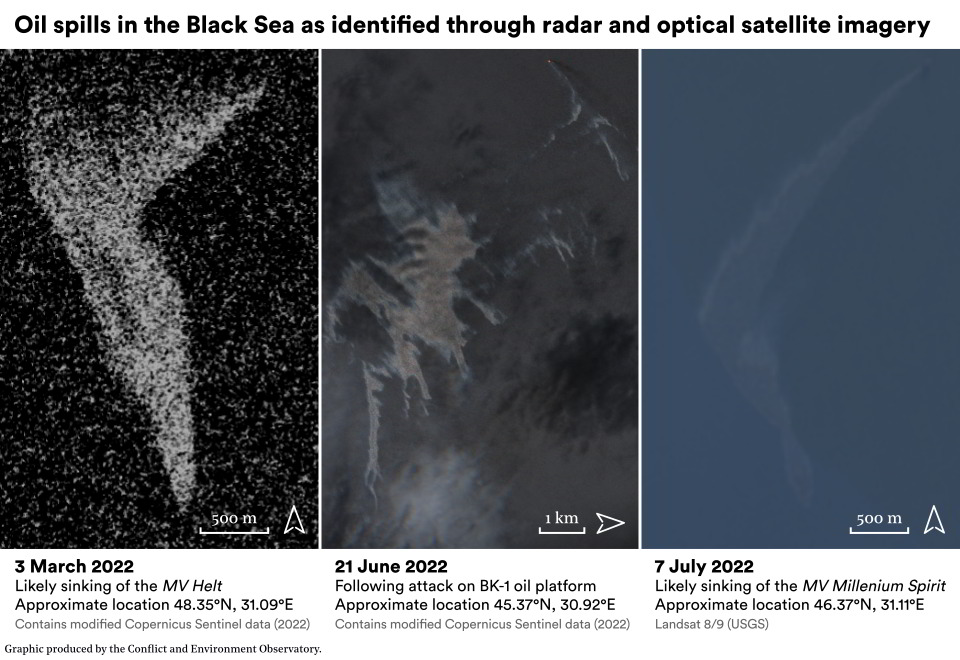

Civilian and military shipping has been targeted by both sides, and in concert with the tempo of naval activities, the majority of incidents occurred during the initial months of the conflict. Civilian ships have been targeted both at sea and in port. The cargo carriers the Helt and Azburg were sunk, while the chemical carrier Millennial Spirit was abandoned on fire and eventually sank off Odesa after drifting, and being struck for a second time. Spills from vessels are reported to have placed protected wetlands at risk, while the widespread use of naval mines increases the risk to vessels and subsequent risks of discharges to the environment should they strike them.

A number of small naval patrol, assault and landing boats have been sunk on both sides, with other larger vessels sunk or scuttled in port. However, the most notorious incident has been the sinking of the Moskva guided missile cruiser after it was struck by Ukrainian missiles. The Moskva is thought to have sunk in water 45-50 m deep and wrecks can become persistent sources of pollutants into the local environment. Small oil slicks were used to pinpoint the location of the wreck.

A significant oil spill followed Ukraine’s targeting of two Black Sea gas drilling rigs off Crimea that had been occupied by Russia and which were reportedly being used to monitor the Black Sea. The rigs were being operated by Chernomorneftegaz, a subsidiary of Ukraine’s state producer Naftogaz until its seizure by Crimea’s authorities after the annexation. The attacks triggered a fire at the BK-1 platform that has been burning since June 2022, together with a high likelihood of methane leaks.

There has been significant international media attention on the rates of dolphin and harbour porpoise strandings since February. The active sonar systems used by navies for detecting underwater vessels have long been associated with cetacean strandings, while data on the intensity of sonar use in the Black Sea is not available, it seems likely to have increased as a result of the conflict. The shallow waters of the Sea of Azov makes active sonar less valuable. While Ukrainian researchers are convinced that there has been a significant increase in strandings, and that military activities are to blame, definitive evidence is still absent. Researchers from the regional treaty body ACCOBAMS have suggested a more modest increase but based on a different methodology.1

Samples from six stranded animals – harbour porpoise (Phocene phocena) and common dolphin (Delphinus delphis) – have been collected and are expected to be analysed at the universities of Padua and Hannover. Pre-war, stranded animals were often marked with traces of poachers’ nets or with fins removed, the preliminary results from recently found carcasses showed animals sustained body injuries unrelated to those inflicted by fishing nets.

