Environmental Mechanics: Re-imagining post-conflict environmental assistance

Download as PDF · Published: November 6, 2015 · Categories: Publications, Law and Policy · Author: Doug Weir

Introduction

Regardless of cause, pollution and environmental disruption from conflict can lead to the loss of access to resources upon which the civilian population depends, such as water and agricultural land, and acute and long-term threats to public health, well-being and livelihoods. Wartime environmental damage has a humanitarian impact and environmental protection and the protection of civilians should no longer be viewed as separate and distinct policy objectives.

At present, the parties to armed conflicts face few environmental constraints over how they conduct hostilities. The result is that there is a significant imbalance between perceived military necessity and the requirement to protect the environment. This is true of current methods of warfare and, without some progress in the field of environmental protection, will doubtless remain true in future. At times, the results of this imbalance may be highly visible, for example deliberate attacks on industrial facilities, but in other cases damage may be subtle and cumulative.

Legal protection for the environment in conflict is widely viewed as inadequate. Since 2009, a decades-long debate over how it could be strengthened has been renewed following a fresh analysis of the legal gaps by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). To date this has mainly focused on the applicability and utility of existing legal regimes, such as International Humanitarian Law, International Environmental Law and Human Rights Law. Yet how the international community currently monitors wartime damage to the environment, assesses its impact and ensures assistance and remediation, can also provide inspiration over how protection could be strengthened.

While this renewed debate has been a welcome development, it has also carried with it risks. The first has related to scope. Conflict and the environment is an enormously broad topic. This has made it challenging to focus in on where there is potential for progress, certainly within the context of short expert meetings or seminars. With this in mind, we have chosen to focus our work on the humanitarian consequences of environmental damage, which to date has focused on conflict pollution and environmental degradation. Nevertheless, many of the observations and suggestions in this report will be relevant to other forms of wartime damage.

The extent to which such an anthropocentric approach could also ensure protection of the natural environment remains to be tested. However, the history of both environmental and disarmament initiatives suggests that clearly defining the humanitarian imperative for environmental protection could provide a more manageable framework for meaningful debate and policy development.

The second risk with the existing discourse is that over-analysis of the applicability of particular strands of law, or particular treaty regimes, can create a conceptual cage. This report has sought to step out of this cage. In doing so, it considers the principles established by these regimes without dwelling on whether or how these specific regimes could be used to apply them to wartime environmental damage. Instead we consider how these principles could be used to inform a new system of post-conflict assistance. To complement this approach, we have also considered the mechanisms and structures utilised by existing environmental and disarmament agreements and translated them to the context of a new hypothetical system of post-conflict environmental and humanitarian protection.

The overarching purpose of the report is to encourage more focused debate on what we consider to be key considerations for any future attempt not only to address the legacy of wartime environmental damage but also to establish and develop new behavioural norms to minimise harm. Some of the elements in this report have been suggested by others. Some build on existing practice. All have been influenced by our research and observations during the three years of the Toxic Remnants of War Project’s existence.

Where we have borrowed from others, our aim has been to try and add additional analysis to these pre-existing proposals in order to develop ideas further. Our objective throughout has been to encourage debate by being creative. This is not a list of demands for any future initiative. Instead the report is a vehicle through which to highlight topics that we believe should be addressed more fully by a range of stakeholders. We are deeply indebted to everyone with whom we have discussed these observations and ideas with during the last few years.

Recommendations

General recommendations

Five recommendations for states and civil society that wish to support the new discourse on strengthening protection for the environment in relation to armed conflicts.

1. States should review the effectiveness of the UN system’s ability to address the environmental dimensions of peace and security.

This report has highlighted a number of shortcomings in how the international community collectively responds to environmental damage in relation to armed conflicts. Significant improvements could be made at a number of levels and across the UN system, for example in relation to more effectively integrating environmental considerations in the mandates of peacekeeping operations. Consideration is needed over whether UNEP has sufficient resources and mandate to assess and address the environmental and humanitarian impact of the widest possible range of conflicts. Where gaps exist, civil society should be encouraged to support and augment UNEP and other UN agencies’ efforts in this regard. In order to ensure greater visibility and prioritisation of the environment than exists at present, a forum may need to be identified where the environmental dimensions of peace and security can be properly scrutinised by states, international organisations, civil society and experts.

2. States should promote progressive interpretations of the applicability of environmental and human rights law.

This study, and the decades of legal discussions that preceded it, has shown how principles, practice and precedents from international environmental law, human rights law and disarmament law could help inform new approaches on conflict and the environment. This progressive approach has also been in evidence in the interventions of some states during UN Sixth Committee debates on the International Law Commission’s ongoing study on protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts. States that support progress on conflict and the environment should recognise and endorse the utility and applicability of the principles within these regimes during statements in relevant fora.

3. Support focused work to define the humanitarian imperative for strengthening environmental protection in relation to armed conflicts.

There is already a broad understanding that environmental damage, be it pollution or the degradation of resources, carries with a cost to civilian health and livelihoods, but it is debatable whether this is being properly communicated at present. Improving how we define and document harm, and how we communicate it, would help build a clearer understanding of the humanitarian consequences of wartime environmental damage. This is an area that is severely under-addressed at present. Doing so is a pre-requisite for any meaningful political effort to strengthen legal protection. Donors, international organisations, academia and civil society all have an important and complementary role to play in defining what we mean by harm, and in documenting it, and should deepen their collaboration to achieve this objective.

4. States should ensure that environmental practitioners, affected states, civil society organisations and communities can fully engage with the new discourse on strengthening protection of the environment in relation to armed conflict.

The last few decades of debate on strengthening protection of the environment in relation to armed conflict have primarily focused on legal analysis, or have been weighted towards military, rather than humanitarian considerations. In order to move beyond this, it will be necessary for states and international organisations to facilitate the inclusion of a wider range of perspectives. This should not only include the practitioners of international organisations who work on these issues day to day, but also expertise from states affected by wartime environmental damage, civil society organisations and representatives from affected communities. Without the inclusion of these perspectives, the topic risks remaining of academic interest only, making further progress difficult.

5. The ICRC should continue and intensify its engagement on conflict and the environment.

The 2011 Pledge by the Nordic governments and Red Cross societies to pursue research and host expert meetings on conflict and the environment during the last five years has made a useful contribution to the developing debate. A second Pledge to continue this work would be a welcome outcome of the 2015 ICRC conference and efforts should be made to engage states and national societies from beyond the Nordic group to ensure a more inclusive and globally representative approach. National societies should consider the merits of establishing a focal point for the topic within the movement to help create and sustain relevant expertise. Finally, the movement as a whole should help contribute to efforts to document and define the humanitarian consequences of wartime environmental damage.

Thematic talking points

These six thematic questions, which form the basis of the six sections of this report, are proposed as a framework for further focused debate over how the current gaps in post-conflict environmental response might be addressed.

International assistance and co-operation

What would be an appropriate model for establishing the principle of international assistance and cooperation with respect to managing wartime environmental damage?

Financing assistance

What is the best way of ensuring that urgent funding and technical assistance is always available to states affected by wartime environmental damage?

Monitoring harm and access to information

How can we increase the amount of information that is gathered on the human and environmental impact of wartime damage?

Community assistance

How can we ensure that communities and individuals affected by wartime environmental damage or degradation are identified and assisted?

Remediation and restoration

To what extent should states affected by wartime environmental damage be obligated to ensure that the rights of their citizens are protected?

Review body

What is the most effective way to establish and promote new behavioural norms, guidelines and best practice that could minimise environmental damage in both international and non-international armed conflicts?

Context

Damage to the natural environment has long been a hallmark of conflict but changes to the nature of warfare, both in terms of technological developments in how hostilities are conducted and the locations in which wars are fought, are increasing the risk of serious long-term environmental damage, and with it threats to the civilian population. There is a consensus view among legal scholars and, increasingly, international organisations and some states, that International Humanitarian Law’s (IHL) current provisions for the protection of the environment during conflict are unfit for purpose.1 Furthermore, the absence of a common international standard for minimising harm and dealing with the environmental legacy of armed conflict is creating persistent environmental problems, and with them, long-term risks to the health and livelihoods of civilians.

The breadth and complexity of what is commonly regarded as “conflict and the environment” has often hindered historical efforts to develop new standards intended to minimise and restore damage and protect civilians. Although long-term environmental damage from warfare has a lengthy pedigree, for example the long-lived heavy metal contamination from former WW1 battlefields,2 public pressure and political will to tackle the issue has fluctuated markedly during the last 50 years.

Pressure for progress has often intensified in the wake of specific conflicts such as the Vietnam War or the 1991 Gulf War. Yet while the wars in south east Asia contributed to the development of the ENMOD Convention[3] and the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions[4],3,4 these have been shown to be largely ineffective in minimising wartime environmental damage and do nothing to help deal with its aftermath.

The environmental impacts of conflict are diverse and highly variable from one setting to the next. In the absence of any meaningful development of effective legal protection during the latter part of the last century, a number of pragmatic ad hoc environmental responses were developed by UNEP and other actors. These have largely focused on assessing and restoring damage. In spite of UNEP’s work, and the challenges it has encountered in the often politically fraught aftermath of conflicts, the environment, and the humanitarian consequences of wartime damage to it, continue to struggle to get the attention they deserve from the international community, with serious consequences for civilian populations in conflicts around the world.

