Evidencing a recovery plan for Black Sea dolphins and porpoises

Published: December, 2025 · Categories: Publications, Ukraine

Many human activities pose threats to cetaceans, including military activities. Russia’s war against Ukraine is no exception and there are significant concerns over its impact on Black Sea dolphin and porpoise populations. Regional experts have proposed a recovery plan but as Linas Svolkinas explains, we need to understand conflict-linked threats before we can take meaningful actions to mitigate them.

Introduction

In December 2024, the scientific committee of ACCOBAMS1 — the intergovernmental body tasked with protecting cetaceans in the Black and Mediterranean seas, and parts of the Atlantic — recommended for consideration of the parties a post-war recovery plan for Black Sea cetaceans affected by Russia’s war against Ukraine. There are fears that the war has had a substantial impact on dolphins and porpoises in the Black Sea, with frequent media reports of deaths and strandings. As apex predators, their fate is intimately linked to the wider marine ecosystem, and to the livelihoods that it supports.

Cetaceans are dependent on sound for feeding and communication, therefore acoustic pollution, which can be generated by multiple sources of underwater noise like blasts and sonar, is often the primary concern for conservationists when populations are affected by military activities. However, the ACCOBAMS plan casts its net wider, proposing research on:

‘…marine pollution, eutrophication, increased risk of infections, increased risk of bioinvasions of alien species, and other effects’, plus indirect activities associated with the war, such as ‘construction works (especially those producing underwater noise or altering the seascape) or changes in shipping routes.’

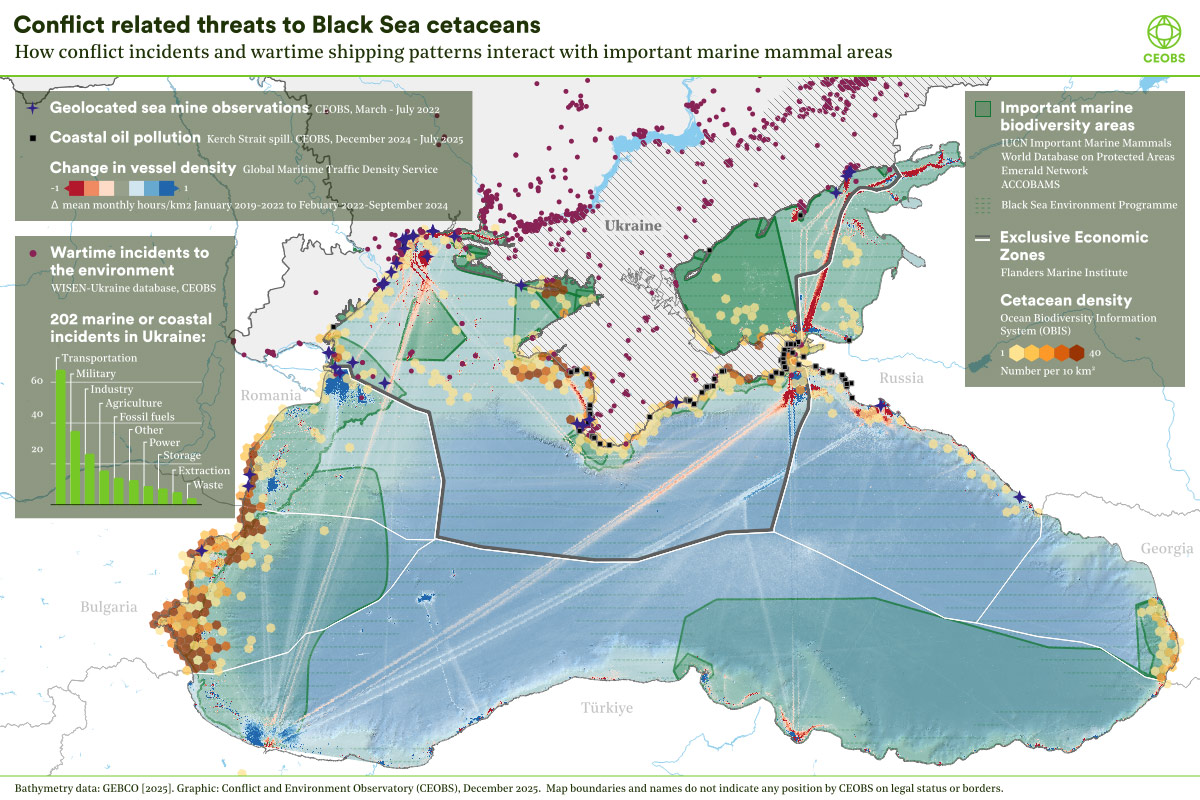

CEOBS’ WISEN Ukraine database contains around 200 incidents relevant to harm to cetaceans and to marine ecosystems, some of which could potentially inform ACCOBAMS’ research. The database, which is based on open-source intelligence and remote sensing, includes damage to military and industrial sites, and to ports and to merchant and naval shipping. We reviewed our database for incidents relevant to the marine environment, and here assess their potential implications for Black Sea cetaceans.

