Militarising environmental problems means losing opportunities for cooperation.

There are growing calls for the UN Security Council to authorise a military-backed response to the crisis over the SAFER oil tanker off the coast of Yemen, in order to prevent an environmental and humanitarian disaster. In this blog, Doug Weir argues that not only is this unrealistic, it would also have long-term consequences for how the international community addresses the environment, peace and security.

The SAFER crisis enters uncharted waters

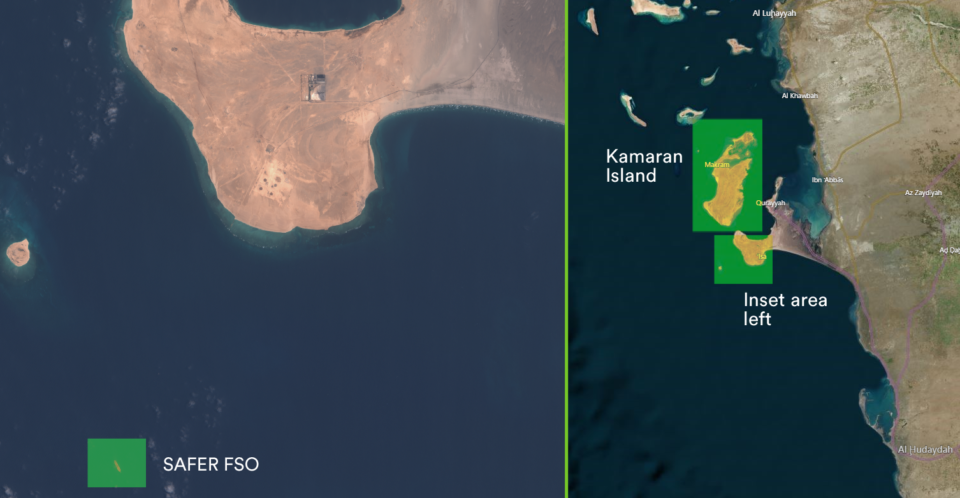

Since we raised the alarm in early 2018, the FSO SAFER, a rusting, single-hulled oil tanker containing 1.14 million barrels of oil has received international attention. And since April 2019, the threat the SAFER poses has been raised every month in the UN Security Council. Permanently moored off the Yemeni port of Ras Isa, a catastrophic fire or spill from the dilapidated vessel would cause an environmental and humanitarian disaster for Yemen, and the wider Red Sea. While the options to reduce the risks it poses would be comparatively straightforward in peacetime, the vessel is moored off an area of Yemen controlled by the Houthis, and the Houthis have shown minimal interest in addressing the problem.

With fears of a spill increasing, and with frustration at Houthi intransigence growing, there have now been calls for a military solution to be mandated by the UN Security Council. This blog examines how we reached this point, the risks that a military solution might create, and the wider implications for how the UN Security Council addresses the environment, peace and security if such an option is pursued.

How did we get here?

The inclusion of the SAFER in Mark Lowcock’s monthly UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) briefings to the UN Security Council in April 2019 led to an uptick in exchanges and media reports about the fate of the SAFER, its risks and the Houthis shifting positions on a salvage operation. Media attention escalated in July 2019, and major NGOs and states urged action, leading to the Security Council becoming increasingly seized of the matter. By February 2020, the SAFER had found its way into its resolution on Yemen.

Perversely, the increasing international attention, while absolutely vital, increased the political value of the SAFER crisis to the Houthis. Where once the focus had primarily been on the economic value of the vessel’s contents, and its function as an export terminal, the SAFER’s fate had now become one of comparatively few bargaining chips available to the internationally isolated Houthis. Critically, the Houthis began arguing that the SAFER could not be dealt with in isolation, and must instead be part of a wider agreement.

By June 2020, reports surfaced of a leak in the SAFER’s engine room, and the efforts by the crew to repair it. Continued media attention, and the advocacy of the internationally recognised government of Yemen and regional states, led to the decision to hold a virtual Security Council session dedicated to the SAFER. The July 15 meeting was preceded by a UN leak that the Houthis had agreed to a UN-led technical inspection, as a first step towards a solution to the crisis.

The deal on the table had three components: assessment and necessary repairs; basic maintenance to facilitate oil extraction; and finally, the disposal of the tanker. All proceeds from the sale of the oil, which had plunged in value during the pandemic, was to contribute towards Yemeni civil servant salaries.

