Trump’s destruction of USAID and reductions in humanitarian and development budgets in favour of military spending in Europe have had a devastating impact on the sector.

Catalysed by the new US administration entering office, there has been an unprecedented reconfiguration of global political attitudes towards the humanitarian-environmental sector. In this blog, we document the ramifications of these changes as recorded in a community survey and online meeting in collaboration with the Environmental Peacebuilding Association.

Introduction

The Trump administration’s January 2025 decision to freeze all foreign assistance funding has had massive and reverberating consequences for humanitarian, development and conservation programmes in areas affected by conflicts and fragility – for example, leading to thousands of job losses from humanitarian mine action programmes and halting emergency food aid in Sudan. Since then, the UK government has followed the US’s lead, cutting foreign aid by around £6 billion to fund increased defence spending. Other European and NATO countries, including France, Sweden and the Netherlands, have made similar moves to greatly reduce spending on direct foreign assistance at a time where there are more active conflicts than at any point since WWII.

Concurrently in the US, there have been freezes on US federal research grants, efforts to curtail public access to environmental and climate data, and widespread threats of cuts and further redundancies within environmentally-related federal departments.

CEOBS and EnPAx jointly convened an online meeting of practitioners, academics and civil society to document the impacts and implications of this new reality, first consulting them on their initial reactions in late February and early March.

Uncertainty and loss of funding across the sector

We received responses from 52 individuals and 10 organisations sharing how the cuts to foreign aid have impacted their work. The organisations represented were largely NGOs working across the issues of environment, humanitarian assistance, advocacy and research, with some representation from think tanks, research institutions, and faith-based and grassroots organisations. Individual respondents were a mix of academics, practitioners and consultants. No responses were received from donors.

Of the 62 respondents, 55% said they were significantly impacted by the new reality, while 45% said they were not impacted. This was somewhat surprising, and it is likely that our survey in fact represents a previous reality. In the meeting, we further surveyed the feelings of the group, and 66% of respondents said that the impacts on their work had worsened since completing the survey, with only 14% saying the impacts had remained the same or lessened. The majority of the individuals who originally said they had not been impacted were consultants or academics, rather than practitioners. All of the 70% of organisations who said they were affected were NGOs.