The new discourse

In 2009, UNEP published a major study on the state of legal protection for the environment in relation to armed conflicts.5 It made a number of recommendations on where improvements should be made. It was followed in 2011 by a report to the 31st International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent that formed part of its study on Strengthening Legal Protection for the Victims of Armed Conflicts,6 in which the humanitarian imperative for minimising and restoring wartime environmental damage was presented. Interestingly, the report proposed new tools for monitoring damage and environmental violations of IHL. The report concluded by suggesting that a new system of environmental assistance could be developed, modelled on those used to deal with explosive remnants of war (ERW). The Nordic governments and Red Cross societies pledged to undertake further work on the topic and report back to the 32nd conference in December 2015.7

Following a recommendation in UNEP’s 2009 report, the topic was also accepted for review by the International Law Commission (ILC), a study that will be completed by 2016. Special Rapporteur Dr Marie Jacobsson’s work on the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts has divided the topic into three phases – before, during and after armed conflict and is examining the relevancy and applicability of a range of existing legal regimes, such as International Environmental Law (IEL) and Human Rights Law (HRL). The ILC process mirrors several decades’ worth of informal debates by a range of legal experts on whether these regimes could provide greater protection for the environment than currently exists under IHL. Openness to the idea of utilising parallel bodies of law has subsequently emerged as a key test of whether states are progressive or regressive over the question of improving legal protection.8

In many respects this development is unsurprising. Environmental law has evolved at a far greater rate than IHL in recent decades. For example, the Precautionary and Polluter Pays principles have become the foundation for a number of international environmental agreements; creating obligations that the ILC has found do not necessarily terminate with the outbreak of hostilities.9

New developments have also taken place at the intersection of HRL and the environment,10 with increasing recognition of the role that a healthy environment plays in supporting the fundamental rights to health, life and livelihoods. One key aspect of this is the right to environmental information that may affect those basic rights, which in turn helps support access to effective remedies and participation in environment decision-making. Taken as a whole, this is fertile ground for debate which, thanks to the work of UNEP and others, can now be informed by the field experience from the environmental impact of historical, recent and ongoing conflicts.

The recent efforts of UNEP, the ICRC and the ILC are creating the space for a new discourse on strengthening protection for the environment in relation to armed conflicts. Unlike previous initiatives, the new discourse has not been the result of a particular conflict or incident but instead appears to represent a more sustainable consensus on the inadequacy of current legal provisions and the necessity of change.

Scope of this report

Historically, and in spite of the breadth of the topic’s scope, there has been a tendency to seek single overarching solutions to “conflict and the environment” and the feasibility of such complex approaches has been a matter for debate. Meanwhile, and in the absence of a clearly defined system of post-conflict environmental assistance, or a single forum for scrutinising damaging behaviours, international responses to wartime damage have become fragmented. Tackling the relationship between natural resource management and peace-building is perhaps the most obvious example, with a number of initiatives on timber, metals, diamonds and water emerging in recent years.11

In some respects, fragmentation has been a welcome development as it has allowed the clarification of messaging and the compartmentalisation of possible legal and policy responses. Yet where a topic suffers from low prioritisation, as is the case with the environment, it still seems desirable to create a system that helps tackle the issue of prioritisation head on by providing the political space where all forms of wartime damage can be addressed.

This report primarily focuses on one of the recognised forms of wartime environmental damage that carries with it direct threats to civilian health – conflict pollution.12 Yet some of its proposals could also be of relevance to wider questions of how other forms of wartime environmental damage could be minimised, assessed and addressed. This reflects the reality that many common post-conflict problems, such as poor environmental governance, not only influence the risks from conflict pollution but also cross-cut a number of other post-conflict environmental protection issues.

The report seeks to highlight where the elements of the hypothetical system examined in the report may also be utilised for addressing other forms of environmental damage but for the sake of brevity these are not considered in detail. However, we would welcome debate on their utility from experts and practitioners in relevant fields.

Environmental pollution in contemporary conflicts

The conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine, Iraq, Syria, and Libya have all created civilian health risks from environmental contamination. In Gaza the inadequate management of contaminated rubble continues to threaten public health and water supplies.13 In Ukraine and Libya,14 damage to industrial facilities, and with it soil, air and water pollution has been widespread. In Iraq, Islamic State is suspected of deliberately releasing industrial chemicals into watercourses, while the prolonged instability is exacerbating pre-existing environmental problems from previous conflicts.15 The Syrian conflict has had direct and indirect consequences on environmental quality. These range from rubble and hazardous weapons residues, to the collapse of environmental management, to damage to industrial and oil infrastructure, to pollution caused by the proliferation of artisanal oil refineries with non-existent environmental controls.16

The environmental footprints of these conflicts are creating acute and chronic threats to the civilian population. It is yet another reminder that civilian protection cannot, and should not, be viewed as distinct from protecting the environment upon which people depend. As is clear from the continuing health and environmental legacy of dioxin in SE Asia, to the oil fires and depleted uranium of the conflicts in Iraq to the environmental costs of the bombing of industrial infrastructure in the Balkans, the problems of wartime environmental degradation and contamination are not new. What is changing is that in the coming decades, population growth, climate change and pressure over access to natural resources will all serve to increase the vulnerability of civilian populations to environmental damage. If, as seems likely, a degree of environmental damage is unavoidable during conflict, these factors underscore the urgency behind the need for new and creative policy approaches, approaches that can help minimise environmental contamination, that ensure recognition and assistance for those harmed and that encourage timely and effective remediation.

Challenges to the current system

To date, post-conflict environmental assistance of this sort has been characterised by relatively informal case by case approaches. Post-conflict environmental assessments (PCEAs) are generally undertaken by UNEP on the invitation of affected states – or more rarely, are mandated by UNEP’s governing body. The World Bank and UN Development Programme (UNDP) have also led or partnered on PCEAs in the past. Financial appeals for assistance and recovery funding are distributed in response to the outcome of assessments. Some of the funds required are pledged, overwhelmingly by the same small group of donors who may be largely unconnected with the conflict or damage caused, providing that the call is not drowned out by competing humanitarian issues as the media races from crisis to crisis.

However, at times there is a sense that UNEP’s arms-length position within the UN system and comparatively weak political mandate on matters of peace and security has made this crucial work difficult, and that a more formalised mechanism, of the sort proposed by the ICRC in 2011 may be desirable. Even in cases where environmental assistance has been effective, mechanisms to investigate and address the civilian health legacy of damage remain underdeveloped – limiting the ability to judge the humanitarian impact of damage, a crucial metric by which to judge the acceptability of particular practices.

In the cases where recognition and financial reparations for damage have been pursued, these have often been highly confrontational or at times heavily politicised. For example Serbia’s case against individuals from NATO countries at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia,17 or Lebanon’s pursuit of Israel for damages from the 2006 Jiyeh oil spill through UN General Assembly resolutions.18 A key test of the desirability of such approaches is their effectiveness in protecting civilians from the impact of environmental damage and whether they have created norms that have helped minimise damaging behaviours. While they may have set precedents, both positive and negative, to what extent have they served to minimise damage in future conflicts or ensured timely remediation? Could an alternative system be envisaged whose primary emphasis was instead on shared responsibility and collaboration, and as such help to depoliticise post-conflict environmental assistance?

Norm development

The final and related question is whether other elements of a hypothetical system of post-conflict environmental assistance, not linked to the pursuit of financial reparations, could also help promote norms that discourage environmental damage more effectively than IHL’s existing provisions do? As far as the conduct of states in international armed conflicts is concerned, the evidence from peacetime environmental regulation is compelling.19 Where legislative approaches have enforced monitoring and have also framed the limits of acceptable behaviour, with the threat of fines and reputational damage where those limits are breached, corporate practice has been modified.

Even in a system that avoids strict financial liability in a majority of cases, in favour of shared responsibility, behaviours could still be modified by transparency and the risk of reputational damage. For this to be effective it would require a significant increase in the monitoring and visibility of environmentally damaging incidents and their civilian impact. It would also require that information on the environmental and financial costs of remediation and restoration be made more visible than at present. Each would help contribute to a more cogent understanding of the environmental, humanitarian and economic consequences of particular activities and practices, in turn helping inform a global consensus over their acceptability.

The changing nature of conflict, and with it the rise in non-state actors, be they armed groups or private military contractors, poses a significant challenge to any attempt to develop new norms. In Ukraine, Iraq and Syria severe environmental damage has been caused by non-state actors. Serious consideration is necessary over how the need for environmental protection could be promoted among armed non-state actors – particularly the linked questions of reciprocity and the conduct of states.20 At present such groups are typically on the outside of compliance processes, when instead they should be brought in as key stakeholders. But perhaps the more pressing need is that resources are made available to protect civilians and ensure communities affected by the environmental damage wrought by conflicts are assisted – regardless of who bears responsibility for causing that damage. Again an overly confrontational approach, which focuses on strict state liability above shared responsibility, may run counter to this objective.

