To protect the ecosystems that underpin livelihoods in conflicts, we need to think beyond just protecting biodiversity, we also need to protect what’s under our feet.

A motion on biodiversity and conflicts that was tabled ahead of the IUCN’s World Conservation Congress also highlighted the need to protect geodiversity. But what is geodiversity, how is it affected by armed conflicts, and why is protecting it important for ecosystems and livelihoods? Dr Kevin Kiernan explains.

Geodiversity, its values and uses

The IUCN motion on the Protection of the environment in relation to armed conflict acknowledges that in addition to the harm that armed conflict causes to biota it “also generates the loss of geodiversity and its geological heritage and the places of geological interest that are also part of the environment”. Geodiversity encompasses geological formations, landforms and soils. Components of geodiversity including significant fossil assemblages in bedrock geological units, landforms such as caves or waterfalls, and different types of soil profiles, can all be very important targets for nature conservation initiatives in their own right. In addition, geodiversity provides the essential diversity of habitat niches upon which biodiversity is dependant, and it often also underpins the livelihoods of those living in conflict zones.

As with biodiversity, there are many different “species” of minerals and other elements of geodiversity, including different types of landforms and soils. There are also different landform “communities”, that is, assemblages of different landforms that are genetically inter-related. As with biological species, some types of landforms and landform assemblages are common and some are rare, some are robust and some are fragile. In addition, even a common and outwardly uninteresting-looking landform may be of conservation significance if it contains certain sediments that provide an archive of palaeoenvironmental information, biological species that are reliant upon it as habitat, or if it contains archaeological relicts or other special phenomena.

While international humanitarian law, which is traditionally thought to provide for the legal protection of the environment in times of war, is mainly underpinned by anthropocentric perspectives, this is only part of the story, because more ecocentric perspectives are also relevant. For example, the preamble to the Convention on Biodiversity notes that its signatory parties are conscious of the “intrinsic” values of biodiversity. Similarly, physical phenomena such as caves, hills and waterfalls are important in their own right for their existence and intrinsic values, much as are whales or ancient forest trees.

Many people consider that this existence value alone demands respectful stewardship of environmental phenomena, including landforms, simply because they are just as legitimate a part of the cosmos as is the Earth’s biota, including humans. Additionally, geodiversity is also fundamental to the functioning of natural process systems, including ecosystems. From a more anthropocentric perspective, geodiversity is of instrumental value to humans as a source of various goods, ranging across material, spiritual, inspirational, scientific and other uses, including the maintenance of ecosystem services upon which human communities are dependent, such as soil in which to grow food, and natural water supplies.

The nature of damage

During active conflict the environment inevitably suffers because the practitioners of war routinely employ, as their standard tools of trade, not merely the machetes, chainsaws and graders used by those enterprises that typically attract the attention of environmentalists, but instead the most massively destructive explosive tools ever devised and produced by humanity. They may also employ a wide range of other types of weapons that can include chemical and biological agents. There is often a selective collapse of effective governance, including environmental governance, thereby allowing corruption to flourish, illegal poaching or the theft of natural resources.

The physical characteristics of some landscapes, such as the presence of rugged inaccessible terrain and hidden caves, can make them particularly useful as bases for guerrilla-style operations. The environmental damage this can cause is compounded when the presence of a base draws fire from opposing forces. Those same physical characteristics or rugged inaccessible terrain and natural shelter also make some areas attractive as sanctuaries for non-combatants who are displaced by armed conflict, and geo-environmental degradation can also result from displacement pressures.

The damage caused to geodiversity by war can occur at a variety of scales. Erosion has affected vast areas of Indochina due to military operations. In the Dolomites of Italy some entire mountains summits were blown apart during WWI, many major rock-falls and collapses were triggered, and the mountains remain strewn with war-time debris. But at a much smaller scale, delicate stalactites and crystal floors that take millennia to form inside limestone cave systems have commonly fallen victim to the impacts of war, such as the passage of troops sequestered underground.

It is not only the direct physical damage to geological features, landforms, soils and hydrology that needs to be taken into account. We also need to consider the consequences of environmental contaminants and their affects upon aquifers and waterways, some of which may transmit contaminants well beyond a battlefield, their dependent biota, and the ecosystem services from which the human residents benefit.

Determining harm to geodiversity

Determinants of the degree of damage caused to geodiversity by war include the nature of the activities undertaken, the intensity with which energy is applied, the materials utilised, particular military strategies, the environmental and other expertise employed, and social factors including the environmental consciences of the practitioners of war.

