Tracking fires can help locate informal dumpsites that pose health and environmental risks to communities.

The war in Yemen has profoundly affected solid waste management, increasing open dumping and with it risks to the environment and public health. In this post, Hanna Schulten explores how satellites can identify dumpsites and so help inform remedial measures and waste management policies.

Health and environmental hazards from solid waste in Yemen

While the intensity of Yemen’s near decade-long conflict has subsided, the country remains far from peace. At the conflict’s outset, Yemen already placed 160 out of 177 on the Human Development Index, solidifying its status as one of the world’s most impoverished nations. During the conflict, many waste management challenges arose, leading to the proliferation of informal dumpsites and compounding environmental and health hazards. The war also strained economic resources, disrupted waste infrastructure, and diverted attention away from waste management.

The strain on Yemen’s already inadequate waste management infrastructure manifested in three main ways. Firstly, through service impacts, which have included damage to formal waste facilities, such as the bombing of the Sana’a waste processing facility in 2015, and a drastic reduction in urban waste collection rates due to soaring fuel prices. Secondly, through waste composition – pre-existing challenges around the segregation of hazardous materials were exacerbated by building debris volumes, medical waste, and even explosive remnants of war. And thirdly through disruptions to systems of waste governance, from the local to national levels.

Informal waste sites filled with unsorted hazardous waste pose significant environmental pollution risks through the air, water and through soils. Air pollution commonly occurs during waste fires, releasing gases like sulphur dioxide, as well as carcinogens and heavy metals into the environment. Through water, leachates from landfills can contaminate agricultural and drinking water resources, upon which vulnerable populations often rely. The 2016 cholera outbreak in Yemen, which resulted in 3,000 deaths, was potentially linked to untreated medical waste polluting waterways. These interconnected hazards highlight the importance of sound waste management practices to safeguard public health and the environment in conflict-affected areas.

Finding informal dumpsites and landfills

Yemen’s problems are not unique. However, the proliferation of informal dumping in areas affected by conflict, or the expansion of hazardous landfills, is not always straightforward to document remotely. Satellite remote sensing has underutilised potential for identifying and monitoring such sites.

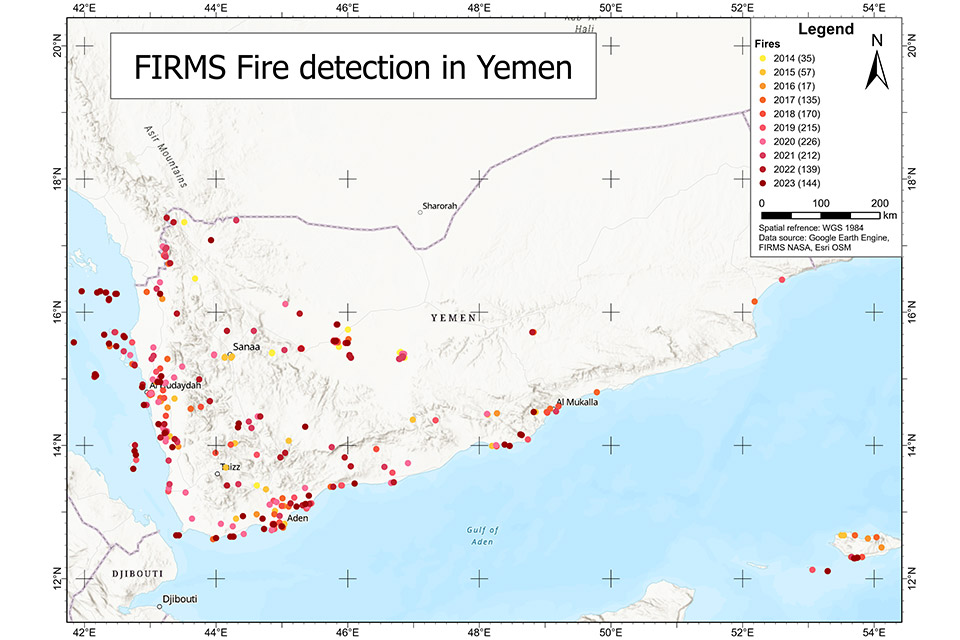

Open dumping and poor dumpsite management are often associated with waste fires. This means that monitoring for fires using NASA’s Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) can spot dumpsites. When I used this method during my research, it revealed 1,350 fires between October 2014 and October 2023. Figure 1 shows their spatial distribution, and concentration in urbanised areas along Yemen’s populous western and southern coasts. The locations aligned with densely populated regions and included residential areas lacking proper waste management services. Notably, the capital Sana’a experienced relatively few fire incidents.

The majority of fires occurred in 2019 and 2021, with 215 and 226 incidents respectively, whereas the period 2014-16 saw fewer fires, with only 17 recorded in 2016. Although fire frequencies diminished in 2022 and 2023, both years still reported more than 100 fires annually.

