2. Water

Published: September, 2022 · Categories: Publications, Ukraine

This is the second in a series of thematic briefings on the environmental consequences of the armed conflict in Ukraine, jointly prepared by the Conflict and Environment Observatory and Zoï Environment Network. This work is supported by the United Nations Environment Programme as part of its efforts to monitor the environmental situation in Ukraine, and is co-financed by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Situation

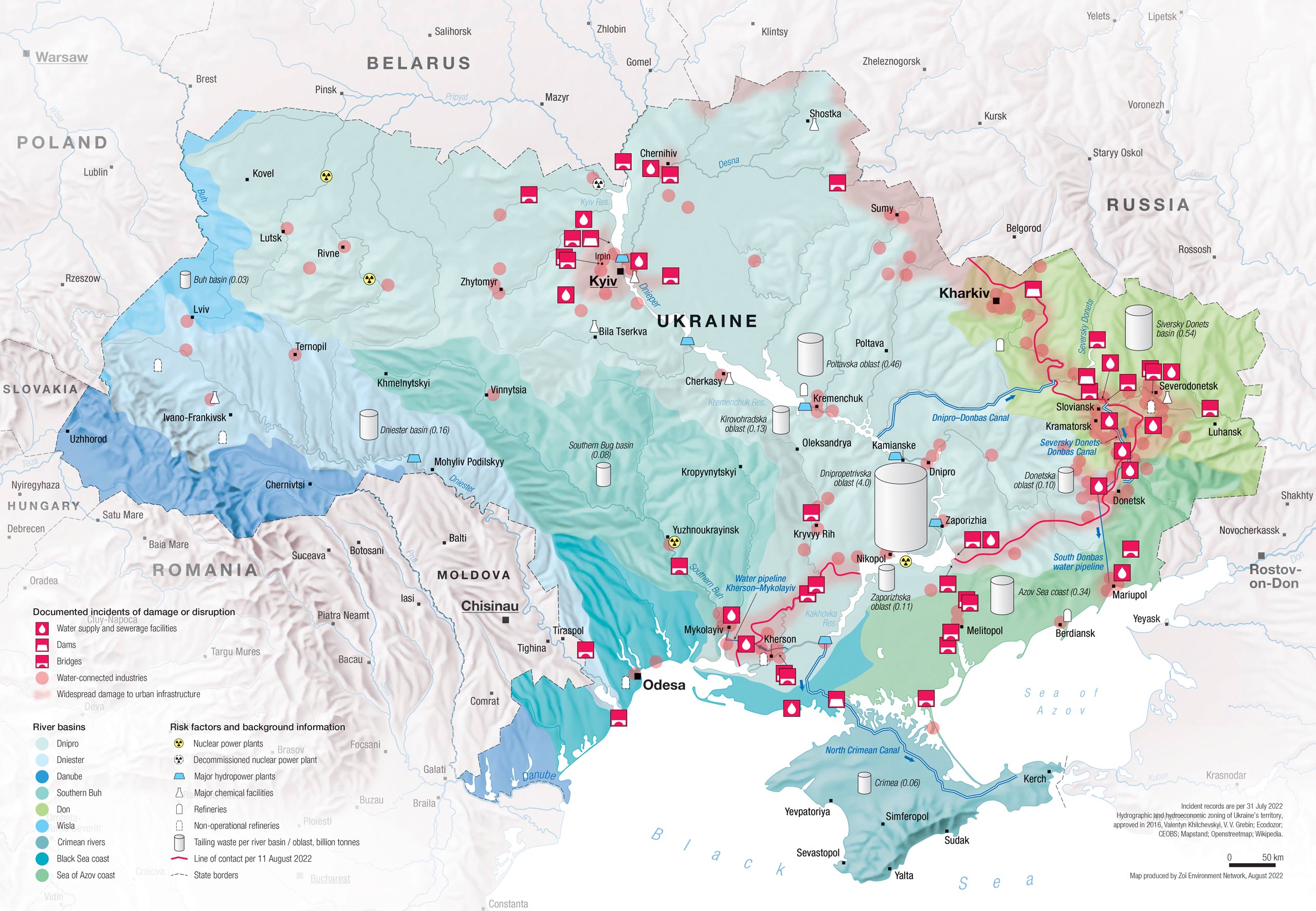

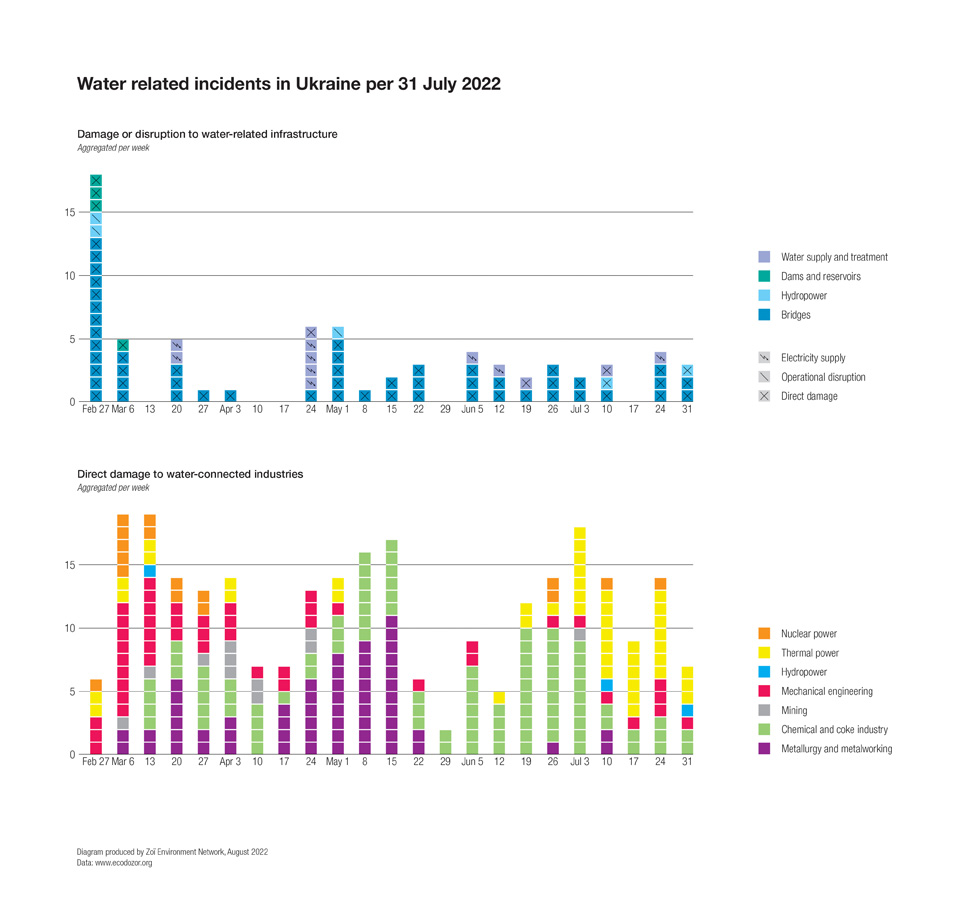

The conflict in Ukraine has impacted water supplies and resources in a number of ways. This includes disruption to domestic supplies, and damage to the highly developed infrastructure that supplies energy, industrial and agricultural users. Disruption and damage to water infrastructure can lead to pollution incidents and this has generated concerns about water quality. Pollution has also resulted from the conduct of the fighting itself. Water and water infrastructure have been repeatedly targeted for their strategic value. In addition, many industries that are dependent on water, or whose operations have the potential to impact water quality when disrupted, have been damaged during the fighting.