Habitat disruption

The conflict and occupation have resulted in or exacerbated damage and disruption to a range of coastal and marine habitats, many of which are fragile or highly sensitive. However, in most cases, it is difficult to determine the precise impact on the populations of particular species without field research. The examples below illustrate the range of threats that the conflict is generating for coastal and marine habitats.

The presence of unexploded ordnance and mines has been reported at numerous locations. Fires have been caused in coastal scrub and forests in PAs such as the Biloberezhia Sviatoslava NNP as a result of them being targeted or used as firing positions. Minefields have been laid on beaches and coasts to prevent amphibious landings, while both Russia and Ukraine have deployed sea mines.

The construction of trenches and fortifications damages flora and increases soil erosion, while the refuse and military waste left by personnel pollutes soils and groundwater. As frontlines move, so too does the line of physical damage to habitats, particularly where they are subjected to heavy shelling. One example of this are the ecologically sensitive wetlands along the Dnieper estuary in south Kherson that were fortified by Russia following its withdrawal from Kherson city. In Crimea, important coastal habitats are reported to have been turned into military training grounds. Alongside the physical disruption, noise disturbance has likely affected bird and mammal species.

Fighting has also impacted offshore habitats. Zmiinyi (Snake) Island became the site of intense fighting between February and July, with the use of both heavy explosive and incendiary weapons. Part of the island and surrounding waters were designated as an MPA in 1998, and it is inevitable that its terrestrial biodiversity has suffered serious harm, impacts on its marine ecosystem are harder to gauge..

Another MPA of concern is the unique Zernov’s Phyllophora Field. The largest MPA in the Black Sea, the area was established to protect the recovery of Phyllophora algae, a keystone genus and ecosystem engineer. Prior to the conflict this MPA was already at particular risk from excess sediment and nutrient loading and would be affected by increased discharges from Ukraine’s rivers. Within the MPA borders there have been multiple oil spills and ship sinkings, including the Moskva. However, reduced pressure from trawling could be beneficial.

Fisheries and shipping

The conflict has had a significant impact on marine traffic in the Black and Azov seas, and altered fisheries governance and control. Changes in fishing intensity and location can influence fish stocks, while reductions in shipping can have beneficial effects for the marine environment. Analysis by the FAO has found that Ukrainian sea fishery fleets were inactive throughout 2022, with almost the total annual Black and Azov sea catch of 13,000 tonnes lost. Inland and delta fisheries were also impacted.

Prior to the conflict, fishing and freedom of navigation in the Azov Sea and the Kerch Strait, through which it connects to the Black Sea, were governed by bilateral treaties between Ukraine and Russia. The sea was deemed an inland waterway of both countries and each was allowed to fish anywhere. Variations in salinity across the Azov had created a diverse fishery with a wide range of target species. Alongside the legitimate fishery, there was thought to be a significant but understudied illegal sturgeon fishery. Bilateral fishery agreements were developed by the Ukrainian-Russian Commission for Fisheries in the Sea of Azov, which was established in 1992 after the collapse of the USSR.

During 2022, Ukraine’s parliament moved to terminate many bilateral agreements with Russia, and is currently considering the treaty governing the use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait. Its termination and the conflict are only the latest shift in fisheries governance. Following its annexation of Crimea, Russia unilaterally reduced the section of the Azov Sea where Ukrainian fisherfolk were allowed to fish by 75%; around 100 Ukrainian small-boats had fished in the sea of Azov prior to this. This had a particularly significant impact on Ukrainian fisherfolk due to a high level of dependency on Crimea’s coastal waters. The termination of fishery agreements during 2022 means that there is currently no joint management in the Sea of Azov.

Our analysis of fishing vessel transponder (AIS) data has found that fishing by Russian trawlers intensified in the Black Sea following the annexation of Crimea in 2014. More recently, from March to June 2022, overall fishing activity decreased in the Black Sea, with fishing vessels staying close to the shore. Between June and December, fishing intensity returned largely to its pre-war pattern, perhaps reflecting the dynamics of naval activity. The situation in the Sea of Azov is similar; from February to May 2022, fishing decreased, returning to its pre-conflict pattern by August, but between September and November fishing by Russian vessels in the Sea of Azov was more intense than pre-conflict levels. It should be noted that AIS data does not tell the whole story, as vessels fishing illegally will turn off their transponders.

With the exception of fishing hotspots around the Kerch Strait and the Sea of Azov, our analysis of AIS data for the Black and Azov seas between March and November 2022 found a sharp decline in marine traffic, due in part to the Russian naval blockade. Shipping has a number of environmental impacts, contributing to air, water, oil and acoustic pollution and the spread of invasive alien species. In this regard it is likely that pressures on the marine environment from commercial shipping also declined significantly, particularly along the Crimean coastline.

