Deliberate attacks on industrial infrastructure are common to many conflicts and often justified on the basis of military necessity.

The deliberate or inadvertent damage or destruction of industrial facilities during conflict has the potential to cause severe environmental damage and create acute and long-term risks to civilians. Can such attacks ever be justified, particularly when the consequences of attacks may be difficult to anticipate with any degree of certainty?

Industrialisation and insecurity

Global population growth, and with it increasing levels of industrialisation, is increasing the likelihood that in any given conflict, fighting may occur in areas containing industrial infrastructure. Consequently, the likelihood of damage to such sites is increasing. Industrial sites whose products are utilised by militaries, such as petrochemical plants or processors, may be viewed as bona fide targets under international law, yet over the last two decades there are numerous examples where the direct military benefits from deliberate attacks have at times been difficult to determine.

While international humanitarian law seeks to provide some measure of prohibition on attacks against infrastructure containing ‘dangerous forces’, such as nuclear power plants or dams, is this broad enough? Should facilities manufacturing or using chemicals also be viewed as containing dangerous forces? The evidence from peacetime incidents in Seveso, Bhopal, Pasadena, Enschede and Baia Mara could all be viewed as evidence that they should.

Threat perception

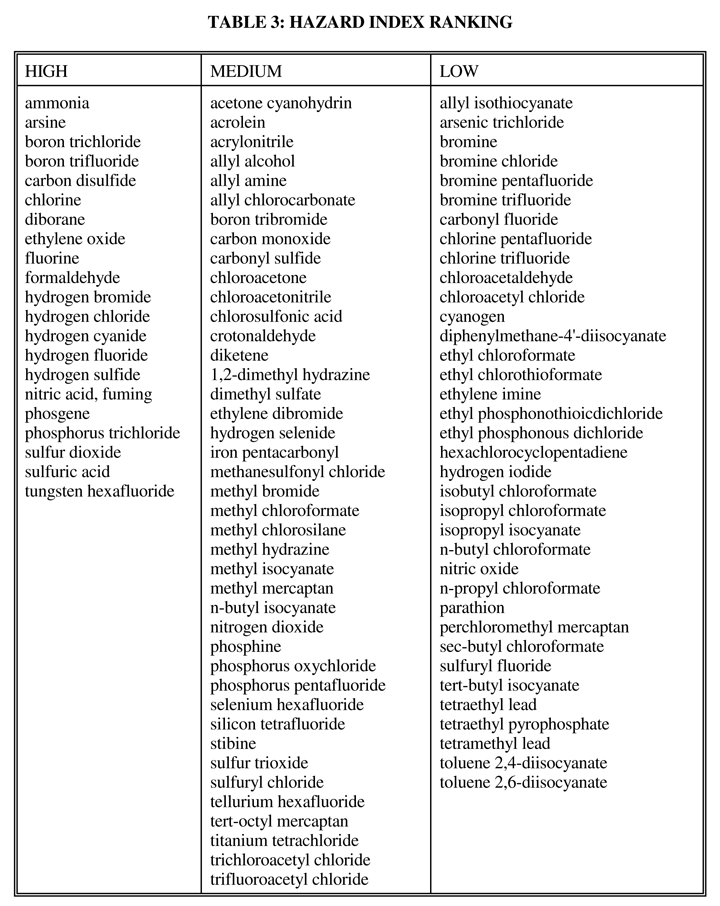

The threat posed by the inadvertent or deliberate release of Toxic Industrial Materials (TIMs or Toxic Industrial Compounds TICs) has been recognised by the military for many years. Their focus has primarily been on the risks to troops and mission success from what could potentially constitute an environment analogous to NBC warfare. In 1996, a US-UK-Canadian (CANUKUS) task group (IT-25) published the results of a study on TIMs. It was convened after the use of chlorine was threatened in the Bosnian conflict and sought to identify those substances that, by virtue of their widespread use, toxicity and other physical characteristics, were deemed particularly hazardous or problematic to military activities in a conflict or post-conflict environment.

CANUKUS International Task Force 25 hazard ranking for common toxic industrial chemicals.

The task group found that:

“There is a threat from toxic industrial chemicals, but the hazard is manageable provided commanders are educated about and informed as to the extent and nature of the threat. The potential impact of deliberate or accidental releases of industrial chemicals on CANUKUS forces may be lessened, but to do so it is imperative that all elements of training, preparation, prediction, detection, protection, and countermeasures, be considered before deployment to an area.”