Objectively, because landforms are defined by their natural contours, any anthropogenic change to those contours, at whatever scale, necessarily represents damage. However, ascertaining the significance of that damage is more challenging than merely identifying its occurrence, not only because of a paucity of pre-conflict data against which to compare, but more particularly because human value judgements are entailed. What one person may perceive as unacceptable damage may be perceived by another as inconsequential change.

Questions that invariably require resolution include the proportion of the feature that has been damaged; the significance of the part damaged to the broader functioning of the natural system; whether it is a feature that has no capacity to self-heal under the present-day climate; the extent to which a perceived value of the feature has been compromised by the damage sustained; and competing perspectives in relation to instrumental or economic gain versus the protection of nature. Potential instrumental gain could of course include the use of particular topography for military purposes.

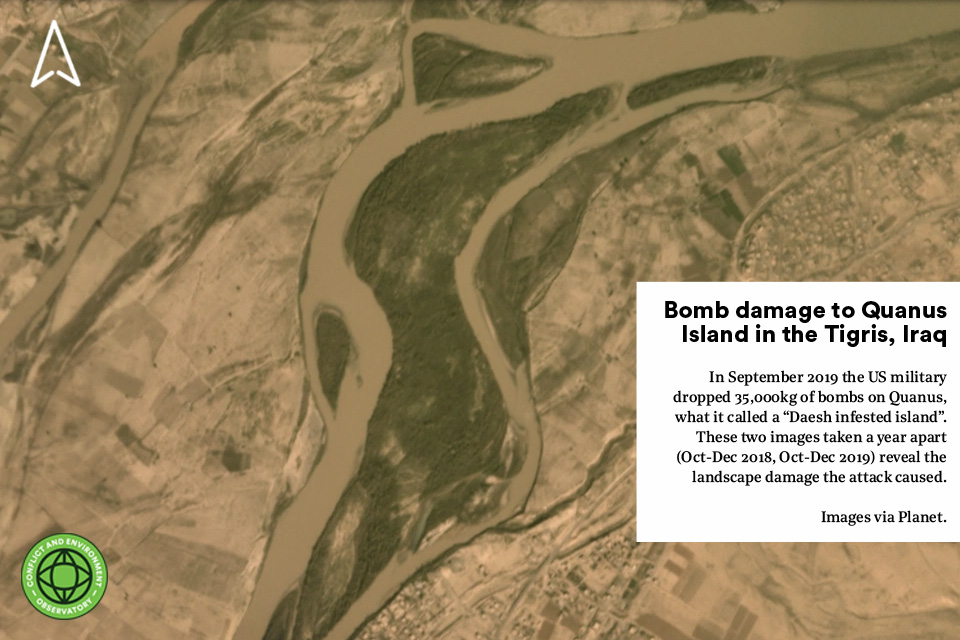

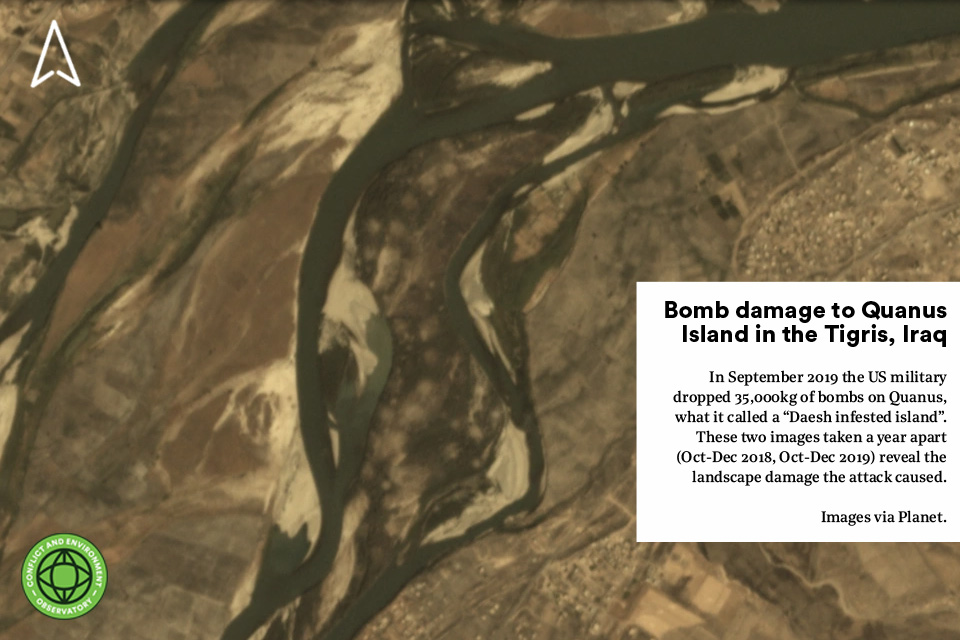

The trenches and craters produced during WWI that remain conspicuous in France and elsewhere are by no means the earliest impacts of armed conflict on geodiversity that remain extant. Elsewhere, four decades since the cessation of conflict in Laos, bomb craters remain discernible at densities that commonly exceed 200/km2 and in some cases exceed 800/km2. This landform damage also implies major loss of soil capital, full recovery from which is likely to take millennia. Such disruptions of natural ground contours can often cause derangement of the natural patterns of rainwater runoff at a variety of scales, the wartime patterns then being inherited by subsequent water flows and new channels being eroded into the landscape. Some natural depressions no larger than bomb craters and channels no larger than military ditches, formed from similar earthy materials, have survived since the last ice age and earlier. There is no reason to believe that some military damage to landscapes will be any less long-lasting.

Not just dirt

Understanding of the potential for war to damage soils is impeded both by under-recognition of the particular vulnerability of some soils, and also by a common failure to realise that soil is not just “dirt”. For loose lithic material at the Earth’s surface to become a soil requires that it be converted into a potential medium for plant growth through pedogenesis. Pedogenesis involves various progressive processes, including the weathering of minerals; leaching; the shrinking and swelling of clay minerals; the addition of aerosol inputs; enrichment by organic matter; internal redistributions of matter; the development of soil structure; and differentiation into soil horizons.

Soil formation takes a long time. Even where climatic conditions are warm and moist, rock weathering rates may allow no more than 1m of soil to form in 50,000 years on most rock types, the global median rate of soil formation being about 0.06mm/year. The uppermost soil horizons are generally the most productive part of a soil profile. Both Nature and Humanity lose that fragile, life-sustaining film across the landscape if anthropogenic activities cause accelerated erosion; churning and profile mixing, or inversion by traffic; structural damage by compaction; nutrient depletion; or soil pollution.

