Examples of environmental harm in Ukraine | return to map

Name: Azovstal Iron and Steel Works

Location: Mariupol, Donetsk Oblast

CEOBS database ID: 10157

Context

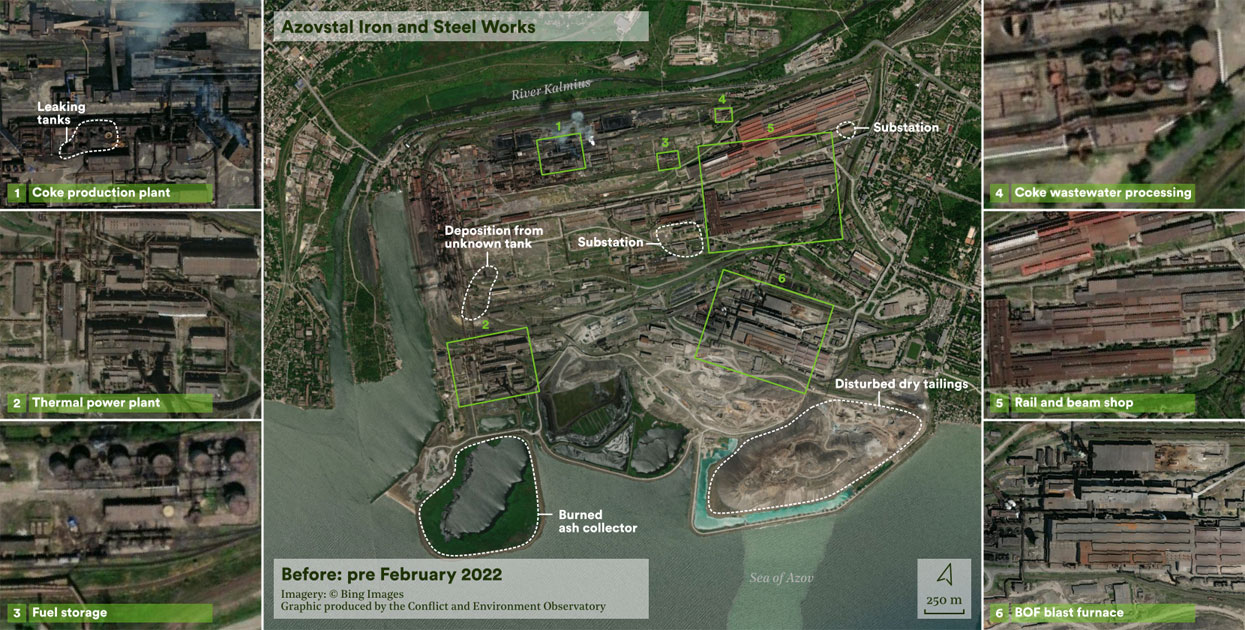

Established in 1933 and located in the heart of Mariupol, the Azovstal site faces the Sea of Azov on the left bank of the River Kalmius, and occupies 11 km2 – approximately 10% of the city’s urban footprint. Prior to February 2022, Azovstal was one of Ukraine’s largest steel producers, employing more than 10,000 people, and specialising in the manufacture of high-quality rolled products for machine building. Production was an important part of Ukraine’s economy, accounting for nearly 4% of Ukraine’s exports to more than 50 countries and 0.5% of GDP. However, this vast industrial output has been accompanied by a legacy of environmental pollution whose risks have been greatly exacerbated by damage sustained during the campaign to capture Mariupol in 2022.