Needless to say, civilian populations living in proximity to hazardous sites during conflicts may not have the benefit of preparation, prediction, detection, protection or countermeasures.

It’s not just a case of threats from accidental or collateral damage to sites. For some strategists, fear of the threat posed by TICs has been intense, likened by some in the post-9/11 context as a poor terrorists’ WMD. One example that is often cited for the deliberate weaponisation of industrial sites stems from the Croatian War of Independence in the early 1990s. The incidents saw repeated deliberate attacks by Serb forces on a large petrochemical facility adjacent to the town of Kutina (pop. 40,000) between 1991 and 1995, which are thought to have been intended to cause civilian deaths. In one of a number of other incidents an oil refinery near Sisak was deliberately attacked with artillery 27 times between September 1991 and June 1992. This led to repeated fires and damage to the complex and is thought to have caused the release of around 90,000 cubic metres of crude oil and other chemicals into two nearby rivers, together with considerable atmospheric pollution.

Further work on mitigating the risks from TIMs followed the 1996 task force recommendations, with guidelines developed by the US and others, again to protect military personnel. These included minimum safe distances from installations and a range of other protective procedures, the risks were framed by the US thus:

“Release of TIC is most dangerous at night because typical nighttime weather conditions produce high concentrations that remain close to the ground for extended distances. TIM can have other significant hazards. TIC are often corrosive and can damage eyes, skin, respiratory tract, and equipment. Many TIM are flammable, explosive, or react violently with air or water. TIM can have both short- and long-term health effects, ranging from short-term transient effects to long-term disability to rapid death. Military protection, detection, and medical countermeasures are not specifically designed for the hazards from TIM. Often there are no specific antidotes for TIM.”

Bad bombs, good bombs and looters

Evidently military understanding and awareness of the risks that uncontrolled releases of industrial chemicals can pose to both human health and the environment have developed considerably over the last few decades. At times condemnation of deliberate attacks has been vocal, although controversy has not always translated into changes in practice.

The 1991 Gulf War saw some of the most wanton acts of pollution in history after retreating Iraqi forces detonated Kuwaiti oil wells and opened pipelines, creating vast slicks in the Persian Gulf. The fires and spills rightly generated global condemnation, and as a result the environmental conduct of Iraq framed the debate on protection for the environment during conflict for years afterwards.

Speaking at a legal symposium hosted by the US Naval War College in 1996, Rear Admiral Biff LeGrand, the then Deputy Judge Advocate General of the US Navy argued that:

“After the Gulf War, the Department of Defense issued a report detailing the extent to which law of armed conflict concerns permeated strategic decisions at every stage. For instance, during the conflict, bombing targets were carefully selected to avoid civilian population centers, cultural and religious structures and environmentally sensitive areas, even when it became apparent that Iraq was conducting military activities from such sites. In the view of those who believe the current law of armed conflict protects the environment effectively, the Allied restraint shown in the Gulf War is supporting evidence that militarily powerful nations, such as the United States, are able to accept, implement and effectively enforce limitations on the conduct of armed conflict.”

Yet just three years later, and as part of NATO operations against Yugoslavia, the US would get a taste of the opprobrium levelled on Iraq’s conduct in 1991. The decision by NATO to try and topple Slobodan Milosovic by waging war against Serbia’s infrastructure caused huge releases of pollutants. The military necessity justification for their actions rapidly wore thin as footage of oil fires, blackened metal and broken bridges spread around the world.

As Prof Joel Hayward, the former director of the Royal Air Force’s thinktank has observed:

“NATO failed to explain convincingly why its remarkably precise and thus potentially highly discriminate air force needed to destroy the storage tanks, thus burning or spilling staggering quantities of liquid hydrocarbons and chemicals, rather than less harmfully targeting the adjacent but separate refinery installations, or, far better still, precisely hitting the more discrete river port, road, and rail nodes to stop loading, transportation, and distribution of the oil and chemicals.”

By the 2003 Iraq War, different threats to civilian and environmental health from industrial materials had emerged that were linked to insecurity and institutional breakdown. Overall, Iraq’s already faltering industrial infrastructure largely escaped the gratuitous bombing seen in Serbia in 1999. Those sites that were hit by Coalition airstrikes tended to have a relatively clear dual civilian/military use, although on a number of occasions heavy ground fighting took place in and around industrial areas causing damage to sites and the release of pollutants.

