Military exemptions are common in EU and national environmental regulations but the CBAM exemption may have unintended consequences.

Grace Alexander explains why exempting military products from the EU’s new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) undermines the bloc’s industrial decarbonisation goals and demonstrates a disconnect between its climate and defence policies.

What is CBAM?

The EU has positioned itself as a global leader on climate action and decarbonisation. Its European Green Deal sets a goal for carbon neutrality by 2050, while regulations such as the European Climate Law, the Industrial Emissions Directive and the Circular Economy Action Plan aim to reduce industrial emissions and minimise environmental impact across various sectors. Meanwhile its Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) aims to incentivise industries to reduce emissions and invest in low-carbon technologies.

The ETS is a carbon market that requires polluters to pay for their greenhouse gas emissions under a cap and trade system. The cap refers to the limit set on the total amount of emissions that can be emitted by installations and operators covered by ETS and is reduced annually in line with the EU’s climate target. A certain number of free allowances are distributed to prevent carbon leakage, whereby high emitting processes are relocated to countries with potentially weaker climate policies in place. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which came into force in January 2026, is a levy on emissions embedded in products imported into the EU. The CBAM aims to align carbon pricing between imported and domestically-produced goods in the EU market. CBAM will be progressively introduced at the same time as ETS free allowances are phased out, in order to reduce carbon leakage and encourage decarbonisation. Similar to the ETS, CBAM focuses on high-emitting sectors.

Carbon prices and the military

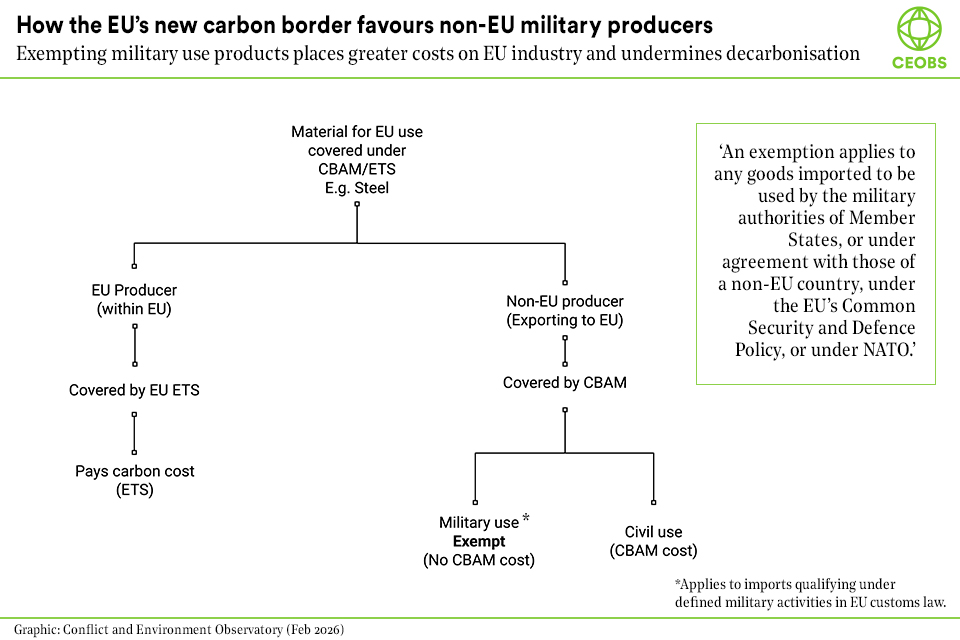

CBAM is designed to support decarbonisation and protect EU industry, however, it includes an exemption for goods imported for military use.1 This creates a situation where carbon-intensive materials used in military applications can avoid carbon pricing at the border, even as EU-based producers supplying the military sector with the same materials must pay for their emissions under the ETS. Moreover, an exemption reduces the pressure for decarbonisation on sectors in third-countries. The exemption raises questions on whether climate and defence policies are being aligned in practice, or whether the military carve-out will quietly undermine the EU’s own decarbonisation goals.

Many materials used in military applications are carbon intensive. For instance, iron and steel is fundamental to many military vehicles, infrastructure and munitions. The iron and steel sector is one of the highest emitting sectors, representing around 30% of total industrial emissions and around 8% of global emissions. To meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement, emissions from steel production need to decrease by 90% from 2020 levels by 2050. This requires the deep transformation of the sector and strong policy frameworks to support decarbonisation. Imports of steel represented 27% of total steel in the EU in 2024. Although steel used for military applications would be only a proportion of this figure, with rising military spending demand for materials also increases, and an exemption for military-use in this sector leaves a gap in decarbonisation potential.

Are EU industries at a disadvantage?

Industries within the EU would pay a carbon cost under the ETS, regardless of whether the product is for military use. Prior to the implementation of CBAM, some heavy polluting industries were given free allowances under the ETS in order to avoid disadvantaging EU producers, and industries exporting their emission-intensive processes to countries outside the EU. As CBAM comes into effect, these free allowances will be phased out in order to incentivise decarbonisation while also ensuring fair competition. However, with an exemption in CBAM for products and materials for military-use, EU military suppliers could be at a price disadvantage for supplying materials for military use, due to the cost of carbon under the ETS, while imports under CBAM of the same materials for military use would be able to avoid a carbon price.

Missed decarbonisation opportunity and material dependency

This exemption is at odds with both the EU’s aim for CBAM to ensure fair competition, and the aim to encourage the decarbonisation of high-emitting sectors. Moreover, this exemption results in a missed opportunity to promote military decarbonisation in a sector that is challenging to decarbonise. This is short-sighted as industrial policy is one of the most effective levers for adapting the sector to the transition. For other sectors, CBAM is expected to result in EU importers shifting to producers with lower emissions, while also incentivising industries to decarbonise, but the military sector will be excluded.

Imports of materials that are cheaper than EU-produced alternatives can undermine EU industry and create resource dependencies. Resource dependency entails a risk for the military due to supply security risks and unpredictable geopolitics. For instance, with growing military spending, European governments have seen a growing dependence on cheap steel produced outside the EU. Moreover, military-grade steel is only produced by a small number of companies, but these producers, some of which are in the EU, are already in a vulnerable position due to global competition. By exempting military imports from CBAM, the EU risks reinforcing price signals that disadvantage domestic producers, and potentially pushing military procurement into external supply chains, with higher levels of supply chain security risks.

Overall the military exemption under CBAM represents a missed opportunity to align EU climate and defence policies. By allowing carbon intensive imports for military uses to avoid carbon pricing, the exemption overlooks a lever to influence military decarbonisation. From chemicals and biodiversity, to greenhouse gas emissions, military exemptions are common in domestic and EU environmental policies and often go unchallenged. CBAM’s exemption, which is counterproductive to the EU’s collective security and climate interests, is a reminder that policymakers need to carefully consider the implications of military exemptions, and not add them by default.

Grace Alexander is CEOBS’ military and climate researcher. If you find our work useful, please consider a donation so that we can continue it.