Timeline of key incidents

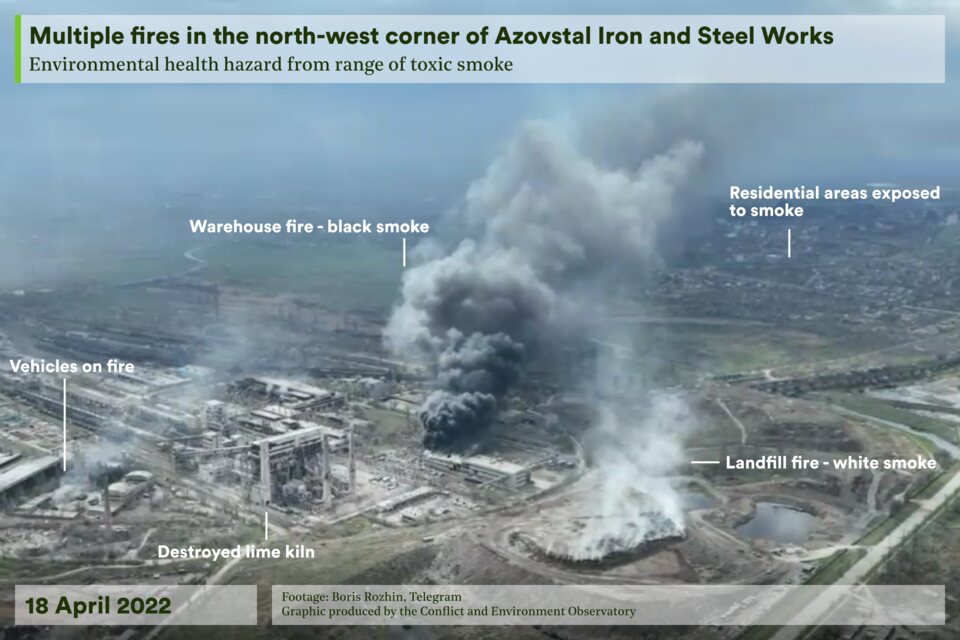

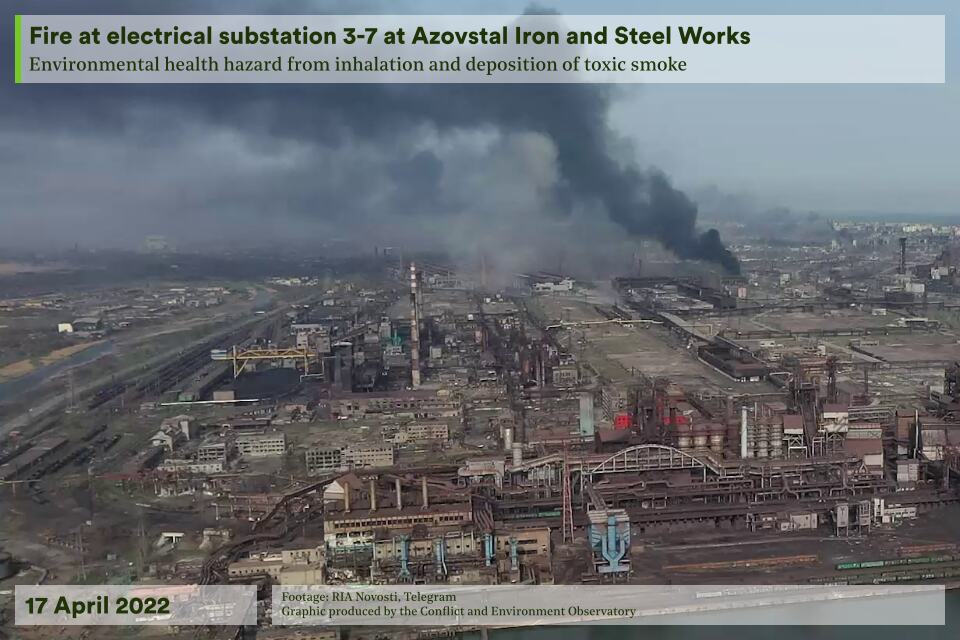

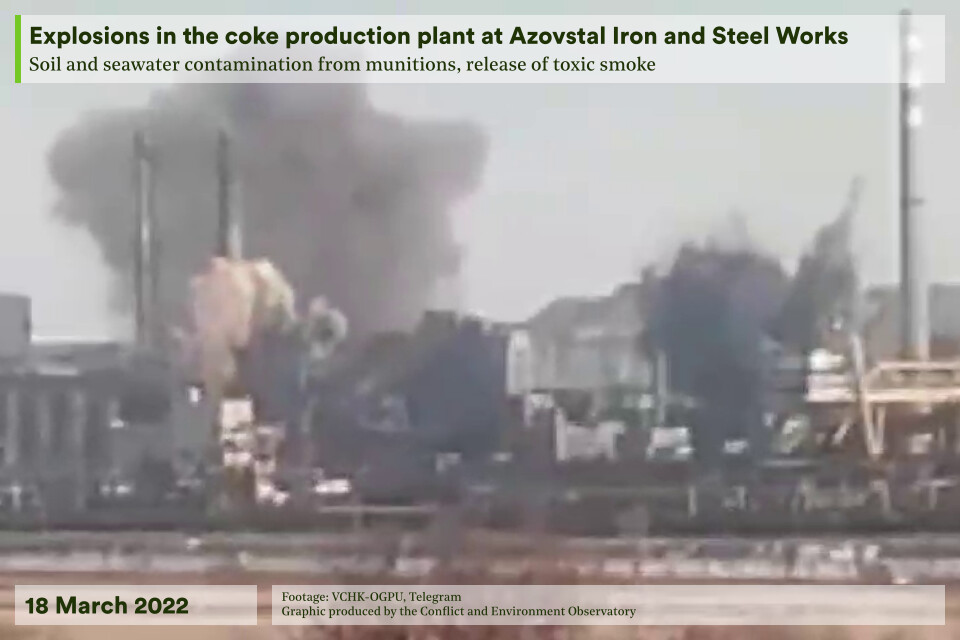

Mariupol was completely surrounded by the 2nd March 2022, and suffered intense shelling. Analysis of satellite imagery reveals that damage was first sustained at Azovstal before the morning of the 9th March; but it was video footage of two large fires on the 18th March that sparked widespread coverage and fears over the environmental consequences. Between late March and April, the Russians advanced through Mariupol, forcing Ukrainian troops to fall back and defend from ever-more isolated positions. After the capture of the Ilyich Metallurgical Plant, also in Mariupol, on the 15th April, all remaining Ukrainian forces retreated to Azovstal, where what became known as “The Last Stand at Azovstal” lasted 29 days until the 17th May.

During the month of the siege, aerial bombardments occurred almost daily across the entire premises, alongside attacks from ground forces. The attacks were intense: for example, overnight on the 25th-26th April, at least 35 airstrikes were carried out, causing a fire at the blast furnace and widespread casualties. As well as soldiers, more than 300 civilians had sought protection in Azovstal, with evacuations only facilitated for the first time on the 1st May.

