Challenging the growth of environmental disinformation in armed conflicts will take the concerted efforts of all stakeholders.

Environmental disaster? War crime? Ecological terrorism? A polarised and omnipresent social media is turbocharging the manipulation of environmental information during conflicts. While the use of environmental information for propaganda purposes isn’t new, what is new is the pace and volume of claims. From Gaza, to Ukraine and Yemen, distortion, manipulation and misinformation are rife. In this extended blog, Doug Weir and Dr Nickolai Denisov take a look at how and why environmental information gets distorted during conflicts, why it’s important to challenge digital propaganda and how it might be done.

The most endangered natural resource

In his introduction to the 1999 UN Environment Programme (UNEP) study on the environmental consequences of the Kosovo conflict, Balkan Task Force chairman Pekka Haavisto reflected that: “Perhaps the most endangered natural resource in times of war is truth”. In paraphrasing Sun Tzu and Aeschylus, he had sought to draw attention to the conflict’s competing environmental narratives. The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and neighbouring countries had feared widespread ecological damage and destruction, while NATO assured the world that its highly sophisticated weapons would enable them to minimise collateral damage to the environment.

The UNEP assessment ultimately helped inform the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia’s (ICTY) decision over whether NATO members had a case to answer for the damage they had caused to the environment. Undertaken shortly after the conflict, it found that fears of a region-wide environmental catastrophe were unfounded. Nevertheless, the assessment did find that NATO’s use of “highly sophisticated” weapons against a number of industrial facilities had created pollution hotspots that posed threats to human health. Expert observers later noted that:

“NATO failed to explain convincingly why its remarkably precise and thus potentially highly discriminate air force needed to destroy the [Pancevo] storage tanks, thus burning or spilling staggering quantities of liquid hydrocarbons and chemicals, rather than less harmfully targeting the adjacent but separate refinery installations, or, far better still, precisely hitting the more discrete river port, road, and rail nodes to stop loading, transportation, and distribution of the oil and chemicals.”

In spite of the damage that the assessment identified, the ICTY’s hands were bound by the impossibly high thresholds required to breach international humanitarian law’s (IHL) environmental provisions. The ICTY was also hampered by an absence of information on the medium and long-term consequences of the conflict on the environment, and for human health. The situation was compounded further by a lack of clarity over the pre-conflict environmental conditions at the sites targeted by NATO, where a history of poor pollution control made it difficult to distinguish what had been caused by the conflict.

The Serbian example highlights a number of themes of relevance to an examination of how environmental information can become distorted during times of war. Firstly, the environment is inevitably made part of the conflict, and parties to it often have diametrically opposed interests in how environmental narratives are presented. Secondly, there is often an environmental information vacuum during conflicts, usually extending well into their aftermath. This is primarily the result of a lack of access to affected areas, and to the absence of neutral monitoring. And thirdly, environmental damage that is claimed as a war crime by parties to a conflict, or their supporters, may be nothing of the sort. However, this can simply reflect the inadequacy of the law, the lack of available data, or the conscious or unconscious bias of observers, rather than the nature of the damage itself.

Two decades on from the Kosovo conflict, and with society living in information bubbles informed and poisoned by increasingly partisan social media, the era of fake news is upon us. It should therefore come as no surprise that truth about the environmental consequences of conflicts is more endangered than ever.

Shades of reality

The environmental information vacuum associated with conflicts, and the competing narratives from conflict parties, can both strongly influence how threats are characterised. In turn this vacuum can create and sustain the conditions that allow for three shades of reality. These could be broadly classified as uncertainty, the selective choice of facts for political gain, and the active weaponisation and manipulation of environmental data.

Uncertainty, ignorance and confusion

As noted above, uncertainty – and its colleagues, ignorance and confusion – is often unavoidable. Conflicts may take place in areas with little or no monitoring infrastructure. Where it does exist, those responsible for it may have been forced to flee, infrastructure may be rendered inoperable or monitoring sites made inaccessible. What information that is available will invariably be incomplete, and inadequate to conclusively determine the extent of any harm, or who was responsible.