All these impacts occur readily during wartime due to the passage of vehicles, the detonation of explosive ordnance and various other activities. A single event can cause instantaneous soil loss (in seconds) due to initial mass displacement, and subsequent progressive soil loss (minutes-millennia) due to derailment of natural processes, such as predisposing a slope to soil erosion. Both instantaneous and progressive damage reduce the productivity of a soil, and damage to soil resources implies ongoing environmental, economic and social harm.

The odd bomb crater may in time be opportunistically employed as a fowl-yard or fish-pond, and a denuded hill may become masked by a veneer of green relatively quickly, perhaps even sufficient for a farmer to be able to graze livestock or grow some food. But that obscuring green film says nothing about the true productivity the soil once had, but which has been lost due to obliteration of the soil profile when the bomb detonated, or the potential soil contamination by the scattering of harmful bomb residues. Both Nature and future generations are denied their legitimate inheritance when the reality of the damage caused is the extirpation of landforms and soils that took millennia to form – and will take a similar length of time to recover.

The conflict phase is only part of the problem

The impacts of military activity entail more than just the direct physical damage caused in theatres of battle, and the long-term effects of war are generally far more serious than just the damage incurred during the actual conflict phase. Even before a battle is enacted there are military environmental impacts associated with weapons development, war industries often generating severe impacts that range from extraction of the resources they process to evacuation of the waste products produced. Military training activities can also cause serious damage to geodiversity.

During the so-called “post-conflict” phase after battlefield activity has concluded there are a variety of additional impacts. Some are associated with the process and completeness of demilitarisation. Others involve changes to natural processes caused by ground surface damage such as devegetation and soil surface exposure to erosion, trench and tunnel construction, bomb crater formation, the degradation of abandoned materials, and impacts associated with the presence and removal of explosive remnants of war, such as land mines. The mechanical removal of mines can cause significant disruption to soils.

A post-war governance vacuum and populations driven to desperation in a quest to rebuild their lives often adds to the environmental pressures. Moreover, this so-called “post-conflict” phase is in many respects a misnomer because in the wake of the main battles there are almost invariably ongoing subsidiary conflicts as factions contest supremacy or vested interests seek to cement their economic or political position, again often with implications for geodiversity.

Assessment and progress

Additional Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions prohibits the deployment of means or methods of warfare that will cumulatively cause, or may be expected to cause, environmental damage that is severe, widespread and long-term; evaluating whether this proscription has been complied with demands post-conflict environmental assessments. However the limited scope of the assessments now routinely undertaken by UN agencies reflects the fact that the existing literature regarding the impact of war on the natural environment typically focuses only on some biological impacts and water contamination issues. Any mention of geodiversity is limited to essentially anecdotal observations regarding possible soil damage. This must change.