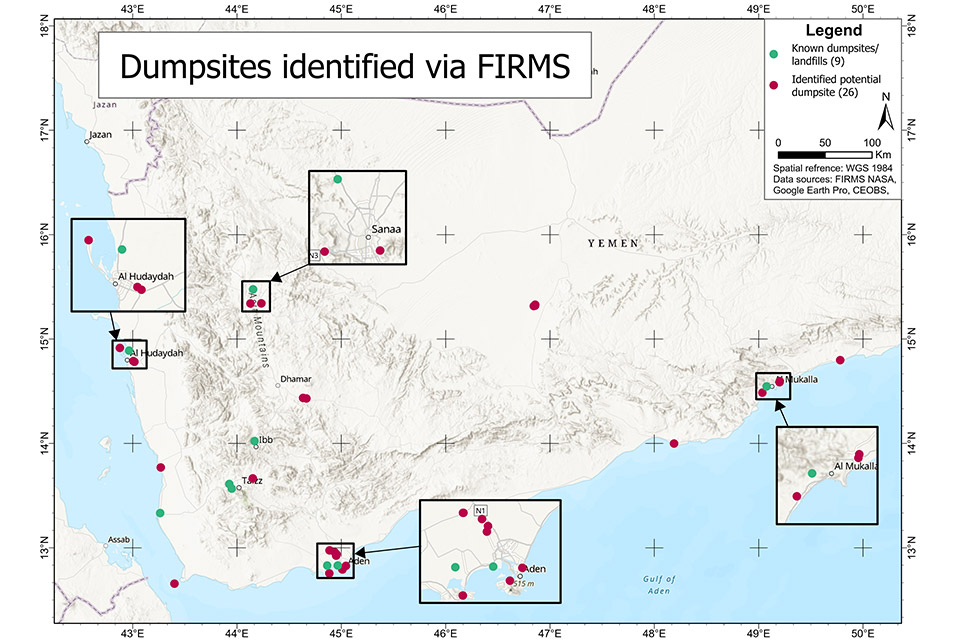

Confirmation with very high-resolution satellite imagery

After identifying potential dumpsites, I confirmed their location using imagery in Google Earth, making particular use of its back-in-time feature. In this way I was able to identify 26 new waste sites, supplementing nine sites identified in earlier research. As anticipated, these tended to be close to urban areas and mostly around larger cities. Both Sana’a and Al-Hodeidah in the north had two new dumpsites but most had emerged around Aden; the city had experienced a significant decline in waste collection rates, potentially explaining the proliferation of informal dumpsites. In contrast, Sana’a had seen a lower decrease in waste collection rates.

Interestingly, the emergence of new informal dumpsites did not seem to be influenced by whether an area was controlled by the Houthis, the Southern Transitional Council (STC) or the government. Nor did proximity to official landfills appear to deter the formation of informal landfills, as evidenced by the cases of Aden and Al-Mukalla in the south.

Another approach to identifying informal landfills using remote sensing data involves detecting spikes in land-surface temperature (LST). This method not only identifies fires but also potential subsurface fires, which are typically harder to detect. Subsurface fires can manifest as thermal hotspots on remote sensing imagery.

Satellites like Landsat 8 provide suitable LST data but although its high-resolution data is accessible it ultimately proved impractical for landfill detection because of the data’s timeframe. Dumpsite fires typically occur and dissipate within days, and so were not captured by Landsat.

Yemen’s deteriorating waste management system poses significant harm to both its environment and its people, and as part of my research I examined the risks posed by two sites.

The environmental risks of Yemen’s informal landfills

The ecological and climate impacts of informal landfills in Yemen, particularly in Ras Isa and Sana’a, highlight critical concerns regarding the country’s waste management system. In Ras Isa, improper dumping practices near the coastline contribute significantly to marine and groundwater pollution. Leachate from accumulating waste seeps into the soil and reaches coastal waters, disrupting marine ecosystems and endangering species. Plastics from these landfills also break down into microplastics, which are ingested by marine organisms and bioaccumulate through the food chain. The threat of marine pollution in Ras Isa gained international attention due to the SAFER oil tanker crisis. The single-hulled tanker, holding 1.14 million barrels of oil, posed a severe risk until the UN intervened in 2023, successfully averting a potential oil spill that would have devastated marine life.

In Sana’a, the landfill’s contribution to climate change is profound, primarily due to methane emissions. As organic waste decomposes anaerobically, methane — a potent greenhouse gas — is released, exacerbating global warming and local air pollution. Mitigating these impacts necessitates comprehensive strategies, including landfill gas capture and utilisation systems to convert methane into energy and waste diversion practices like composting and recycling to reduce organic waste. However, the ongoing conflict in Yemen often sidelines environmental protection efforts, making it challenging to address these critical issues effectively.

Constraints on the remote identification of waste sites

The identification of waste site locations is hindered by the resolution of publicly available satellite imagery. Public datasets on informal waste sites in Yemen are broadly absent and challenges remain around ground-truthing remote data, suggesting the need for collaboration with Yemeni stakeholders on the ground. Critically, quantifying the actual environmental risk to people and ecosystems if impossible using these methods alone.

But identifying sites is just one small part of the solution. Addressing solid waste management in Yemen requires comprehensive and context-specific strategies. Efforts to improve waste management infrastructure, promote sustainable practices, and mitigate existing and emerging environmental risks are important to safeguard public and ecosystem health but will remain complex for as long as Yemen’s political situation does.

Hanna Schulten studied Yemen’s landfills as part of her Bachelors thesis in Applied Geography at RWTH Aachen University in Germany. Her project was inspired by CEOBS’ earlier work on this issue.