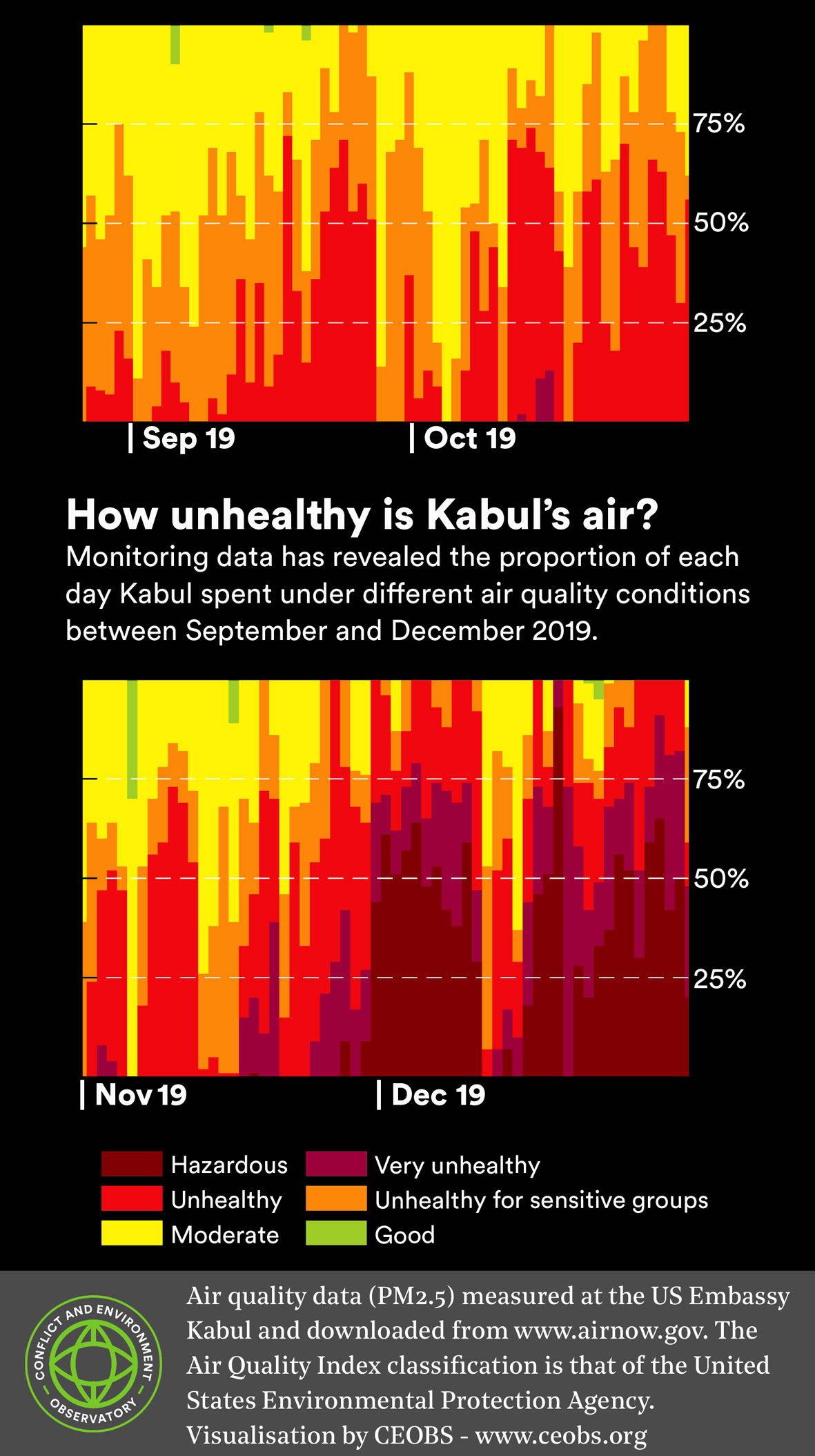

Between September and December 2019, a monitoring station in Kabul classed its air quality as good just 0.5% of the time.

Our analysis of air monitoring data recorded by the US embassy in Kabul has revealed that the city’s residents may have spent most of the autumn and winter breathing dangerously polluted air. It is thought that pollution in Afghanistan kills more people each year than armed violence.

Persistently poor air quality leads to surge in hospital cases

Over the last four months of 2019, and based on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s standards, the embassy data reveals that the air at the Kabul site was classed as “good” for just 0.5% of the time. Only for 30% of the time was the air quality satisfactory for those with pre-existing health conditions. Air quality deteriorated sharply in December, when 20% of the time was spent in “unhealthy” conditions, a further 20% in “very unhealthy” conditions and, concerningly, 40% in “hazardous” conditions – the highest pollution classification, and which represents an emergency situation with the entire population likely to be affected.