While the relationship between environmental legislation and norm development is well established in the civil sphere, it is less well defined during conflict, in part because of the weakness of existing legal protection. There is a notable disparity between the environmental policies and practice of state militaries in peacetime with those in active operations, where operational success remains the pre-eminent consideration.21 Nevertheless, while the extent to which environmental considerations are recognised varies between militaries, practice is increasingly demonstrating that domestic military behaviour can be modified for the better where regulatory systems are in place.22

The behavioural ceiling created by the military’s perceived need to ensure mission success presents an enormous challenge to any attempt to minimise wartime environmental damage but improved monitoring and scrutiny of the environmental, health and financial costs of particular behaviours could contribute to the stigmatisation of particular practices, and ultimately more detailed consideration by states of the reputational costs their actions may incur.

Conclusion

It is now beyond doubt that progress on strengthening the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflict is long overdue. As history suggests that some damage to the environment is inevitable during warfare, these efforts should primarily be focused on addressing the consequences and protecting civilians. However, if parties to a conflict are conscious that the environmental aftermath of conflict will be dealt with at minimal reputational cost, this would only serve to help justify damage in pursuit of mission objectives. Therefore the final question relates to how systems of post-conflict environmental assistance can be utilised to deter damage and reinforce norms against the most environmentally harmful military practices.

This report seeks to identify the possible elements necessary for such a system and their basis in other fields of environmental, human rights or disarmament agreements. It is intended to be neither exhaustive, nor prescriptive but as a contribution to the ongoing and welcome debate initiated by UNEP in 2009.

Basic principles and our approach

Current efforts to examine new means through which the environment and its civilian population could be better protected have benefitted considerably from the debate among legal experts during the last few decades. This debate has been characterised by discussion over how parallel bodies of law could be used to provide greater environmental protection than that currently provided by IHL. This observation has now become a core element of the ongoing debate. For example, the need to consider parallel legal regimes was proposed by the ILC in 2014,23 and this was subsequently supported by a number of states,24 although acceptance is not currently universal.

It has long been recognised that IHL’s existing provisions are inadequate, poorly defined and as a result, inconsistently applied.25 Meanwhile the changing face of contemporary warfare is diminishing their utility even further. Furthermore, acceptance that the outbreak of hostilities does not terminate existing obligations under HRL,26 or IEL gives further credence to the view that, in the absence of effective protection under IHL, examining HRL and IEL for guidance in designing a new system of environmental assistance is justified.

Principles derived from Human Rights Law

An exercise to map and define the interrelationships between HRL and the environment was initiated by the UN Human Rights Council in 2012,27 with Prof. John Knox appointed as Independent Expert on the issue of human rights obligations relating to the enjoyment of a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment. His first report, published in 2013, confirmed that the principle that “environmental degradation can and does adversely affect the enjoyment of a broad range of human rights” was firmly established among states.28 This echoed the view of the Council itself, which had previously acknowledged that: “…environmental damage can have negative implications, both direct and indirect, for the effective enjoyment of human rights”.29

While this may seem self-evident, it serves as a reminder that the fates of the environment and its civilian inhabitants in wartime are inextricably linked, thus efforts to protect one should not proceed without consideration of the other. A number of obligations are particularly relevant in this context: the obligation to assess environmental impacts and make environmental information public; the obligation to facilitate public participation in environmental decision-making, including by protecting the rights of expression and association; and the obligation to provide access to remedies for harm. These will be considered in more detail in Section 3.

The principle of non-discrimination and its obligations to societal groups in vulnerable situations is also of value and will be considered in Section 4. For example, it is commonly the case that those with least political capital and social mobility bear the brunt of environmental degradation. Meanwhile the relationships between environmental contaminants and reproductive health, the unborn and childhood development, requires consideration of how harm is assessed and how remedies are developed and implemented. In particular it underscores the necessity of gathering age and gender disaggregated data as a means of ensuring that vulnerable groups are properly identified.

Principles derived from International Environmental Law

In addition to evaluating where a rights-based approach could be utilised for post-conflict environmental assistance, considerable value can be found in the principles and norms established by IEL. In this we have departed from a strict legalistic approach that considers the applicability of different legal regimes in a given context. A new system should not be reliant on whether a conflict-affected state has ratified specific environmental agreements, nor should it be at the mercy of debates over their applicability. Instead a new system should derive specific core principles from IEL and be informed by the normative and customary value of state acceptance of the requirements of particular treaties relevant to environmental protection and recovery.

As an example of this approach, Section 1 considers how the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants approaches international assistance and cooperation, while Section 2 reviews how liability and responsibility for harm is assessed under the MARPOL Convention, as well as the utility of the Polluter Pays principle. Section 6 considers how the 2003 Protocol on Strategic Environmental Assessments, and the functional aspects of Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) could inform the foundation of an inter-governmental review body on wartime environmental damage.

Principles derived from disarmament law

The next sources that we analysed for guiding principles were the international agreements on anti-personnel landmines,30 cluster munitions,31 and explosive remnants of war.32 The ICRC’s 2011 proposal that a new system of environmental assistance be devised, akin to that of CCW Protocol V, has merit and, while there is considerable criticism of the effectiveness of the Protocol V regime,33 there are elements of the protocol that are potentially transferrable. For example Article 9 on generic preventative measures could inspire the flexible scope necessary for a review body (see Section 6). Similarly the Convention on Cluster Munitions’ articles on victim assistance, transparency and international assistance and cooperation could help guide the development of community environmental assistance programmes (Section 4).

Rationale behind this approach

We believe that the wide international acceptance of many of the principles used in this report, albeit in a variety of contexts, justifies their use as a tool kit of principles, norms and precedents that, with modification, could inform a framework around which a new system of environmental assistance could be devised. For a topic as complex as conflict and the environment has proved to be, creativity is a necessity, not a luxury, and without an open-minded approach to inform future debate, the current initiative that began in 2009 may be doomed to repeat the failures of those that preceded it.34

