Pollution is killing more people in Afghanistan than armed violence.

Since 2003, much of the discourse around the environment in Afghanistan has focused on the security aspects of illicit natural resource extraction and, increasingly resilience to climate change. Rather less attention has been focused on the health and environmental risks from pollution, yet new estimates indicate that it is killing thousands each year. This blog examines the pollution challenge faced by Afghanistan, and its efforts to address it.

The problem with Kabul’s air

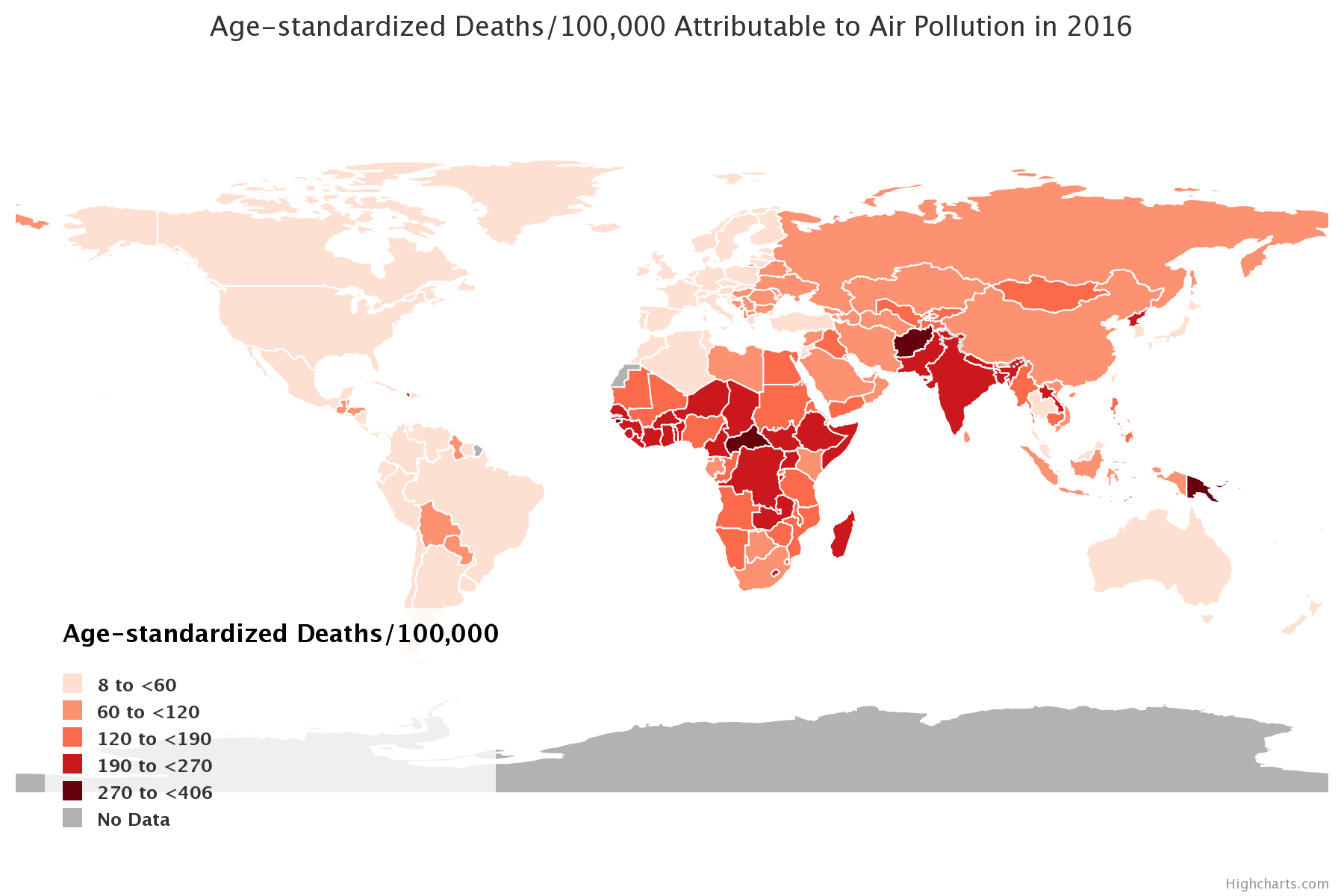

The latest report from the Health Effects Institute’s State of Global Air project estimates that air pollution was attributable for 51,600 deaths in Afghanistan in 2016. With an annual rate of 406 deaths per 100,000, its air pollution is among the worst in the world. The report combines data on PM2.5, ozone and indoor air pollution associated with the combustion of solid fuels.

