Report: Investigating the environmental dimensions of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

Published: February, 2021 · Categories: Publications, Law and Policy

Summary

The recent fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh featured a range of environmental dimensions, both on the ground and in the virtual sphere. This report takes a neutral look into environmental damage during the 2020 fighting, and these wider environmental issues.

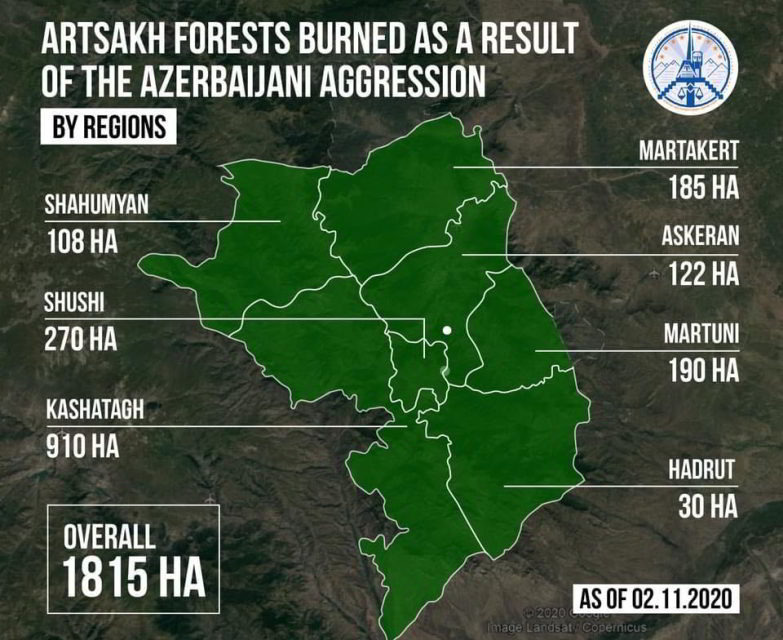

A prominent feature of the conflict were the fierce disinformation campaigns fought online. In this highly partisan space, the scale of unevidenced environmental propaganda was unprecedented but fit seamlessly with a long history of absolutist narratives. Posts predominantly referenced the forest fires via incendiary weapons, but water, deforestation, landscape, environmental warfare, and agriculture also featured. Posts from pro-Armenian actors were directed by civil society, whereas pro-Azeri content and strategy emanated from government sources and was significantly amplified by Turkish social media accounts.

Using earth observation data, we investigated the hundreds of landscape fires that occurred between 26th October – 4th November, primarily in forests. The fires were climatologically anomalous, so likely arose directly from the fighting. The balance of intentional to accidental burns remains unknown. We also present new evidence of urban fires, but further work to assess their scope is required.

Some of the landscape fires were likely caused by incendiary weapons. Building on existing open source investigations, earth observation data confirms that one of the events was associated with the explosion of an Armenian field munitions store. We review the legal aspects on the use of these munitions, as their utility in clearing vegetation to aid drone warfare may represent an emerging tactic.

Pre-conflict, Azerbaijan was in the midst of a water crisis, and control of Nagorno-Karabakh’s rich water resources may have been viewed as a benefit from any confrontation. Water infrastructure was targeted during fighting, with some resources transferring hands. However, many pre-existing issues remain unresolved, such as maintenance of the Sarsang reservoir. The cooperation required to find solutions remains distant – depoliticisation of the environment is required.

The recent, historical and frozen conditions of the conflict have significantly impacted the landscape and geodiversity. This is clearest along the line of contact, which is now strewn with unexploded ordnance, trenches, conflict debris and toxic remnants of war – a threat to people, livelihoods and biodiversity. Proper clearance, testing and remediation will be required to make these lands safe. There also remains the risk of future environmental damage from militarised corridors, new lines of contact, industrial facilities such as the Sotk gold mine, and resource extraction.

CEOBS’ motivation

Our entry point into the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was via the environmental disinformation on social media. However, whilst researching this, two concerns became apparent – firstly, the range of environmental issues at play, often interconnected but not considered at a high-level, and secondly the poorly informed and partisan way these have been investigated and reported upon. This report is by no means complete, but is a politically unbiased starting point to raise and counter these concerns.

Contents

1. Conflict context

Before proceeding into the report, it may be useful for those unfamiliar with the conflict to have a basic primer of the commonly accepted history.1 However, it must be noted that much of the discourse is contested, with differing and sometimes controversial readings of the history of the disputed area.

During the 19th century, Nagorno-Karabakh was part of the Russian empire, where the Christian Armenian and Muslim Turkic who had inhabited the area for centuries lived in relative peace. Following WW1 and the collapse of the Russian empire, the area was claimed by both of the newly independent nations. Although it was inhabited mainly by Armenians, it fell under Azerbaijan’s borders. The situation was complicated by the presence of the British mission in the South Caucasus. Tensions were resolved to an extent with the arrival of the Bolsheviks in 1920. Nonetheless, it took the USSR until 1923 to determine that administration of the autonomous region would be by the Azerbaijani and not Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Following the collapse of the USSR and independence for Azerbaijan and Armenia in 1991, building ethnic clashes escalated into a war between Armenian secessionists and Azeri troops. The fighting lasted until 1994 when a Russian-brokered ceasefire was signed, leaving Nagorno-Karabakh – and bordering areas of Azeri territory – under Armenian control. Deaths were estimated at between 20,000 and 30,000, with more than one million Azeris fleeing the region. The scars from this war are still visible in the landscape, via hundreds of abandoned settlements, or the line of contact, a barren and pitted strip between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan. In 1992 the Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh declared its independence and has since administered the region, although the state has never been internationally recognised.

To help encourage peace, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) established the Minsk Group, chaired by France, Russia and the United States. With the exception of the 2016 ‘four-day war’, the conflict remained relatively ‘frozen’ with only low-intensity fighting until the outbreak of the latest conflict on 27th September 2020. The fighting lasted 6 weeks, with Azeri forces taking much of the territory in Nagorno-Karabakh, before a Russian-brokered truce entered force on 10th November. It is estimated that nearly 150 civilians and more than 5,000 soldiers were killed, with a further 130,000 people displaced – predominantly residents of Nagorno-Karabakh fleeing to Armenia. Alongside the ground war, the conflict has been characterised by an intense information war, played out on social media (primarily Twitter), and with particular reference to the environment.

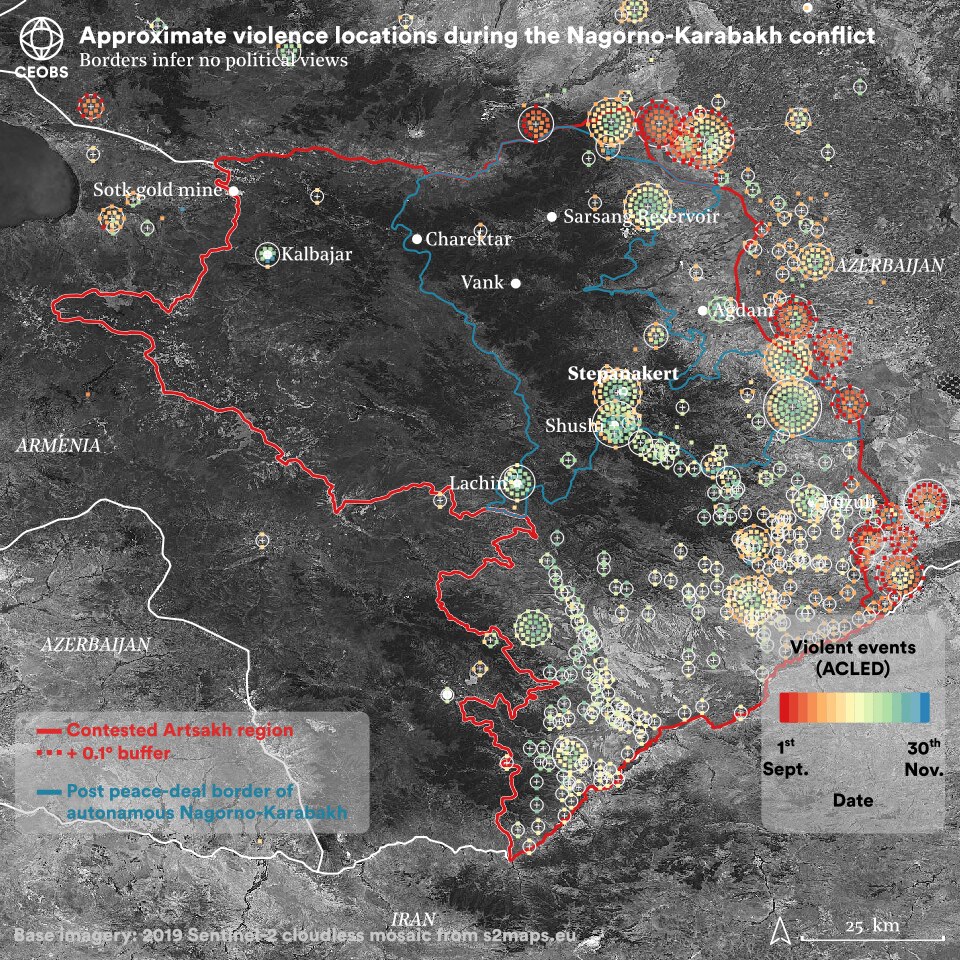

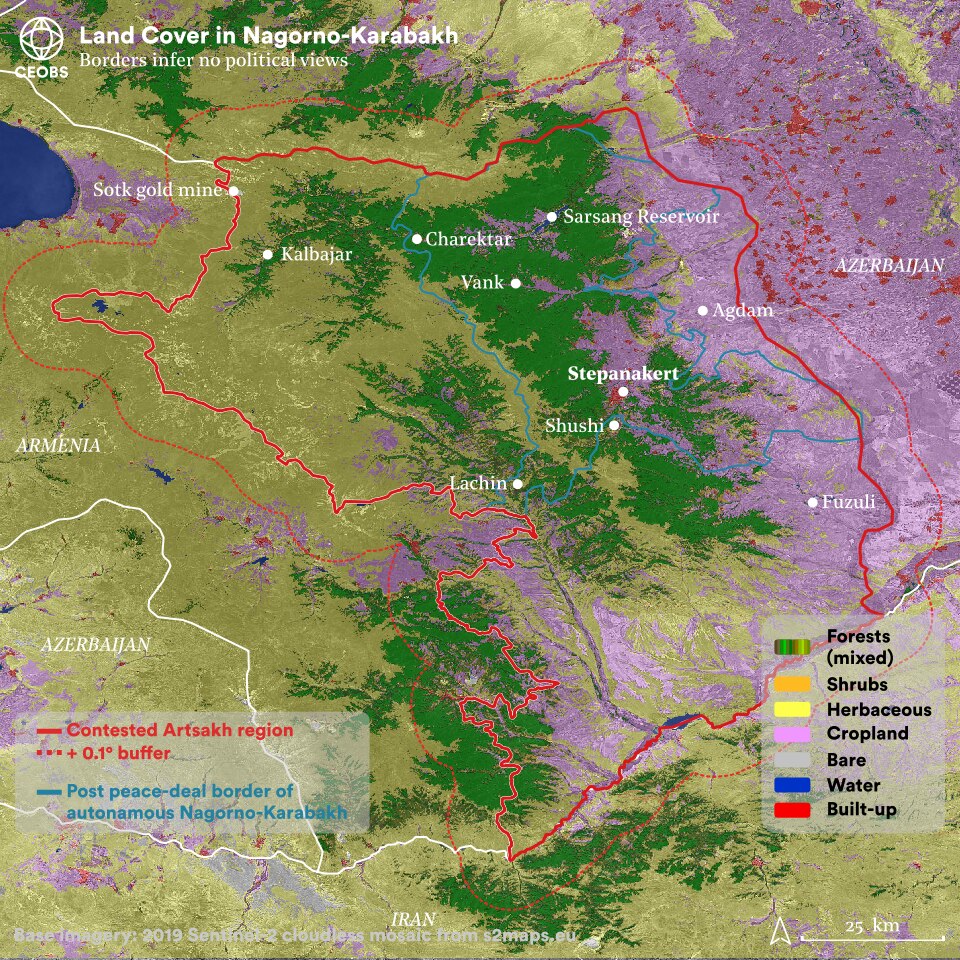

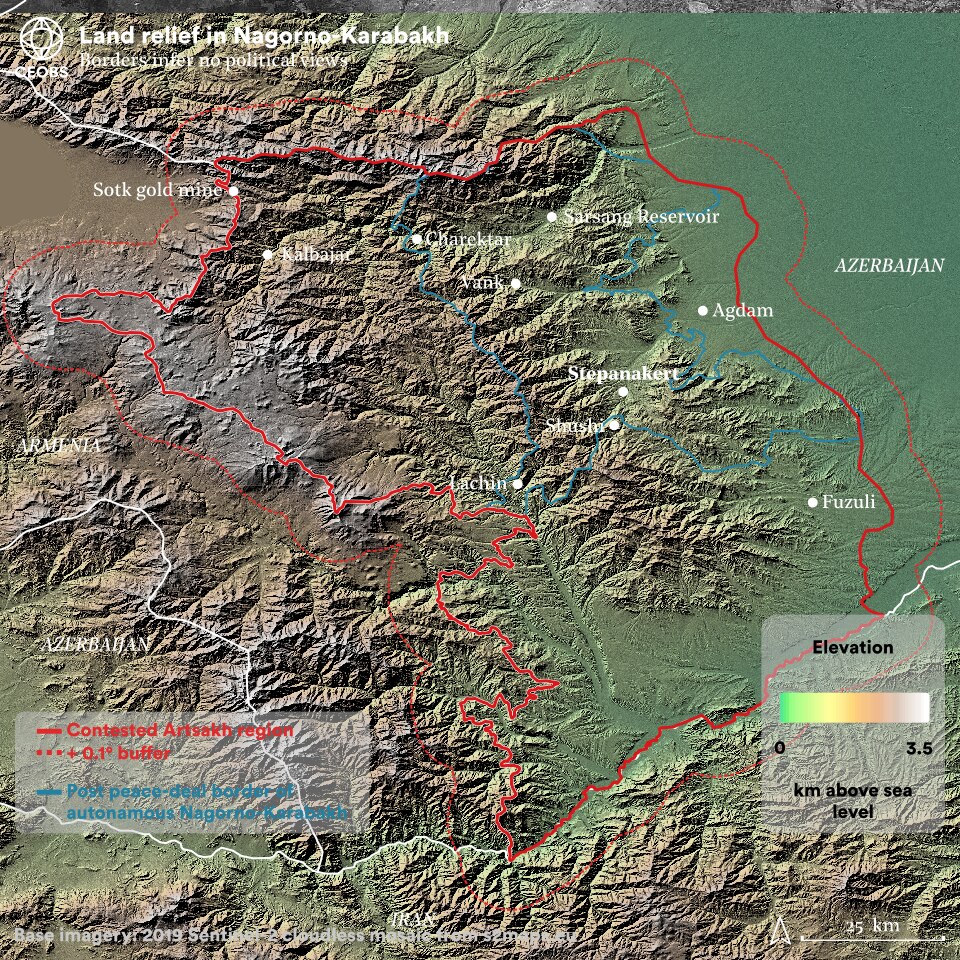

Figure 1. Geographical, conflict and landscape context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Click arrows to view different figures. Data sources (1) Base imagery: Sentinel-2 cloudless (https://s2maps.eu) by EOX IT Services GmbH (Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2019). (2) Land Use: Copernicus Global Land Service: Land Cover 100m: Collection 3: epoch 2019: Globe (Version V3.0.1), © Copernicus Service Information 2021. (3) Armed violence data from the publicly available Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). Note, events are located to the nearest settlement with varying levels of precision, so mostly do not provide the exact location an event occurred. (4) Digital elevation model: NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mission V3 Product, processed with Google Earth Engine. (5) Border data from Open Street Map.