Contents

Overview and key themes

Water supply

Water is an object indispensable for the survival of the civilian population, and water infrastructure and resources are civilian in nature and should be protected. Occupying powers have an obligation to ensure the provision of water. Nevertheless, the UN has estimated that by August 2022, 16 million people in Ukraine needed assistance with water, sanitation or hygiene, and 1.4 million people in eastern Ukraine lacked access to piped water.

Already in a difficult situation owing to damage from the fighting since 2014, today some towns and cities in Donetsk Oblast receive piped water for only a few hours once or twice a week or, as in Sloviansk, there is only a single set of pumps for those who remain. Such is the desperation, the authorities have even had to warn people against drinking the water in mine tailing ponds. In Mariupol there have been reports of sewage contaminating drinking water, and the restoration of supply infrastructure and wastewater disposal is now thought to be impossible in some districts. The Voda Donbassa water company, which supplies Mariupol, has been silent since May, despite having worked across the line of contact to repair damage since 2015. Elsewhere, other examples of coping strategies include in Mykolaiv, where it was reported that people resorted to using river water.

Exploring reported damage and disruption to water infrastructure and supplies as a result of the conflict in Ukraine, and industrial risks associated with water bodies. Click to expand.

The loss of water supplies has been caused by both direct and indirect damage and disruption. There have been many instances of damage to water towers, pipelines, sewage pipes and pumping stations. These have often been associated with the use of explosive weapons in urban areas. Major facilities have also been impacted. One notable example is the Popasna site near Bilohorivka, northern Luhansk, which was targeted on multiple occasions in May, with damage sustained to the filtration station, lift station, and electrical equipment. According to the regional governor, Serhiy Haidai, the damage to water facilities near Bilohorivka would leave one million people without water, and was impossible to fix with the conflict ongoing. Elsewhere, key facilities remain de-energised due to hostilities, such as the Donetsk and Karlivska filtration stations.

At least four dams and reservoirs have sustained direct damage. The Oskil Reservoir on the Siversky Donets River near Izyum had its gates destroyed on 31st March. The reservoir, the eighth largest in Ukraine, rapidly emptied, raising downstream river levels. The need to repair and restore the reservoir has been contested on the grounds that there may be more ecosystem service gain from fully restoring the natural course of the river. Fishermen hope that the destruction of these larger scale facilities may actually help migratory fish populations recover.

Water quality

As well as water supply interruptions, some locations have seen a decline in water quality. Attacks or disruption to wastewater treatment infrastructure have been reported in Chernihiv, Mariupol, Mykolaiv, Rubizhne, Skadovsk, Sloviansk and Vasylivka. In the case of Vasylivka and Mykolaiv, there were wastewater discharges into the Dnipro River that were visible from space.

The flooding of sewage into the streets in Mariupol represents a health risk, especially because people are reportedly using this water to wash and clean in, even if the risk from cholera is thought to be overstated. Following the loss of access to piped water, there are reports across the country of people turning to wells. Groundwater already meets about 25% of Ukraine’s drinking water needs, yet in places it is heavily contaminated. Aquifer contamination is likely to be exacerbated by pollution linked to the conflict, this is particularly true of the pre-existing problem of abandoned coal mine flooding in the Donbas region. Even before 2014, groundwater monitoring by industrial enterprises was underdeveloped.

Given the scale of the damage to industrial, agricultural and residential buildings and facilities, there is likely significant surface runoff of pollutants into waterways across the country. This remains uncharacterised, although to some extent may be offset by the reduction in industrial activity. Other pollution hotspots are associated with the conduct of the conflict, for example contested river crossing points where large volumes of damaged vehicles are present. One such location where heavy contamination is likely is near the repeated and failed crossings of the Siversky Donets by Russian troops in May. The strategic destruction of bridges can contribute to pollution levels and disrupt the flow of rivers.