The correct response in such situations should be for all relevant actors, be they states, international organisations or civil society, to utilise the tools at their disposal to help clarify any risks to human health or ecosystems; an often lengthy process, certainly as far as the traditional media’s news cycles are concerned. However, where potential risks are identified, the tendency is for alarm bells to be rung. The term “environmental disaster” has now become the political, and traditional and social media shorthand for describing events of wildly varying severity. Given the low priority afforded to the environment in conflict, these alarms can serve a useful purpose. But in many cases the claims associated with them may not survive later and more sober analysis. Needless to say, outright denials of harm can be just as destructive for efforts to find solutions to the environmental problems caused by conflicts as sensationalised claims are.

The selective choice of facts for political gain

It will come as no surprise that everything becomes politicised in the context of conflicts, and the environment is no exception. This politicisation ensures that the selective framing of environmental damage as a political tool by states and other actors is commonplace. While at times this may be unconscious, more often than not it is purposeful; often taking the form of criticism by one party of the actions of another, to distract or deflect attention from their own conduct.

Take for example Russia’s intervention in a July 2018 UN Security Council debate on climate security. The intervention was part of an increasingly predictable pattern of “whattaboutery”, and a political strategy of criticising others while ignoring the environmental impact that its own military tactics have had, most notably in the Syrian conflict. Such tactics have included the widespread targeting of oil installations, and have also facilitated the environmentally damaging military policies of the Syrian government. Nevertheless, the Russian representative commented thus:

“If we are so principled about [climate change and security], why are we always silent during the discussions initiated on this pretext about a no less serious aspect of the issue, the damage to the environment that results from violent military operations and unilateral sanctions, a glaring example of which have been the bombings of Yugoslavia, Libya and Syria by Western coalitions? It is strange, to say the least, that no speakers today have expressed concern about the massive environmental damage that such action inflicts, not to mention the colossal harm to the health of the citizens of those countries.”

Syria too has sought to finesse historical fact. Speaking at the third session of the UN Environment Assembly in 2017, its delegation rightly highlighted the “environmental disaster” that has resulted from its conflict, including the damage to its oil industry, but attributed the blame for both that and for damage to its vital infrastructure and dams to the “international alliance”. Clearly this practice is not unique to particular states, for example, western states invariably highlight the precision of their weapons and their tireless efforts to minimise collateral damage to civilians or the environment, while avoiding discussion on what Russia rightly acknowledges as the “glaring examples” of collapsed states and poorly planned interventions.