Although the conflict is reported to have impacted mariculture in Ukraine, it has not prevented the development of legislation intended to create a more transparent mechanism for its expansion.

| Incident patterns in selected coastal and marine areas, Feb – Oct 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Area | Incidents |

| Coastal cities and ports. | Repeated attacks on Odesa, Ochakiv, Mykolaiv, Kherson, Skadovsk, Melitopol, Berdyansk, Mariupol and Sevastopol, resulting in sunken ships and damage to coastal infrastructure. |

| The Black and Azov sea coasts, the basins and deltas of the Dnieper, the Southern Buh, and the rivers of the Donbas. | High intensity warfare resulting in widespread damage to settlements, industries, critical infrastructure, land and the natural environment. |

| Open seas. | Repeated attacks on civilian and military ships, fighting on and around Zmiinyi (Snake) Island, missile attacks on gas drilling rigs, impact of military activities on cetacean populations. |

Case study: The Buh Estuary

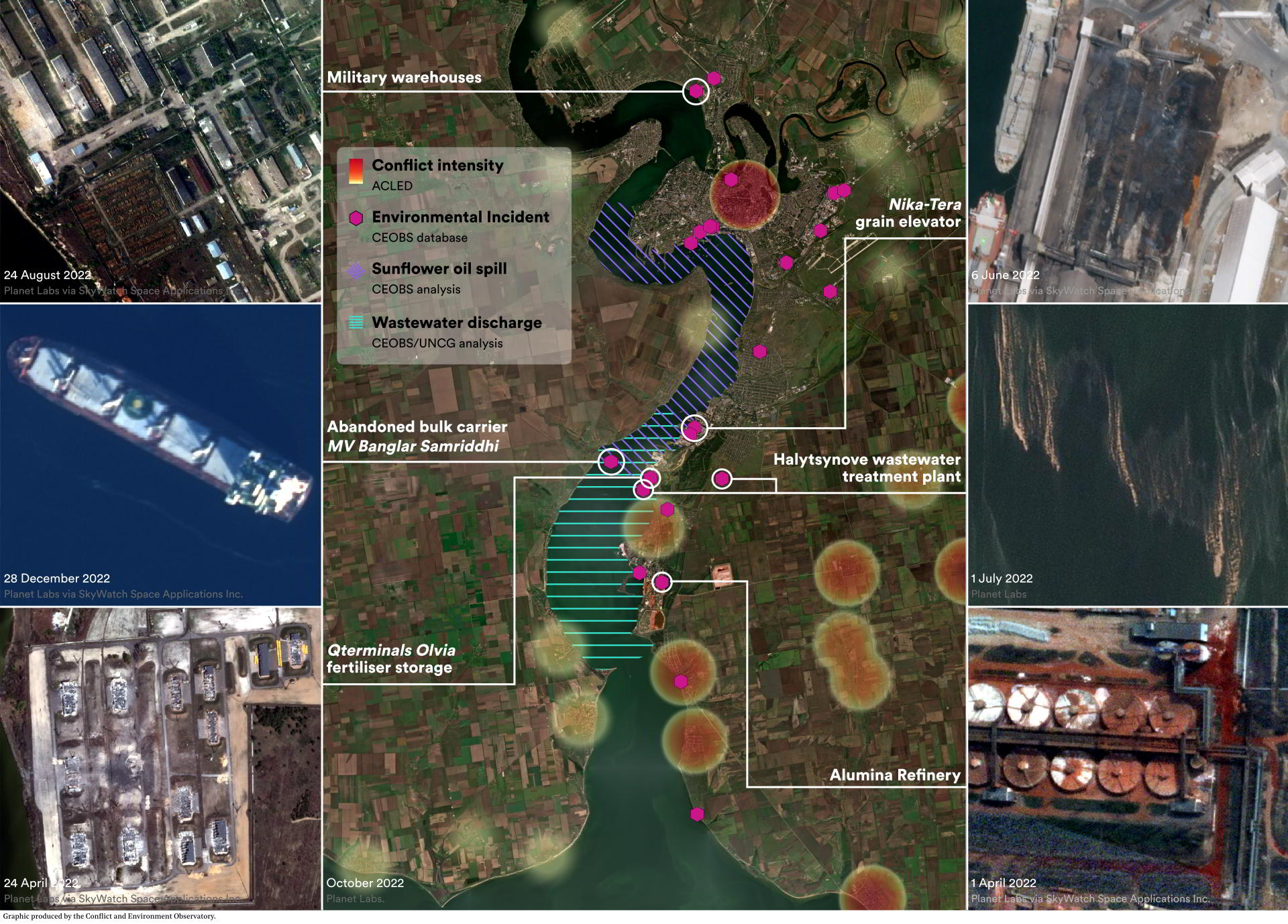

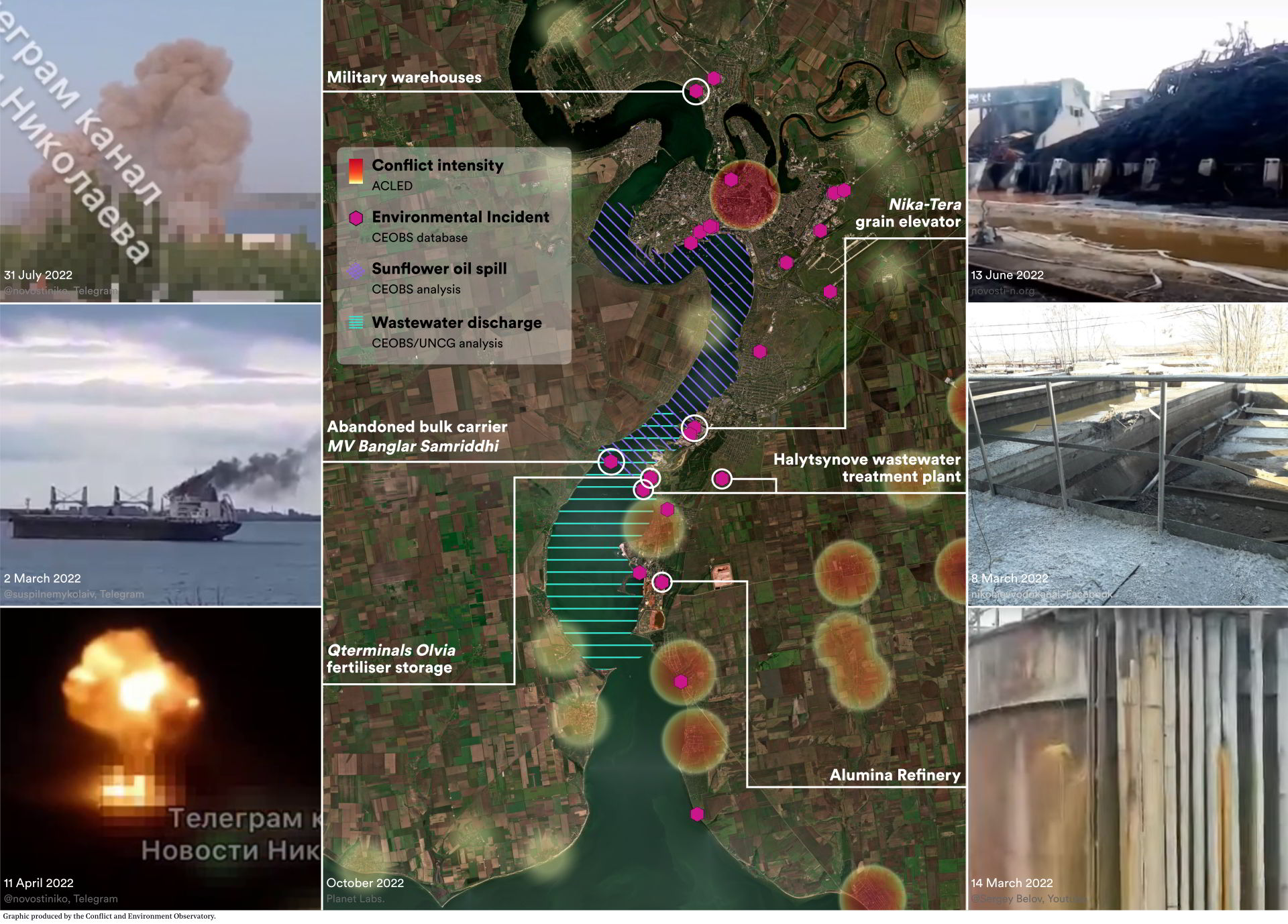

Estuaries are unique aquatic ecosystems, key locations for biogeochemical cycling, and we are becoming increasingly aware of the many ecosystem services they provide. These sensitive transitional zones are particularly vulnerable to changes and, since February 2022, Ukraine’s Buh estuary has seen changes aplenty.