The name of the region and conflict itself is somewhat contested and politicised.2 Throughout this report we refer to it as Nagorno-Karabakh, following established convention.3

As is to be expected, the borders marked on maps can be contentions and are challenging to acquire from neutral sources. For simplicity, just to indicate the main areas of fighting, for graphics in this report we have used the borders of the Artsakh region from Open Street Map. This decision does not reflect CEOBS’ political views.

2. Environmental propaganda

One unusual feature of the recent conflict was the extent to which the environment featured in the discourse, with the term ecocide co-opted and weaponised by both parties. We begin the report with a review of the environmental propaganda associated with the conflict, as it frames much of the discourse and will likely continue to do so.

Prior to the conflict, such polarised social media and fake news could have been predicted as just a very 2020 way of expressing entrenched and absolutists narratives of victimhood from this frozen conflict. This was aided by both militaries uploading daily combat footage to proclaim victories, and the lack of objective and neutral journalists on the ground. This deluge of information reflected one extreme of conflicts in the 21st century, whilst the near-concurrent conflict in Tigray, Ethiopia reflected the opposite extreme – there was an information black out.

As context, Azerbaijan is the twelfth worst ranking country in the 2020 Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index,4 and the Ministry of Foreign affairs actively encouraged journalists to avoid the conflict. Hence, much of the journalistic content originated from official sources, and was intended to garner international support.

However, the extent to which the environment was used as one of the central motifs in this information war was perhaps surprising, even in spite of the trend towards weaponising environmental information in conflicts. The claim and counter-claims surrounding fires, as reported below, provides an insight into the environmental information war, but the scope was much wider. Nonetheless, although there were some environmental dimensions before, it wasn’t until after the iconic imagery of fires and incendiary weapons emerged that competing narratives about total environmental destruction took hold. Both conflict parties had different approaches to the spread of this environmental propaganda.

War crimes and ecocide by Azerbaijan and Turkey must be stopped immediately and punished to fullest extent of Int’l law. #ArtsakhStrong #StopAzerbaijaniAggression #StopAliyev #StopErdogan #environment #Ecocide #EnvironmentalJustice @UNEP @Greenpeace https://t.co/qNZ3CqPqyj

— AGBU (@agbu) November 5, 2020

🇦🇲Armenian vandals cut down trees in the forests of🇦🇿Kalbajar. Why is the world watching the collapse of the ecosystem? #stopecoterror #StopArmenianEcoTerrorism #KarabakhisAzebaijan @EcologyWA @the_ecologist @hrw @NikolPashinyan @BBCWorld @CNN @nytimes @HikmetHajiyev @CNBC pic.twitter.com/uJaUtu588o

— 𝐓𝐔𝐑𝐀𝐋 ✪ (@mr_tural_) November 18, 2020

Extremely important!!

With means of remote targeting #Azerbaijan has started attacking the civil infrastructures, which can also trigger an environmental disaster.— Artsrun Hovhannisyan (@arcrunmod) October 3, 2020

Armenia continues to commit a crime agst humanity & heritage of #Azerbaijan as well as agst the ecosystem of the whole Caucasus.

While all🌍fights against climate change & catastrophes which aren't in the far future,🇦🇲makes its own "contribution".#StopArmenianEcoTerrorism @UNEP pic.twitter.com/6aaUM793gW— Azerbaijan at UNESCO (@AzDelUnesco) November 26, 2020

ECOCIDE ALERT 🚨

Azerbaijani forces, along with the support of Turkey and trained mercenaries are committing an ecocide on one of the world’s biodiverse forests in Artsakh / Արցախ & the greater Qarabaq region by dropping phosphorus munitions. 1/ pic.twitter.com/Hm0V4KTm9q— haso քուրօ #FreeArmenianPOWs 🌹🌍 (@kooyrig) November 3, 2020

The ecosystem in #Lachin is threatened as Armenians intentionally burn down the houses and damage infrastructure.#Ecocide#EcoTerrorism#StopArmenianEcoTerrorism#StopArmenianAggression#StopArmenianVandalism#KarabakhisAzerbaijan pic.twitter.com/9WrEHGVH3J

— Orkhan (@_OAslanov) November 26, 2020

On 27 of September Azerbaijan and Turkey started large scale war against people of Karabakh/Artsakh, factually perpetrating new Genocide, which now is accompanied by Ecocide. The forests of Artsakh are under the fire after Azeris use phosphorus missiles .#StopErdogan #StopAliyev pic.twitter.com/lmq3AKNSEC

— Ashot Ghoulyan (@Ghoulyan) November 2, 2020

Killing their own animals while leaving Lachin on 30 December is not a good idea.

It's better to take them with you rather than taking toilets.

And I am sure these animals are better than you🇦🇲 on end 🙄 pic.twitter.com/A5QZyYlivo

— Tahseen Khan✍🏻 (@BalochKhan3) November 29, 2020

All #Azerbaijan expects @UNDP is the same standard applied to all. #StopArmenianVandalism #StopArmenianEcoTerrorism #NagornoKarabakh pic.twitter.com/GsS6Bd3vNe

— Karabakh Information Centre (@KarabakhIC) November 19, 2020

#Forests in #Artsakh on #fire due to #Azerbaijan's use of white #phosphorus munitions; #Armenia applies to int'l organizations#StopAzerbaijaniAggression #Stepanakert #Shushi #StopErdogan #Ecocide #genocide https://t.co/RMYoJGwNQ6 pic.twitter.com/dvWsSvQu95

— Tehmine (@Tehmmina) November 7, 2020

The Armenian Environmental Front has released a joint statement signed by 50 institutions expressing concern over environmental damage in Nagorno-Karabakh. They accused Azerbaijan of using white phosphorus on forested areas.

⚡️ Live updates: https://t.co/34Z6CjL6Cm pic.twitter.com/lk01lvw5kx

— OC Media (@OCMediaorg) November 3, 2020

These #Armenians who must leave Azerbaijani lands that they occupied 30 years ago, cutting and taking the trees with them too😶 @Greenpeace#ArmenianWarCrimes #StopArmenianEcoTerrorism pic.twitter.com/xc2KdNetw9

— Sa Ra (@SaRaa_isr) November 18, 2020

Figure 2. Carousel of environmental information war tweets. Use arrows to scroll through.

Approach by pro-Armenian actors

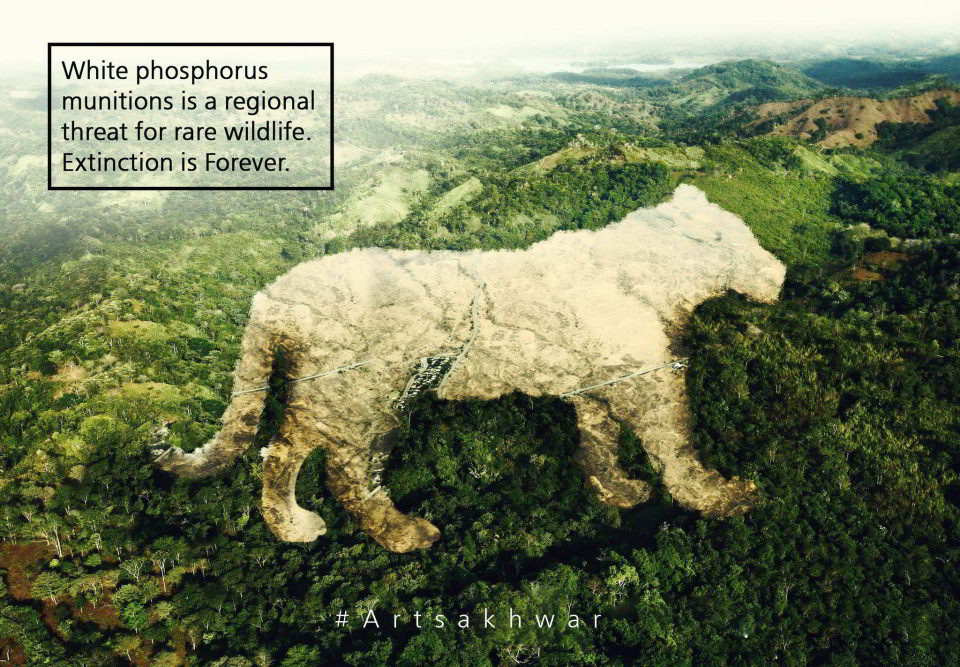

Civil society organisations were most prominent in directing pro-Armenian environmental information online. A key moment came on the 2nd November when a group of 51 NGOs signed an ‘Ecocide Alert’. The alert was headed up by the Foundation for the Preservation of Wildlife and Cultural Assets (FPWC), and included signatories from small environmental NGOs based mainly in Armenia, but also in France, Sweden and Luxembourg. The alert highlighted the significant biodiversity and number of endangered species in Nagorno-Karabakh, noted how the use of white phosphorous posed an existential threat to their survival, and called on action from global environmental actors to prevent ‘ecocide’.

Significantly, the language used was not very partisan and blame for the use of white phosphorous was not attributed to either party. However, we note that the text of the alert differed significantly on some of the websites of the signatories– for example, the Transparency International Anticorruption Center are far more vocal in blaming Azerbaijan, and made reference to other alleged war crimes.

This duality of approach was also present in the visual content generated as part of the ecocide alert (Figure 3). The FPWC produced four memes to accompany the alert, all using emotionally striking nature imagery and with the same tag line – “White phosphorus munitions is a death sentence. Extinction is Forever. #Artsakhwar”. However, the most commonly shared meme – and one used by other signatories to the alert – appears very similar but with a more partisan tag line – “Prevent Ecocide in Artsakh. Azerbaijani military forces reportedly used white phosphorus munitions in Artsakh forests”. The meme also features a more arresting image – of a Persian leopard in the flames of war – and the nuance in the style suggests it originates from a different designer.

Following on from their statement, the Armenian NGOs sought support from international counterparts to help increase the pressure.5 However, it seems there was little response from these organisations, most likely because of the evidence deficit and partisan nature of some of the postings – ultimately resulting in a negative outcome for the environment.

Approach by pro-Azerbaijan actors

In contrast to the civil society-led approach, the environmental messaging from the Azerbaijani side seemed to be more government driven. In particular the Azerbaijani Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources were important actors. They produced a series of memes that were widely circulated on social media (Figure 4), including by many official accounts, such as Azerbaijan’s delegation to UNESCO, or their embassy in Canada. The ministry also prepared press releases and held a roundtable event “Environmental Terrorism of Armenia against Azerbaijan”, which aimed to “inform the international community about the environmental crimes committed” and which coincided with the UN’s #EnvConflictDay on November 6th.

Indeed, whilst there was much environmental propaganda via domestic channels, the Azeri approach also involved targeting international publications. For example, ecocide is the focus of one of the many paid-for articles in the EURACTI, a legitimate network aiming to inform EU policy. The author of the piece is a political scientist, not an environmental expert, and one based at a state-funded thinktank – the ‘Center for International Relations Analysis’, established by presidential degree in 2019. The piece focuses on what they term ‘the environmental terror historically perpetuated by Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh’, but provide no robust scientific evidence. Notably there is no mention of the implications of the fires and incendiary weapons, despite being published well after the circulation of imagery, nor any other environmental impacts of the recent fighting.

Intriguingly we have found this article has then been referenced as an opinion piece, i.e. not promoted content, in an article lambasting the response of the international community to the so-called Armenian ecocide. However, the conflictandwarreport.com website hosting this article is deeply suspicious. Although professional looking, it was only registered October 27th 2020 and the non-Azeri content on the website is simply copied and pasted from other media outlets – it is possible this is to give the outlet the air of legitimacy and independence, such that unsuspecting visitors are inclined to believe the highly partisan reporting on Nagorno-Karabakh. Likewise, the original EURACTIV article also links to other suspicious websites, for example thelondonpost.net, which gives the impression of an established UK publication (it is not), and has a surfeit of stories on Central Asia with a pro-Turkey and pro-Azerbaijan line. It appears there is an ecosystem of fake news sites playing off each other in an attempt to control the international narrative.

Anecdotally from our research, it seems there are more environment-related posts on Twitter by those backing Azerbaijan. This would be consistent with a recent analysis that indicates there were more than twice the number of pro-Azerbaijan hashtags compared to pro-Armenian. In part this may be due to the greater number of social media users in Azerbaijan,6 but social media access was reportedly blocked; instead, it seems that traffic from Turkish accounts was particularly important. Research by Teyit, a Turkish fact-checking not-for-profit social enterprise, found that the false information was spread online in eight languages, but overwhelmingly in Turkish and Azerbaijani.