Black Sea life and death

The Black Sea is an enclosed marginal sea connecting to the Atlantic Ocean through the Mediterranean, via the Sea of Marmara. To the north, it connects to the Sea of Azov through the Kerch Strait. It receives substantial freshwater input from major rivers — the Kuban, Danube, Dnieper, and Don — while also taking saline Mediterranean water through the Bosporus. Below 150 metres, life is impossible due to the absence of oxygen and the presence of high concentrations of hydrogen sulphide and potentially nitrous oxide. With more than 80% of its volume hostile to life, the Black Sea contains the largest body of anoxic water on Earth, with life confined to the shallow oxygenated surface layer or to coastal areas.

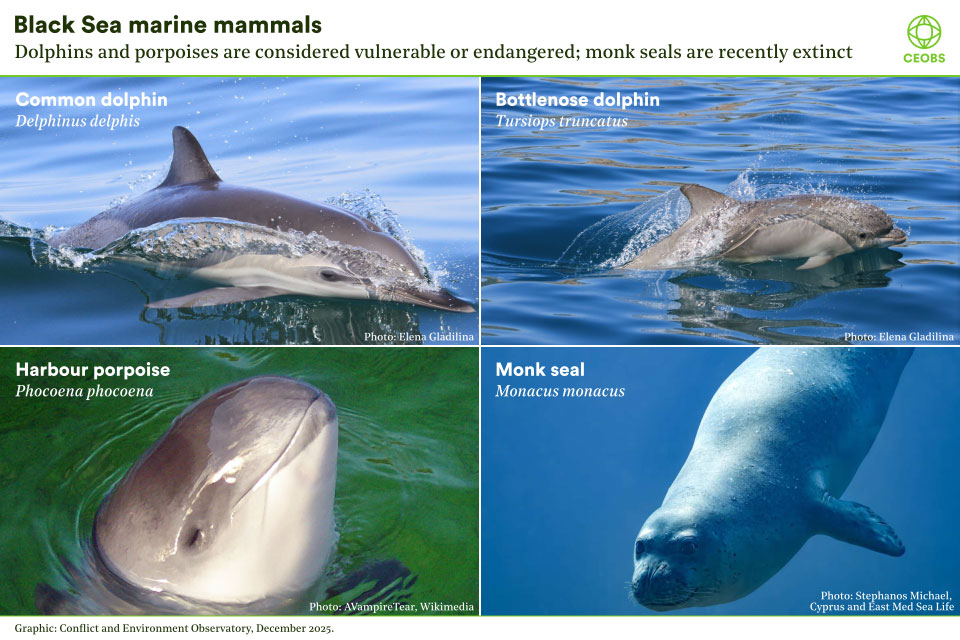

The Black Sea hosts three endemic, endangered and vulnerable cetacean subspecies: the bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus), the short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis), and the harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena). In addition, the region was once home to the Mediterranean monk seal (Monachus monachus), which is now extinct in the Black Sea. The Azov Sea harbour porpoise population is a distinct subpopulation from those inhabiting the western Black Sea. Cetaceans are widely distributed with sightings frequently recorded in the estuaries of major rivers and coastal lagoons. Beyond their ecosystem roles, the cetaceans are culturally and socially significant for people living around the Black Sea.

The historic hunting of Black Sea mammals for meat and blubber caused severe population declines and drove the monk seal to extinction within its Black Sea range, although a few individuals still survive in the Sea of Marmara. Since Türkiye banned cetacean hunting in 1983, key threats have included fishery pressures – chiefly overfishing of prey species and bycatch, as well as shipping, climate change, invasive species and pollution. Turbot bottom gillnets and trammel net fisheries, as well as illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (IUU), are responsible for the largest proportion of bycatch, and for the death of thousands of harbour porpoises. Climate-driven ocean warming is thought to be stressing Black Sea life; fewer cold water masses and increasing salinity are changing circulation patterns, with research needed to determine the implications.