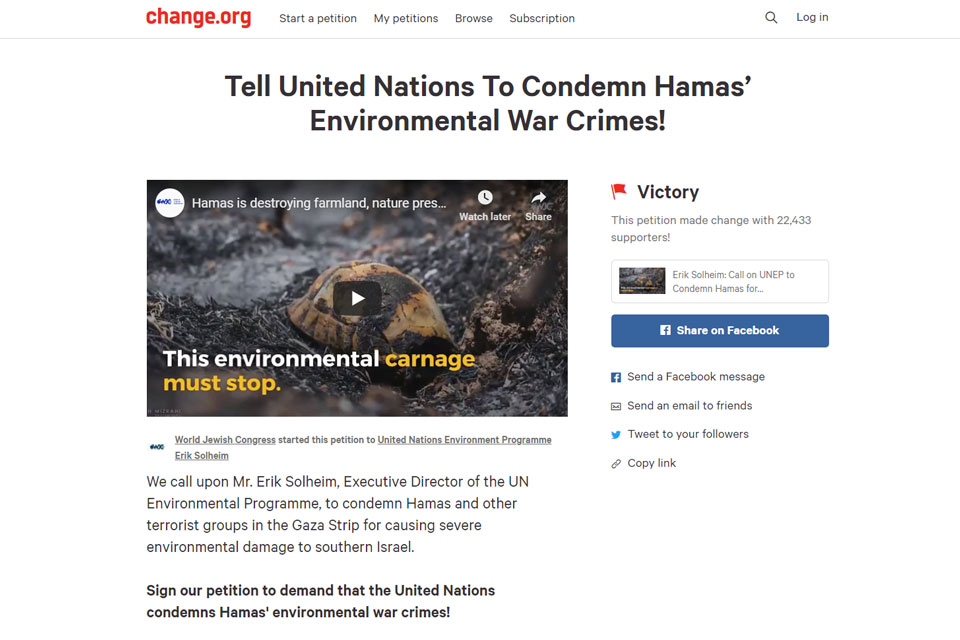

Selective political framings are also employed by non-state actors. The use of incendiary kites by protestors in Gaza, which began in 2018, has damaged agricultural and protected natural areas in Israel. The Israeli government struggled to respond appropriately to this new tactic so Jewish advocacy organisations took matters into their own hands. The World Jewish Congress launched a Change.org petition directed at the then head of UN Environment Erik Solheim, demanding that “the United Nations condemns Hamas’ environmental war crimes!”. The petition highlighted the health and environmental consequences of both the kites and the burning of tyres by “Hamas operatives and other terrorists”. In doing so it cited Article 35 (3) of Additional Protocol 1 of the Geneva Conventions and its prohibition on methods or means of warfare which are intended, or may be expected, to cause widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment.

However, the petition didn’t mention that Israel is not party to Additional Protocol 1, or to Protocol III of the Convention on Conventional Weapons, and its prohibitions on incendiary weapons. Nor did it consider that Article 35’s cumulative damage threshold would be unlikely to be breached by the harm caused by the kites, or mention Israel’s stated lack of enthusiasm for efforts to strengthen the legal framework protecting the environment in relation to armed conflicts. Nevertheless, the petition ultimately attracted 22,000 signatures, and was handed over to a UN Environment representative in New York, amidst talk of Israeli farmers pursuing a Rome Statute case at the International Criminal Court. Perhaps ironically, the period had seen its target, Erik Solheim, continue protracted negotiations with Israel – ongoing since 2016 – over access to the Gaza Strip for a long-overdue post-conflict environmental assessment. An assessment made necessary by the Israeli occupation and recurring periods of intense conflict.

The selective framing or utilisation of environmental harm in conflicts is so common as to be the norm. In the Gaza example above it was aided by an online petition site and a GIS platform. But the internet has also provided a new vehicle for the more active manipulation of information on environmental threats, with social media facilitating the rapid distribution of dubious claims within the echo chambers of eagerly soundproofed bubbles. The three cases below were all made possible by the power of social media.

The active weaponisation and manipulation of environmental data

Case 1: That time a Crimean town was poisoned

On the 23-24th August 2018, an incident at a chemical plant in Russian-occupied Crimea covered the nearby town of Armyansk with sulphuric acid, after gaseous sulphur compounds released from the facility mixed with moisture in the air. Metal objects were left with a coating of rust, scores of people began reporting breathing difficulties, and in the days that followed bird deaths were reported and trees began to turn brown. The people of Armyansk took to social media to report the problems but they weren’t publicly acknowledged by the Russian-backed administration until the 28th, when it was claimed that there was no risk to health. A government envoy appeared from Moscow the same day and admitted that the incident might be linked to the Crimean Titan titanium plant to the north of the town. State media began to downplay the risks, claiming that official monitoring had not revealed excess pollution, even as more and more local people began to report health problems.

The conflict between Ukraine, Russia and its proxies has been fought as much on social media as it has on the ground. Shortly after news emerged of the leak, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence tweeted that it was the result of damage to the plant or storage ponds caused by Russian military training. The plant produces acid waste water as a by-product of titanium production – stored in large ponds adjacent to the plant – and also produces sulphuric acid for use in the chemical industry. Once they had stopped denying that there were any risks to the people or Armyansk, the Russian-backed Crimean authorities countered that the leak was due to evaporation of the plant’s acid storage ponds, exacerbated by drought and Ukraine’s closure of the North-Crimean canal, which had supplied water to the site. Meanwhile, social media warriors argued that the incident was intentional, and part of an information campaign to help destabilise the south of Ukraine’s Kherson region, which abuts Crimea.