There were specialised hashtags coined by those affiliated with Azerbaijan, such as #StopArmenianEcoTerrorism, #StopArmenianEcocide or #StopArmenianEcocrimes, although often these had little to do with the natural environment. Comparatively there was no dedicated hashtag for the Armenians, with posts mostly tagged under the catch-all #StopAzerbaijaniAggression. The practise of “astroturfing” – a small number of coordinated accounts churning out prolific volumes of content to create an illusion of broad support – may also have played its part, given indications from early on in the fighting, and evidence from previous tensions in July 2020. During the conflict, Facebook also took action on a large network of fake activity connected to the Azeri state.

Figure 4. Environmental information war memes circulated on social media by pro-Azerbaijan actors. Use arrows to scroll through. Source: The memes were produced by the Azerbaijani Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of the Republic of Azerbaijan, i.e. an official government source and, somewhat bizarrely, they are sponsored by a career growth competition in Azerbaijan (Yukselish). They can be found across social media, for example here.

In popular culture

The environmental dimensions of the conflict even entered popular western culture via the unlikely route of the hugely popular heavy metal band System of a Down. Based in the USA, they are comprised of Armenian diaspora and the conflict prompted them to compose their first new song in 15 years called ‘Protect the Land’. The song is a pro Artsakh anthem with the themes of environment and landscape as cultural heritage at the core, its lyrics include: “What do we deserve before we end the earth”. The video for the song features fire as a central motive, and in press releases the lead singer emphasised how Azeris had “set their forests and endangered wildlife ablaze using white phosphorus, another banned weapon”. The song has had nearly 10 million views on YouTube, and more than 12 million streams on Spotify. It was reported on in music publications across the world (e.g. the NME here in the UK), and gained publicity via possibly the most famous celebrity of Armenian descent, Kim Kardashian. As such, the song – and its message – has likely reached a very different audience to traditional media.

On the other hand, analysis by the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab indicates that Turkish popular culture, in particular the K-pop community, was mobilised to spread a pro-Azerbaijani message in another sign of the attempt to control the international narrative.

Common amongst social media posts from both sides was the tagging of large environmental organisations and figureheads, in particular Greenpeace, Greta Thunberg and Leonardo DiCaprio. In some instances, the aim will have been cynical, to amplify and legitimise their sides’ narrative, however in many cases these interactions will have been out of a genuine sense of care and desperation for the environment. After the fighting, there has been some dissatisfaction expressed at their lack of response or concern.

Review

The disinformation situation is complex and only briefly touched upon here. With both sides seemingly partaking in the ‘shadow war’, it is deserving of further analysis by social media experts and we encourage such studies to include how environmental disinformation was used.

Given the precedent that has now been set, it is possible that environmental (dis)information will remain a soft weapon to try to assert narratives from both parties. There is already evidence of this since the cessation of fighting, particularly on the Azeri side. One recent TikTok post, watched by more than 650,000 people and widely shared on Twitter, allegedly shows Armenians burning beehives as they fled Nagorno-Karabakh, whilst there are other allegations of river pollution from molybdenum mining in Armenia. Both are reprehensible but as no evidence or exact location is provided in either case, they are impossible to verify and difficult to investigate further – it is expected this will be a recurring theme.

While environmental claims and counterclaims often occur in conflicts, the scale of the environmental information war for the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and its widespread coverage on social media was unusual. It appears to have been sparked by the tangible and undeniable scenes of forest fires and incendiary weapons. We note that following the peak in environmental-related tweets the number of fires declined, and there were no further allegations of incendiary weapons use. Was this in some way associated with the environmental information war and pressure exerted on both parties, the result of traditional diplomatic pressure, or merely a strategic military choice? In whichever case, given the success of environmental (mis)information as a propaganda weapon, it seems likely that its use may continue to increase, especially where partisan green nationalism may be bolstered by climate change. If this is the case, it may well make tracking and verifying environmental harm in conflicts more difficult.

3. Fire

Landscape fires

During and after the conflict, both sides have accused each other of using fire as a weapon through the use of incendiary munitions, for example to remove tree cover. Using earth observations, we can gain a better understanding of the frequency, type and scale of landscape fires through the detection of active fires and burned areas.

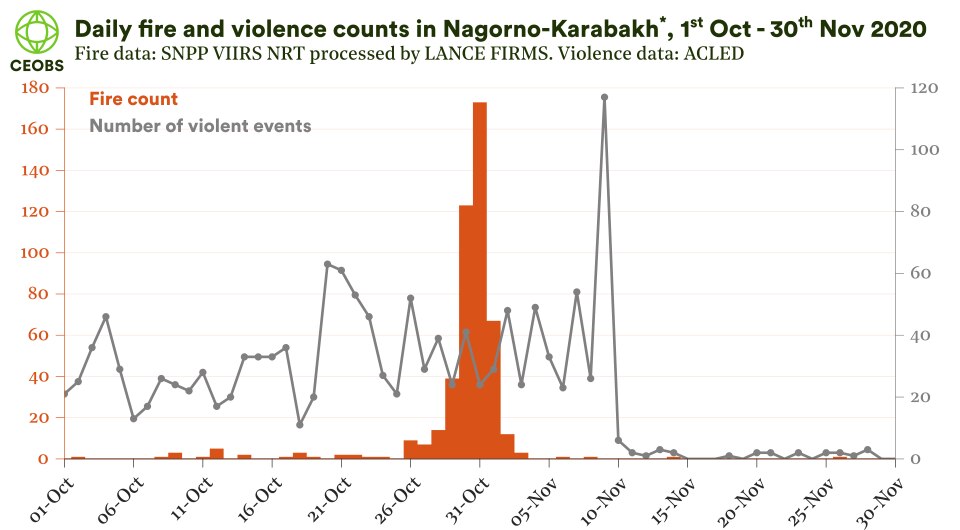

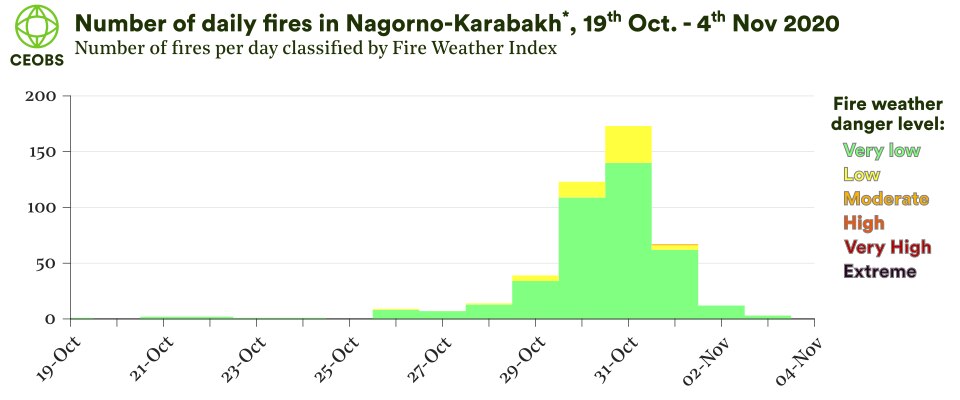

Figure 5. Number of fires per day during October and November 2020. Fire data: Suomi NPP Near Real-Time, processed by the Land, Atmosphere Near real-time Capability for EOS (LANCE) Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) from NASA. Violence data: The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1.

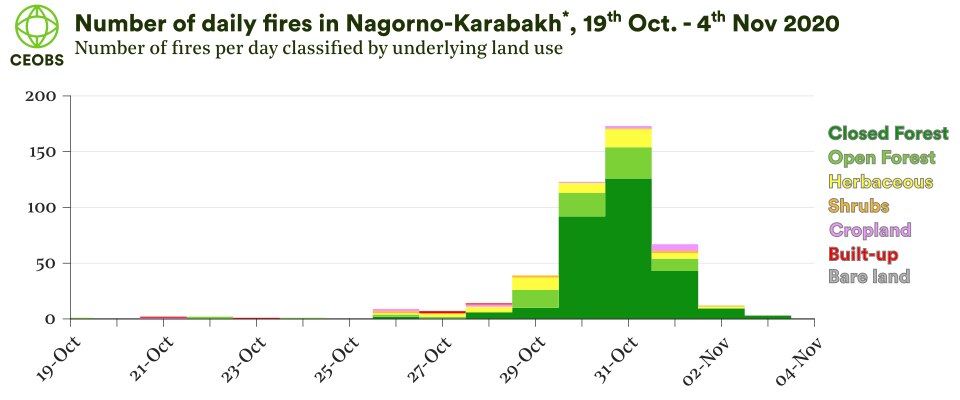

Figure 5 shows a timeline of the daily number of fires as detected by the Suomi-NPP VIIRS instrument. There is a clear pulse of fires between the 26th October and the 4th November, peaking on the 31st of October. Either side of this there are very few fires detected. Over this pulse period 447 fires were detected by the Suomi NPP VIIRS instrument.

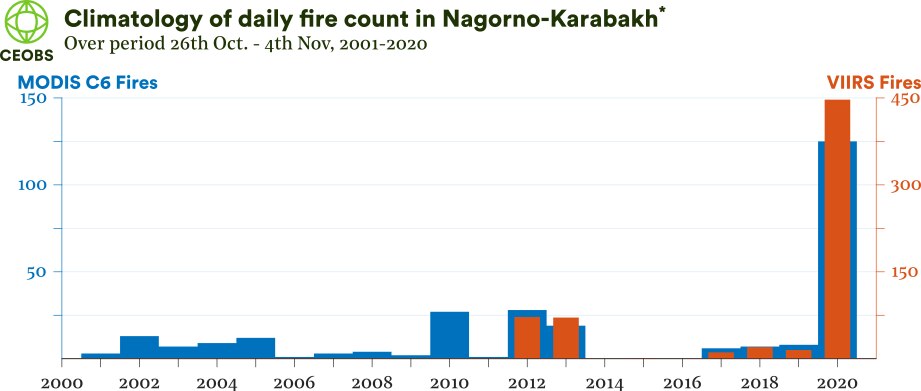

Figure 6. Time-series of the number of landscape fires detected over the 26th October to 4th November period. MODIS C6 data is available 2001-2020 and thus provides a longer time-series, whereas VIIRS data is available since 2012 and can detect more fires because of its superior spatial resolution. n.b. MODIS and VIIRS data from 2020 is the Near Real-Time data as standard quality data was not available at the time of writing. *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1.

The previous maximum was just was 72 in 2012, the year the instrument was launched, and indeed the sum of fires between 2012-2019 is only 203 – half the number recorded in 2020. The same story is true when inspecting the longer records from the MODIS instrument. However, the environmental conditions are unlikely to have been equivalent for this 9-day period time-period in the preceding years. To try to account for this bias, we established the maximum fire count in other 9-day periods over October and November. Although most of these maximum counts were way below 2020 levels, between 7 – 15th Nov 2010 there were more fires than 26th Oct – 4th Nov 2020 (177 vs 145). Taking a closer look however, these fires were located close together to the south of Kalbajar – in contrast to the geographically dispersed nature of fires in 2020. All together, these climatological analyses indicate that the 2020 fire activity was anomalous.

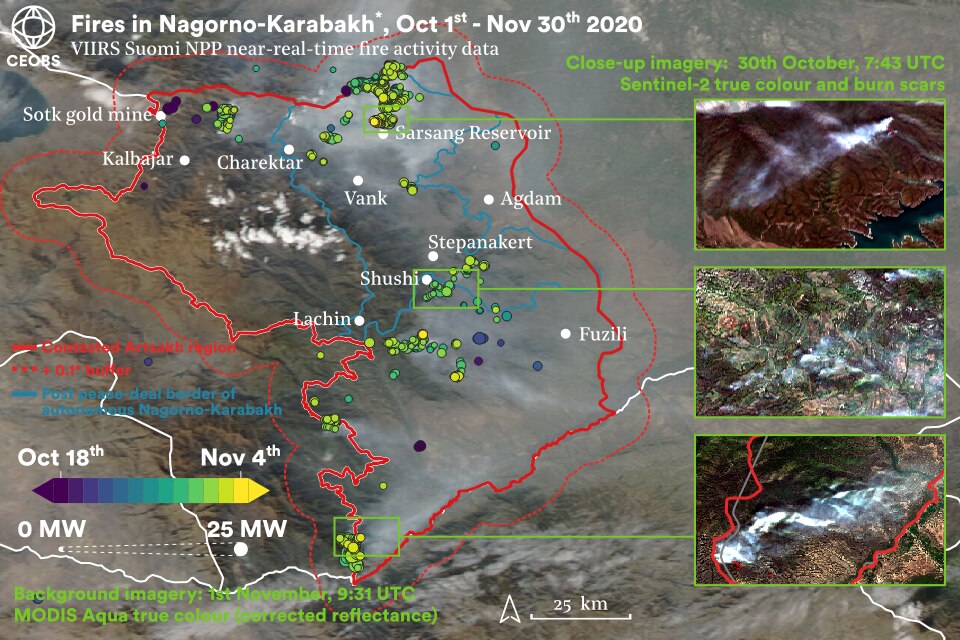

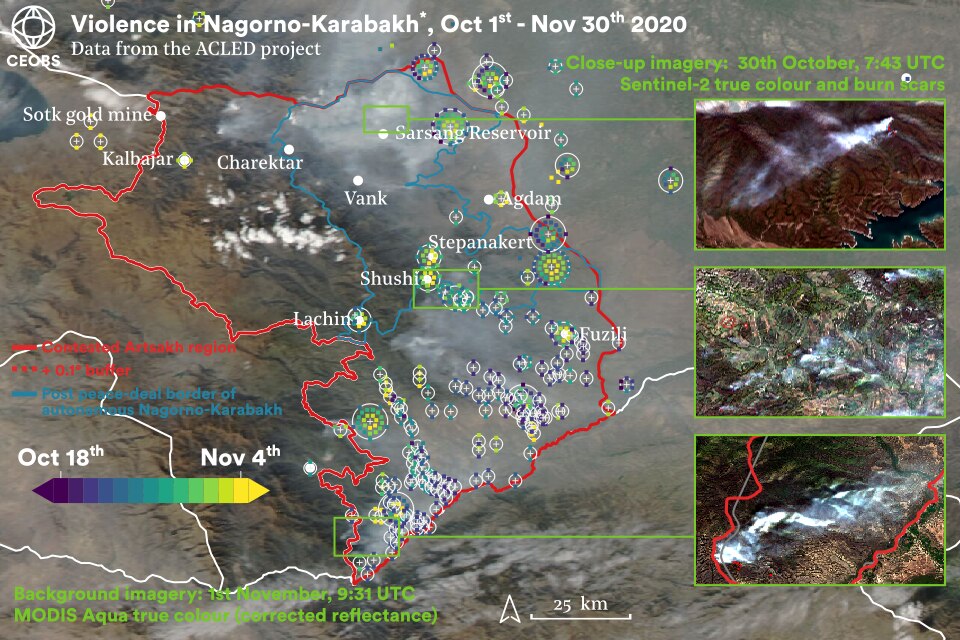

Figure 7. Spatial distribution of fires and armed violence October 18th to November 4th 2020. Markers are coloured by date. Fire markers are sized by a proxy for fire intensity, fire radiative power. Fire Data: Suomi NPP Near Real-Time, processed by the Land, Atmosphere Near real-time Capability for EOS (LANCE) Fire Information for Resource Management System (FIRMS) from NASA. Violence data: The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1.