The war as a new threat to cetaceans

In March 2022, dead cetaceans began washing up on Black Sea beaches. At first, these strandings didn’t seem unusual as similar events have been a recurring annual pattern; Spring strandings were traditionally linked to bycatch from fisheries. In such cases animals drown after becoming entangled in nets, and may have cuts or missing fins. However, at this time fishing activities were reduced, and the dead cetaceans bore injuries not typically associated with bycatch, indicating different causes of death that were perhaps linked to the war.

That year, cetacean mortality in the western Black Sea rose sharply. Researchers documented 914 deaths, including 125 on Ukraine’s Black Sea coast between February and December; most cases occurred before October 2022. Mortality was 2.2 times greater than it was between 2019-21, comprising: 59% harbour porpoises, 26% common dolphins and 10% bottlenose dolphins. The deaths and strandings attracted media attention, leading to the prosecutor’s office in Odesa launching an investigation. Remains were sent to Europe for independent post-mortem examination by marine mammal experts and, while the results have not been made public, the dominant hypothesis is that marine warfare was to blame.

The impact of marine warfare on cetaceans and wider marine ecosystems is poorly understood, and with tactics and risks rapidly evolving, even as marine ecosystems are under increasing pressure, it’s imperative that we work to understand these relationships. The rest of this post explores factors linked to the conflict that may have influenced cetacean populations in the Black Sea, and what should happen next.

Coastal and marine pollution

The Kakhovka Dam disaster was one of the most environmentally consequential incidents of the war, with substantial volumes of polluted floodwaters and sediment entering the Black Sea. Analyses of seawater and biological samples — fish, molluscs and cetaceans — detected toxic substances of both industrial origin (naphthalene, phenanthrene and anthracene) and agricultural use (β-HCH and heptachlor), along with elevated concentrations of heavy metals such as copper, zinc, chromium and nickel. Contaminants in grey mullet significantly exceeded EU maximum permissible concentrations, rendering their consumption hazardous to human health. Pollutants triggered extensive algal blooms and likely drove long-term, ecosystem-level impacts.

Many smaller scale incidents have also released pollutants into the Black Sea, these have included damage to wastewater treatment plants, to port infrastructure and grain terminals, and to coastal industrial sites like Azovstal in Mariupol, where intense damage added contaminants to extensive legacy pollution. At locations of intense fighting, such as Zmiinyi Island, which is surrounded by a marine protected area, hotspots of military pollutants may enter the sea through surface run-off or wind-blown resuspension. Coastal and offshore gas infrastructure presents another source of spills and pollution from combustion products, as do damaged vessels, like the Moldovan-flagged MV Millennial Spirit and the Russian landing ship Saratov. The emergence of the Russian “Shadow Fleet” has been an unintended consequence of Western sanctions, and two fleet support vessels have been involved in a substantial spill near the Kerch Strait that led to cetacean deaths.

Acoustic disturbance

Military sonar is believed to be a critical threat to cetaceans, and is thought to have been particularly prevalent in the early stages of the war, when the Russian navy sought to blockade Ukrainian ports. Today, it is anticipated to still be problematic around the Kerch Bridge and Russian-controlled areas. Both submarine and surface vessels employ sonar, and it is potentially harmful to dolphins, interfering with navigation and hunting, and damaging their inner ear and the hearing functions essential for survival. Dolphins show strong avoidance, changes in direction, and group configuration after hearing military sonar, which can impair feeding, and lead to strandings and death.

Munition detonations — whether at sea, in coastal storage sites, or aboard naval vessels — can also pose risks to cetaceans. The powerful underwater shockwaves from blasts can cause auditory damage, disorientation and even death. It is likely that hundreds of sea mines have been deployed in the Black and Azov seas, presenting an ongoing threat, while anti-personnel and vehicle mines have been laid on beaches, estuaries and wetlands — such as those of the Dnipro — to prevent amphibious invasion. Naval mines have been carried by the Black Sea’s counter clockwise currents to Bulgaria, Türkiye and Romania, where 94 have been destroyed through detonation in blasts that pose risks to cetaceans and other marine life.