There was considerable scepticism from the parties involved, with Mark Lowcock confirming that the previous week: “Ansar Allah [Houthi] officials confirmed to the United Nations in writing that they are ready to authorize the United Nations mission to the FSO SAFER. They have also communicated their intention to issue entry permits for mission personnel. I welcome that announcement. We have, of course, been here before. In August 2019, we received similar assurances and, on that basis, deployed the United Nations team and equipment to Djibouti at significant expense. The Ansar Allah authorities cancelled that mission the night before departure.”

By September, detailed talks were still ongoing between OCHA and the Houthis on the process, with the proposal subject to repeated revisions. News that another reported leak from the SAFER had been confirmed was a reminder of the parlous state of the vessel. As October drew to a close there were signs that agreement had been reached, and in early November a technical document was published by UNOPS, which underlined the technical challenge the operation would involve. In late December the UN published a Q&A on the mission, whose scope was now:

- To assess the condition of the SAFER oil tanker through analysis of its systems and structure;

- To conduct urgent possible initial maintenance that might reduce the risk of an oil leak until a permanent solution is applied;

- To formulate evidence-based options on what solutions are possible to permanently remove the threat of an oil spill.

By early February 2021 the plans were on hold after the Houthis had failed to provide written security assurances to the UN. By this point the UN had reportedly spent $3.5 million preparing for the mission. The internationally recognised government of Yemen wrote to the Security Council urging it: “… to take binding deterrent measures against the Houthis to ensure the urgent unloading of oil and the disposal of the tanker, before the world wakes up to one of the biggest environmental and humanitarian disasters ever for both the region and the world.”

A proposal advanced by IR Consilium provided detail on what these stricter measures could involve: ‘The mission would include engineers, backed by armed forces, demining water near the floating storage and offloading platform, and spending one month carefully draining the tanks before the tanker was scrapped.’ Shortly after, the Security Council strengthened its language on the SAFER in a new resolution on Yemen. While the text stressed the responsibility of the Houthis for the situation, and underscored the need for them to facilitate access, it did not include the hardline approach some were advocating for.

The Houthis responded by blaming the UN for the delays, citing changes to the personnel requiring visas. With its Supervisory Committee for the Implementation of the Urgent Maintenance Agreement and the Comprehensive Evaluation of the Floating Safer Reservoir announcing its: “…full commitment to implementing the agreement and its keenness of concern for the safety of the marine environment in the Red Sea.”

By March, Lowcock was criticising the Houthis for a lack of flexibility, and saying that the UN continued to discuss logistical issues. Meanwhile on Twitter, Mohammad al-Houthi was publicly rejecting the proposal from the UN that a six nautical mile exclusion zone be placed around the SAFER during the assessment, saying that the condition was outside the initial agreement.

Months on from the July 2020 Security Council meeting, and it feels that little progress has been made.

Is there a military solution to the SAFER crisis?

Evidently the hard line being promoted by the internationally recognised government of Yemen is not just a vehicle for pressuring the Houthis. As serious proposals are now being made for a military-backed intervention, it’s vital that these are properly scrutinised. Before doing so, it’s necessary to be clear on the two salvage approaches on the table. The UN approach is for a technical assessment and urgent repairs, and then to identify proposals for next steps towards salvage. The primary aim being to stabilise the vessel.

Those favouring a more urgent response argue that the vessel cannot be meaningfully made safe, and that it should be assessed and the oil unloaded onto a seaworthy tanker that can be moored nearby. This combined operation would leave a vessel containing the oil in the Houthis’ hands, although not a functioning oil export terminal with the potential to sell oil from the Marib field: although the extent to which the dilapidated SAFER would be able to fulfil this function following the conflict is highly doubtful.

The UN approach requires and has sought cooperation with the Houthis, whereas the urgent approach requires their “acquiescence” – it also assumes that the Houthis see a greater financial value in the SAFER’s contents, than they do in it as a bargaining chip in future peace talks. Those advocating for urgency suggest that the UN approach has failed, that the unloading plan will inevitably require military minesweepers to secure the waters around the vessel, and for foreign militaries to secure the vessel, or to provide security in the event that the Houthis changed their minds, or if Houthi elements take matters into their own hands during the estimated month-long process. It is suggested that: “The only way for that to happen at this point is via a UN Security Council Resolution under Chapter VII.”

Needless to say, the proposal raises a number of issues. Foremost among which is whether a military operation would increase the risk of an incident leading to a spill from the vessel, which is moored just 7km offshore. Would security need to be provided both at sea and onshore during what would inevitably be a very, long month, and how could the operation avoid provoking an escalation?

How would an authorisation work?

The Council’s current resolution already determines that the situation in Yemen continues to constitute a threat to international peace and security – the first bar needed for implementing Chapter VII (under art 39, UN Charter). And the text of the resolution already contains measures under Chapter VII, such as economic sanctions and efforts to reduce flows of weapons from Yemen. To authorise a use of force under article 42, the text would need to include language permitting states to take “all necessary measures/means”, in this case to address the humanitarian and environmental threat posed by the SAFER.