Damage assessment

The fighting resulted in the near-total destruction of the vast Azovstal site. Remote assessment of this damage has been performed using multiple methods. Analysis of very high resolution (VHR) satellite imagery from the 25th April 2022 by UNOSAT identified 214 impact craters, although this is certainly an underestimate as many more airstrikes occurred after this date and are visible in VHR satellite imagery provided by Google Earth. Other satellite sources detected 52 fires at the site during the siege,1 again likely an underestimate due to persistent cloud cover. In total, CEOBS’ analysis of social media and satellite imagery recorded 87 instances of direct damage to the site since the 9th March 2022.2 Finally, analysis of Synthetic Aperture Radar damage mapping shows that at least 57% of built structures at the site have been damaged.3

Environmental harm assessment

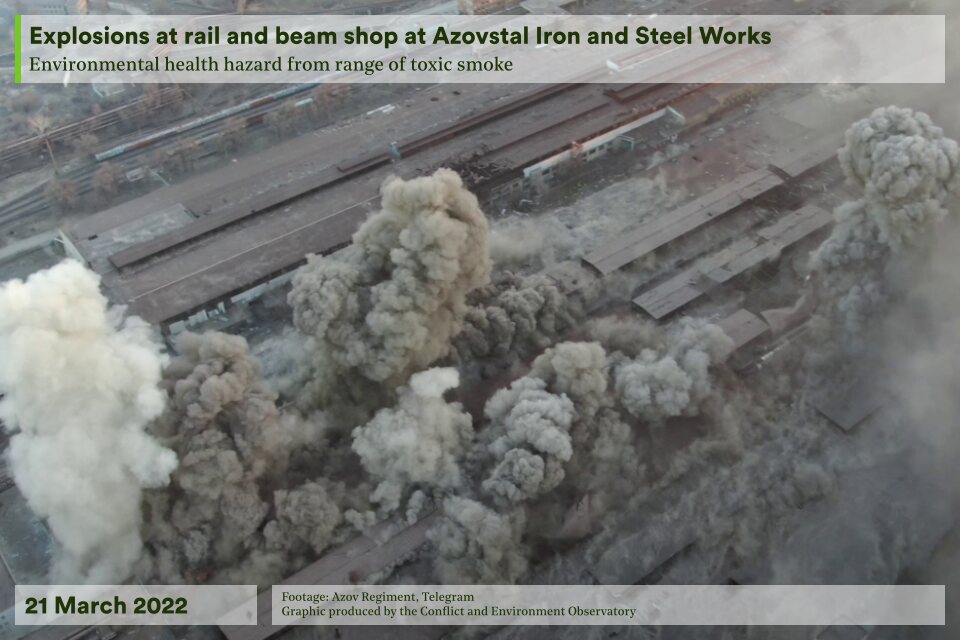

Significant hazards to environmental health arose during the siege from damage to many parts of the facility, including blast furnaces, coke production areas, electrical substations and wastewater treatment facilities. Some of these instances of damage are highlighted in the map above and the imagery below.