The Buh estuary is in southern Ukraine and passes through the city of Mykolaiv before meeting with the Dneiper and forming the Dnieper-Buh estuary. These waters form part of the Dniprovsko-Buzkyi Lyman (Dnieper-Buh estuary) Protected Area, support a high diversity of species and in particular are an important corridor for migratory birds. The estuarine water quality is also important from an environmental health perspective – since May 2022 it has been pumped into homes for non-drinking use, owing to the local water crisis caused by attacks on water pumping infrastructure in April, and as recently as November.

Incidents leading to a pollution risk

There was a major offensive on Mykolaiv between February and May 2022, during which time Russian troops occupied much of the left bank of the estuary. Although no longer on the frontline, Mykolaiv has endured prolonged artillery and missile attacks, particularly until the liberation of Kherson in November. As a result, Mykolaiv and nearby towns have sustained significant physical damage, generating large volumes of conflict debris. This will be contaminated with a broad range of pollutants, including heavy metals, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and asbestos. Some of these hazardous materials have been or will be transported into the Buh estuary through surface run-off or via groundwater flow.

There have also been numerous incidents with particular environmental risks. The Buh estuary is a key shipping port and many of the industrial facilities that line the left bank have been damaged. For example, the Alumina Refinery was targeted in March and October,2 with satellite imagery confirming damage across the site, including to buildings and tanks storing fuel, caustic soda,3 and processed materials. Satellite imagery on 22nd April shows a large leak, likely of bauxite residue – this has a high alkalinity, contains heavy metals, and even trace radioactive elements.

Locations and types of pollution incidents documented and verified by CEOBS in the Buh Estuary, slider toggles between satellite imagery and footage from social media reporting. Social media sources: Military warehouses, MV Banglar Samriddhi, Qterminals Oliva, Nika-Tera, Halytsynove treatment plant, Alumina refinery.

Approximately 10 km upstream is the Nika-Tera grain terminal, which was attacked in June, leading to a huge fire that spread into nearby forestry. Satellite imagery shows damage to three warehouses, possibly storing ammonium nitrate fertiliser, and surrounding pools of brown water – likely contaminated with firefighting foams and fertiliser and therefore posing an environmental risk to the estuary. Thankfully firefighters were able to contain the fire and it did not spread to the adjacent docked ships – such as the MTM Rio Grande, an oil/chemical tanker that had earlier been targeted in May. The sinking of these vessels would likely release significant volumes of fuel and lubricants into the estuary. One ship of particular concern is the bulk carrier MV Banglar Samriddhi, which was attacked and ablaze in March, damaged again in June, and is now floating abandoned in the middle of the Buh estuary.

The MV Banglar Samriddhi was initially attacked when it was in port at the Olvia QTerminals agro-products seaport. This was attacked in March and, most significantly, in April. Satellite imagery shows huge damage to 13 out of 14 warehouses that are enclosed by berms – this suggests storage of ammonium nitrate fertiliser, or potentially munitions. Nearby, warehouses north of Mykolaiv may have contained large volumes of munitions. Indeed, contaminants from toxic munitions compounds and military materiel are likely to have entered the estuary and its upstream waters from numerous locations.

Away from the direct conflict impacts are a host of indirect changes. Some of these may have positive ecological consequences, such as the suspension of industrial activities and shipping – the estuary waters and sediments suffer from a legacy of pollution. There are also unknowns, such as changes to dredging practices, or to agricultural runoff, which may have altered as croplands turned into battlefields.

One more visible indirect impact was the discharge of sewage between 28 June and 15 July from the Halytsynove wastewater treatment plant. This was likely associated with widespread damage to Mykolaiv’s water supply and network, and an attack on the facility in March. Such releases of untreated wastewater can harm ecosystems through the release of toxic substances and eutrophication.