The severity of the damage caused in some past conflicts is indisputable. The outrageous extent of the despoliation in Indochina that stimulated attempts to improve the environmental laws of war ought not to be used as a benchmark against which to measure what might constitute ‘widespread’. Human communities faced with damage to all the productive land at their disposal have every reason to consider such damage to be ‘widespread’. And that the damage armed conflicts cause to geodiversity is often exceedingly long term in nature is undeniable.

It seems desirable that assessment of damage to geodiversity, and initiation of such remedial measures as may be warranted, should both commence as soon as possible, and be combined with appropriate compensatory measures for communities adversely affected. However, only the most conspicuous types of damage to geodiversity will be evident immediately upon cessation of active hostilities. The ultimate magnitude of the damage inflicted by war may not become apparent until many years or decades afterwards.

As part of its mandate to develop and codify international law, the UN’s International Law Commission (ILC) has recently adopted a set of draft principles designed to improve protection of the environment from the damage caused by armed conflicts. Among the ILC draft principles with the potential to better safeguard geodiversity is Principle 4, which holds that states should designate areas of major environmental and cultural importance as protected areas.

While a pre-conflict national park or World Heritage Area that contains important geoheritage is an obvious candidate, there is also provision for designation subsequent to a conflict commencing. Such geoheritage as a spring that is held sacred by indigenous people, or rugged terrain that allows people to maintain a traditional lifestyle, have both natural and cultural heritage importance. Consistent with the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, draft principle 5 prescribes protection of environments inhabited by indigenous peoples, and post conflict remediation of any damage done in consultation with them.

Because environmental damage can constitute a war crime under international law, neither the gathering of forensic geomorphological evidence, nor the account of war reparations should be closed prematurely. Against this background, ILC draft principle 26 on ‘relief and assistance’ could provide the requisite legal machinery, as it stipulates that when the source of environmental damage in relation to armed conflict is unidentified, or reparation is unavailable, states are encouraged to take appropriate measures so that the damage does nor remain unrepaired or uncompensated.

Pillage, the illegal misappropriation of state, communal or private property from within the territory of a party to an armed conflict, or an occupied territory, is prohibited under draft principle 18. From a geodiversity perspective, the natural resources that might most readily come to mind for most people are mineral deposits susceptible to mining, and gems, with the scale of any theft by mining likely to be dependent upon the duration and security of occupation. However, just as there are ready markets for looted cultural antiquities acquired through illicit trade networks involving individuals, criminal gangs and terrorists, so too is there a ready market for some other easily transported elements of geodiversity, such as important fossils, interesting mineral crystals and samples of rare minerals that are valued by collectors.

However, the potential effectiveness of designated protected areas in safeguarding geodiversity can sometimes be negated. Draft principle 17 limits their protection to situations where sites do not contain a military objective, a limitation also contained in the 1954 Hague Convention mechanisms for cultural property protection. Some important cultural sites suffer wartime damage for reasons not too dissimilar from those that gave rise to their cultural heritage significance in the first place, such as an original strategically useful position in the landscape that is also taken advantage of by protagonists in later conflicts. So too can some sites of natural heritage importance, such as the forests defoliated in Indochina because they provided cover for opposition troops, or rugged mountain terrain conducive to guerrilla operations, effectively be their own worst enemy. Such things compound the difficulties of ensuring compliance with the best intended legal mechanisms.

The environmental degradation caused by displaced persons in the areas they are located was also addressed ILC. Draft principle 8, which urges states, international organisations and other relevant actors to take appropriate measures to prevent and mitigate environmental degradation in areas where persons displaced by armed conflict are located, could be operationalised so as to encompass geo-environmental degradation. Draft principle 25’s call for relevant actors to cooperate with respect to post-armed conflict assessments and remedial measures, could also be used to address harm to geodiversity.

Protecting environmental integrity

The environmental harm that war inflicts upon geodiversity is an important but inadequately considered topic in its own right. Comprehensively safeguarding geodiversity is also fundamental to the effective conservation of biodiversity, given that geodiversity provides the requisite stage upon which all the dramas of life are enacted. Geodiversity and biodiversity really need to be addressed concurrently, hence a more all-encompassing concept such as “enviro-diversity” might provide a more useful lens through which to view the environmental damage caused by armed conflict, and promote an outlook that is less conducive to the presently common preoccupation with biota alone.

And, while the establishment and safeguarding of protected areas is an encouraging development and is highly desirable, it is not just ‘special’ places that are at risk of damage due to armed conflict. Other areas of importance and most human communities are likely to remain outside the boundaries of any protected areas established to protect the most special places, and virtually all armed conflict constitutes a war on the environment.

Dr Kevin Kiernan is a geomorphologist who has researched the geo-environmental impacts of armed conflict in Indochina and Europe.