It was a toxic situation, with denials, disinformation and cover-up feeding a social media frenzy. Two weeks later children were briefly evacuated from Armyansk as emissions continued, and the plant was temporarily closed. Suspicion had increasingly turned to the plant itself, and a production failure resulting from a culture of poor oversight and a corrupt relationship between the plant’s owner – a pro-Russian Ukrainian oligarch – and the Crimean authorities.

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the Ukrainian military began air quality monitoring on the Kherson border shortly after the incident began but a more comprehensive desk analysis of its cause was not undertaken until November. The analysis was unable to confirm whether the emissions were from the plant or the storage ponds, suggesting it may have been a combination of both. Each cause had a political implication for each side. Cooling pond evaporation would allow the Russian-backed authorities to blame Ukraine for cutting off the water supplies. A plant failure would allow Ukraine to blame the Crimean authorities. Irrespective of this blame game, the failure of the Crimean authorities and their backers to adequately respond to the incident unnecessarily impacted the people of Armyansk. Similarly, the lack of transparency appears to have facilitated the spread of fake news on social and in traditional media.

Case 2: That time the Houthis didn’t scuttle the oil tankers

In March 2018, Saudi Arabia’s Ambassador to Yemen tweeted a dire warning: “…the Houthis are planning to target the 19 ships in one place to destroy them, which will trigger an environmental disaster in the Red Sea”. He claimed that the Houthis had captured oil tankers and were holding them outside the port of Hodeidah. The planned scuttling would be the most extreme of the acts they allegedly had planned for the vessels, with the Ambassador suggesting that the plans would begin with ransoms of up to US$1m. He argued that these acts would fit well with the Houthis’ pattern of behaviour over the port.

The Ambassador may not have considered that the transponders on vessels allow their movements to be tracked with ease, particularly when combined with satellite imagery. And so it was that TankerTrackers.com – an independent online service that tracks and reports shipments and storage of crude oil – was able to rapidly challenge his claims through the use of open source data. They checked the vessels in the area, which seemed to be moving, with other vessels inbound: “Evidently, there are two more full tankers en route to Houdaydah. One of them departed just two days ago from Oman. Why would they be doing that? We haven’t seen any tankers surrounded or blocked.” Indeed, a week after the news of the possible impounding broke, the fleet had swollen to 31 vessels, with a number of tankers unloading normally during the period: no environmental damage was reported.

Case 3: That time when Ukraine’s Siversky Donets river wasn’t contaminated but could have been

In August 2018, documents were released by the hacking group CyberBerkut claiming that US secret services were helping Kyiv poison water supplies in eastern Ukraine. According to the documents, US instructors were training a Ukrainian military unit to dump nuclear waste into the water supply of areas not controlled by the Ukrainian government. According to the hackers, the “training was taking place at a base in Berdychiv, in central Ukraine, under the supervision of Blackwater founder Eric Prince.” The story was picked up by numerous Russian media outlets and reflected upon by Kyiv-based commentators.

The documents claimed that the saboteurs planned to contaminate the Siversky Donets – Donbas canal which, incidentally, also supplies water to large areas under Ukraine’s control too. One of the “leaked” documents detailed how the nuclear waste was transferred from Ukraine’s Vakelenchuk storage facility in March 2018, but, as was immediately pointed out by the website StopFake, this facility was decommissioned in 2017 and all the nuclear waste was removed. It was also alleged that, following the deliberate contamination, a broad information campaign spearheaded by international NGOs would be unleashed against the de-facto authorities in Donetsk and Luhansk, as well as against Russia, to blame them of incompetence, the inability to protect their people, and a breach of international law. Needless to say, to date, no poisoning has occurred.

Interestingly, several months before in April 2018, the de-facto authorities in Donetsk announced that they would stop pumping water out of the abandoned Yunkom coal mine in Yenakievo. The mine contains the byproducts of a Soviet experimental nuclear explosion in 1979. As far as is known, and that is relatively little, the radioactive material in the mine is currently firmly sealed as a result of the initial explosion. It is, however, rather difficult to precisely say how the rising water level will eventually affect it.