That is a national estimate, but within Afghanistan it is Kabul that has become most notorious for poor air quality. While climatic and geographical factors play a role in influencing air movements in the city, these are exacerbated by high levels of manmade emissions. These include the use of leaded and poor quality fuels in vehicles and domestic generators, light industrial sources, and the burning of waste, plastics, coal and rubber. Other contributing factors are a combination of rapid population growth coupled with inadequate urban planning, and the limited provision of green spaces. The problem is particularly acute during the winter when residents rely on wood and coal for heating.

The State of Global Air report uses a range of sources to estimate the burden of air pollution. As with many developing countries, and countries affected by conflict, Afghanistan does not have a national air monitoring network. This places a high reliance on satellite data, national reporting and reviews of the scientific literature. Indeed other data held by the WHO’s Global Urban Ambient Air Pollution Database reveals that the most recent entry for Afghanistan is data from Kabul and Mazar-e Sharif that was provided by a Swedish military study in 2009 – it found very high levels of PM10 and moderately high levels of PM2.5. More recent data may be available from the US military’s Periodic Occupational and Environmental Monitoring (POEM) programme. Environmental monitoring of its bases in and around Kabul between 2003-15 suggested that some health problems could be expected from air pollution, even in previously fit personnel.

In spite of the data gaps, the Afghan authorities are aware of the problem and are seeking to address it. Dr Abdullah Abdullah, Chief Executive of the republic has convened a High Committee for the Prevention of Air Pollution, and in November 2017, Afghanistan’s National Environmental Protection Agency (NEPA) announced that air monitoring equipment had been purchased for the first time. However NEPA also criticised the failure of public and private institutions to implement measures to minimise pollution. Of particular concern were quarrying firms crushing rock around Kabul, and the city’s 700 artisanal brick furnaces.

The brick furnaces of the Deh Sabz District in the north of Kabul have come under scrutiny from UNICEF and the ILO in recent years. The majority of brick workers are children, who work in harsh conditions under a system of bonded labour; the primitive kilns, which run 365 days a year, burn a range of fuels, including coal, wood and car tyres. Kilns of this type occur worldwide but the sector’s emissions are poorly understood, in part because of the range of fuels used and the variation in kiln design. However it is thought that emissions may include sulphur oxides, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, forms of particulate matter including black carbon, and additional compounds released by the burning of coal and other fuels. While NEPA have stated that they will address the issue of pollution with kiln owners, given that they are routinely flouting recent laws barring the use of child labour on kilns, it seems questionable whether any reduction in emissions is likely.

Other initiatives to combat air pollution in Kabul include tighter vehicle emissions and a proposed green belt. Earlier this year the Directorate for Natural Resources announced a US$40m plan to allocate 10,000 hectares of land to new green spaces in Kabul, with additional projects for Kandahar and Herat. While residents have broadly welcomed the plans, many remain sceptical about whether they can be implemented due to corruption, and how much impact they can have on air quality without parallel measures to address the root causes of the problem.

Water pollution also a serious threat

In May, NEPA organised Afghanistan’s first ever conference on the effects of pollution on public health. Over two days, government ministers, parliamentarians, ambassadors, academics and civil society representatives sought to identify and begin to implement solutions to the pollution problems Afghanistan faces. Alongside the long-standing concerns over air quality, water pollution was also high on the agenda.

Heavily reliant on rainfall and snow melt for its rivers and the recharge of aquifers, Afghanistan is on the frontline of climate change and a trend towards lower and more variable precipitation in recent years is expected to strengthen as temperatures rise. This year’s drought conditions across the country may well be a sign of things to come. Speaking at the conference, the minister of state for natural disasters Najib Aqa Fahim reported that 80% of Afghanistan’s water is contaminated. For a country with a high reliance on agriculture, a rapidly growing population, and where drought conditions are common and water treatment infrastructure inadequate or wholly absent, water pollution is a serious threat.

In many areas, Afghanistan’s geological wealth contributes to often high levels of naturally occurring water pollution. Across the country, well and water body sampling has found high levels of arsenic, boron, fluoride and sulphate, but the security conditions have prevented efforts to comprehensively assess levels nationally.1 Levels risk being worsened in areas with high levels of mining activity, the majority of which is informal and unregulated. Alongside naturally occurring pollution, the three leading manmade sources of groundwater pollution in Afghanistan are agriculture, which contributes pesticides, nitrates and microbial contamination; poorly constructed domestic septic tanks, which contribute nitrates, viral and microbial contamination; and leachate from domestic and municipal wastes in informal unlined landfills.

