When faced with the human suffering of conflicts it can be difficult to think about their parallel impact on animals.

Wild and domesticated animals have long-suffered abuse, injury or death in armed conflicts. In this blog, Janice Cox and Jackson Zee explore this history of harm and the reasons behind it, arguing that the animal victims of war require greater recognition and protection.

Introduction

When the impact of armed conflicts on animals is considered, this is commonly subsumed by more general consideration of the “environment”, of “nature” or of “biodiversity”. These generalisations, of impacts on wildlife, and their habitats, can mask a deeper examination of precisely how conflicts, and military activities, harm animals.

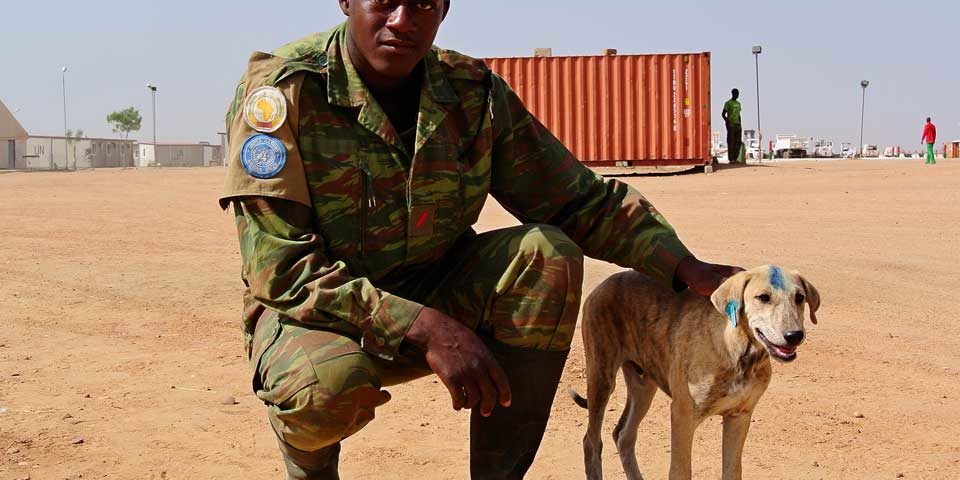

For example, consideration has been given to the best ways of rebuilding wildlife conservation after devastation by wars. And some attention has been given to animals in the context of UN peacekeeping operations. But there are numerous other ways in which animals are affected by armed conflicts and military activities. This blog explores this relationship, looking at wild terrestrial and marine animals, as well as domestic livestock, conscripted and companion animals.

Animals conscripted into war efforts

Prior to the mechanisation of warfare, armies often conscripted large numbers of animals into service to support their war efforts. Horses, donkeys, oxen, bullocks and elephants carried men, materiel and supplies; pigeons carried messages; camel-mounted troops have been employed in desert campaigns; and cavalry horses often led the charge on the front line.

It is thought that 16 million animals “served” in the First World War, the first industrialised conflict where huge numbers of animals were still in use. And between 1914-18 it has been estimated that 484,143 horses, mules, camels and bullocks were killed in British service alone. While the overall numbers of animals conscripted to directly support fighting has decreased over time, their use by militaries remains commonplace.

Dogs have been particularly widely used by the military, and remain so today. Their roles have included tracking, guarding, delivering messages, laying telegraph wires, detecting explosives and digging out bomb victims. Rats have also been used to detect mines, while dolphins and sealions continue to be trained to protect harbours from sea mines and divers. There are even reports of cats being used to hunt rats in trenches, canaries being used to detect poisonous gas and, in World War I, glow worms being used for illumination at night for reading communiques and maps.

These activities have often led to animal casualties and deaths, and the shocking death toll is covered below. But there were also untold deprivations and animal welfare issues, ranging from poor training methods, housing, overwork and exhaustion, exposure to heat or cold, starvation, thirst, disease and abandonment.

Animals have also been widely used in military research, particularly into weapons and injuries. Weapons have been tested for safety and efficacy, usually using pigs and sheep – many of which were shot and killed in testing. Rodents, rabbits and primates have also been used widely in laboratory testing in relation to the toxicity of weapon constituents, while still more animals have been used to test chemical, biological or radiological warfare, or for medical personnel to experiment on and train to deal with burns, blasts and wounds.