Chapter VII, Art. 42: Should the Security Council consider that measures provided for in Article 41 would be inadequate or have proved to be inadequate, it may take such action by air, sea, or land forces as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security. Such action may include demonstrations, blockade, and other operations by air, sea, or land forces of Members of the United Nations.

The use of force should be viewed as a last resort, after all other measures have been exhausted – although this is not always the case in practice. Some would doubtless argue that in this instance, the current cooperative UN approach has indeed failed and that military action is justified. The resolution would need the votes of nine of the Council’s members, including all five permanent members, and could contain a timebound summary of what steps would be taken, and by whom. Those advocating for this approach have proposed that a comprehensive spill response plan be developed and in place prior to proceeding.

Why an authorisation is unlikely to happen

The UN Security Council has never approved the use of force to directly address an environmental threat, and the chances of all of its permanent members doing so now are remote. While Council resolutions have addressed environmental issues indirectly, such as the role of natural resources in fuelling conflict in the DRC, or the role of environmental degradation in the Lake Chad crisis, this would set an entirely new precedent.

Following the Cold War, the Council has expanded the scope of what constitute threats to international peace and security on a number of occasions, for example on international terrorism. These decisions are entirely political, and undertaken at the discretion of Council members. However, this expansion of the Council’s (international executive) authority has come without an expansion of democracy, and meaningful efforts towards reform, including ensuring its accountability.

Since 2011, and the mission creep following the resolution authorising the use of force to protect civilians in Libya, Russia and China have been very reluctant to grant authorisations. Even in the case of the fight against Da’esh in Syria, the Council resorted to what has been generously described as “constructive ambiguity” in formulating the text of the relevant resolution. In light of this, it seems unlikely that Russia in particular would authorise force to address an environmental emergency, particularly given its longstanding view that environmental issues have no place in the Security Council.

Moreover, the geopolitical context beyond the Council does not appear conducive to an authorisation. For example when asked in a UN press briefing in February about the suggestion that the Council could authorise the use of force in the case of the SAFER, Stéphane Dujarric, Spokesman for the Secretary-General said: “I can’t tell you that that’s a discussion that I’m aware that has taken place, and I think we can all imagine… and I’ll just leave it at that.”

Relations between Russia and the new US administration are strained, while US support for Saudi Arabia’s war is weakening. The last two weeks have seen peace deals proposed by the US and by Saudi Arabia itself. The question of whether Russia and Iran could have persuaded the Houthis to cooperate with the UN prior to this point if they had wished to remains an open one. It has been Western states that have been championing the case of the SAFER, many of whom, like the UK, are not neutral actors in the conflict. This has inevitably contributed to the politicisation of the issue, making the steps now being proposed all the more difficult.

Environmental cooperation or confrontation?

Questions have long been asked over whether and how the Security Council should expand its environmental mandate. The question lives on through the ongoing debate over climate security, which now sees majority support from member states but consensus remains elusive. Earlier scholarly work did not discount the idea that the Council could respond to environmental emergencies where they have clear humanitarian consequences, or where they have become bound up in a dispute, but the question is one of how.

Issues like the SAFER are primarily technical problems that require cooperation. As soon as they are securitised or militarised in contested settings, opportunities to cooperate are diminished. Similarly, a narrow focus only on the threat itself ignores the wider context of the conflict, and can obscure the motivations of opposing parties. In the case of the SAFER, the Houthis have been clear that they see its resolution as part of a wider peace agreement – that is its value – and they seem content to accept the risk of – and responsibility for – an environmental catastrophe in pursuit of their goals.

More broadly, a resolution authorising the use of even limited force to address an environmental threat raises a whole suite of ethical and practical considerations. What would the contours or limits of these environmental interventions be, and under which circumstances would they be authorised? A dilapidated tanker? A failure to protect a rainforest? A breach of Greenhouse Gas emissions targets? There are important and sober discussions to be had here, particularly where an initiative like that proposed for the SAFER could risk efforts to deepen Security Council engagement on climate change.

Perhaps most fundamentally, militarised responses to environmental threats can rob them of their ability to be a vehicle for cooperation, for confidence building and for peace. Environmental threats rarely recognise borders and tackling them typically requires the input of more than one party. And, while they are clearly not immune to politicisation – as the case of the SAFER attests – this is not inevitable. While the Security Council needs a mandate on the environment, peace and security, it must be one that contributes to those objectives, rather than one that undermines them.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director, Stavros Pantazopoulos contributed to this blog.