The locations of the fires are displayed in Figure 7 and it can be seen that there are clusters of fires around the border of Artsakh, to the south-west and north, in the interior near the Lachin corridor and around the main urban centres of Shushi and Stepanakert. The total has been calculated from independent measurements, as is illustrated in Figure 8. The methodology we employ here estimates the total area of high or moderately-high burned land as 102 km2. 7

Figure 8. Map of high severity or moderate-high severity burned areas based on the differenced normalised burn ratio approach. Process uses Sentinel-2 cloud and snow masked mosaics for pre-fire (between 17th September and 20th October) and post-fire (28th October – 10th November). Processed in Google Earth Engine using code adapted from that made publicly available by the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs (UN-SPIDER). *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1.

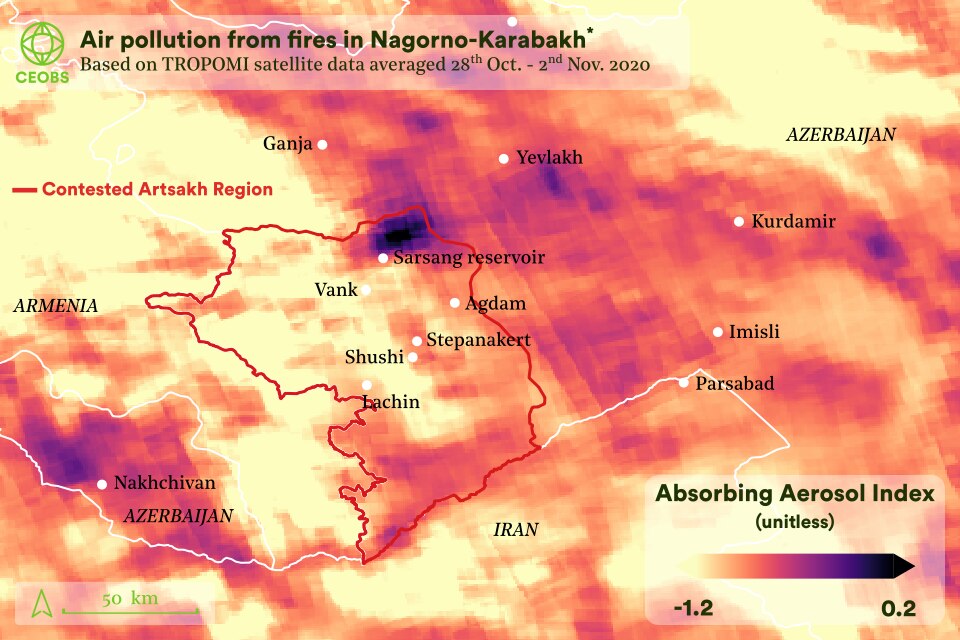

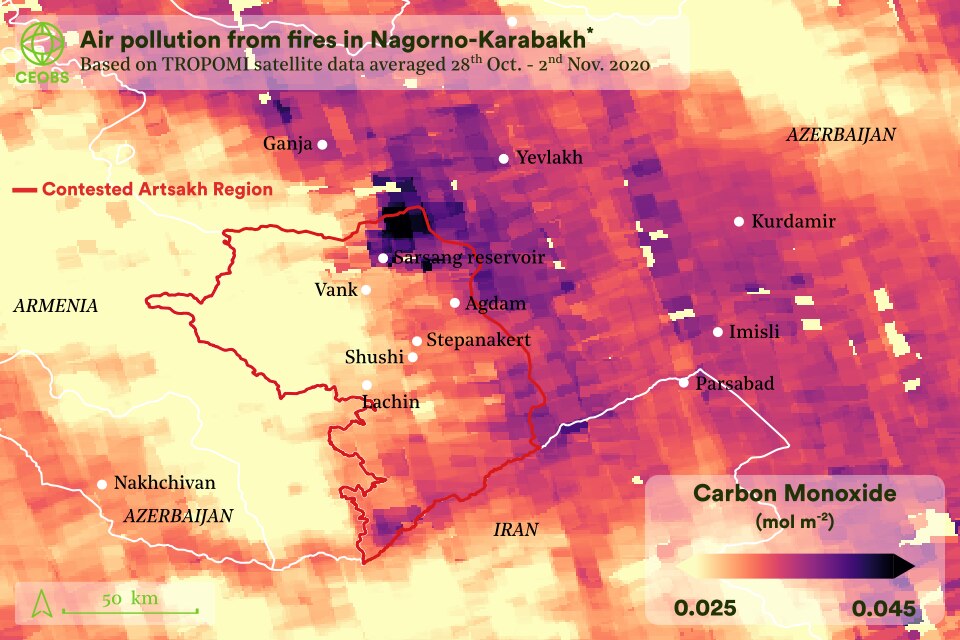

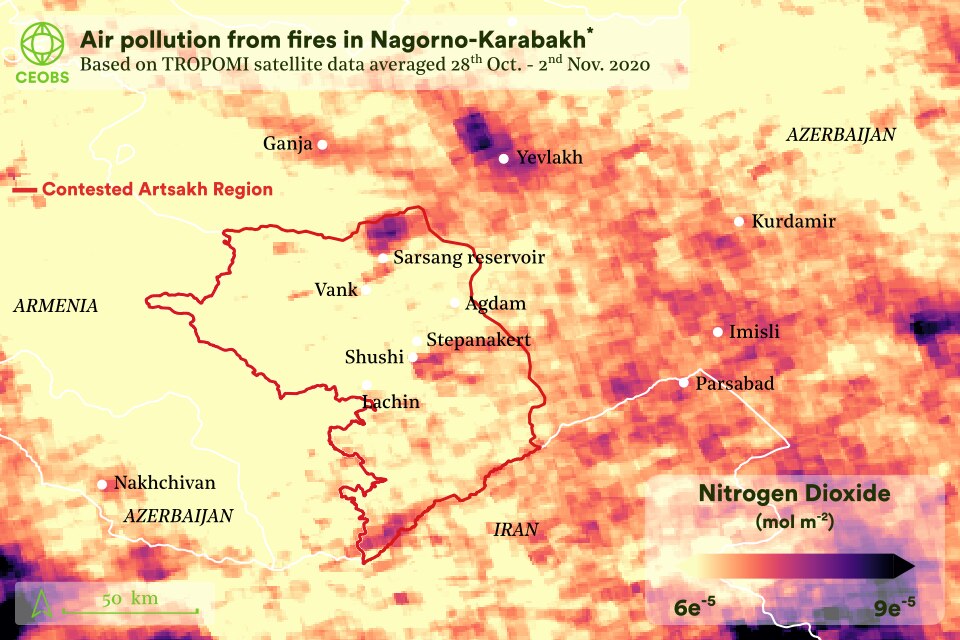

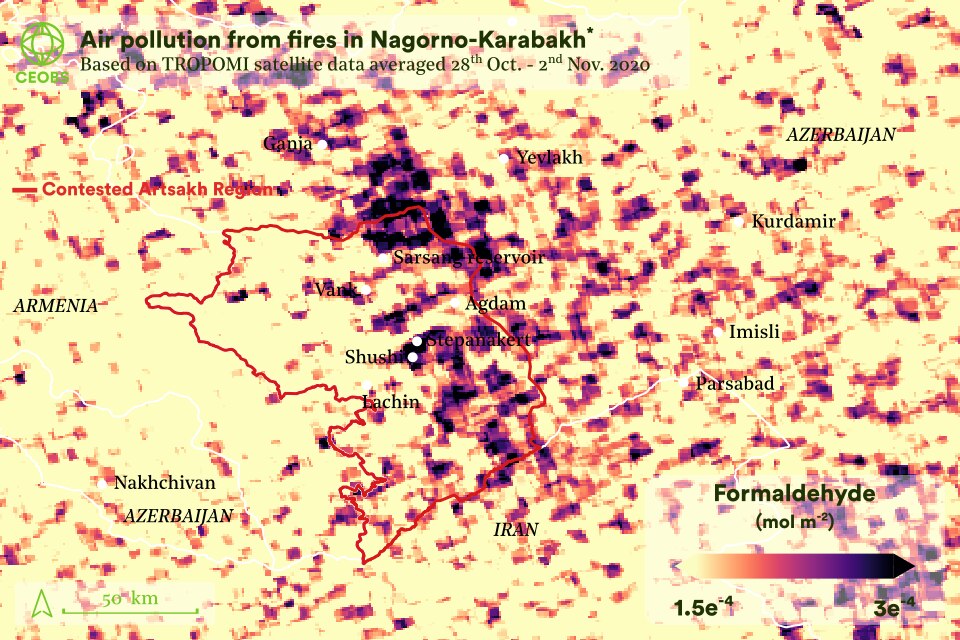

Figure 7 also shows that significant volumes of smoke were generated from the fires, and combined into a regional haze that travelled easterly and north-easterly into Azerbaijan on the prevailing winds. Satellite measurements of air quality by the TROPOMI platform in Figure 9 show that this regional plume had enhanced levels of carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, methane and absorbing aerosol (black carbon). Close to the fires, high concentrations of formaldehyde were measured. In both the near and far field it is likely that these air pollutants from the fires caused acute health problems for vulnerable groups.

There may have been significant impacts for biodiversity, both from the immediate impact of the fires but also over the longer term due to the damage sustained to habitats, including contamination from toxic remnants of war. Forest resources also support local livelihoods and so their loss may be significant for civilians in the area, especially in concert with other impacts of the conflict.

Figure 9. Air pollution from the fires (and local point sources) as viewed from space via the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI instrument. Use the arrows to click through concentration maps of the absorbing aerosol index, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and formaldehyde. *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1

The question arising is to what extent the anomalous fire activity was linked to climatic conditions or to the conflict – and if so, how? From the fire data alone, we can infer that the conflict has played a role – the fire clusters and burned areas correspond to the main areas of fighting and, notably, there is only one fire visible outside the Artsakh area in the same period. Furthermore, by coupling the fire data to a land use map we can conclude that the fires occurred primarily on closed forests (Figure 10).8 This is consistent with the theory of removing forest cover for military advantage, especially for an aerial advantage. It is notable that some fires also burned on cropland, which was possibly collateral damage.

Figure 10. Daily fire count in each land use category 19th October – 4th November 2020. *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1.

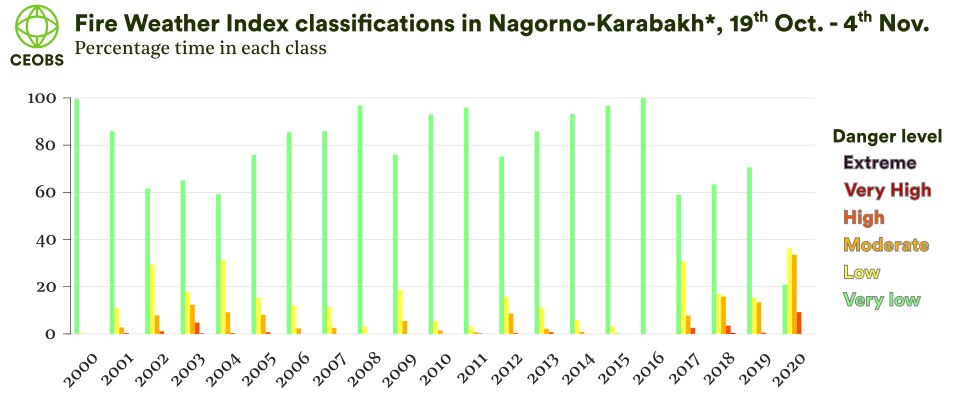

However, to fully discount a significant role of climate and meteorology in the fires a more robust analysis is required. To do this we investigated the Fire Weather Index (FWI), a unitless index used to estimate the danger of fire ignition, spread and intensity due to meteorological conditions, such as wind speed and behaviour, temperature, humidity and fuel moisture. If FWI values were higher during the recent fires then it is possible that the burns were more the result of a conducive climate, with the fighting just providing the initial, unintentional ignition source.

Compared to all previous years there was clearly more significant fire weather in 2020, with 43% of pixels having a moderate or high fire weather index. This is likely associated with higher than average temperatures for eastern Europe and the Caucuses. This October was the warmest on record. However, some caution is advised in interpreting the fire weather climatology as the data for 2020 comes from a different source, one based on forecast data, compared to 2000-20, which is based on reanalysis data.

Figure 11. Classification of fire weather index classifications over 19th October – 4th November 2000-2020. The 2000-2019 data is from Copernicus Emergency Management Service, based on meteorological data from the ECMWF ERA5 reanalysis dataset, with a spatial resolution of 0.25-deg. The 2020 data is from the European Forest Fire Information System (EFFIS) platform, based on forecast meteorological data from the ECMWF at 8km spatial resolution. *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in Figure 1.

Nonetheless, these results may lead one to conclude that the fires were primarily the result of favourable conditions. However, diving deeper shows this to not actually be the case – the majority of fires occurred on pixels with a low fire weather danger, as seen in Figure 12. The locations of fires and high fire weather were spatially anti-correlated. Put simply, the high fire activity was not due to the raised fire weather. This finding is a strong indicator which, together with the additional evidence, leads us to conclude that the anomalously high number of landscape fires was primarily caused by military activity. The obvious follow-on question is this – which military activities? We investigate the widely claimed use of white phosphorous in Section 4.