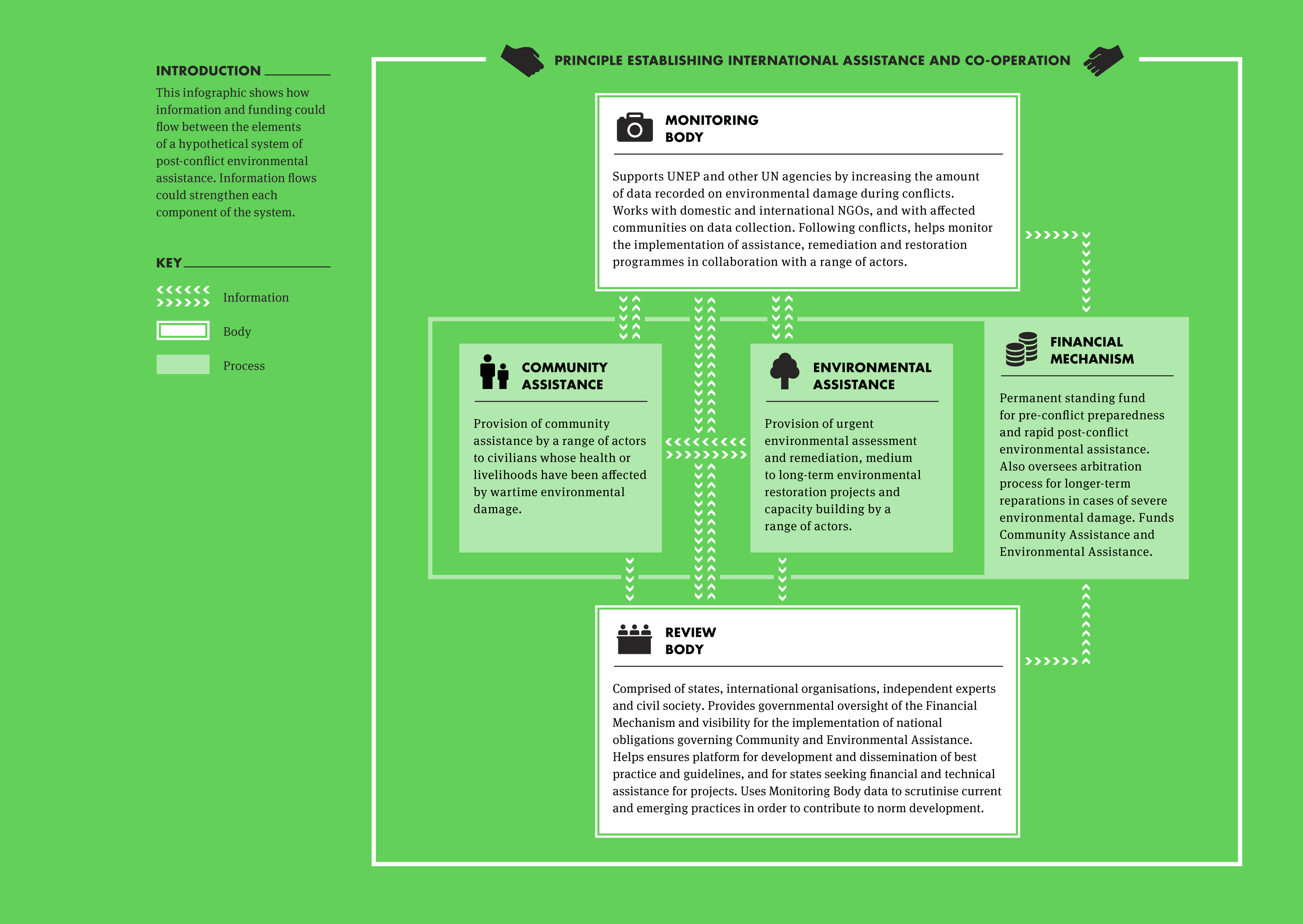

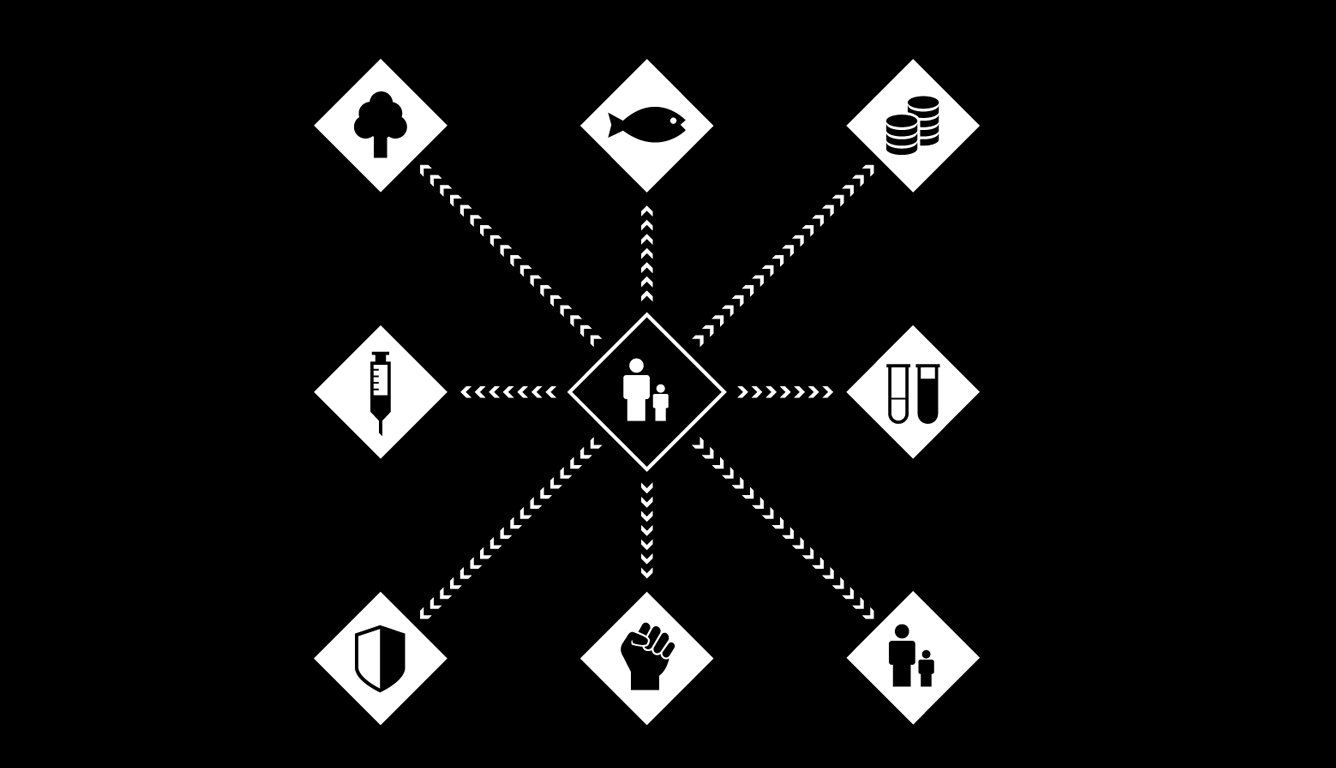

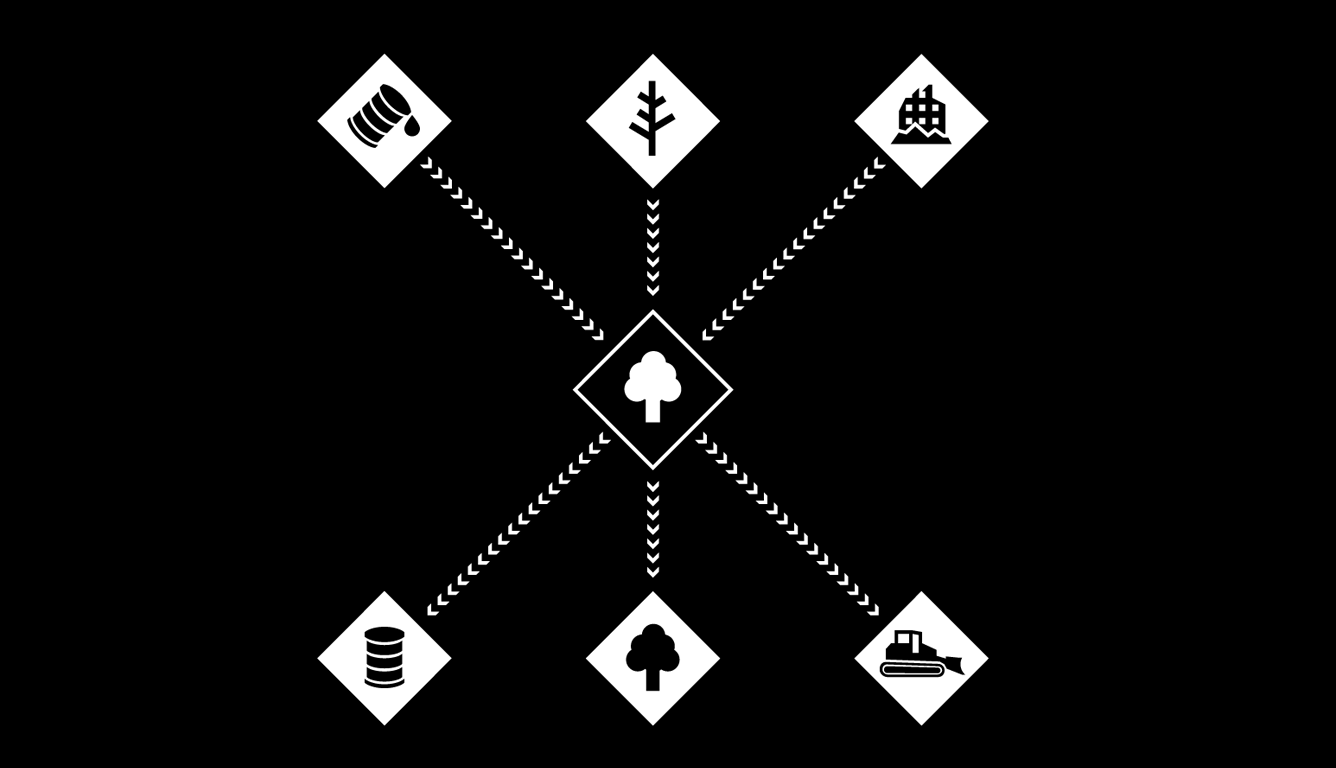

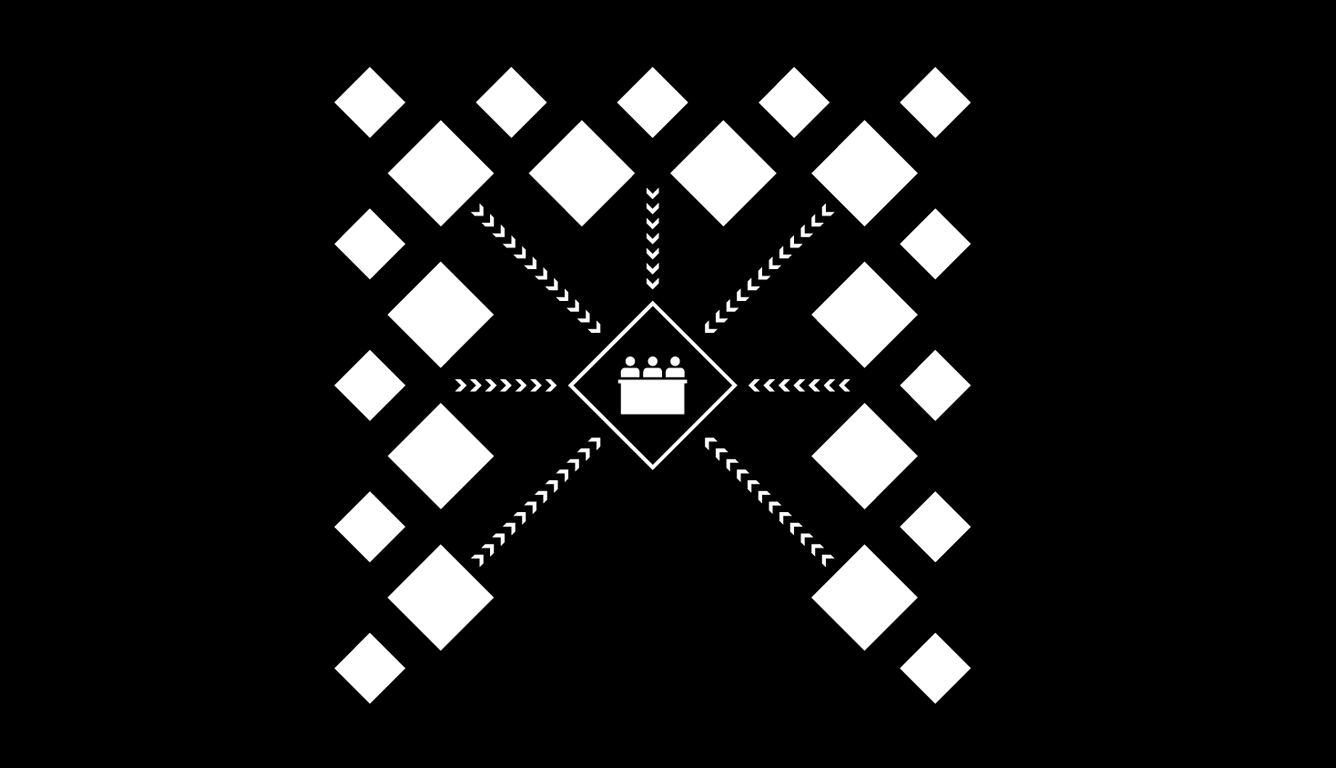

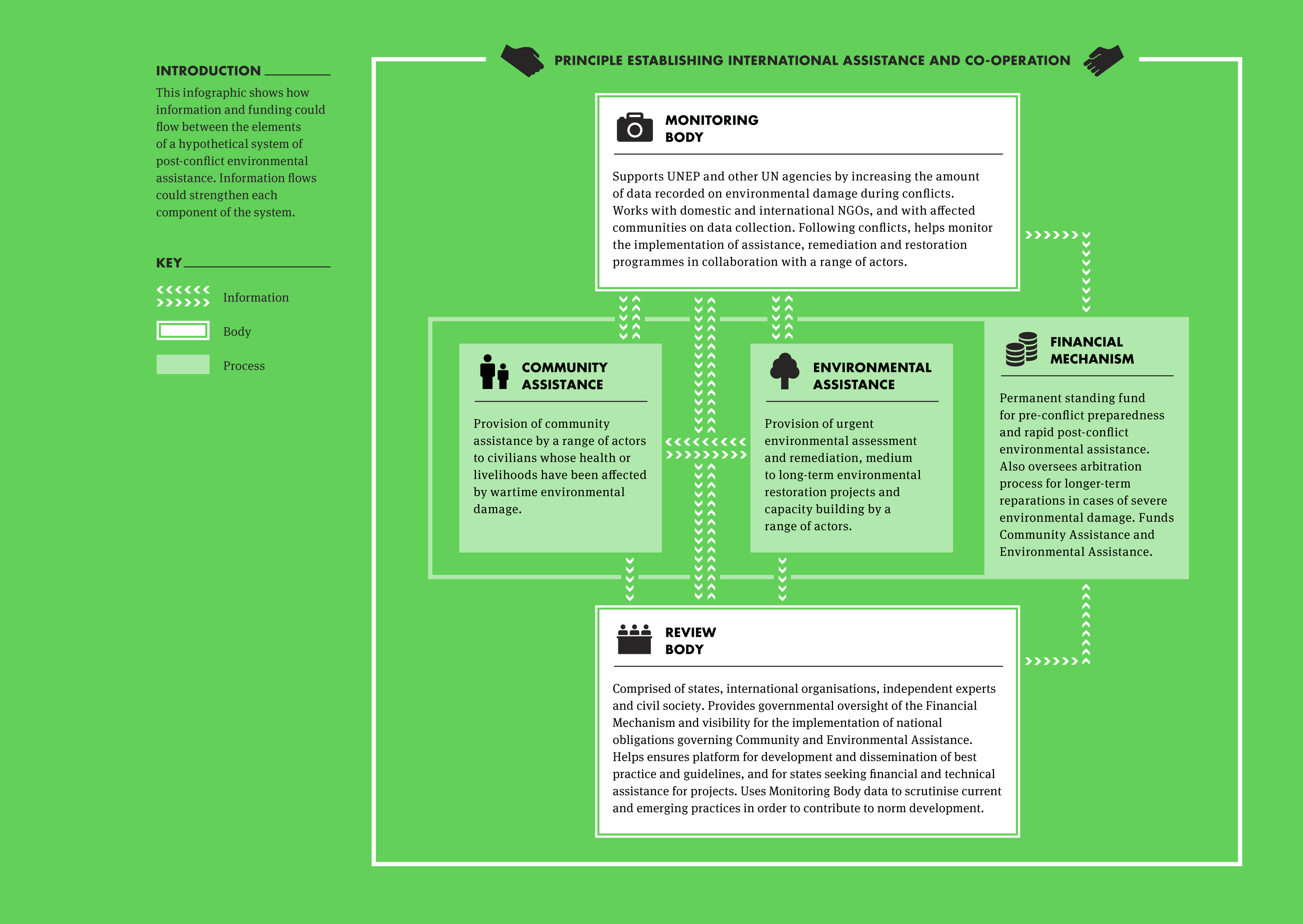

Interactions between structural elements

The elements suggested in this report are based on existing gaps in both policy and response. They are designed to interact with one another as parts of a whole, bound together by flows of information and knowledge. A graphic mapping the flows and interactions discussed in the six sections is available at the beginning of this section.

1.0 International assistance and cooperation

What would be an appropriate model for establishing the principle of international assistance and cooperation with respect to managing wartime environmental damage?

The founding principle for any new standard, be it formal or informal, must be that states are entitled to seek, and receive, international assistance in dealing with the environmental legacy of conflicts. To some extent this principle has already been established through the work of UNEP’s Disasters and Conflicts Sub-programme, whereby states can formally request a post-conflict environmental assessment, post-crisis technical assistance or support for environmental cooperation for peacebuilding. However this alone does not guarantee the transfer of technical, material or financial resources from the international community to implement these forms of assistance. How could new models ensure that implementing actors such as UNEP are properly resourced?

International assistance and co-operation feature prominently in most IEL and disarmament agreements where states affected by environmental problems, or ERW, require assistance in order to comply with treaty obligations. Many of these treaties contain articles placing either voluntary or mandatory obligations on states parties to co-operate with and assist other states parties. The overarching objective of such agreements is to seek to reduce inequality in the international system and ensure effective treaty implementation.

1.1 Assistance models in environmental agreements

Different environmental treaties approach the question of assistance in different ways. For example the Basel Convention’s Technical Cooperation Trust Fund focuses on assisting developing countries and other countries in need of technical assistance in the implementation of the convention.35 Similarly, the London Convention and Protocol obliges states parties to support technical co-operation to developing countries in support of the convention’s aims, primarily through encouraging technology transfers and promoting access to expertise.36