| Key incidents at selected water facilities, Feb – Aug 2022 | |

|---|---|

| Facility | Incidents |

| Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant. | Dam occupied by Russian forces at the outset of the conflict to secure access to the source of the North Crimean Canal. The dam blocking flow into Crimea was blown up. Areas at or near the HPP were shelled on several occasions in July and August. |

| Kyiv Hydroelectric Power Plant. | Russian troops sought to occupy the Kyiv hydroelectric power plant in the early days of the conflict. A dam failure or abnormally high discharge could have threatened low-lying areas, even if the water levels could have been partly controlled by downstream dams on the Dnieper. In March a helicopter was shot above the HPP reservoir. |

| Popasna Water Pipeline and the Siversky Donets - Donbas Canal. | Multiple damaging incidents to pumping stations in April-May. |

| Slovyansk Water Filtration Station and Sieverodonetsk sewage facility. | Shelling in June-July. |

| Mykil's'ke to Mykolaiv pipeline. | Damage to the pipeline that pumps River Dnipro water to Mykolaiv in mid-April has left the city without potable water. |

| Irpin dam and pumping station. | Destruction in February leading to flooding (see the case study below). |

| Water supply facilities in: Kyiv Oblast (Bucha, Brovary, Ivankovo); Vasyliv Water and Sewage Facility; Karlivska Water Filtration Station; South Donbas Water Pipeline Pumping Station; Mayatsk Pumping Station. | Multiple disruptions to energy supply. |

Water as a military tool or objective

There are numerous cases where water infrastructure has been used for military or strategic purposes. The Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant near Kherson was captured on the first day of the conflict. This was no coincidence, as it is also the location where the North Crimean Canal joins the River Dnieper. The canal is the main source of water to the arid peninsula, and has been the focus of intense transboundary hydropolitics since 2014 when it was blocked by Ukraine in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea. On the 24th February the dam was blown up, and the next day it was reported that maintenance work had started on the pumping stations required to overcome the gradient to Crimea. The Russian-backed authorities in Crimea had come under acute domestic pressure over water supplies and control over the canal remains a high political priority for Russia. Nevertheless, satellite evidence suggests that there is some way to go before Crimea’s water budget returns to its pre-2014 state.

The occupied Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant has itself sustained damage from the conflict. In May, there was a scare that damage or intentional mismanagement may have led to uncontrolled flooding. However, in retrospect experts summarised it was just the passing of a naturally high spring flood, and modelling indicated the risk of flooding to be low. In July and August, further attacks to prevent the use of the dam as a military crossing point were reported. The nearby Antonivka Road Bridge is one of more than 50 bridges that have been damaged across Ukraine. Hydropower will be an even more important power source this winter but is not only threatened by the conflict, but also by the climate. In July, drought led to the lowest flow rates into the Dniester Reservoir since its creation in the mid 1980s, reducing electricity production at a critical time.