Water pollution, and the limited access to improved water sources in Afghanistan, is thought to be a causal factor in high levels of child mortality and, while laws intended to reduce it are in place, their implementation is poor. This is due to a combination of factors, including weak security, limited monitoring capacity and the linked issues of high levels of illiteracy and low public awareness.

As with air pollution, Kabul typifies the water problems Afghanistan faces. And just as with air pollution, the causes are both natural and manmade. Kabul’s shallow aquifers do not receive enough rainfall to fully recharge, and the city’s rapidly expanding population, or at least those who can afford to dig their own wells, is being forced to bore ever deeper to reach water as the water table falls. The often seasonal Kabul River regularly dries up completely in the summer, at other times it is used for dumping waste and for the discharge of slurry from household septic tanks.

The city’s four water treatment plants are ineffective and barely cover half of the city’s population – many parts of the city’s water infrastructure had been destroyed or damaged by fighting by 2002. And, while industrial emissions are comparatively low, they remain weakly regulated and set to expand with Kabul’s growth. It is thought that around 80% of Kabul’s population rely on hand-pumped wells, with a similar number reliant on cesspits for sewage disposal. When combined with the low levels of aquifer recharge and flushing, the situation has led to very high levels of groundwater pollution: a survey in 2016 revealed faecal coliform contamination at 80% of the sites sampled.

Economic barriers to solid waste and chemicals management

Alongside Afghanistan’s air and water pollution, the country also faces severe issues with solid and hazardous waste management. Municipal waste management is underdeveloped in its major cities with an ongoing reliance on informal and unsanitary dumping; waste dumped in streets contributes to urban flooding, while areas with high levels of waste see increased rates of diarrhoea and respiratory infections. Leachate from unlined dumps is a factor in groundwater pollution. A 2015 review by UNHABITAT laid bare the enormous challenge facing municipalities in Afghanistan. Adequately dealing with Kabul’s annual 653,557 tons of waste would require 41% of the city’s entire budget; for some regional cities the cost would be two or three times their annual income. These financial barriers suggest that waste reduction at source and the expansion of recycling programmes may be the only viable solution at present.

Afghanistan’s limited economic resources are also an issue for its efforts to implement its national action plan for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Its plan, published in 2017, four years after accession to the convention highlights a number of sources of concern. These include the presence of ageing stocks of banned pesticides, oils containing PCBs in old and damaged electrical distribution equipment, and emissions of dioxins and furans from combustion processes. As with many other environmental issues facing the country, the plan suffered from a lack of quantitative environmental data, in part due to NEPA’s limited resources but also the access problems caused by the security situation. Resolving some of these issues – such as the threat from oils containing PCBs – will require significant international financial and technical assistance. The cost of PCB management alone is estimated at US$20m, while the installation of incinerators at hospitals to dispose of clinical waste without producing dioxins would cost US$50m.

Conflict’s legacy on environmental governance

Four decades of conflict and insecurity have had a grave impact on Afghanistan’s environment and, as a result, the health and livelihoods of its people. Since 2003 the country has benefitted from technical assistance from the international community to address environmental challenges. This support has created a national framework for environmental governance but the implementation of this framework continues to be constrained by a lack of resources, insecurity and corruption. The recent high level conferences on air and water pollution, new proposals for municipal level waste management strategies, and the action plans on POPs all serve to demonstrate governmental attention but the gap between these plans and change on the ground remains stark.

The Asia Foundation has been conducting surveys on the national mood of Afghanistan since 2006. Its 2017 survey found growing if cautious optimism for Afghanistan’s future – in spite of high levels of armed violence during the 2016 study period. The chief concerns among interviewees in 2016 were insecurity and unemployment. Just 3% of those polled on their local concerns raised the issue of pollution, although far more highlighted access to drinking water as problem, particularly in Kabul. This represented a modest increase on data collected in 2015 for 2016’s survey but participants’ concerns over a range of environmental issues remain comparatively low.

Addressing Afghanistan’s pollution problems in the face of its ongoing insecurity is a huge challenge. As with many other conflict-affected states, the linkages between conflict, development and pollution are readily apparent but solving these issues requires actions by all sections of society, from the individual to the governmental level – a tall order when both are fighting for their day to day survival. Yet if the estimates are correct, the slow harm of pollution in Afghanistan is killing and sickening more people each year than are directly harmed by armed violence in the country. If this is indeed the case, reducing its burden on health and the environment must be made a greater priority for the government and international community.

Doug Weir is the Research and Policy Director at The Conflict and Environment Observatory.

- Hayat, E. & Baba, A. Environ Monit Assess (2017) 189: 318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-017-6032-1