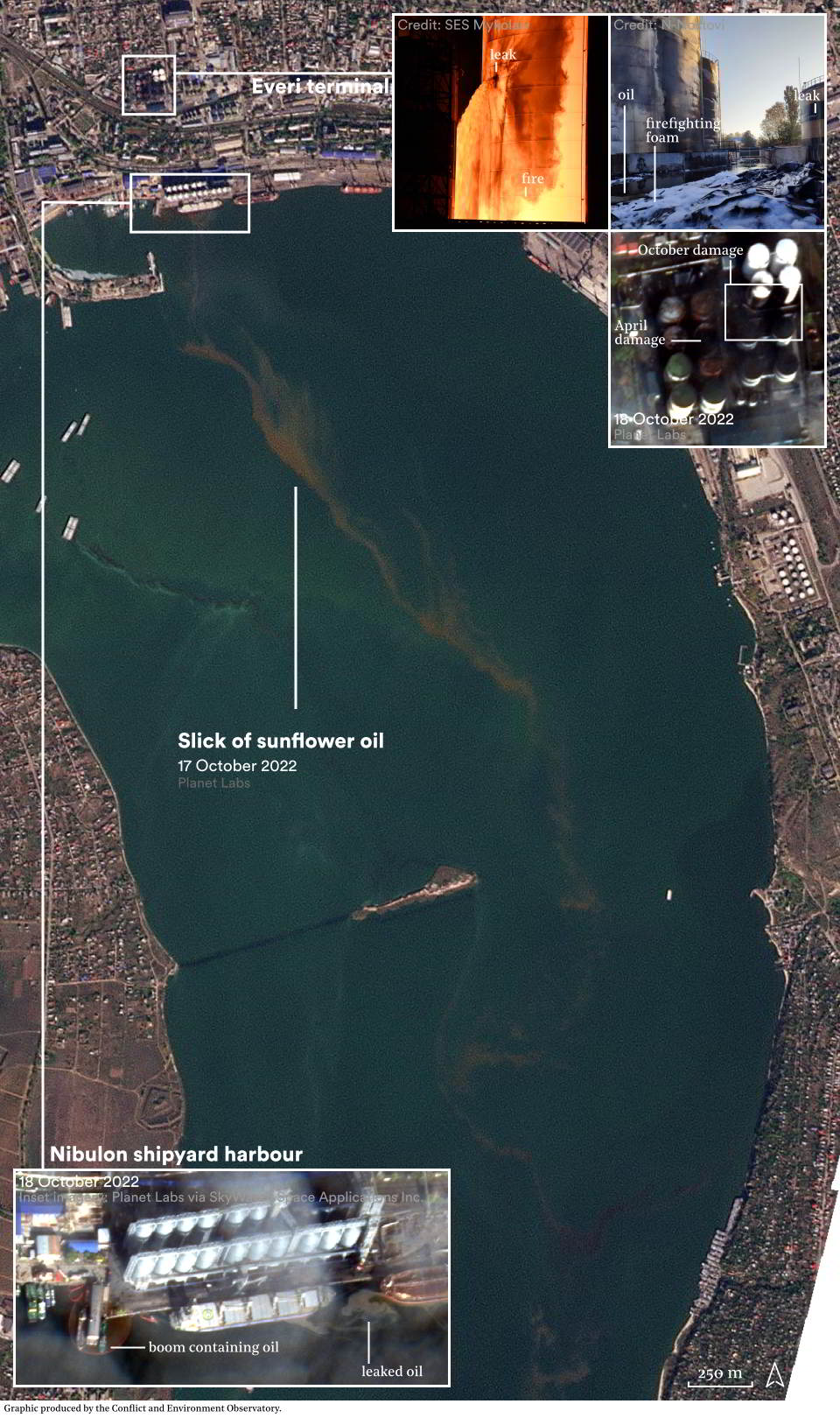

Everi terminal sunflower oil spill

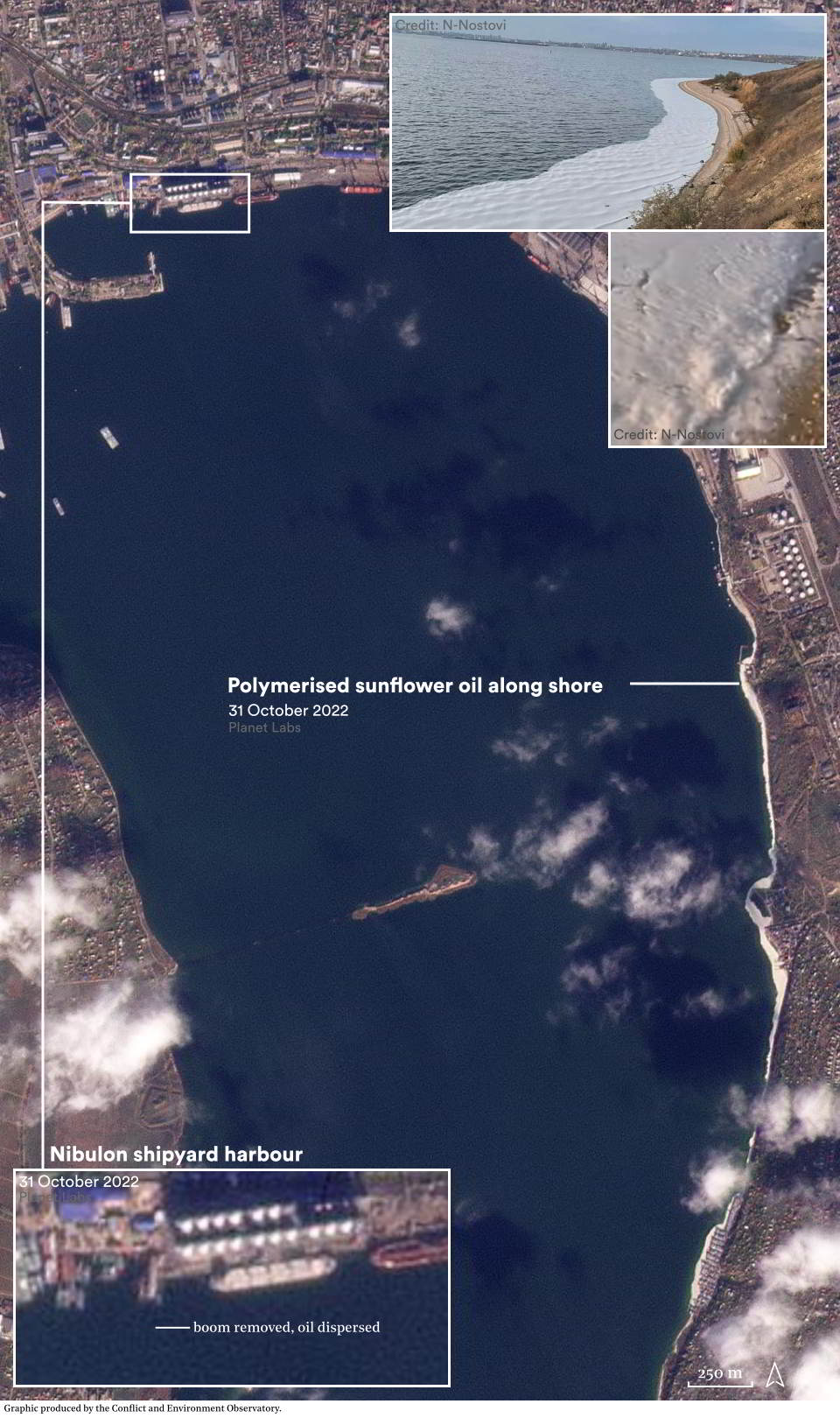

Following an attack by three drones on the night of 16th October at the Everi terminal, two tanks of sunflower oil began leaking and were set ablaze, requiring a major firefighting effort. The following morning local reporting showed oil and firefighting materials overflowing into the adjoining streets and then into storm drains, whilst footage from officials indicated the tanks continued leaking. Satellite imagery captured the first discharge of this pollution from the harbour at the Nibulon shipyard and into the Buh estuary, creating a slick of approximately 2 km2.

A boom was installed to contain the spread, as is visible in satellite imagery from 18th October, but this was removed some time after the 26th October, resulting in a second discharge of pollutants. Local media reported on 29th of a “thick, greasy foam, and birds dying on the shore” with accompanying footage of a white substance bordering the shoreline. This was clear in satellite imagery on 31st October, the next cloud free day, along a 3.5 km stretch of coast, and the following day more deaths of marine-life were revealed.

Satellite imagery shows a further build-up of pollutants at the harbour at the Nibulon shipyard between 1st and 12th November, and then their release into the wider estuary on 15th. This marked the third and final discharge, after which tidal flows transported the pollution to upstream beaches, once more reported by local media.

Perhaps the boom was removed based on the misconception that sunflower oil is non-toxic, harmless and biodegradable in the marine environment, and it will simply sink to the riverbed. This assumption is known to be incorrect because of the dramatic case of the MV Kimya, which sank off the coast of Anglesey in Wales in 1991. Divers opened the valves on the sunken tanks with the assumption that the 1,500 tons of sunflower oil would nourish marine bacteria – but instead it caused an environmental disaster. Agitation by waves caused the oil to polymerise, rise, reach the shoreline and form a concrete-like aggregate, capping off any creatures below. A legacy was even reported more than 25 years later.