Case study: Flooding in the Irpin river valley

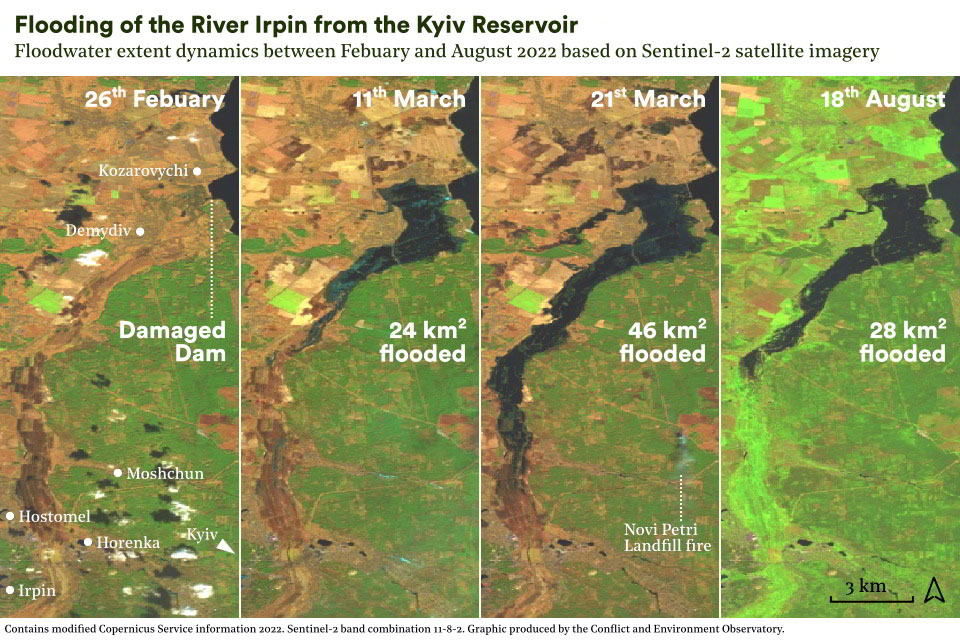

On the afternoon of 26th February the dam between the Irpin River and the Kyiv Reservoir was damaged. In the subsequent days, weeks and months, floodwater accumulated in the Irpin river valley, flooding the towns of Demydiv and Kozarovychi, and causing civilian hardship. It is claimed that the flooding helped in the defence of Kyiv, and the story was covered widely, including in the international press.

The Irpin River has undergone considerable canalisation and hydro-engineering since the 1950s, with water now having to be pumped three metres higher into the Kyiv Reservoir. It was because of this difference in water levels that water flowed rapidly up the Irpin river valley after damage to the dam.

Flooding extent

The extent of the flooding was first visible in satellite radar imagery on 28th February. It grew rapidly, reaching approximately 20 km2 by 17th March. By 19th March, properties in Demydiv were flooding, in particular the basements people were sheltering in, prompting efforts to pump water back into the Kyiv Reservoir. The floodwater grew to a maximum extent of approximately 46 km2 around 21st March, reaching just south of the town of Moschun. The floodwaters have receded from their maximum extent in recent months to a more stable level – 28 km2 as of 18th August.

Environmental consequences

Potential pollutants present in the flooded settlements include sewage from household latrines, fuel and lubricants from petrol stations, construction materials from building sites, paints from a metal shop, and heavy metals from electrical infrastructure. If floodwaters rise further, potential pollution sources could include landfills, factories and sawmills, however the majority of homes and industrial units lie a few metres above the maximum water level.

The valley is littered with military materiel, particularly from failed river crossing attempts by Russian troops. At least 12 tanks, four heavy vehicles, pontoon segments, and countless craters are visible on online footage, and there is likely a significant presence of mines and unexploded ordnance. Some of the most intense fighting took place in the urban areas in the basin: Hostomel, Irpin and Moschun.

Pollution arising from the destruction of buildings, industry and military materiel may be mobilised into the floodwaters by surface run-off. Damaged military vehicles and equipment will release harmful pollutants including heavy metals, motor oil and fuel, persistent organic pollutants like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), alongside explosives, which have varying degrees of toxicity and environmental persistence.

Drone footage of damaged and burned out military materiel in the Irpin valley.

The floodwaters cover a large area of agricultural land. If they subside, the soil will likely be contaminated with pollutants, such as heavy metals and PAHs. Some researchers have also been concerned that any soluble fertilisers and pesticides used may now be dissolved in the water. The flooding will likely lead to further contamination of already polluted groundwaters, which are an important water source in rural settlements, even near Kyiv.

The wetlands along the Irpin are a biodiversity hotspot, albeit one that was in decline pre-conflict, and a protected area as part of the Emerald Network. The valley has four grassland and meadow habitat types and is home to many fish species and migratory birds, including vulnerable species like the red-footed falcon and lesser white-fronted goose. These are all threatened by the contaminated flood water, but assessing the magnitude of the threat requires in-situ measurements.