The Stockholm Convention again emphasises the need to provide assistance to developing countries. Article 13 of the convention requires economically developed state parties to provide financial resources to developing state parties, and parties with economies in transition, to help meet the costs of fulfilling the obligations of the convention. Article 13 also states that a financial mechanism is to be developed to facilitate implementation, with the UNEP administered Global Environment Facility (GEF) being used in the interim.37

It is specifically noted by the Stockholm Convention text that the ability of developing countries to meet the obligations of the convention will depend on developed country contributions; importantly it also notes that developing countries have a range of competing national priorities, such as poverty eradication, sustainable development and social development that should take priority.38 The Stockholm Convention’s recognition of the prioritisation challenges faced by developing counties, and its balancing of these needs with the human health and environmental threats posed by persistent organic pollutants could set a useful precedent. Yet it is also worth noting the impact that wartime environmental degradation and infrastructure damage can have on efforts to achieve these competing goals, particularly sustainable development.39

The parallels with post-conflict states affected by wartime environmental damage and conflict pollution are clear. While there are undoubtedly immediate priorities facing post-conflict states, which are additional to the many development priorities that they may also face, the long-term health and environmental threat posed by conflict pollution and environmental damage is an important issue that must also be addressed. As such, the ability to call on the resources of wealthier states to help deal with these issues is essential.

1.2 Assistance models in disarmament agreements

The CCM takes a slightly different approach to international assistance and co-operation to those in the IEL treaties above, with Article 6 of the CCM noting that all state parties have the “right to seek and receive” assistance. In the context of the CCM, assistance not only covers the marking and clearance of cluster munitions but also stockpile destruction and, critically, victim assistance. The obligation on all state parties to maintain the rights and needs of victims is a central pillar of the CCM, a stricture that evolved from the Mine Ban Treaty (MBT).