Figure 12. Daily fire count in fire weather index classification 19th October – 4th November 2020. *The region used for Nagorno-Karabakh here is the borders of the Artsakh region plus a 0.1-degree buffer, as indicated in figure 1.

Fires in the built environment

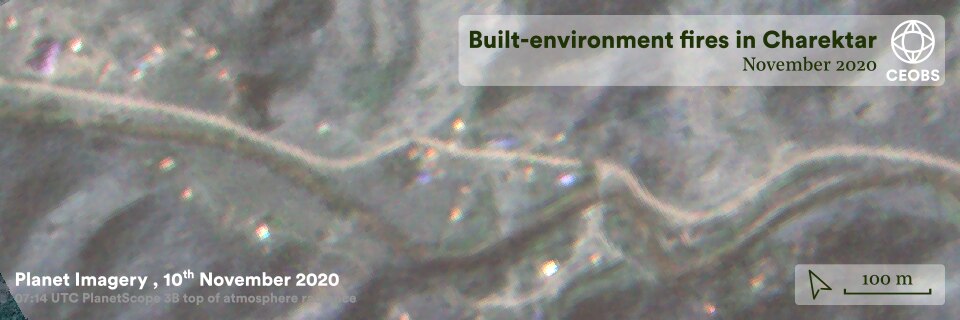

In addition to landscape fires, there is evidence from the BBC, Bloomberg and AFP of damage to the built environment from intentional fires lit by Armenians as they abandoned the Kalbajar and Lachin areas. On social media, the narrative from partisan Azeri accounts was that this practise was widespread – this take was reported on and spread internationally by the Associated Press/Yahoo!News. However, given the scale of disinformation during the conflict, this claim needs further testing and evidencing. Open source investigators on Twitter have georeferenced five of the burning houses in Dadivank and Kelbajar, where the smoke was also visible from moderate resolution satellite imagery. Information from earth observation is useful only to a limited extent. Unfortunately building-scale fires are typically too small to detect and, in any case, the period of these alleged burns was moderately cloudy so detections may have been missed. However, high resolution imagery can be used to determine the state of buildings in locations where these burns are alleged.

In its reporting, the Guardian names the village of Charektar as having at least 10 house fires on Friday 13th November, but without providing direct evidence. Figure 12 shows high resolution satellite imagery that indicates damage to at least eight buildings in the village. A visual inspection of the area before and after the alleged burning suggests that the red roofs characteristic of buildings in the area have disappeared. However, care is required with this type of visual analysis because of the different instruments used and environmental conditions the images were taken under. Instead, we have been able to confirm the destruction more robustly by analysing the radiances of the images: we computed the difference between dates and took the average across the red, green and blue bands. This highlights the locations of significant reduction in radiances, which line up with the houses. It is reasonable to assume that this damage is the result of fires, although we cannot say this with total confidence, let alone identify the perpetrators or their motives – a limit of remote sensing.

Recently, there have been counter-claims from partisan Armenian accounts that the Azerbaijan military were burning abandoned Armenian houses. In all cases, as more openly available very high-resolution data becomes available, for example through Google Earth, the exact scale of these fires in the built environment may be easier to determine, and will likely be the focus of future work.

Figure 13. High resolution satellite imagery indicating damage to the built environment from fires in Charektar village, Nagorno-Karabakh. Click arrows to view different imagery.

There were also similar partisan accusations on both traditional and social media that Armenians were intentionally felling trees before fleeing – part of an informal scorched earth policy. These were generally supported by three pieces of evidence. The first is an unextraordinary image of 30-40 tree stumps along an embankment, but with fresh growth visible – so clearly cut some time before the recent fighting, as per the images original description. Nonetheless, most posts accompanying this image have the narrative of recent felling. The second piece of evidence is a video near Kalbajar showing small-scale logging by a roadside, but there is little to indicate this is not ordinary behaviour or is ill-intentioned. The final evidence is that of a sole Armenian man chopping down a handful of trees beside his house, admitting it is an act of sabotage.9 Together this evidence is not strong enough to support claims of widespread mass deforestation by fleeing Armenians, despite the volume and ferocity of such claims on social media. Furthermore, our earth observation analyses suggest no evidence of large-scale vegetation clearances unconnected to landscape fires – a further example of weaponising environmental disinformation.

4. Use of incendiary weapons

There is video and hospital injury evidence of the use of incendiary weapons during the fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh. Both parties to the conflict blamed each other. Evidencing the events and responsible parties is important because of the significant impacts on people and the environment.

Incendiary weapons ignite upon contact with oxygen and are intended to set fires and cause burns, produce thick smoke during the daytime and light up an area at night. Incendiary weapons inflict serious internal and external burning, whilst the smoke can be toxic. The munitions can also harm the environment through fires and bioaccumulation in water, soils, crops and animals – which may later be consumed by humans.

It is still not clear if the weaponry used in Nagorno-Karabakh was white phosphorous or thermite. Reasons posited for the use of the incendiary weapons included to burn down the forest, either to remove cover from ground troops or to cause ‘ecocide’, or to harm civilians hiding in the woods. Armenia claims the attacks started on the early morning of the 27th September, intensified at the end of October as the fighting moved to forested and mountainous terrain, and that civilians were hit. The Azeris claim that the Armenians were using white phosphorous to create a smokescreen to hinder the drones that controlled the airspace above Nagorno-Karabakh. We note that there was significantly more volume on social and traditional media from pro-Armenian affiliates surrounding these attacks.

This is not the first time there has been a blame game surrounding incendiary weapons. During the 2016 fighting, Azerbaijan accused Armenia of firing white phosphorus into its territory, near the village of Tartar. The Armenians rejected this report, saying the accusation was fabricated. Azeris also pointed to a shell containing white phosphorous found in their territory, near the town of Fuzuli, on 8th October as evidence of Armenian use of incendiary weapons. No open source evidence has been available to verify this claim. Nonetheless, the Azeris pointedly disposed of this shell in front of international cameras.

Stills from the key videos alleging use of incendiary weapons are presented in Figure 14, alongside the earliest publication dates and conflict party reporting.10 Differentiating between the types of incendiary munition is difficult and requires expert analysis, for example in investigating the burst angles, and hence we do not have the capacity to do so in this work. Nonetheless, the primary ways to identify incendiary weapons is via the cascade of trajectories of bright white light, caused by their pyrophoric nature, and the thick smoke they produce. Videos A and C certainly appear to fulfil this criterion, and video B to a lesser extent.

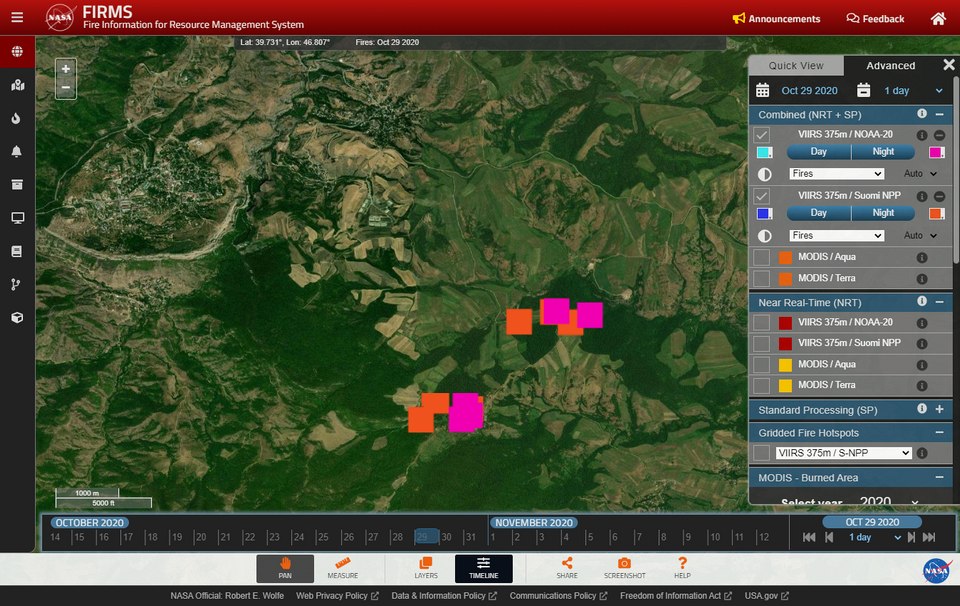

We currently have the most information on the incident in video B – based on the similarity of plume shapes and the nearby landscape, it seems likely to be the result of an explosion at an improvised Armenian field ammunition depot, following a drone strike by Azeri forces as shown in videos D, E and F (Figure 15). Footage has emerged of ammunition lining roads in the region, with trees used as cover; perhaps providing a motive to remove tree cover. This particular strike happened on the night of the 29th October and has been georeferenced to a woody hill approximately 2km away from the village of Signax, south-west of Sushi. The appearance of the fire and plume is quite different to that of video A and C, and indeed more characteristic of a large explosion of many munitions, including incendiary weapons.

#Armenia: "Azerbaijan used White Phosphorus"#Azerbaijan: "Armenia used White Phosphorus"

Both lied.

The video with the White Phosphorus shows the explosion of an #ARMENIAN (!) ammunition depot destroyed during the night of 29 October.

It's the same smoke plumes. pic.twitter.com/hZZ4Hc5YQQ

— Thomas C. Theiner (@noclador) October 31, 2020

The claim of Azerbaijan forces using WC is fake.The explosion that took place was in an ammunition depot of Armenian forces , meaning the white phosphorus belongs to Armenian forces and was next to the village of Signax.Proof through geolocation.

3rd image by @ghost_watcher1 pic.twitter.com/rTGsdWx2QX

— CaucasusWarReport (@Caucasuswar) October 31, 2020

Figure 16. Tweets from open source investigators identifying Signax as the location of both videos B and F.

Satellite fire data in Figure 17 indicates there were no fires at this location during the daytime of the 29th, but there were during the night-time overpass at approximately 20:30 (NOAA-20 VIIRS) and 21:30 (Suomi NPP VIIRS). The following morning at 07:43 a Sentinel-2 overpass illustrated a fire and smoke still visible at this location – see Figure 19. Other fires can be seen burning nearby in this scene with causes unknown. Nonetheless, together this earth observation evidence helps further corroborate that video B is of an ammunition explosion.

Figure 17. Screenshot from the NASA FIRMS platform showing fire activity on the 29th October 2020.

Figure 18. Screenshot from the EO Browser by Sinergise Ltd of Sentinel-2 imagery, from overpass at 7:43 AM on 30th October 2020. Smoke is visible and the burned area identified by red/orange following use of the wildfire visualisation script by Piere Markuse. Signax fire and smoke denoted by green box.

Unfortunately, there is limited information on the incidents shown in videos A and C. For all the brilliant work by open source investigators on video B, there is none on A and C – perhaps reflecting their objective but partisan positions. This raises a general point on the need for careful consideration by neutral actors when using information from partisan open source investigators in active conflicts, and in particular establishing what is not reported on.

There have been efforts at open source investigations from Armenian actors, in particular from the Fact Investigation Platform but they do not present any compelling evidence on the locations, timings, nor responsibility. The same is true of a widely shared piece by the usually thorough Digital Forensic Research Lab of the Atlantic Council. Meanwhile, a recent Amnesty report into unlawful strikes during the conflict made no mention of incendiary weapons.