Before the full-scale invasion, Ukraine had 18 deep-sea ports, and 11 river ports connected to the Black Sea. After losing safe access to a number of them, in 2023 shipping was moved to Ukrainian ports in the Danube Delta; an important cetacean habitat and listed by UNESCO and Ramsar. This move led to a 600 percent increase in maritime traffic in the delta, and larger ships entering it. Shipping traffic fell in 2024 when more vessels were able to use their former ports but ecologists remain concerned for the functioning of the delta ecosystem, which supports cetacean prey species and habitat areas. Maritime traffic carries with it a range of environmental risks. These include acoustic disturbance, chemical pollution from discharges or spills, channel erosion and the dispersal of invasive alien species.

Military infrastructure

The Kerch Strait separating Crimea and Russia is a hotspot for marine biodiversity. It’s an important marine habitat and migration corridor for harbour porpoise and bottlenose dolphins, and for their prey species, including gobies, anchovy and mullet during their Autumn and Spring migration. Russia’s construction of the 5 km Kerch Bridge began in 2016 after its seizure of Crimea and it has only grown in strategic and political significance since the start of the full-scale invasion.

The bridge has been the subject of repeated Ukrainian attacks, and Russia has heavily fortified the surrounding area, including with barges, piles driven into the seabed, and several lines of surface and underwater nets, all of which disrupt cetacean movement and migration. Repeated strikes by naval drones, vehicle-borne explosives and missiles, as well as Russia’s countermeasures, such as the controlled detonation of sea mines, the sinking of ferries and the construction of naval defences have all served to amplify the ecological risks. The activities generate intense acoustic pollution, raise the likelihood of toxic fuel spills, and fragment habitat, degrading the ecological integrity of the strait.

Fisheries

Pre-war, Türkiye was responsible for 61.9% of Black Sea fish landings by weight, followed by Georgia (19.9%), Russia (13.1%) and Ukraine (2.3%). Of the EU states, Bulgaria and Romania’s fleet alone comprised 1,345 vessels, 90% of which were small-scale vessels, landing 1.9% and 0.9% respectively. Historically, bycatch from fisheries has been a key threat to Black Sea cetaceans.

The war has had particularly detrimental impact on Ukraine’s fisheries, with the full-closure of commercial fishing, while in neighbouring Romania fishing activity near the Ukrainian border sharply declined. In contrast, fishers in Türkiye reported record-high catches of bonito anchovies and horse mackerel, and saw a substantial increase in their national turbot quota. While the disruption of fisheries in the northern Black Sea may have temporarily reduced pressure on cetaceans in that region, the resulting concentration of fishing effort in Turkish waters — especially in the turbot fishery — heightens the risk of negative fishery–cetacean interactions in that region. This shift underscores the need for enhanced monitoring of Türkiye’s fishing sector, and for proactive mitigation measures while the war continues and northern fisheries remain closed.

Next steps

The war has exposed Black Sea cetaceans to new stressors. These include physical harm from underwater shockwaves and sonar, exposure to an array of pollutants, as well as the consequences of habitat degradation. However, the war has also changed pre-existing patterns of human pressure on the Black Sea and its biodiversity, shifting shipping routes and fisheries, and modifying the day-to-day pollution discharges of the major rivers that feed it.

Untangling these complex relationships will be a priority for researchers, though one hampered by the paucity of data on the distribution and population of Black Sea cetaceans, and by access constraints while the war continues. Remotely documenting and characterising incidents that affect the marine environment can help, as can the post-mortem assessment of cetacean organs and tissues, which can reveal the type and concentration of pollutants, and their implications for health. Stakeholder engagement and citizen science could also provide useful insights if developed further. Above all, Ukrainian and regional experts need the financial resources to support these activities.

Independent investigation into the intensity and distribution of military sonar during the war remains challenging, meanwhile littoral states like Türkiye, Romania and Bulgaria — which in 2024 announced a joint plan to clear the Black Sea of drifting mines — could take steps now to work with experts to mitigate the impact of mine destruction on cetaceans.

ACCOBAMS has drawn attention to the conflict-linked threats facing Black Sea cetacean populations. Its recommendations should now encourage more detailed research, and the urgent evidence-based mitigation measures necessary to protect cetaceans, and the wider Black Sea ecosystem.

Dr Linas Svolkinas is a Researcher with CEOBS, Doug Weir contributed to this post. Our thanks to Dr. Pavel Gol’din Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology for his input on the text. If you find our work useful, please consider making a donation so that we can continue it.

- ACCOBAMS stands for the Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and contiguous Atlantic area. It is described as ‘a legal conservation tool based on cooperation’ whose purpose is to reduce threats to cetaceans, notably by improving current knowledge on these animals. It is underpinned by an intergovernmental agreement.