Animal victims of war

What follows briefly examines how wildlife, including marine mammals and fish, as well as farmed animals, working animals and companion animals can be affected by conflict.

Wildlife

Even low-level human conflict can drive dramatic wildlife declines. A study published in the journal Nature analysed data going back to 1946 to identify the effects of human conflict on large mammal populations in Africa. The results suggested that, of all the factors studied, repeated armed conflict had the biggest impact on wildlife – and even low-level conflict could cause profound declines in large herbivore populations. Weakened environmental governance has been shown to be a key factor in wildlife loss.

Wild animals can be killed and injured by landmines, while the increased availability of small arms can intensify unsustainable hunting. Wild animals are also hunted and killed for food, both as a coping strategy and for products to be sold to raise funds for the conflict. The extent to which non-state armed groups have used wildlife crime to raise funds is contested. Where the trade and consumption of wild meat is started during conflicts, it often continues into peacetime.

In the oceans, marine animals can suffer through naval exercises, with common pathologies being decompression sickness and acoustic traumas, and mass strandings of whales have resulted.

Zoos

Zoo animals are often the victims of conflict. In times of war, zoos lack paying visitors, and zoo animals are seen as a liability. The animals can be killed, eaten, injured, starved, stolen, traded, abused even abandoned or released into the conflict zones as a diversion to distract combatants and slow recovery efforts. Following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, in Baghdad, large carnivores like lions, panthers and jaguars were released from the Baghdad Zoo and from private residences by the retreating Iraqi forces in order to impede coalition forces from advancing on the city, these animals were ultimately killed, or captured then returned to the zoo in the weeks after the onset of conflict.

Livestock

Livestock have been injured in war, and specifically targeted and killed. The circumstances often mean that people cannot care for their animals, or feed them properly, and they can succumb to disease. In the chaos of war, animals can be eaten or over-worked. And shortages of veterinary care and veterinary medicines are common.

Working animals

Working animals are important for the transport of people, water, supplies and firewood. But, despite this, they are often slaughtered as food reserves have run out or sold because cash assets are needed and the provision of care and feed difficult. This places further pressure and vulnerabilities onto already struggling people, especially refugees and displaced people.

Companion animals

Companion animals can also be victims of war, being killed, maimed or abandoned. In times of extreme food shortages, they have been euthanised because owners could not feed them, or even eaten by their owners or other people in the community. In many cases, companion animals are abandoned and become lost in the chaos of war, especially when their owners are displaced or become refugees.

| The Animals in Conflict Timeline gives an overview of the impact of war on animals in conflicts over the past century. | |

|---|---|

| First World War 1914-18 | More than 16 million animals were made to serve on all sides, with nine million killed (including eight million horses, mules and donkeys). |

| Spanish Civil War 1936-39 | More than 16 million animals were made to serve on all sides, with nine million killed (including eight million horses, mules and donkeys). |

| Second World War 1939-45 | Over 750,000 domestic pets were killed in Britain in one week following a government public information campaign about their safety and expected food shortages. The German Army on the Eastern Front lost 179,000 horses in two months. |

| Vietnam War 1955-75 | Use of Agent Orange to eliminate forest cover destroyed the habitats of tigers, Asian elephants, gibbons, civets, leopards and other species. At least 40,000 animals were killed by unexploded landmines in the 20 years following the war. |

| Mozambique Civil War 1977-92 | Giraffe and elephant herds in the Gorongosa National Park shrank by 90 per cent. |

| Iran-Iraq War 1980-88 | Populations of wild goats, wolves, otters, pelicans, striped hyenas, river dolphins and other wildlife were wiped out or reached the point of extinction. |

| Sudanese Civil War 1983-2005 | South Sudan's elephant population fell from 100,000 to 5,000. |

| Afghan War 1990s | Over 75,000 animals were lost due to mines, more than half of the total livestock population. |

| Gulf War 1990-91 | More than 80 per cent of livestock in Kuwait died, including 790,000 sheep, 12,500 cows and 2,500 horses. About 85% of the animals in Kuwait International Zoo died. A deliberate oil leak into the Persian Gulf by Iraqi troops caused the deaths of up to 230,000 aquatic animals and birds. |

Animal protection organisations’ disaster relief work

A large number of animal protection organisations carry out disaster relief work to rescue, feed, treat and support animals displaced, harmed or threatened by war. However, very few have the resources to work on the underlying issues around policy and community resilience.