Unlike many IEL treaties, the CCM does not classify state parties as developed or developing. Instead it notes that there are obligations on all states “in a position to do so” to provide assistance and co-operation.40 In addition three aspects of assistance are highlighted: technical, material and financial and the convention seeks not only to promote north to south transfers of financial assistance, but also north to south, and south to south transfers of technical and material assistance.41

1.3 Implementing assistance

While the agreements outlined above provide principles that could help inform assistance and co-operation models for a new system of post-conflict environmental response and recovery, they would only be effective if matched with the institutional capacity necessary to ensure implementation.

The logical entities to deliver environmental and health assessment and rehabilitation in conflict affected states would be the pre-existing national ministries of health and the environment. However the damage caused by conflict to systems of environmental governance is well documented. Furthermore, environment ministries often suffer from inadequate resourcing and low prioritisation in both stable and fragile states, which can leave them in a particularly parlous condition following conflicts.

Similarly, health ministries also face numerous challenges in states recovering from conflict. Hospitals and clinics may have been destroyed or may be overwhelmed by acute health problems and population movements, workers face shortages of equipment and medicines, water and sanitation systems may be damaged and core staff may be forced to flee.

Given these problems, it may be desirable to consider whether temporary or medium-term national centres could be created in order to channel technical, material and financial resources to assessing environmental and civilian harm and overseeing community assistance and environmental rehabilitation projects. These could be led by the state in partnership with international organisations, or where the state initially lacks capacity, by international organisations alone.

UNEP’s national environmental capacity building offices provide one possible model, as do the national and regional centres created by the Stockholm,42 Aarhus,43 and Basel conventions.44 From ERW come the examples of the national mine action centres, which act as focal points for national clearance efforts. In this they collaborate with national, commercial and humanitarian demining entities and it is possible to imagine how similar structures could be established to oversee environmental assessment and remediation work by private sector or NGO actors.

Taken as a whole, structures similar to these could prove invaluable in coordinating the implementation of assistance programmes, ensuring knowledge and technology transfers and providing a measure of transparency and accountability. Importantly, their aim throughout the lifespan of projects should be to support and reinforce, rather than replace, national institutions.

1.4 Conclusion

Models of international assistance and cooperation exist in a number of relevant regimes. The sample above is in no way exhaustive, providing as it does only a taste of the different approaches taken. How environmental and community assistance should be prioritised, funded, delivered and overseen in a way that ensures that human rights and the environment are afforded the highest levels of protection will require consideration. But the principles of assistance and cooperation between states on environmental or weapon contamination challenges are well established.

A further point to consider is how the guarantee of international assistance and co-operation could be used to incentivise membership and universalisation among states in a system of environmental assistance. Conversely, safeguards may be needed within such a system to ensure that the knowledge that damage will be dealt with does not incentivise or perpetuate environmentally harmful military practices.

2.0 Financing and liability

What is the best way of ensuring that urgent funding and technical assistance is always available to states affected by wartime environmental damage?

The question of who should pay for post-conflict environmental assistance is as critical as it is controversial. Environmental remediation programmes can be technically challenging and costly. Yet where systems defining liability and accountability have been developed in the civil sphere, avoiding the financial risks these regulatory frameworks create has often encouraged behavioural changes among polluters. But is military or state practice as responsive to the threat of financial liability as that of corporate practice?

At present there is no properly established system for financing post-conflict environmental assessment, assistance, remediation or compensation. Approaches to date have been ad hoc and, as a result, often inadequate. A distinction appears to be emerging between urgent emergency environmental assistance and reparations or compensation over the longer term. However, precedents remain far more prevalent in IEL than for wartime environmental damage and this section will consider several approaches that could help inform how a new system of assistance could be financed.

2.1 Reparations under International Humanitarian Law

The ICRC’s analysis of customary IHL suggests that states responsible for violations of IHL are required to make full reparation for the loss or injury incurred by these violations.45 Reparations have been sought both by states and individuals for wrongful acts. Individuals can and have sought claims for the loss or damage to property through various means, such as through inter-state agreements, of which one pertinent example was the UN Compensation Commission (UNCC), which was established in 1991 to process claims for compensation against Iraq from the 1991 Gulf War.46

Iraq remains the only state to have been held to account and forced to pay reparations for environmental damage in wartime. In 1991, the UN Security Council (UNSC), passed resolution 687, in which it was stated that Iraq was found liable for, among other things, ‘environmental damage, and the depletion of natural resources’, as a result of its invasion and occupation of Kuwait.47 This led to the establishment of the UNCC, which adjudicated the subsequent compensation claims. This was made possible by the ability of Iraq to pay successful claimants, as a substantial percentage of Iraq’s oil revenue was diverted to enable payments.48

The UNCC set a useful precedent for enforcing wartime environmental liabilities. Not only were the procedural aspects of assessing claims and placing a valuation on environmental loss a valuable exercise, it also established that the UNSC is able to hold states to account for significant wartime environmental damage, when willing to do so. The political context behind the UNSC resolution was that the 1991 Gulf War ended with Iraq on the losing side and key states on the conflict’s winning side sat on the UNSC.

The UNCC relied on jus ad bellum, the UN Charter and state responsibility as a legal basis for reparations, rather than jus in bello. This was primarily because the states involved were not party to the relevant treaties but also because jus in bello would not have provided a sound legal basis upon which to assess damage. However this meant that the UNSC did not specify the environmental provisions of IHL that were violated.49 Instead the UNSC based its judgment on Iraq on its reasons for going to war – the unlawful invasion, as opposed to its actions in war, such as the setting of oil-well fires. Some argue that an opportunity to set a legal precedent for enforcing responsibility for environmental damage during conflict was lost,50 while others argue that the legal precedent set would have been that it is possible to destroy the environment during armed conflict with impunity.

Individuals may also be compensated through unilateral state acts, such as national legislation, and through national courts, although in many cases these have not been successful as states have at times argued sovereign immunity.51

Given current IHL’s current inability to effectively protect the environment and the environmental rights of civilians,52 for customary rule 150 to be used effectively in relation to environmental damage, the existing IHL rules relating to environmental protection would have to be strengthened, or at least clarified – something that seems unlikely at present.53 And while specific practices or weapons use by military actors have direct environmental impacts, environmental and humanitarian impacts of conflict regularly occur that are not directly attributable to the behaviour of parties to a conflict but to the capacity and ability of affected states to maintain basic environmental services.

These indirect environmental problems may result from the breakdown of environmental governance, for example, the collapse of waste disposal services,54 or in hazardous industrial sites being left insecure and open to looting.55,56 Under normal circumstances, the local or national government would be responsible, but during both internal and international conflicts, governments may be in flux or unable to take responsibility. This suggests that it is essential for obligations around responsibility to go beyond requirements based on IHL violations.

2.2 Rights and duties

A more recent trend in disarmament law has been to utilise a rights-based approach to define post-conflict obligations. The CCM established obligations for cluster munition clearance and stockpile destruction. These obligations identify the host or affected state as the primary duty bearer for upholding the human rights of its population. The affected state is thus responsible for ensuring clearance takes place, regardless of who used the weapons on its territory.

The CCM and the MBT’s approach has been to separate user (of weapons) responsibility from clearance obligations. In the CCM, user states (if party to the convention) are “strongly encouraged” to support host states in cluster munition destruction and clearance.[notes]CCM (2008b Article 4)[/notes] By holding the state in which contamination is present responsible, rather than those that may have used the weapons, the treaties seek to diminish the corrosive influence of the politics of accountability and highlight the necessity of protecting civilians. Within the CCM, systems are put in place to support affected states in fulfilling their duties. For example, Article 6 on international assistance and cooperation encourages the provision of expertise and assistance for affected state parties.

Transferred to the context of wartime environmental damage, a rights-based approach could mean that states party to an environmental assistance system would be responsible for the environmental rights of their own citizens. This obligation could require them to provide baseline data on pre-conflict environmental conditions, identify environmental risks stemming from the conflict, to plan for their removal and implement appropriate projects, together with the assistance of the international community. It could also require that they have policies in place to measure health and social impacts, to reduce harm through community assistance programmes, provide effective national avenues for legal redress and to provide transparent progress reports. Although a number of regional fora exist that provide possible avenues for legal redress over human rights violations, and while many national constitutions written since the 1992 Rio Declaration have enshrined rights relevant to environmental protection, using these often underused avenues in relation to wartime environmental damage has been proposed as an interim measure only.57

2.3 Should the polluter pay?

While the framing of liability and the mechanisms for compensation vary between agreements, the need to ensure that the victims of pollution and environmental damage are compensated, and that someone is held financially liable for damage, is well established in IEL.

“States shall develop national law regarding liability and compensation for the victims of pollution and other environmental damage. States shall also co-operate in an expeditious and more determined manner to develop further international law regarding liability and compensation for adverse effects of environmental damage caused by activities within their jurisdiction or control to areas beyond their jurisdiction” Principle 13 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development.58

Within the civil liability for oil pollution regime,59 the owners of oil tankers are identified as the liable parties. This is the case whether polluting incidents occur through negligence or not,60 ensuring that those impacted do not have to prove that the ship owner acted negligently, only that they were impacted by oil pollution. In doing so it reinforces the rights of the impacted party and the environment by ensuring that the polluter contributes to the costs of remedying harm, although liability is exempted where damage is caused by acts of war or natural phenomena.61

To ensure the workability of this provision, liabilities faced by tanker owners are limited and they are required to hold insurance to cover this limited liability.62 However if owners are found to have been negligent, liability is unlimited.63 To ensure clean-up costs and the rights of those impacted by oil pollution are addressed in circumstances where costs exceed the limited liability of ship owners, the treaty also established a Fund Convention. This fund is paid into by states that receive oil by sea and provides for additional (if limited) compensation in the event that the limited liability of ship owners does not cover the costs of incidents.