More problematic was the outcome of the US’s decision to deploy a comparatively small ground force in the conflict. This led to the failure of the Coalition to secure territory effectively and ensure the security of industrial sites. The collapse of the regime triggered widespread looting, whose damage to industrial sites, according to UNEP “cannot be underestimated”. UNEP argued that:

“…the environmental damage caused by post-conflict looting throughout Iraq has apparently exceeded the damage caused by direct conflict in 2003. The looting of industrial sites presents a major risk to human health in itself, and [as of 2005] this risk remains uncontrolled.”

Common sense versus collateral damage estimation

While views on the acceptability of attacks on industry currently vary from conflict to conflict and on who is involved, the dictates of common sense suggests that they are best avoided. One obvious issue is the unpredictability of the outcome of attacks and the potential for harm to the environment and civilians. Recently released US documents on methodologies for estimating collateral damage from planned air or artillery strikes shed some light on the calculations used to identify the risks and acceptability of attacks. However it remains more art than science and only applies to those attacks that are pre-planned.

Prior knowledge of the contents and design of industrial sites is critical in estimating risk, necessitating a heavy reliance on intelligence, which may not always be as robust as required. One notorious example of poor intelligence dates back to the 1991 Gulf War where pharmaceutical and baby formula factories were destroyed in the mistaken belief that they were part of Iraq’s biological weapon facilities.

Under the methodology released in 2012, targets assessed by the US to have the potential to generate chemical or environmental risks during the planning process may trigger additional analysis via the political Sensitive Target Approval and Review (STAR) process or the scientific Chemical Hazard Area Modeling Program (CHAMP). While the STAR procedure has remained classified, the mathematical models used for CHAMP are available.

CHAMP’s primary function is to seek to model possible atmospheric plumes and the health risks posed by substances over a given area. However, the exposure standards used appear to be military specific, which tend to be higher than those for civilians, and significantly higher than those for the most vulnerable sections of the population. Similar models are used within the civil sphere for predicting and responding to large chemical incidents, such as that developed by the Global Health Security Initiative following 9/11.

Ultimately the decision to attack, and how to attack, will rest with the judgement of the commander and will be taken in accordance with the rules of engagement for that particular operation. In spite of the models, the weight of uncertainty inherent in predicting the immediate and long-term environmental and civilian harm from such attacks should be foremost in calculations over whether to proceed with an attack. But is it possible to effectively integrate fuzzy concepts like uncertainty into rigid decision-making structures of this sort?

Take precautions or change behaviour?

While the US and other advanced militaries may increasingly be taking such methodologies into account, this is not universal. Furthermore, even where collateral impacts are considered, all too often perceived military necessity still trumps environmental concerns, as has been demonstrated by the numerous Coalition airstrikes against oil facilities in Syria. Similarly the conflicts in Lebanon, Gaza, Libya and Ukraine have all shown that other nations and non-state actors still view attacks on industry as perfectly legitimate.

The extent to which these environmentally risky behaviours can be modified by military guidelines alone is questionable. Improvements to industrial safety in the civil sphere have tended to require both visibility and some form of accountability. It is perhaps ironic that industrial attacks have caused some the most shockingly photogenic forms of environmental damage from past conflicts and yet even these often fade from the media and political agenda in the face of competing narratives. Thought should be given as to how these forms of damage can be put on the agenda and kept on it through more responsive conflict monitoring systems.

While post-conflict environmental assistance for remediation remains ad hoc and dependent on the largesse of one or two sympathetic states, it is difficult to envisage a time where belligerents are forced to acknowledge some responsibility for the environmental costs of attacks. A sense of financial accountability for damage could perhaps prove a valuable component in the calculations of commanders and those drafting rules of engagement.

The other question that remains absent is that of civilian harm from the toxic remnants generated by attacks or post-conflict insecurity. Until such time that robust and consistent efforts are made to determine whether civilians have been, or may continue to be, exposed to pollutants from damage to industrial sites, it is unclear how society or the military can properly judge the acceptability of these targeting decisions.

Although it is perhaps too much to hope that the development of a norm that helps to de-legitimise attacks on industrial sites could also help deter those intent on using them as a weapon of war, it would at least ensure some consistency in their condemnation.

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project