The return of water to the valley may not be the rewetting that some conservationists had long advocated for. It was a quick process, without the planning usually required for successful ecological restoration. Take the example of fish – invasive species will be introduced from flooded fish farms and from the Kyiv Reservoir, whilst the habitat for species that prefer flowing water is now reduced. In the case that all floodwater is pumped out, it is estimated that it would take at least five years to return to a similar ecological state.

Mythology

As the flooding became visible, reporting on social media and traditional media framed the rising water as a deliberate military strategy by Ukrainian troops to protect Kyiv. This was in contrast to the initial local media reporting, which blamed Russian attacks. The Ukrainian authorities initially denied any damage to the dam, but two days later the Office of the Prosecutor General reported that the pumping station had indeed been destroyed by the Russians. Notably, there had also been a failed attack on the dam the previous night, according to the Ukrainian Ministry of Infrastructure. The Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine shared the view that the damage was caused by Russian troops.

The controversy grew in April, with Ukrainian ecologist Volodymyr Boreyko coining the term ‘hero river’. This idea was internationalised by The Guardian, which with the New York Times and Reuters reported that Ukrainian troops opened the sluice gates – something also claimed by a technician at the pumping station. Press photography, videos, drone footage and very high resolution satellite imagery have subsequently confirmed significant damage to the southern section of the dam, indicative of explosive damage, and this is where the water can be seen flowing into the Irpin. A Ukrainska pravda and later Reuters article reported that the dam was blown up by Ukrainian troops, quoting the regional governor, Oleksiy Kuleba. This makes more logical sense, given that the dam represented the last bridge over the Irpin, hence forcing Russia to construct pontoon bridges – as was reported the following day in Demydiv.

What next for the Irpin river valley?

Before the conflict, the ecology of the valley was at severe risk from development. This was strongly opposed by local civil society, who alleged that the developments were unlawful, had been undertaken without an environmental impact assessment, and that the responsible authorities were negligent, or worse.

By late August, it was reported that the dam had been repaired and that water had begun to be pumped out of the Irpin valley. It is an open question if there will be a return to the previous level of development. The alternative solution is to start managing the floodwater in a nature-positive way – this is likely to have many benefits and ecosystem services, such as increased carbon sequestration as peat recovers, and reduced air pollution through fewer peat fires.

Immediate and future needs

Water infrastructure is indispensable to the civilian population and its destruction or mismanagement by or for military means increases human suffering and risks serious environmental harm. All conflict parties must take immediate and urgent steps to prevent further damage to water infrastructure and to address the harm already caused. Priority measures include:

Restoration of supply

Conflict parties must facilitate humanitarian access to restore access to drinking water through alternative sources and to allow the repair and restoration of water infrastructure.

Demilitarisation of water infrastructure

Conflict parties must withdraw military forces from critical water infrastructure, including hydroelectric power plants, in order to reduce the risk of severe incidents and to help minimise damage to such sites.

Safety and emergency preparedness

Urgent and ongoing safety inspections are needed for critical water infrastructure and hydroelectric power plants to assess the environmental and humanitarian risks associated with conflict-mediated damage and disruption. Inspections and preparedness planning should also be extended to environmentally hazardous infrastructure in proximity to waterways and aquifers, including nuclear and industrial facilities, and tailings dams.

Data collection on impacted sites

Data collection on water pollution and damage to freshwater ecosystems caused or exacerbated by the conflict should be initiated as soon as is practicable after the incident, where possible in-situ water sampling should be undertaken to support data collected remotely.

Media enquiries: doug(at)ceobs.org or nickolai.denisov(at)zoinet.org

Research and content by CEOBS and Zoï Environment Network.

Additional contributors: Dmytro Averin, Zoï Environment Network, Irpin; Oksana Huliaieva, Kyiv; Iryna Nikolaieva, PAX, Utrecht; Miguel Madrid, Granada.

Cartography and graphics: Matthias Beilstein, Zoï Environment Network, Schaffhausen.