The Donetsk authorities have claimed that their own experts in the field, and those provided by Russia, have reliably assessed the risks of radioactive pollution from the flooded mine as being non-existent. But could the release of what overwhelmingly looks like a well-prepared piece of fake news have been a pre-emptive measure, in case something after all did go wrong? By the end of 2018, nearly a third of the Yunkom mine’s depth was flooded, as opposed to 7% at the beginning of the year.

Does the manipulation of environmental information matter?

There is a school of thought that views environmental issues as comparatively non-political in the context of conflicts. This is particularly true for problems that encompass large geographical areas or cross contested boundaries, or those whose effects may endure beyond the end of hostilities. Yet the examples above confirm that the opposite can often be the case. Environmental damage, or the fear of it, can be another toxic component of information warfare.

The complexity of de-escalating conflicts, and building and sustaining peace, means that the international community needs all the tools at its disposal to do so. Environmental cooperation over common risks has the potential to be a powerful vehicle for peacebuilding but this is contingent on building trust between parties. Weaponising environmental information, or allowing it to become so, makes building trust more difficult. The practice also has implications for the protection of people and ecosystems. Deliberate disinformation, or the sensationalising of information, can serve as a distraction that slows or confuses responses to harm. It can undermine the credibility of future warnings or, by promoting simplistic narratives, obscure more complex but no less important relationships that degrade the environment and contribute to human suffering during conflicts.

The growth of online communication, the rapid expansion of social media, and the fake news era it has ushered in, appear to have supercharged the political use of environmental information – and disinformation – during conflicts. Which begs the question: will it get worse? Broadly in line with Newton’s third law, there has been a reactive growth of individuals and organisations focused on challenging claims. But is this a solution on its own? It’s certainly necessary, but does it also increase the polarisation of the debate? In many cases, by the time claims have been challenged, it may be too late to persuade observers of the truth: claims that take seconds to make may take many hours of research to repudiate.

Disarming environmental information

The increasing extent to which environmental information is being weaponised in conflict settings presents challenges on a number of levels. Most fundamentally, inaccurate or misleading information becomes yet another weapon in “this twittering world” of digital propaganda warfare. By polarising debate and building mistrust it can prevent the utilisation of the environment as a tool for cooperation and building peace. And, when distortions slowly become accepted as fact, they can be followed by misguided policy-making and responses, detracting from the measures necessary to mitigate environmental risks and protect civilians.

The ultimate solution to these distortions is objective information, coupled with the promotion of dialogue about environmental risks. The questions we face are how information can be gathered and disseminated more quickly, how the number of actors collecting it can be increased, and how it can best be utilised to support environmental dialogue. It should of course be noted that information and dialogue alone is not a silver bullet. As the current case over the threat of an oil spill in Yemen demonstrates, environmental risks do not exist in a vacuum and many other factors influence the likelihood of whether parties to a conflict and other actors will take action to mitigate them.

Nevertheless, there is scope for the international architecture for the collection of objective environmental information to be improved. Deeper collaboration between NGOs, UN Environment and academia, and more effective cooperation with civil society and experts in conflict-affected states, could help plug the current gaps in coverage of the environmental dimensions of conflicts. There are an increasing number of remote and local data collection methodologies that can help provide temporary replacements for national monitoring systems, support them where coverage is inadequate, or create them where they are absent. A wide range of stakeholders – from indigenous peoples to affected communities and militaries, civil protection and demining specialists, local and NGO professionals on all sides of the conflict, and people displaced from conflict zones – may all have data or perspectives that are not currently integrated into efforts to document and verify environmental harm. Finally, we must become more adept at using the same tools that are facilitating environmental disinformation to challenge it.

A concerted effort to address the weaponisation of environmental information would also confer other benefits. It would help raise the profile of the environmental consequences of conflicts and improve responses. It would help inform more effective policy-making. And it could ultimately help reduce harm by increasing transparency and accountability. In that respect, the only thing we have to lose is the information war itself.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director, Dr Nickolai Denisov is a Senior Associate at Zoï Environment Network.