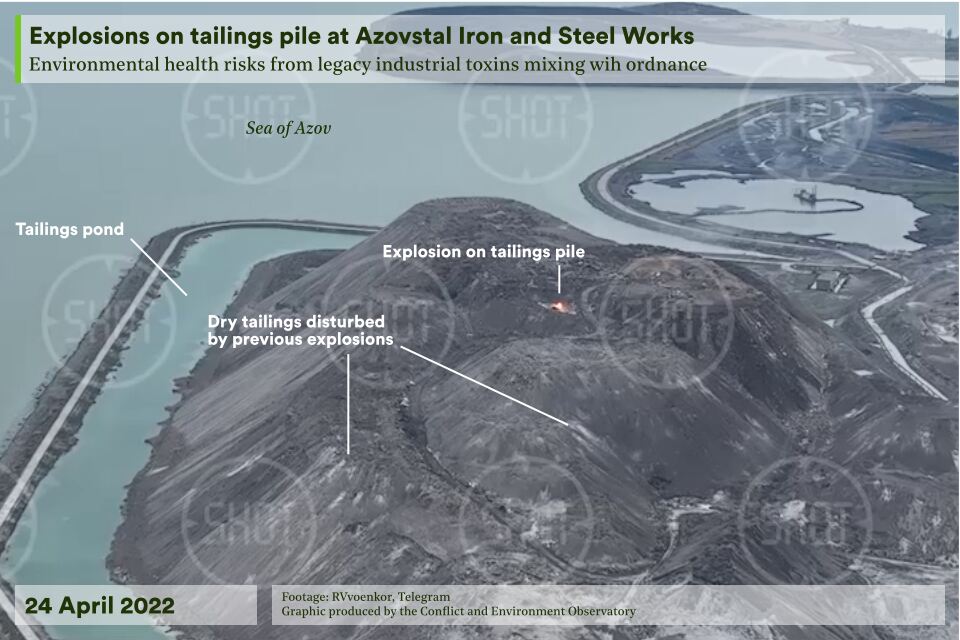

After nearly a century of use for iron and steel production, the site had pre-existing pollution problems that had been compounded by weak historic environmental mismanagement. Legacy pollutants from industrial activity at Azovstal are likely to include various heavy metals (including lead and arsenic) alongside sulphates, nitrates, and hydrocarbons, which had been shown to exceed maximum permissible concentrations.4 The environmental threats caused by such pollutants will have been exacerbated by the fighting; this includes the release of asbestos from some buildings. Without intervention, the spread of these contaminants onto bare soil, alongside observed mixing with seawater in the Sea of Azov, the vast amounts of debris in the River Kalmius, and likely groundwater contamination, will further pollute the local and regional environment for years to come.5

Air pollution from the burning of hazardous materials and hydrocarbons stored at the site, alongside the resuspension of hazardous dust from explosions and fighting, was a major concern. Despite this, satellite measurements indicate that average air quality above Mariupol improved during the period of the siege.6 The cessation of iron and steel production at the plant may be responsible for this: prior to the invasion, Mariupol was one of the most polluted cities in Europe in terms of air quality, and Azovstal was the 7th largest single emitter of pollutants in Ukraine.

Longer-term implications

The environmental harm caused by the destruction at Azovstal is already substantial and complex. The ongoing occupation of Mariupol, prevents an independent field assessment of the extent of pollution at present.7 However, video footage from Ukrainian sources remaining in Mariupol indicates that Azovstal has been left to decay.8 This lack of governance has already resulted in numerous instances of environmental damage;9 the longer-term impacts of this mismanagement may be catastrophic.10 Moreover Azovstal was just one of numerous hazardous industrial facilities in Mariupol, this includes the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works, which also presents serious risks to the environment and public health.

Representatives of the self-styled “Donetsk People’s Republic” have sought to spin pre-war environmental pollution from Azovstal as a justification for not beginning remedial activities, although they suggested in 2023 that Azovstal would be converted into a ‘technopark’.11 If the de facto authorities do redevelop the site, they will be contending with a legacy of environmental contamination worsened by the siege in 2022.