The civil liability regime for accidents affecting the nuclear industry has a similar structure, in that strict (no fault) liability is placed on the operators of nuclear power plants, and an international fund (most of which is funded by states that use nuclear power) has been established to top-up this liability.64 However in this case, there is an additional actor – the state in which the nuclear plant operates – and this host state is required to make US$300m available as Special Drawing Rights in the event of a nuclear accident.65

Alongside the assumption that polluters should be held liable, there is an understanding in both the oil transportation and nuclear industries that risk is present, and that there should be liability for this risk, irrespective of fault. It could be argued that as conflict and military activities are inherently risky for the environment, parties to a conflict should also bear some responsibility for damage, whether intentional or not. Is it possible to determine specific damage thresholds beyond which actions are deemed negligent and subject to strict liability? Given how variable incidents, their causes and their negative environmental or humanitarian outcomes can be, this seems difficult. This suggests that a different approach is required, one that utilises robust field data on impacts and whether the incident contravened particular behavioural norms to inform processes to determine financial liabilities.

2.4 Rights and responsibilities

There are clearly pros and cons to these different approaches. By ensuring that the state is a duty bearer of rights for its citizens with respect to wartime environmental damage, and with the international community supporting that state to uphold these rights, the rights-based approach of the CCM would ensure that someone is obligated to ensure the rights of civilians are protected, and that they are assisted in doing so. On the face of it, a rights-based approach seems potentially less useful in protecting the environment per se, with environmental remediation only undertaken where there is a clear human benefit. Yet measures to protect rights to health, life and livelihoods would also extend to protection of those elements of the natural environment upon which the civilian population depends, be it water resources, timber or, potentially, biodiversity. This kind of approach, which focuses on the obligations on the affected state, may appear less controversial than one that clearly defines obligations and liabilities on the parties to a conflict.

Conversely, the approach taken by many environmental treaties requires that polluters be held directly responsible for compensating those impacted and for remedying environmental damage. If applied to a conflict context, such an approach would doubtless prove politically unpopular, yet clarifying liability in this way could have a powerful normative effect. The experience from the civil sphere and IEL suggests that this kind of legislation strongly disincentivises polluting practices, encouraging the search for less risky and more environmentally responsible alternatives.

A further problem with the traditional IEL approach that holds polluters liable is that it requires both parties to be clearly identifiable legal entities. The majority of contemporary conflicts are internal or non-international armed conflicts. The armed groups and non-state actors involved in non-international conflicts make for problematic targets for the pursuit of liabilities for a number of reasons, suggesting that a different approach is needed. Similarly, in many cases, identifying the polluter directly responsible for the complex polluted environments created by conflicts can be problematic. A rights-based approach could help sidestep this identification problem.

The final challenge is a temporal one. Any new system that seeks to minimise civilian and environmental harm must be able to respond quickly to damage, particularly to acute threats. It cannot afford to wait for years for legal processes to conclude before resources are made available. The UNCC’s claims handling process for environmental damage and losses connected to harm provides a useful template for assessing claims but the process took around six years to complete.

Similarly, the experiences from UNEP’s fundraising for post-conflict assessments, whereby appeals are made to the international community to finance work on a case by case basis, suggest that funding for urgent response must be made more structured, so as for them not to be reliant on the whims of donor interest. Equally, the responsibility for funding assessments has often fallen on a small group of repeat donor nations who often have no direct link to the conflict or to the damage caused.

The recent conflict in Libya is a case in point. UNEP was invited into Libya by its government to undertake an assessment of a conflict that has seen a number of significant environmental incidents, including widespread damage to its oil industry. However, insufficient donor support was forthcoming and as of the time of writing, no assessment has been undertaken, in spite of the considerable risks such incidents may pose to Libya’s civilian population and environment.

2.5 Acute response, norm-building and long-term assistance

The precedents, approaches and problems briefly outlined above would appear to suggest that a new system should take a twin-track approach to financial assistance for wartime environmental damage. The first of these must be a permanent emergency fund to support initial post-conflict environmental assessments, emergency responses to acute threats and to initiate capacity building. To depoliticise the fund and environmental responses, states party to a new system could contribute into it on the basis of GDP or a similar measure. The ability to access this “environmental solidarity” fund in the event of conflict could perhaps serve as an incentive to join the system.

To fund environmental remediation, restoration or longer term community assistance programmes that are identified as necessary during the assessment phase, a second approach might be required. Historically, the discourse has focused on confrontational systems that would have a strong normative deterrent effect, for example UNEP’s 2009 proposal of a:

“…permanent international mechanism to monitor legal infringements and address compensation claims for environmental damage sustained during international armed conflicts”.66

Lebanon’s ineffective pursuit of Israel over the 2006 Jiyeh oil spill has shown how easily adversarial processes can become mired in politics. If existing routes for redress become bogged down in this way they clearly do little to help civilians and their environment. The powerful normative impact of the system proposed by UNEP could help deter future harm but could deterrence also be achieved through other means? This will be discussed in Section 6.

The experiences from the regimes dealing with ERW, is that more consensual approaches are not only more politically palatable in the first instance but may also be more effective in ensuring funding for assistance and clearance programmes in the longer term. This still represents a compromise, as doubtless a more muscular system of restitution could be more effective still, although such an ideal seems politically unrealistic.

As noted above, a rights-based approach that places obligations on the affected state to uphold the rights of its citizens, on the basis that assistance will be made available from other state parties to the agreement, could form a fundamental element of a new system of environmental assistance. By not focusing on the party responsible for the damage but instead dealing with its humanitarian and environmental consequences, a rights-based assistance system would be able to deal with international and non-international armed conflicts alike.

However, the costs of some remediation and restoration projects may far exceed the typical costs of ERW clearance programmes. In these cases, typically but not exclusively international armed conflicts, it may be necessary for agreements to be reached elsewhere. UNEP proposed the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration,67 where states and panels of experts could reach agreements over liabilities for damage. Thought would be required on the financial threshold beyond which a process should be triggered and this should be informed by past examples of severe wartime damage. Other fora should also be considered but it seems important that one standing forum is identified for this purpose, that processes should be independent and depoliticised to as great an extent as possible, that decisions should be based on solid scientific data on the damage caused and it should make sure that decision-making is streamlined.

2.6 Conclusion

Designing a new financing and liability system for wartime environmental damage is complex. Peacetime and post-conflict precedents could be useful in guiding such a process but focused work will be needed to ensure that new models are both more practicable and effective than the current ad hoc system.

Regardless of how well designed they are, bodies established to rule on questions of strict liability will always be too slow and cumbersome to ensure financial assistance for acute threats and urgent assistance, not least because they will require detailed information on the damage in question. Thus more focus is needed on permanent structures that can ensure that financial support is always available for rapid post-conflict response. Such a system should be guided by the need to provide the highest standards of civilian and environmental protection. In doing so it needs to provide for immediate assessment and risk reduction but also to prepare the foundation for environmental needs over the medium-term, for example by initiating and supporting capacity building.

Nevertheless, longer-term systems to determine liability for damage should not be entirely excluded from consideration as they could play a valuable role in deterrence and norm development. If combined with more effective monitoring of damage, more comprehensive information on the humanitarian and environmental consequences of incidents and the financial costs of remediation and restoration, such a system could help make damage, and the behaviours that cause it, far more visible than at present.

3.0 Monitoring and information

How can we increase the amount of information that is gathered on the human and environmental impact of wartime damage?

The UN Secretary General’s 2014 observation that the environment is a “silent casualty of war and armed conflict”,68 does much to explain the root cause of the international community’s collective failure to adequately address wartime environmental damage, and the threats it poses to civilians. As noted in Section 6, the environment struggles to get on the agenda at the best of times, and with a few dramatic or photogenic exceptions, the environmental impact of warfare is usually relegated to footnote status.

The need to properly record wartime damage is vital for developing responses that protect civilians and for minimising harm to the environment. It is vital for the development of our understanding of the acceptability of particular military practices and in the formation of new behavioural norms. Furthermore the collection and transmission of information on environmental risks forms the foundation of effective community assistance and with it, the safeguarding of human rights. However governments may be a serious obstacle in any efforts towards ensuring greater transparency as economic, legal and political considerations can all make states reluctant to release environmental data that may identify health or environmental threats.

Nevertheless, new tools, methodologies and opportunities for gathering data on both conflicts and environmental damage are constantly being developed. This information will be critical for creating the political imperative to improve on current systems of post-conflict environmental assistance. If this can be achieved, a robust and independent monitoring body would also be essential for the operation of a new system.