At the end of December, Afghanistan’s health ministry reported that 17 people had died of respiratory infections during the final week of 2019, and linked these to the hazardous pollution levels. The same week had also seen more than 8,800 patients visit government hospitals with health conditions connected to poor air quality.

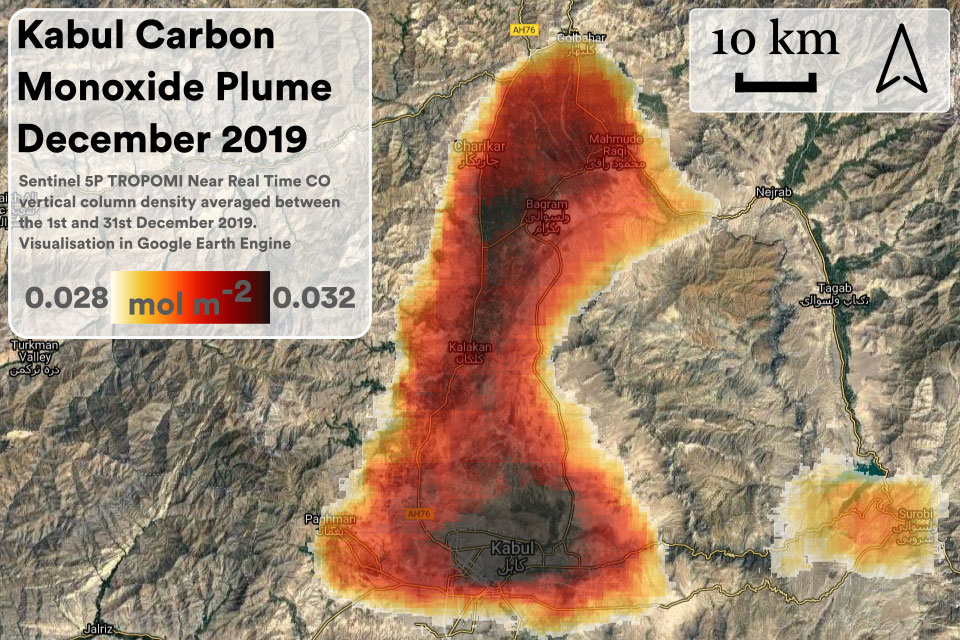

The US embassy is located in a relatively open and leafy part of central Kabul and thus may even experience better air quality than the more crowded and bustling residential areas. It is difficult to characterise the magnitude of the problem from just one site, especially when only one pollutant is measured (particulate matter, PM2.5). However, from satellite remote sensing (see below) we know that the pollution plume covers the entirety of the Kabul basin, home to over five million people. The basin also includes lots of agricultural land and crops may be damaged as pollutants are deposited, or there is damage from high ozone concentrations.

The root of the problem

But why is Kabul so notorious for poor air quality? The city lies in a valley, which reduces the mixing of air, particularly in winter when temperature inversions regularly form and prevent venting of pollution. There is little rain to remove the pollution from the atmosphere and so it accumulates during winter. Winters also see an upsurge in domestic fuel use. Manmade air pollution sources include leaded and poor quality fuels in vehicles and domestic generators, light industrial sources, and the burning of waste, plastics, coal, used oil and rubber.

Viewed from above the effect of Kabul’s geography is clear with its bowl trapping pollutants, here illustrated by the average carbon monoxide concentrations in December as measured from space.

In spring, snowmelt and rainfall transport soil and water often contaminated with human and industrial wastes into the basin – in the hot summer months this is dried and ground into fine dust, which is then resuspended into the air by wind and moving traffic. Notably, and in contrast to other cities in the region like Delhi and Lahore, our analysis of fire hotspot data shows crop burning does not contribute to the deterioration of air quality in winter. Over the three decades the city’s air quality problems have been further exacerbated by rapid and unplanned population growth. This has included populations displaced by the fighting in the country, and returning refugees who had left earlier.

The Afghan National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA) has been seeking to crack down on particularly problematic sources of air pollution. This month this has included the furnaces for tower blocks and closing down businesses. NEPA has also started publishing air quality data on its website on a weekly basis and using the campaigning hashtag #BeatKabulAirPollution.

The issue has been discussed by the parliament’s lower house, and NEPA has also set up a Whatsapp hotline for people in Kabul to report violations.

Unlikely to be solved soon

Even with the government’s crackdown on pollution sources Kabul’s annual air pollution woes look unlikely to be resolved soon. A more detailed network of air quality sensors and a pollution forecast model would allow the authorities to identify the most effective policies and strategies for addressing different pollution sources. This should be coupled with enhanced health monitoring to help identify the true public health cost of the problem.

Analysis by CEOBS’ Researcher Dr Eoghan Darbyshire