Indeed, researching this blog reminded me of one of my early missions after joining the animal protection movement. Working for the World Society for the Protection of Animals around 1991-2, I was dispatched – along with an experienced veterinarian, John Gripper – to assess the impact of the Croatian War on animal victims. We travelled with the Croatian Army and the Croatian Veterinary Services, who later published a report on the conflict: Animal victims of the Croatian war.

It was a truly shocking experience. In addition to the destruction of wildlife and habitats, there was deliberate targeting of farmed and companion animals. The veterinary services had advised farmers to place a blue – veterinary – cross on the roofs of their barns. What happened? These buildings were then specifically targeted, as economic sabotage. There were also massacres, where corpses were lined up alongside companion animals – with their throats cut.

Within the chaos of war, there were also many cases where those fleeing the conflict had missing companion animals, and some animal protection staff were caring for them, and trying to reunite with owners. They found that when this was possible, the reaction was overwhelming. Those who had lost family and friends, and possessions, were delighted to find their companions.

International law and policy towards animal protection

The concept of in situ protection is included in the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). It is not certain whether all multilateral environmental agreements continue to apply in times of armed conflict. However, “area-based” protection regimes, such as those included in the CBD and the UNESCO World Heritage Convention do require the continuation of “protected areas” in times of conflict.

Jérôme de Hemptinne’s study of Challenges Regarding the Protection of Animals During Warfare found that international humanitarian law (IHL) is deeply anthropocentric and largely ignores the protection of animals. For example, the Hague Conventions prohibit the destruction and seizure of an enemy’s property, but provide no definition of property. The question of whether animals qualify as “property” has been debated by animal law scholars. On one hand, this may give greater protection in war and conflict situations. But on the other, we would argue that the status of animals should be raised beyond that simply of property, given the fact that they are sentient beings. That said, some general IHL principles could potentially provide minimum safeguards to animals during armed conflict.

IHL does not contain explicit rules to mitigate the suffering of animals in armed conflict. However, the overall evolution of law’s approach to animals, notably its recognition of them as sentient beings, appears to allow for a progressive interpretation of IHL so as to constrain acts of violence against animals in war. The rules on the protection of civilian objects and on the environment, the proportionality principle, or the options for declaring demilitarised zones could all be activated to this end.

In connection to this, there have been a range of attempts to enhance the legal protection of animals and their habitats in relation to armed conflicts. In 1995, a Draft Convention on the Prohibition of Hostile Military Activities in Protected Areas was drafted by the International Council of Environmental Law and the Commission on Environmental Law of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Unfortunately, this failed to materialise into an international treaty but the principle of area-based designations to afford enhanced protection lives on through the work of the International Law Commission, and its ongoing study on the Protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts.

Elsewhere, the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 was modified to include a mention of animals, following advocacy by World Animal Protection. However, this was only in the context of “productive assets” – including livestock and working animals, as opposed to sentient beings deserving of protection in their own right.

Subsequently, in an update of the Rome Declaration by the European Regional Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction of the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction and the EU Disaster Mechanism, the Director General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations and the 28 member states highlighted the importance of addressing animals and animal welfare. This applies for all humanitarian actions within and outside the EU, and acknowledged that: “Actions to reduce the vulnerability of the population, economic activities, including critical infrastructure, animal welfare and wildlife, environmental and cultural resources such as biodiversity, forest ecosystem services and water resources, are of the utmost importance.”

International policy has a long way to go before the welfare, needs and interests of animals are properly recognised and protected in conflicts. Humanitarian organisations have been given a permanent mandate under international law to organise relief operations and undertake other humanitarian activities during armed conflicts. Animals also have a great need that is not yet recognised by the relevant international bodies. We argue that there is a pressing need to give international animal protection organisations a similar mandate to participate or intervene to organise relief and protection for animal victims of conflict.

Janice Cox has held a variety of management and advocacy roles in the international animal welfare movement over the past 30 years. She is now Policy Advisor for the World Federation for Animals, and is based in South Africa. Jackson Zee has over 25 years of experience in emergency management and humanitarian affairs working in sustainable development, animal welfare and conservation. He is currently Director of Disaster Relief for FOUR PAWS International, and is based in Austria.