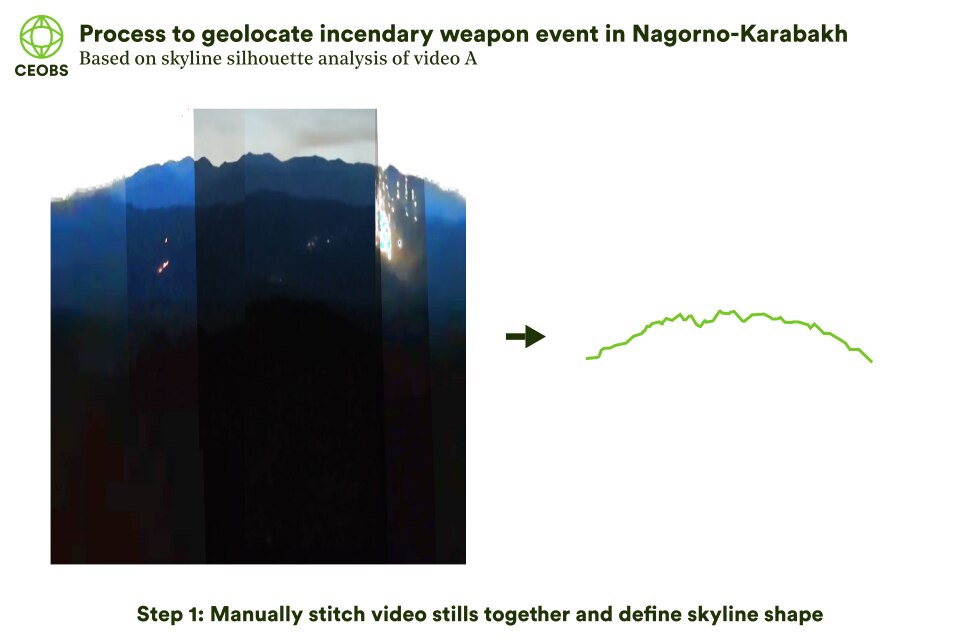

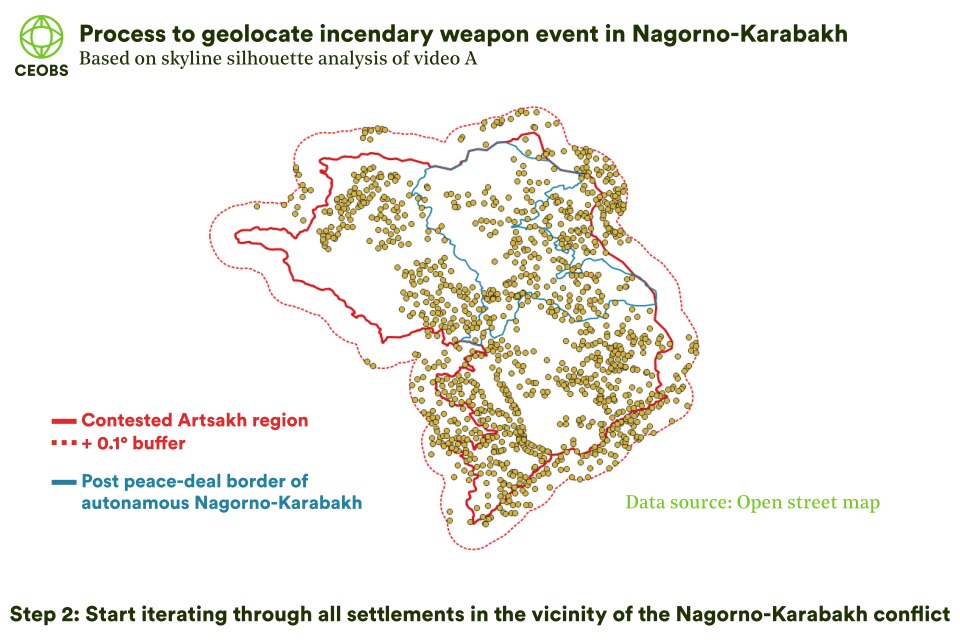

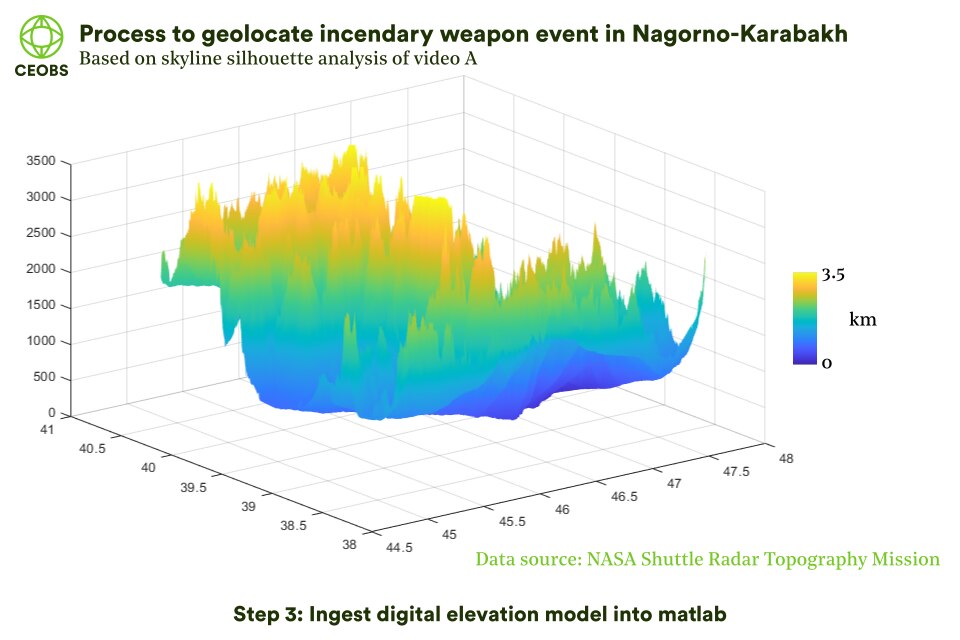

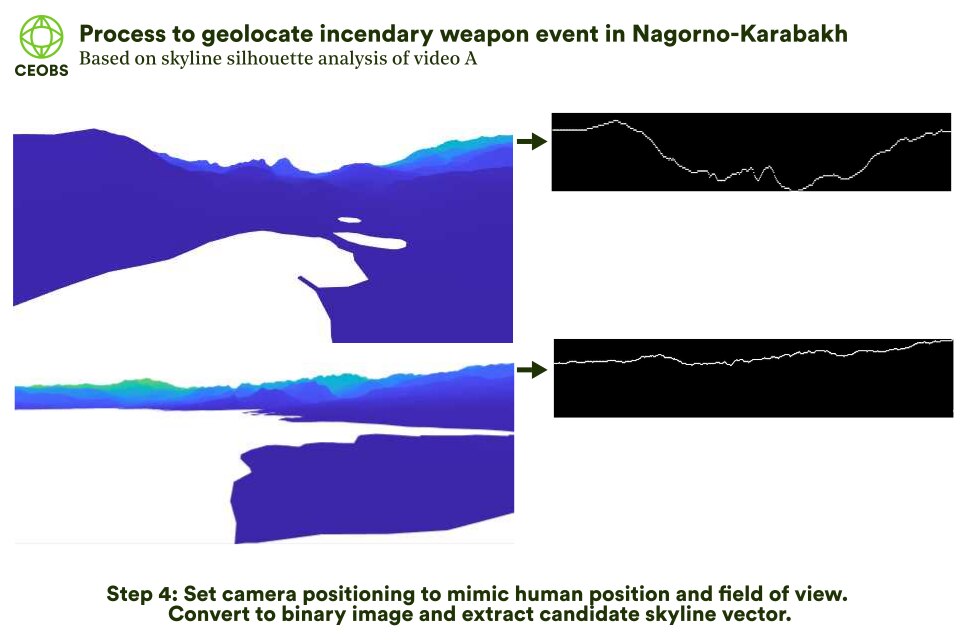

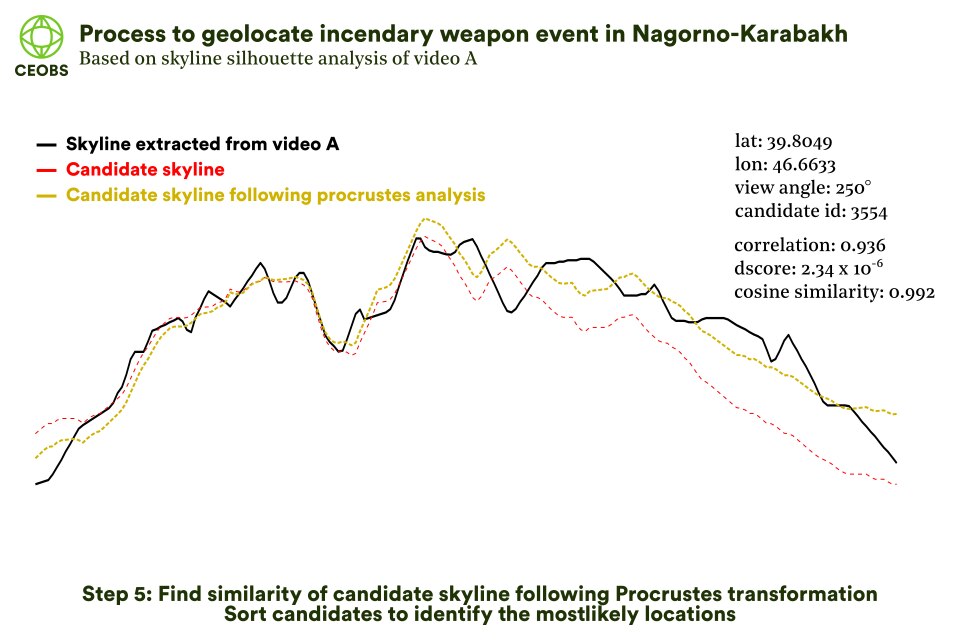

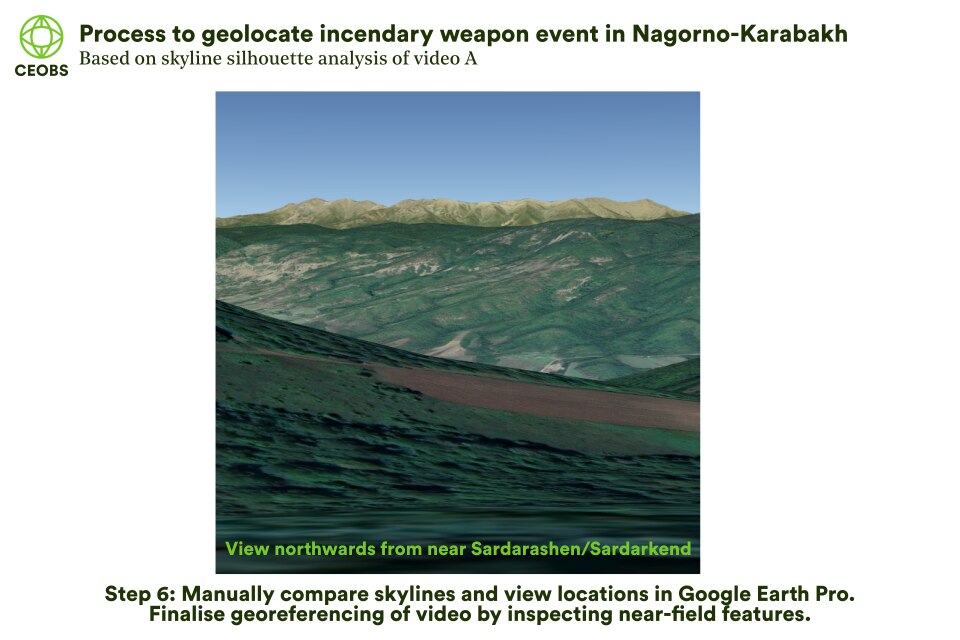

It is important to try to geolocate the locations where the incendiary weapons were used, in order to determine and address any environmental damage done, and prevent further harm. However, as we do not have intimate knowledge of the local area, we cannot take the approach of other open source investigators to identify the locations through Google Earth alone. Hence, we attempted a novel approach to geolocate the area in video A by matching the mountain outline silhouette to candidate skylines throughout Nagorno-Karabakh, generated using a digital elevation model (DEM).

The methodology is summarised in Figure 19 and fully expanded in the appendix. Unfortunately, this approach did not yield the exact location of the video, highlighting the difficulty of georeferencing without intimate local knowledge. The effort may have been more successful if there had not been compromise to meet our computational capacity, or the method more optimised. We welcome feedback, because we believe this method may work well and be a powerful open-source intelligence tool in other contexts.

Figure 19. Summary of approach to geolocate video A. Use left/right arrows to scroll through figures.

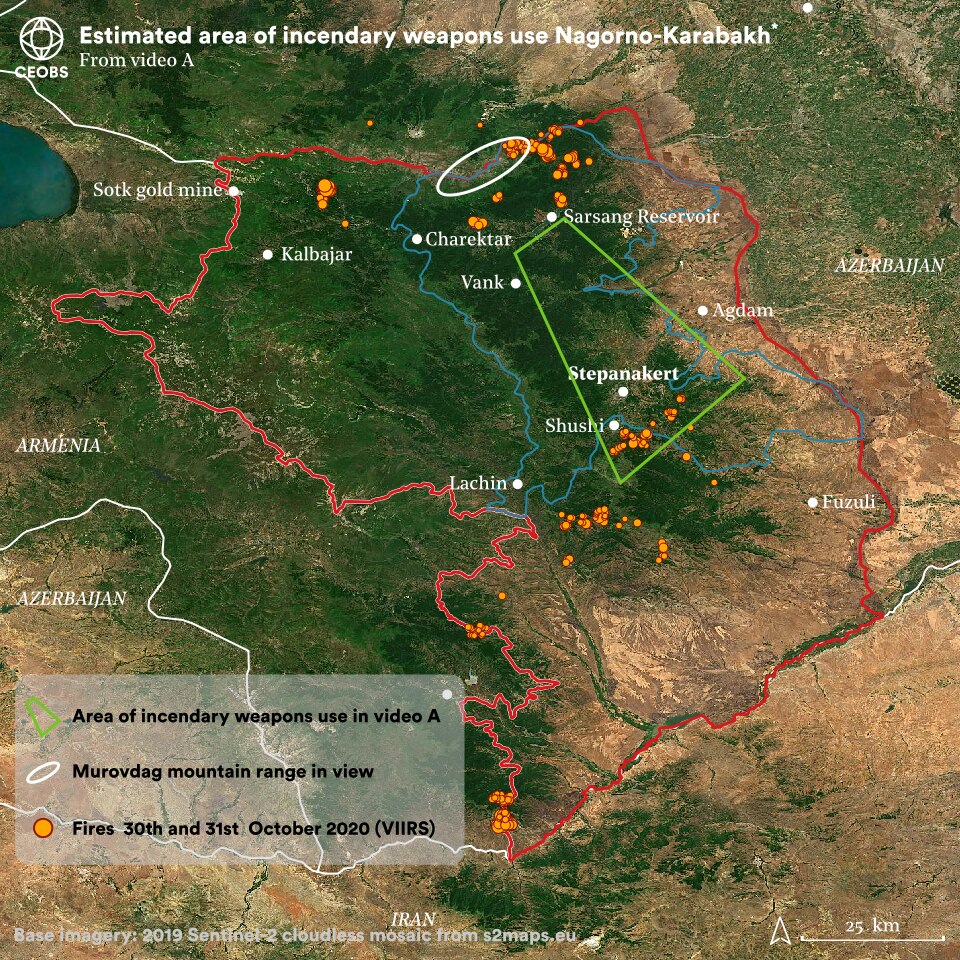

However, we tentatively estimate an approximate area. The candidate skylines that showed the best similarity to that in the video were those looking north-west towards the Murovdag mountain range, in the area highlighted in Figure 20.

We have not attempted a similar analysis on video C, given its peculiarity. The footage is filmed by Bars Media, an organisation that did not exist until the conflict started and seems to be a propaganda arm for the Armenian military. Furthermore, it strikes us as strange how nonchalant the soldiers are – walking around eating and smoking despite the incendiary weapons raining down – it all just seems a bit contrived.

Fig 20. Estimated area of the incendiary weapons use in video A.

Legal aspects

Customary international humanitarian law (IHL) states that ‘particular care must be taken to avoid, and in any event to minimise, incidental loss of civilian life, injury to civilians and damage to civilian objects’ if incendiary weapons are used. The natural environment is classed as a civilian object and should therefore also enjoy protection. For states party to Protocol III to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, it is prohibited to make forests or other kinds of plant cover the object of attack by incendiary weapons, except when these are used to cover, conceal or camouflage combatants or other military objectives, or are themselves military objectives. Neither Armenia or Azerbaijan are party to Protocol III. In spite of their intrinsically indiscriminate and inhumane nature, the regulation of incendiary weapons is notoriously weak and Protocol III has significant loopholes that reduce its effectiveness – excluding most multipurpose munitions and methods of launch.