Dis/mis-information watch

The tailings ponds at Azovstal have been the subject of several cases of misinformation: the day after the siege ended, social media stories of marine pollution from the tailings ponds, accompanied by images of the ponds glowing a luminous green, were spread widely online. These images were later shown to date from several years earlier. More generally, the future of Azovstal has been widely used in pro-Russian media as a propaganda tool, with many different future development scenarios discussed, though none have yet materialised (see footnotes 8 and 11).

External resources

Ukraine conflict environmental briefing: Industry | CEOBS and Zoï Environment Network

Azovstal Iron & Steel Works | Global Energy Monitor

Too big to fail. Will Rinat Akhmetov be able to rebuild a metallurgical empire? | Forbes.ua

Sustainability Report 2020 | MetInvest

Mariupol or Akhmetovsk? Air Pollution in Donbas Report 2020 | Arnika, Clean Air for Ukraine

“Our City Was Gone”: Russia’s Devastation of Mariupol, Ukraine | Human Rights Watch

Return to the country map here.

- On the two VIIRS instruments onboard the S-NPP and NOAA-20 satellites.

- This value represents the number of times that we identified damage at a site caused by military activity, either via footage or satellite data of an airstrike or a fire, or by comparing imagery before and after damage was recorded, as recorded in our database of environmental incidents operated since the beginning of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- This was calculated by analysing the intersection between built structure polygons, obtained from a combination of OpenStreetMap and Microsoft Buildings, and damage mapping produced by Jamon Van Den Hoek (Oregon State University) and Corey Scher (City University of New York), derived from Sentinel-1 data. Visual inspection of very high resolution satellite imagery shows that this method underestimates damage.

- A 2017 study identified that the near billion cubic metres of wastewater produced annually contained high levels of chlorides, sulphates, phenols, petroleum products and nitrates in excess of maximum permissible concentrations. A 2018 study also found exceedances of maximum permissible values of petroleum products, total iron, ammoniacal nitrogen and nitrites, and identified sewage outlet no. 9 as having the most significant exceedances. This outlet discharges waste from the sludge accumulator, where waste accumulates from the sinter, blast furnace and rolling shops.

- A study published in 2019 found waste outflow from Azovstal to be the single biggest source of pollution into the Sea of Azov. Biotesting of the Kalmius before and after the Azovstal outflows for a 2014 study showed an increase in death of the biomarkers, Ceriodaphnia crustaceans, and that the wastewater discharged exhibited lethal toxicity. Meanwhile, water pollution has also been visually identified in footage on social media and historical satellite imagery.

- Unfortunately, the loss of ground-based air quality measuring instruments early in the siege means that no direct measurements are available; however, the broader impact of the early phases of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on air quality have been investigated with remote sensing data, showing agreement with our earlier analysis.

- In terms of quantitative indicators, it seems unlikely that there is good baseline data for a historical comparison: a manuscript published in 2019 stated that there was an insufficiently developed monitoring system, without systematic measurements of water quality indicators.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kANOCfUEY9Y; https://www.youtube.com/shorts/lnSMi0Ms0OM; https://t.me/andriyshTime/9643; https://t.me/andriyshTime/9711

- These include a fire at a landfill within Azovstal on 12th June 2022.

- For instance, collapse of the barriers around the tailings ponds would cause both liquid and solid waste products from steel production to mix with seawater on an unprecedented scale: Ukrainian media offered a detailed analysis of the threat posed to the Sea of Azov by the tailings ponds.

- There have been competing statements by pro-Russian actors over the future of Azovstal. Although Denis Pushilin, the DPR head official, originally indicated that the plant would not be restored, ostensibly due to opposition from residents (though more likely because the scale of destruction was too great and they lacked the expertise), he later signed off on a plan to develop an industrial park and ‘environmentally friendly smelting’ at Azovstal. Conversely, the Russian-installed mayor of Mariupol, Konstantin Ivashchenko, suggested that Azovstal could become a ‘small modern enterprise’. The Russian Ministry of Construction, Housing and Communal Affairs, meanwhile, proposed several possible futures for Azovstal, including full restoration of production; creation of a ‘modern urban business centre’; development of new green space, including a marina, botanical gardens and memorial park; and finally new green space alongside coastal and river tourism zones.