3.1 The status quo

“In the typical post-conflict situation, historical data are lacking, environmental monitoring is sporadic, and interagency coordination (assuming that agencies exist and are functioning) is poor to non-existent. And even where monitoring capacity exists, large scale environmental assessments require access to information, data exchange, and institutional transparency in settings often dominated by suspicion and exclusion” (Conca and Wallace 2012).69

Before considering what should be done, it is necessary to consider how data are gathered and used at present. UNEP undertakes limited monitoring work during major conflicts. Satellite data and remote sensing are used to record incidents, as are connections with environmental agencies on the ground. For some conflicts, such as Iraq,70 and Kosovo,71 UNEP has also issued preemptive warnings about specific types of threats in order to help inform Post-Conflict Needs Assessments at the earliest possible stage.

In the event that UNEP is invited to undertake a post-conflict assessment by an affected state following the conflict, and providing there is sufficient donor interest to fund it, monitoring data helps inform and guide the assessment. In certain cases, assessments have also been undertaken by the UNDP and World Bank, although the majority have been led by UNEP. The results of assessments may be published months, or in some cases years after the cessation of hostilities and not all conflicts are assessed in this way.

While thorough and increasingly refined, these assessments only provide a snapshot of the environmental conditions at the time of the assessment. This is particularly problematic for long-running conflicts such as those in Afghanistan or Syria. They are typically unable to say much about the pre-existing baseline environmental problems which may underlie more recent damage or about the health or environmental risks in the period between any given incident occurring and the assessment. At present there is little or no follow-up to assess health impacts or the efficacy of environmental interventions in the months or years following the assessment.

These limitations are due to a number of factors, including UNEP’s comparatively weak mandate on conflicts, the low prioritisation afforded to environmental issues following conflicts, the informal system of funding for assessments and the limited number of data points they can rely on. In some cases information sharing between UN agencies, and between national authorities and UN agencies, has been poor.72 At times conflict-affected areas have been off limits to international organisations over security concerns, in other cases ERW have left sites inaccessible.

3.2 Creation of a monitoring body

In 2009, and in recognition of some of these problems, UNEP identified the need for a “permanent international mechanism to monitor legal infringements”.73 The principle behind this remains sound but, as IHL provisions for the protection of the environment are weak – with unclear and unrealistic damage thresholds, any permanent body of this sort must take a broader view of harm. While the nature of damage and the risks it may pose to communities and the environment vary from conflict to conflict, past assessments have helped identify the types of problems that are likely to occur. Many of these would fall well below the poorly defined “widespread, long-term and severe” thresholds of current IHL but may nevertheless pose grave risks to the civilian population, to effective peacebuilding and to sustainable economic recovery of communities.

Given the importance that understanding the nature and scope of environmental problems associated with particular conflicts would play in any new system of environmental assistance, the question is who should be responsible for this monitoring role? The most obvious suggestion would be for UNEP to be mandated and funded to expand its existing work on conflict monitoring, but would the constraints of political neutrality, and with it the necessity of gaining field access for assessments, limit their voice, and by extension the voices of those affected?

3.3 Role of civil society

Typically, the mandates of secretariats established under the auspices of environmental agreements such as CITES,74 or the Basel and Rotterdam Conventions are limited to convening meetings, undertaking specific technical research when requested to do so by parties and supporting treaty implementation.75

The MBT and CCM take a similar approach, with both having an equivalent Implementation Support Unit for the treaties, which is supported financially by states parties.76 However, both CITES and the MBT and CCM make formal and informal use of civil society networks to provide oversight of the effectiveness of the regimes. For instance, CITES uses TRAFFIC,77 which is a partnership between the WWF and the IUCN. The MBT and CCM meanwhile use The Monitor, which was established to provide:

“…accurate and sustained reporting with respect to landmines, cluster munitions, and other ERW, and for monitoring the universalisation and implementation of the Mine Ban Treaty”.78

In both examples, civil society plays an important role in ensuring scrutiny of the regimes, the accountability of state parties and in providing the data that helps drive effective implementation. In each case, creating the civil society bodies was made easier by the fact that the NGOs forming them already had existing field and advocacy programmes on both endangered species, in the case of TRAFFIC, and ERW, in the case of The Monitor. This ensured that information on both implementation, and the problems the agreements were established to solve, was gathered from the field and could be collated and disseminated by the new bodies.

Does civil society currently have the capacity to fulfil such a supporting role for monitoring wartime environmental damage? Perhaps not to the same extent as the entities highlighted in the previous examples but the potential is there if national and international civil society organisations could be engaged and supported. This would require investment from states and other donors, particularly into how new observational tools and methodologies could be developed and deployed. Recent examples of what is already possible include the monitoring of damage to industrial sites and nature parks in the conflict in Ukraine in collaboration with domestic NGOs,79 and the monitoring of environmental contamination in the conflict in Syria.80

In addition to remote observation utilising satellite imagery, or online and social media sources, the TRWP is currently examining how the humanitarian and demining sectors could also contribute to the collection of environmental data on the ground during, and shortly after, conflicts. In turn this may also provide opportunities for civilian populations to become directly involved in data collection and dissemination. This could encourage ownership of environmental problems, help empower communities and help increase accountability on the national level, for example in helping to provide oversight and accountability for remediation programmes (see Section 5).

The importance of this potential role is underscored by the recognition that environmental ministries are often poorly resourced prior to conflicts. In many conflict-affected states, national systems for monitoring indicators such as air quality are often absent prior to the outbreak of hostilities, or may fall into disrepair during conflict. Not only does this limit the number of governmental data sources, it also hampers efforts to determine baseline environmental conditions, and therefore to calculate the impact of the conflict. Improving access to national baseline data and governmental monitoring systems will be considered in Section 6.

3.4 Information flows

Improvements to how we document wartime environmental damage are clearly overdue. But how should the data be utilised? Section 4 considers how it could be used to identify those harmed or at risk of harm, and how it could inform harm reduction measures. Section 5 looks at how it could be used to ensure community buy-in to remediation projects. This section and the final one discuss how it could both encourage buy-in from policymakers and ensure accountability and oversight of projects.

But one area that has not been mentioned is the way in which technical data from assessments can be used as a tool in peacemaking, where impartial information from a trusted source can be used as a confidence-building measure in order to engage stakeholders. But in circumstances where trust is low, and where there may be considerable anxieties over particular environmental threats, there may be pressure to promote a solely technocratic viewpoint at the expense of community involvement in decision-making. This approach has often been seen in official responses to pollution incidents in the civil sphere, where it can disempower affected communities and build resentment and distrust.

The Aarhus Convention has helped establish that states have a number of obligations in the fields of environmental assessment and environmental justice.81 For example the obligation on states to assess the environmental impact of activities and make environmental information public; the obligation to facilitate public participation in environmental decision-making, including by protecting the rights of expression and association; and the obligation to provide access to remedies for harm. In doing so it has done much to help define the relationship between access to environmental information and the protection of fundamental human rights.

Given that overtly technocratic top down flows of information can be counterproductive to community engagement and empowerment, should a new system of environmental assistance not only seek to enshrine the spirit of Aarhus in terms of its obligations on affected states but also set a new standard for community empowerment in environmental matters? On a technical level this might involve equipping affected communities with the tools and training to monitor their own environment. From a legal perspective and to increase accountability, it could require that states parties must guarantee access to justice and transparency and accountability mechanisms for environmental remediation and recovery programmes in their national legislation as part of ratification.

3.5 Conclusion

The collection and dissemination of information is critical for effective environmental protection. It will be critical for building political support for a new system of post-conflict environmental assistance and it would be critical for ensuring its effective implementation. Data gathering and dissemination are functions where civil society could play an important role, as they do in a number of other international agreements, provided that enough domestic and international organisations could engage on the topic – something that will require the support of the donor community.

Importantly, information could also help empower affected communities, encouraging engagement and ensuring that they can fully participate in environmental decision-making that affects their health and livelihoods. This means communities not just being the recipients of environmental information but also equipping them with the tools and training to gather information themselves. Just as the CCM established a new standard for victim assistance by merging powerful human rights provisions with disarmament law, could a future system of post-conflict environmental assistance set a similarly high standard at the interface of human and environmental rights?

4.0 Community assistance

How can we ensure that communities and individuals affected by wartime environmental damage or degradation are identified and assisted?

Many of UNEP’s post-conflict environmental assessments have reported pollution problems that could threaten civilian health but few, if any, follow-up or longitudinal studies have been undertaken to assess and document the impact of these problems. This section will consider how this could be remedied, based on victim assistance precedents sourced from disarmament agreements. In general, the health impacts of the environmental pollution or degradation caused by armed conflict are profoundly under-addressed at present. Therefore any new system intended to minimise and remedy environmental damage from armed conflict should also be rooted in the need to protect civilians, and in the need to assist those affected.

While identifying those who have been harmed, or are at risk of harm, is less straightforward than identifying the casualties of explosive weapons, it is not impossible, providing that the collection of data on wartime incidents and their associated environmental hazards can be improved. Likewise, significant improvements are needed in ways to integrate this data into post-war public health systems, which will also mean ensuring that ongoing technical support is made available to health ministries and other relevant actors.