In a joint ad hoc report on the use of incendiary weapons released on 3rd November, the Human Rights Defender of the Republic of Armenia and the Human Rights Ombudsman of the Republic of Artsakh alleged that attacks were illegal under this protocol, customary IHL and environmental law. The first line of argument was that the protocol was violated as civilians and civilian objects were the targets of the attacks, citing the proximity of the fires to settlements and that civilians were hiding from the fighting in the forests. It is further alleged that if the acts were conducted intentionally they may constitute a war crime.

The second line of argument was based on the damage sustained to the forests. However, one of the exemptions to this protocol is when natural elements are used to conceal military objectives. So, if there were munitions hidden under the canopy cover – a practise purported to occur – the attack would be legal. Presumably in an attempt to pre-empt this argument, the ad hoc report argues too much forest was burned for it all to conceivably be a military objective.11

This line of argument ignores the tendency of fires to spread, especially if adjacent areas are combustible and the weather is favourable. Referencing various protocols and advisory opinions, the report further argues the forest is an object indispensable to the survival of the civilian population, given it supports livelihoods, and thus its destruction is also illegal under IHL.12

Armenian legal analysis has also claimed the attacks would be illegal under domestic law based on their environmental impact. The government also appealed for an independent assessment by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), a call supported by the Armenian Bar Association.

Comparatively, and to the best of our knowledge, there was no equivalent legal reporting from Azerbaijan on the subject of incendiary weapons. However, the Prosecutor General’s office did file a criminal case against Armenians who burned forests in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the President has indicated that the country will sue Armenia for infrastructure damage – this may include environmental resources. Furthermore, the Azeri Commissioner for Human Rights wrote an appeal to various international organisations (UN, EU, OSCE, and more) on November 30th – the Day of Remembrance for all Victims of Chemical Warfare. In the appeal it was alleged that the Armenian government had severely violated many international obligations in respect to the conflict, including those associated with the use of white phosphorous. The incorrect suggestion that incendiary weapons were chemical weapons was rife on social media, and from both sides.

Legacy of the forest fires

The forest fires may have a significant and lasting environmental impact. As they were the sole environmental focus of the conflict it is possible some sort of remediation may occur, even if as a propaganda excise – for instance there are already Armenian plans to restore the forest as a war memorial, whilst Azeri tree planting in recaptured territory has reportedly started. The same attention is not guaranteed of the mosaic of other environmental consequences of the recent and historical fighting and tensions. We explore these below.

5. Water Resources

Summer 2020 water crisis in Azerbaijan

One of the missed dynamics of the conflict is that of water. In the build up to the conflict, Azerbaijan was in the midst of a water crisis. Over summer 2020, water levels in the Kura river, which flows into Azerbaijan from Georgia and Turkey, dropped by two and a half metres, remarkably resulting in seawater from the Caspian Sea flowing inland and upstream. Levels in the Mingachevir reservoir, the largest in the Caucasus, dropped by 16 metres. This had a significant impact on drinking and agricultural water supplies for rural Azeris, and in August it was reported that there was only water for two or three hours every night in Baku.

Declining water levels are attributed to over-abstraction for agriculture and poor management of water resources. In April 2020 the severity of the issue led to the Azeri president issuing a decree on the “rational” use of water, and instigating a commission to replenish water levels. In July it became a top-level agenda item for his administration – there are plans for the construction of ten new reservoirs. In the context of the recent fighting, this water crisis is relevant, as Nagorno-Karabakh is rich in water resources and, sitting upstream of Azeri agricultural land, moderates water flow via the deeply politicised Sarsang reservoir.

Pre-conflict water resources in Nagorno-Karabakh

The Azeris allege that the intentional mismanagement of the Sarsang reservoir has been eco-terrorism, with historical reports of flooding and the withholding of potable water to downstream consumers and farmers. This claim was ratified somewhat by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) in a December 2015 report, and January 2016 resolution #2085 entitled ‘Inhabitants of frontier regions of Azerbaijan are deliberately deprived of water’. The thrust of the resolution was that there was a deliberate deprivation of water to Azerbaijan and that this was a hostile act of environmental aggression, whilst the lack of reservoir maintenance posed a danger to those downstream. PACE also condemned the lack of co-operation from Armenian officials.

In turn, the Armenian delegation contested the PACE condemnation and questioned the objectivity of the Rapporteur, citing their apparent refusal to visit the area, whilst reacting angrily to the findings of the report. Along with the Nagorno-Karabakh authorities they counter-claimed that there was no irrigation water available for Nagorno-Karabakh residents, as the junction of the main canal of the Terter River was under Azeri control. This also meant the Azeris only went without water in the summer months. It was also claimed the reservoir water was only used for hydroelectric generation in winter, the profits from which were needed to ensure maintenance of the dam.

Given the poor outcomes for civilians on all sides it seems there were grounds for mutually beneficial co-operation – from 2013 up to as recently as 2019, the Nagorno-Karabakh authorities made approaches to their Azeri counterparts. These were rejected in order not to legitimise what was seen as the Armenian occupation. It could be argued that this position became entrenched following the strong language in the PACE resolution, which attributed significant blame to Armenia. The strength of this language was surprising given the seeming reliance of the PACE report on anecdotal evidence, flying in the face of their recommendation for technical hydrological and engineering inspections by independent bodies. Furthermore, it went against the position of the Minsk group,13 which had supported a co-operative approach, and even elicited a press release from them suggesting PACE were undermining their mandate.

In a review of transboundary water co-operation in the Caucasus, Veliyev et al., compare actions taken on the Sarsang and the similar Zonkar reservoir in South Ossetia, the de facto state in Georgia, where a depoliticisation of issues allowed a more successful outcome of essential maintenance. In contrast, it is succinctly summarised that in the case of Sarsang:

“It seems that the candid goal of both authorities is not to reach a resolution to address some urgent problems of the local communities, but rather use this issue as a mean to win on political terms by labelling the other as an aggressor or as non-cooperative.”

Figure 21. Key water resources in Nagorno-Karabakh.

An incentive for military action?

Given the failure of any cooperation mechanism, the chance to gain control of Nagorno-Karabakh’s water resources was clearly beneficial to Azeri economic and political interests – through stymying growing discontent at the water crisis and weakening a foe – and therefore possibly a factor leading to the decision to intensify the military operation. Ultimately, we may never know, although we do note the quick moves to tender for water management infrastructure following the taking of territory.

There are many strategically important water resources in the territory taken by Azerbaijan during the recent fighting – in particular the Khudaferin and Sugovushan (also known as Madagiz) reservoirs. Although Sarsang reservoir itself was not retaken, the taking of the Sugovushan reservoir allows partial control of its waters. Furthermore, the Sarsang hydroelectric power plant was also captured – just one of the 30 out of 36 hydroelectric plants now under Azeri control. It is unclear if the plant can continue operations or is dependent on management of the Sarsang.

Given the proximity of fires – potentially white phosphorous associated – and fighting in the watershed of the reservoir, there is a small possibility of contamination of the Sarsang. Testing of the water would be recommended – although it is unlikely this will be a priority for either party, it ought to occur in the event of an independent post-conflict environmental assessment.

There are also unconfirmed reports that the Armenian military fired missiles at the Oguz-Gabala-Baku water pipeline and Mingachevir reservoirs, both outside of Nagorno-Karabakh but key to water security in Azerbaijan.

In line with one of the main themes of this conflict, water resources and the Sarsang in particular were used in the disinformation war online. There was a reprehensible call to blow up the Sarsang and poison the rivers going into Azerbaijan. This was jumped upon by thousands of Twitter bots – all recently joined, with barely any followers, but using exactly the same phrase, to give the impression this was a serious risk and represented the Armenian position, rather than that of a sole ‘political scientist’ on his personal Facebook page with very few followers.

This doomsday escalation was reported on the Azeri side too, all be it before the fighting began. In response to an alleged (and contested) threat to the Mingachevir reservoir, the Azerbaijani Defense Ministry threatened a tit-for-tat response by striking the Metzamur nuclear facility in Armenia to cause a Chernobyl-style ‘Catastrophe’. How much this threat was theatre or a genuine response is unknown, but it is surely a positive sign that there has been no further mentions of it, even at the height of the fighting.

Against this backdrop, and the total failure of previous co-operation around water resources, it takes an optimist to see a positive outcome for all civilians in the region. Yet, it is likely that the Sarsang dam is still in need of essential maintenance – perhaps even more so since the fighting, and so co-operation still remains essential. Any future agreement on water resources needs to be based on a fair assessment of needs and production, and so will need to be depoliticised, which seems unlikely in the current climate. For example, Azerbaijan has now started blaming Armenia for the pollution of the Azar river which flows through both countries. Whilst this may be true – although no evidence has been publicly released – a co-operative route is not being taken. It is possible the water pressures in the South Caucasus may pose a future security risk, especially in a changing climate. Alternatively, with stronger independence now established, there may be scope for pragmatic under-the-radar cooperation.

6. Natural resources

Mining

Following the peace deal there have been disputes over the Sotk gold mine, the largest in Armenia and important for its finances. Whilst the mine was formerly on the Armenia-Karabakh border, it now sits on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, and on the 26th of November it was reported that Azeri forces had taken over the mine. Disputes and disinformation followed, but it now seems the demarcation of the border is finished, with the mine divided in two.

There is a history of environmental damage arising from the mining operations, particularly via water, soil and air pollution from explosive residues and heavy metals. There is potential risk to the environment via a number of conceivable avenues:

- Inaction leading to a serious incident with no response – as far as we can tell there have been no active operations at the site since the sudden stop as fighting began on September 29th.

- Even if activities restart, with the site fragmented and materials, equipment and buildings abandoned on what is now Azeri territory, accountability for unsafe materials or practises has likely diminished thus raising the potential for a serious incident.

- This may be compounded if former mine workers cannot return, with a loss of expertise and accountability. Mine workers have no idea how or if they will continue working.

- At the other extreme, there may be a drive to increase mining activity as a means of competition and provocation between the two parties, driving up tensions. This is dependent on how the mine is run, either by two separate entities or one. Comments on social media suggest that ownership has been transferred from GeoProMining (Russian/UK) to Anglo Asian Mining (Azeri), which had the mine on its list of contract areas in an October report, although this is unconfirmed.

- Transboundary pollution from future activities may lead to further conflict. This is not only a risk for air pollutants, but also for surface and groundwater – the mine is in the watershed of both Lake Sevan in Armenia and Lake Sarsang in Nagorno-Karabakh.

- If the area is heavily militarised there is a clear risk to critical infrastructure, which may lead to a serious incident.

Figure 22. Satellite imagery of the Sotk gold mine and how it straddles the Armenia-Azerbaijan border (location approximated here). Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data 2021.

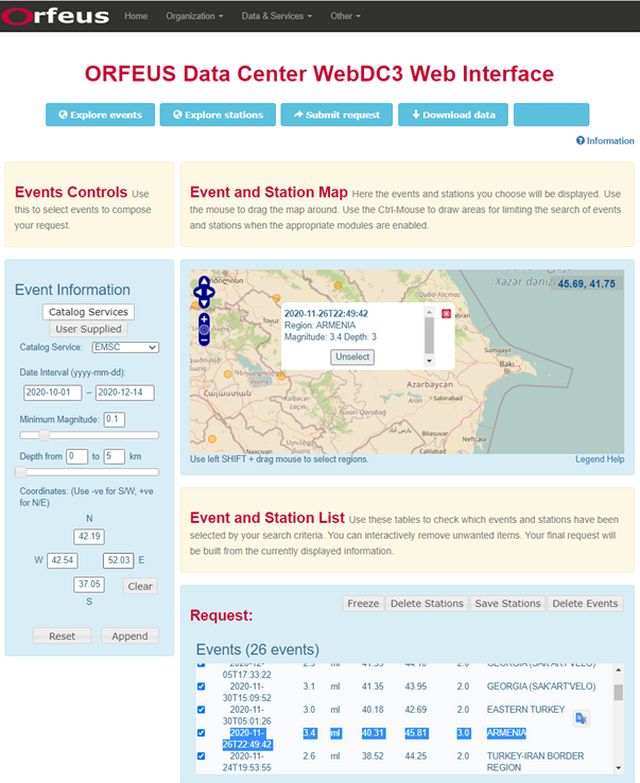

Curiously, coincidental or maybe in some way related to these military activities, there was a near surface seismic event recorded on the 26th November in the vicinity of the mine. This is based on data from the European Mediterranean Seismological Centre (EMSC) obtained on the Observatories and Research Facilities for European Seismology (ORFEUS) platform. Pinpointing the exact location of such activity is difficult, so although the reported coordinates are near the mine they may not be associated. A recent study found the data to have around a 50km location accuracy.

Figure 23. Seismic event recorded near the Sotk gold mine on the border of Armenia and Azerbaijan. Screenshot of the ORFEUS web platform https://www.orfeus-eu.org/webdc3/

In addition to ongoing extraction at Sotk, there is the 300km2 Vejnaly mining area, the ‘long lost mineral rich district’ that has seen limited use by the Armenians but is now in Azeri territory. There are plans to immediately start exploration once safe, with likely environmental consequences. Investors have been alerted, amid accusations that Anglo Asian Mining have been quick to exploit the conflict for profit.

Energy infrastructure

During the fighting there were reports from Azerbaijan that oil pipelines had come under attack several times, accusations that Armenia denied. This includes the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan route to Turkey, the Baku-Novorossiisk to Russia, the Western Route Export Pipeline to Georgia and the South Caucasus Pipeline – this is part of the Southern Gas Corridor, which supplies the EU and has only just started operating. We are unaware of any documentary evidence of these attacks, or even precise details of the targets to investigate with satellite imagery.

From an environmental-security perspective it could be argued that ultimately it was these pipelines that ensured Azeri success in the recent fighting, primarily due to the superior military they could fund, but perhaps also geopolitically in the peace deal. There are now plans afoot by the Azeri National Academy of Sciences to explore the potential for extracting the reported 200m tonnes of oil and 250bn m3 of gas in the captured territories.

7. Toxic remnants of war

Unexploded ordnance

Neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan are signatories to the mine-ban treaty and the region is contaminated with mines and UXO, causing deaths even after the ceasefire and likely into the future. The director of the Azeri National Agency for Mine Action estimated that the clearance activity will take 5-8 years and if the mines are mechanically removed, there will be landscape damage. Miles Hawthorn the operations manager of The HALO Trust noted that there had been a greater use of cluster munitions than conventional mines. Russian peacekeeping forces are also demining in the region, including forested areas near Stepanakert. The focus will not just be on remnants from the recent conflict – prior to the fighting it was estimated that more than 75 km2 of land was affected by legacy contamination.