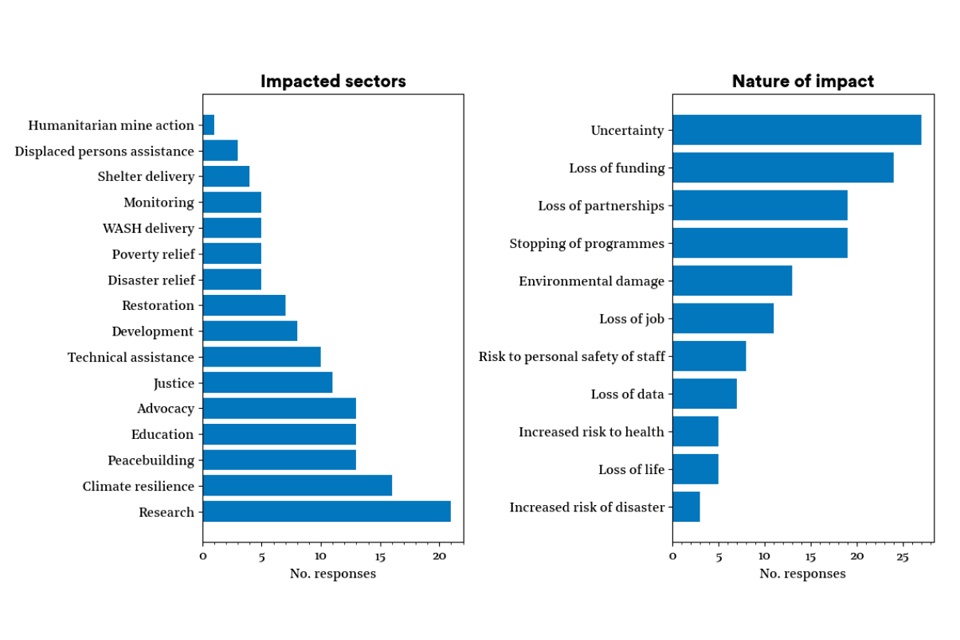

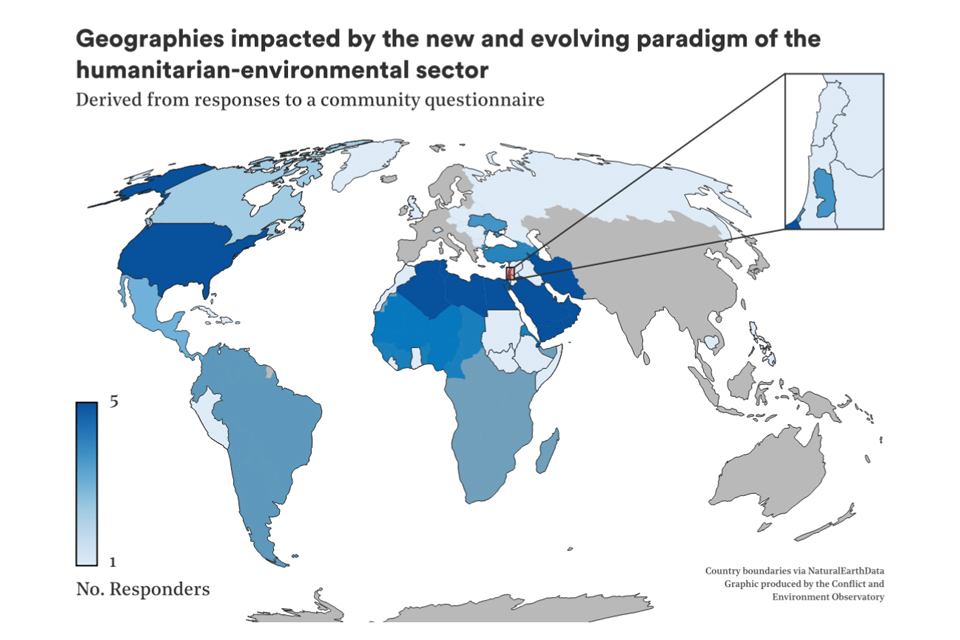

The sectors and geographies captured by the survey responses were skewed but wide-ranging. For instance, while the impacts on the research communities are clearly well captured, it seems surprising that only one respondent considered mine action to have been impacted — this presumably reflected a lack of individuals working on mine action completing the survey. In terms of geographies, most respondents felt that the impacts would be felt at multiple scales internationally. The Sahel and MENA regions were most frequently cited as the regions that would be impacted, followed by the southern Caucasus, Latin America, Western Africa and Eastern Europe. Specific countries were also mentioned, most frequently the US followed by Ukraine and Palestine.

Uncertainty and a loss of funding were widely cited impacts of the new reality, along with more visceral impacts such as loss of life and environmental damage, especially in those communities that were already most at risk. A loss of partnerships, knowledge and experience, and the breakdown of trust between organisations and collaborators, were also frequently mentioned. More broadly, many felt that the new reality would greatly reduce our capacity to think ambitiously about action on the environment, with universities likely to stop offering courses in environmental peacebuilding and climate action. However, it was also emphasised that even prior to the new US administration, a political realignment had already begun in many countries – for instance, the Swedish government had already more than halved its overseas aid budget in 2023. The cancellation of such programmes internationally without prior notice has led to greater competition within the environmental peacebuilding sector for ever-dwindling funding.

How do we forward as a community?

Our survey and the discussion in our meeting demonstrate that the consequences of the new political reality for our sector are stark. Jobs have been lost, programmes providing essential services to those in extreme need have been halted, and the collection and dissemination of data and knowledge is under threat. The challenges we will face to continue to provide a voice for conflict-affected people and environments will increase. This is why documenting exactly what is happening as thoroughly as possible is of paramount concern.

As we move forward, it will also be important to reflect critically on the work that we were engaged in. Prior to this period of change, despite the manifest need for our work, support was not always directed towards those in greatest need. Financial support in particular was often not offered within realistic timescales given the nature of work, and bidding processes were often unduly complex. Income diversification for NGOs is often also a major challenge.

To overcome all of this we will need to double down on working collaboratively across borders and disciplines. Solidarity and mutual aid is more important now than ever before, as is building new relationships and strengthening existing ones. Our StopGap represents an initial effort to respond, building online structures and networks to address the evolving needs of the sector.

Finally, we must acknowledge that what is a new reality for many in our sector has long been part of the daily existence of those in conflict-affected and colonised states, who are constantly forced to protect civil society space and overcome highly oppressive structures with greatly limited funds. How can we learn from each other and in the process build genuine solidarity?

Huge thanks to Erika Weinthal, Carl Bruch, Shweta Sanjeev and Mara Pusic from EnPAx for co-organising the event and questionnaire, and to all who responded and attended for their valuable input.