The photo and video footage from the ground indicates the same polymerisation has occurred in the Buh estuary, owing to the turbulent tidal mixing. This hypothesis explains any confusion as to why some of the slicks appear white. In addition to the oil, there was additional contamination from the aqueous film forming foams used in fire fighting – these are known to have significant ecotoxicity, especially for aquatic species, and because of their environmental persistence they bioaccumulate.4

The unfolding Everi terminal sunflower oil spill from space, scroll left to right to view changes over time.

Outlook

The ecologically sensitive Buh estuary has suffered as a result of the conflict and, given its proximity to the current frontlines, it is threatened from the consequences of further attacks, particularly in the Mykolaiv area. There are also threats from elsewhere in the basin and not covered here, such as the South Ukraine Nuclear Power Plant, which was targeted in September and sits upstream. Like other marine areas, there is also a risk from UXO and sea mines, especially if shipping traffic resumes, as is expected.

When conditions allow it is important that there is a proper characterisation of the impacts and ongoing risks based on ground-based measurements and detailed assessments. In particular ensuring the safety of the Alumina Refinery and MV Banglar Samriddhi seem to be high-priority tasks. There are significant challenges associated with supplying Mykolaiv with water, especially if its 200,000 refugees return, and it is likely these will have some impact on the estuary.

Immediate and future needs

Coastal and marine habitats can be highly vulnerable to physical damage or pollution. Protecting them is not just important for biodiversity but also for the numerous ecosystem services they provide, from fisheries to protection from extreme weather events. Historically severe environmental degradation in the Black and Azov seas make it all the more important to ensure that their remaining ecosystems are protected, and that the harms already caused by the armed conflict are identified and addressed.

i) Minimise harm to coastal and marine habitats

Conflict parties should ensure that risks to the coastal and marine environment are fully considered in operational planning and that precautions are taken in prosecuting attacks on terrestrial and marine objectives.

ii) Target enhanced support to help identify harms

The challenge of monitoring and assessing direct and indirect harms to terrestrial biodiversity and to marine ecosystems from incidents linked to armed conflict justify both a precautionary approach to military activities but also enhanced international cooperation in support of researchers and conservationists. This should include international support to assess the impact of the conflict on cetacean populations, and to rebuild fisheries governance.

iii) Map and address hazardous wrecks

Wrecks can become persistent sources of pollution into the coastal and marine environment. Steps should be taken to identify and record new wreck sites and, where possible, assess and monitor the potential risks they pose to coastal and marine habitats and resources.

iv) Map and address land-based pollution sources

There are now numerous locations where damaged industrial, commercial or energy facilities, and critical civilian infrastructure, have created ongoing pollution risks for the coastal and marine environment. These sites should be identified, assessed and, where necessary, prioritised for early intervention to contain pollution sources or prevent the offsite movement of pollutants.

Media enquiries: doug(at)ceobs.org or nickolai.denisov(at)zoinet.org

Research and content by CEOBS and Zoï Environment Network.

Our thanks to our reviewers: Bo Libert UN-OSCE expert, Uppsala; Kostiantyn Demianenko, Institute of Fisheries and Marine Ecology of the State Agency of Fisheries of Ukraine, Kyiv; Olena Kovalenko, OSCE expert; Galyna Minicheva and Yevhen Sokolov, Institute of Marine Biology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Odesa.

Cartography and graphics: Matthias Beilstein, Zoï Environment Network, Schaffhausen.

- ACCOBAMS provide non-extrapolated figures, while Ukrainian researchers base their assessment on extrapolation methods.

- The refinery is one of the largest non-ferrous metallurgy facilities in Europe, one of the largest employees in the area, and until February was run by the Rusal company, which is owned by the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska. Close to Vladimir Putin, he was placed under international sanctions and the refinery was seized by the Ukrainian courts in May, and taken into state ownership in January 2023. Against this legal backdrop, some staff have remained working unpaid and in dangerous conditions, all to ensure critical processes – this represents a more hidden risk to the safety of the site.

- Damage from the satellite imagery is consistent with footage uploaded to YouTube showing a leaking caustic soda tank.

- Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “forever chemicals”, are a group of globally prevalent compounds with a potentially huge ecological and environmental health consequences that scientists are only just starting to fully understand – see Kurwadkar et al., (2022) for a review of the current state of our understanding of PFAS. A short review on the ecotoxicity specifically for marine species can be found in Pozo et al., (2022), which also describes a partly analogous event – release of firefighting foams into the Port of Santos (Brazil) following a fire at a petrochemical terminal. Even if supposedly less toxic alternatives were used – short-chain perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) – these are now also thought to be equally problematic.