Conflict debris

In addition to UXO, there is likely a significant environmental burden from conflict debris both from the recent conflict but also that of 1994. As just one example, there have been pictures circulating of a destroyed electrical substation in Stepanakert – this may be associated with toxic polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) contamination in the vicinity of the transformers. PCBs are a class of persistent organic pollutants and known carcinogens, governed by the Stockholm Convention, of which Armenia and Azerbaijan are signatories.

Indeed, there is a lot of damage around Stepanakert, as documented in the Artsakh Ombudsman’s October 18th report,14 which shows debris from buildings but also infrastructure such as hydropower stations and gas pipelines, which may contain specific toxic materials. It is likely this debris is a source of asbestos, silica, synthetic vitreous fibres and hexavalent chromium dusts, all associated with potentially harmful health effects.

Other specific locations may have very toxic legacies. For example, there are unconfirmed social media reports and a video of the Yanshag military base being destroyed by Armenian forces before it was due to be handed over to Azerbaijan. The only way to assure the safety of all these locations is by environmental testing, informing the remediation required, if any. This will ensure that there is no toxic legacy from the conflict. Particular care will be required from the Azeris in restoring the city of Agdam, which has remained destroyed and abandoned since fighting in the early 1990s, but was previously a hub of light industry.

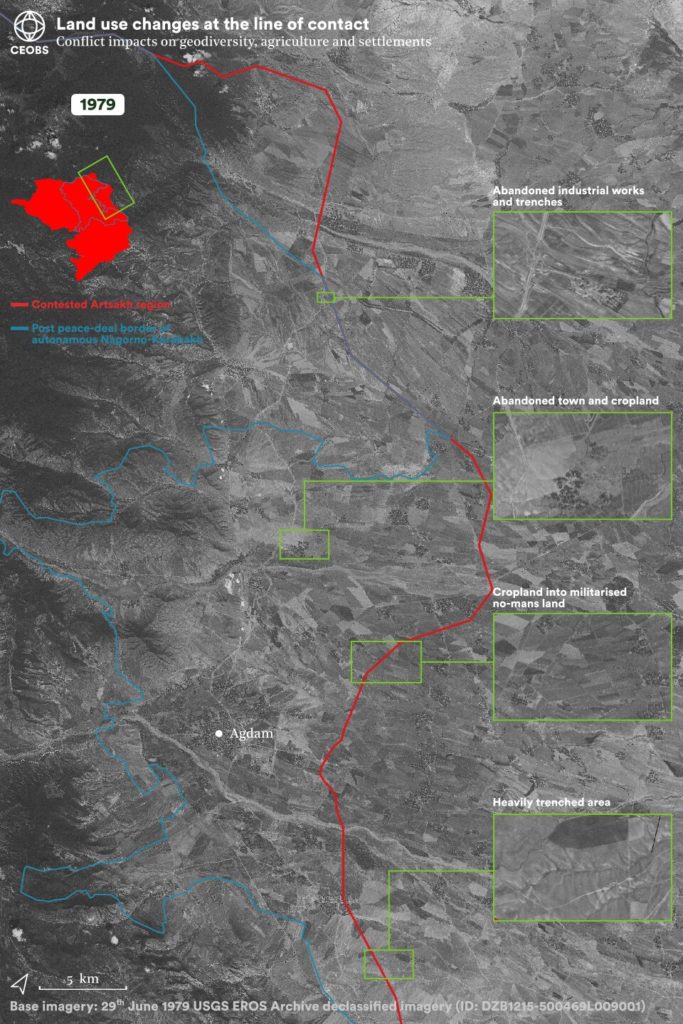

Figure 24. Satellite imagery along the line of contact in 1979 and 2019.

Landscape

Under the ceasefire agreement, two new militarised areas are set to be created. The first and most immediate of these will connect Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh via the Lachin corridor, a mere 5km wide. BirdLife International consider the area near Lachin, which is forested with juniper, as an important bird and biodiversity area, in particular for eagle, kestrel, grouse, red kites and other raptor species.

The route is still under consideration, but the second corridor will connect the main body of Azerbaijan to the Nakhchivan exclave, an area hitherto cut-off by Armenia. It is possible that the corridor will run along the river Aras, which borders Iran, and may constitute a threat to the riverine ecosystem. Already under pressure from mining pollution, it is not clear if the Armenian government will advocate for strong environmental protections. On the Iranian side of the Aras, a large area of the Kalibar Mountains is considered an important bird area. More hypothetically, this route offers new Turkish access to the Caspian Sea and, if it becomes a busy trading or pipeline route, an increase in air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions may be expected. In any case, the corridor will be heavily militarised in the first instance – nearly 2,000 Russian peacekeeping troops are set to be in the area for at least five years – and this too will likely come at an environmental cost. Indeed, there are already plans for a train line, which may have its own security implications and undermine the November 10 arrangement.

Along these corridors and the new lines of contact, it remains an open question as to how the land will be managed. It may be denuded and barren, like some areas along the line of contact between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan over the past three decades. Indeed, this barren landscape was used as part of the environmental disinformation war on social media, illustrating the disparity in stewardship between the Armenians and Azerbaijanis. That these areas are active fighting fronts, pitted and marked by trenches and UXO – seriously impacting geodiversity – and so an unwelcoming environment for any potential farmer, did not seem to register with those commenting underneath. Further into the Armenian controlled area, it does appear there has been a decrease in cropland under cultivation in some – but not all – of the area’s nearby abandoned settlements. This is based on the comparison of contemporary satellite imagery with that from declassified US satellite imagery from July 1979 in Figure 24. Many barren areas in 2019 were also bare in 1979 too. The historical imagery does reveal the scale of abandoned settlements in the line of contact area.

The historical comparison also illustrates the post-Soviet agricultural transformation in Azerbaijan, whereas the cropland within the contest area appears largely unchanged. In part this has been driven by the low price of fuel for machinery – and in particular for pumping groundwater, which has resulted in a slew of environmental problems and contributed to the current water crisis (see Section 5). To irrigate the farmland adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh, the Azeris dug 586 sub-artesian wells adjacent to the Sarsang reservoir, but the water level is reported to have decreased considerably. This has likely lowered the water table across the line of contact area.

With this in mind, there is an open question on the fate of landscape of the line of contact which is now in Azeri control. The area may be converted to intensive agricultural lands, as indicated by President Aliyev, but may face challenges in water access and land contamination from toxic remnants of war – proper testing of the soil will be required. Over the coming years it will be intriguing to see if the trenches and their infrastructure are also removed from the former line of contact area, and even further inland where satellite imagery shows trenches on farmland in Azeri villages. Likewise, if the hundreds of abandoned settlements are repopulated, it is possible there will be more pressure on the forests and their ecosystems. It is possible wildlife has thrived in these areas in the past three decades.

Tanks were heavily used by the Armenians and are known to impact the environment through rutting and turning over the soil. It was expected they would be key weapons in a war of attrition, but this was not the case – the use of drones by the Azeris secured the air space and allowed the easy targeting of surface targets, in particular trenches and tanks. Drone warfare in the conflict may have seen an updated form of a very old tactic – the destruction of forest cover through fire, but in this case with the specific intention of facilitating targeting by drones. The success of this tactic will have been noted. Indeed, if there is any form of guerrilla fighting it is possible the tactic may again be seen in Nagorno-Karabakh.

8. Final thoughts

Our early investigations reveal a range of environmental issues linked to the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. Although we have been able to shed further light on these using open source information, in particular earth observation data, there remains a need for on the ground environmental and technical assessments. Given the inability of either party to act neutrally – as evidenced by the environmental information war during the conflict – it is important that any assessment be independent. It is hoped the work in this report can help point to the locations requiring particular scrutiny.

Ultimately the environmental damage caused by the recent and historical fighting has had, and will continue to have, humanitarian consequences. This also includes psychological costs, given the importance attached to the natural environment as an aspect of cultural heritage. This seems clear from the emotion attached to social media posts around ecocide and environmental terrorism.

Indeed, as a shared cultural heritage it may be possible to flip the discourse on its head, and channel this concern into protection of the landscape and environment as a means to reconcile and build a sustainable peace – after all, it is a myth that the hatreds are ancient and intractable.

Analysis and report by Dr Eoghan Darbyshire, Researcher at CEOBS. Our thanks to Dr Nickolai Denisov and Otto Simonett from the Zoï Environment Network for their insights into the Caucasus and providing helpful feedback into this report.

Appendix

Geolocation of area in video A

The first step of this analysis was to stitch together frames from video A to generate the silhouette of the skyline in view. This was best accomplished manually in image processing software (Inkscape), as automatic image stitching methods (e.g. Hugin) struggled due to the constant changes from exploding and falling incendiary weapons. From this silhouette, the skyline was obtained by manually drawing a line along it – this gave a better result than thresholding the image and converting the binary to a vector.

The next step was to generate skylines from across Nagorno-Karabakh. To narrow down the locations to search we made two assumptions: 1) that the video was taken from a settlement, and 2) that the fires were measured from space. Open Street Map data provided latitude and longitudes for each of the 1,182 settlements, and was accessed through the QuickOSM plug in QGIS 3.16. As in Section 3, Suomi-NPP VIIRS NRT fire data was used.

We iterated through each of these locations and captured the skyline from different angles, assuming the camera height was 25 metres – an estimate of the best viewing point in the locale and sufficiently above the ground to avoid the influence of minor local slopes. To do this we plotted the digital elevation map as a 3-dimensional surface plot, and used geographic camera positioning to mimic the view of the video taker. For each location the camera position was rotated 360-degrees, in iterations of 10-degrees. The image of a 3-dimensional DEM was then captured and transformed into a binary image, from which the outline of the candidate skyline was extracted. To account for only a section of the candidate skyline matching the actual skyline from video A, subsets of the candidate skylines were also generated.

To compare the candidate skylines with the actual skyline generated from video A we used Procrustes analysis, a form of statistical shape analysis. We also undertook the analysis with a mirror image of the actual skyline, in the event it had been flipped during processing or upload. The Procrustes approach was required as we have no dimensional information on the skyline from video A, i.e. what the height difference is, what the perpendicular distance is, or how far away the mountains are. The Procrustes adjusted candidate skylines were then sorted from most similar to least similar, based on three measures: 1) Procrustes dissimilarity value, 2) correlation coefficient, and 3) cosine similarity. Plots of the top 50 most likely candidate skylines were then generated and manually sorted to remove unlikely matches. The remaining locations were then visited in Google Earth Pro and their similarity with the video manually assessed – this included the foothills visible in the foreground of the footage. Generation of candidate skylines and Procrustes analyses was performed in the MATLAB programming environment.

There are a number of limitations to our approach:

- The skyline stitching could be improved by a skilled image analyst

- The extraction of the candidate skylines from the Matlab camera view is likely subject to artefacts. The extraction code has been optimised to try minimise this, but given the number of candidates it is likely to have occurred – this also precludes any manual sorting or editing.

- The Procrustes transformation may not be the best way to compare the actual and candidate skylines. We did also try to a method comparing binary images, but this was less successful. Other approaches are likely out there, and we are happy to be alerted to them.

- The digital elevation model may not be high enough spatial resolution to capture the skyline shape in the video. However, because the key features seem a large distance from the viewer we expect this is unlikely.

- We were computationally limited to ensure a reasonable execution time. Two compromises were made:

1) The window size when viewing the DEM was relatively small (500 x 300 px). This has the effect of reducing the resolution of the DEM.

2) The number of observation points. The video may not have been taken in a settlement. A better approach would have been to iterate over a fine lat/lon grid, plus iterate different camera heights, and iterate over a finer number of angles.

- We used the following mainstream resources in writing our brief historical context, and refer those interested to these resources for further reading: Conflict Analysis Research Centre (CARC) at the University of Kent blog post (https://blogs.kent.ac.uk/carc/2018/04/15/the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict), BBC Nagorno-Karabakh profile (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-18270325), Crisis Group conflict explainer (https://www.crisisgroup.org/content/nagorno-karabakh-conflict-visual-explainer), National Geographic (https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2020/10/how-the-nagorno-karabakh-conflict-has-been-shaped-by-past-empires), Encyclopaedia Britannica (https://www.britannica.com/place/Nagorno-Karabakh), and Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Nagorno-Karabakh)

- “Nagorno” is from the Russian meaning “mountainous”, whereas Karabakh is a thought to transliterate as “black garden” and is a compound of the Turkic word “kara” and Persian word “bagh”. However, Armenians officially refer to the area as the Artsakh Republic, as it lacks the non-Armenian influences in “Nagorno-Karabakh”. Azeris refer to the area as Qarabağ.

- We note that the linguistically correct form is Nagorny Karabakh. Nagorno-Karabakh is a compound adjective in Russian and thus cannot be used as a noun, whilst Nagorny Karabakh can be used as a noun (as the adjective Nagorny defines the noun Karabakh).

- Armenia is ranked 61st out of 180 countries

- CEOBS was approached.

- As of January 2020 there were 1.5 million users in Armenia and 3.7 million users in Azerbaijan

-

Correction 9th March 2021.

An earlier version of this document stated “the total area of high or moderately-high burned land as 2,734 km2“.

This value was erroneous. The reason for the error was the addition of values from the wrong burned area classes. Instead of adding the “high severity” and “moderate-high severity” classes, values from the “enhanced regrowth, low” and “enhanced regrowth, high” classes were added. The error arose as the author misread the order of the list of burned area classes. For full transparency a screenshot of the source of this error can be found at this link.

Note, the corrected burned area of 102 km2 doesn’t represent the whole burned area, just the area which was classified as burned with the highest or a moderate-high severity. i.e. the most impacted areas which will take the longest to recover. Estimating all the burned area is quite difficult to do accurately, as the locations which are classified as being burned with a low severity could actually be artefacts in data – to discriminate between the two would require deeper analysis.

- 100m 2019 Copernicus Global Land Service maps based on the PROBA-V sensor, simplified by CEOBS into only seven categories

- According to the translations circulating on social media that we have had to rely on.