Can we improve the environmental outcomes of mine clearance operations?

In this piece, Linsey Cottrell and Kendra Dupuy provide an overview of the relationship between humanitarian mine action and the environment, examining both how mines and mine action can impact the environment, and how environmental change can influence mine action.

Banned but still with us

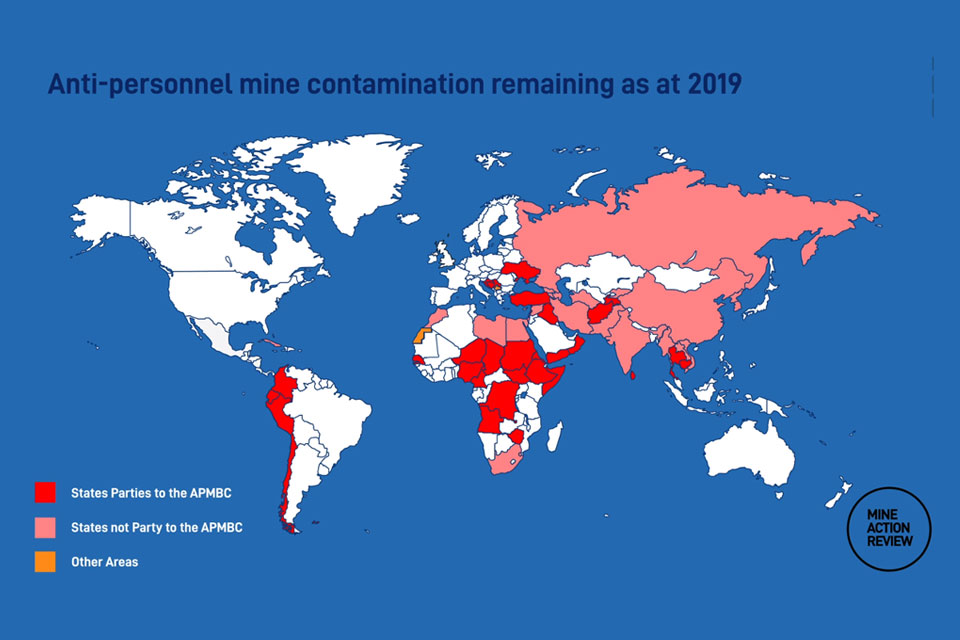

The late Princess Diana’s involvement with the work of the HALO Trust did much to highlight the issue of anti-personnel landmines. The Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention is a disarmament treaty which was adopted after Princess Diana’s death in 1997 and came into force in 1999. The treaty includes a commitment for state parties to not develop, produce, acquire, stockpile or use anti-personnel mines and to ensure that mined areas within their territory are cleared. The treaty has been signed by more than 80 per cent of the world’s countries, but China, Russia and the USA are among those countries that have not signed.

With more than 60 million people estimated to be living in areas affected by landmines, and the increased use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in recent conflicts, the risks facing communities 20 years after the Treaty was signed are still prevalent. Explosive remnants of war (ERW) include landmines and cluster munitions (which are dropped by aircraft or fired from ground level and open mid-air to release multiple submunitions). They can remain in the ground for decades and prevent a community’s safe access to land and therefore local resources. Humanitarian demining operators remove ERW to make the area safe for people to use and include organisations such as Norwegian People’s Aid (NPA), the Mines Advisory Group (MAG) and The HALO Trust. They all operate globally and have been implementing mine clearance programmes for more than 25 years.

Consequences for the environment

Humanitarian demining is not without risk of environmental harm, and this is acknowledged by work carried out by the United Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), the Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) and mine action operators such as NPA on the development of international mine action standards. However, the current International Mine Action Standards (IMAS), developed as a framework to guide national authorities and operators alike, do not incorporate specific practical measures to minimise potential environmental impacts.

Most national authorities in countries dealing with the legacy of landmines and ERW have not yet introduced a national standard to incorporate environmental management, and many of these countries also do not always have strong environmental legislation or governance in place.

Mine clearance activities may involve the clearance of vegetation, the use and deployment of heavy machinery, the detonation or disposal of large quantities of explosives and the generation of hazardous and non-hazardous waste – all of which has the potential to result in adverse environmental effects if not properly managed. This is also true of how land is used following the clearance of landmines. Where there is a severe threat to people, from injury or death from unexploded ordnance, it can be more difficult to relay the importance and relevance of the potential environmental effects of landmine clearance, even though these may have long-term significance.

Prioritising the environment

In light of budgetary, logistical and sometimes ongoing security constraints, environmental management and mitigation has not always been a priority. Moves to improve this are gaining momentum within humanitarian demining work, as well as action across other the wider humanitarian aid sector. At this year’s annual National Mine Action Director’s meeting at the UN, the environment was highlighted and there were positive discussions about what is already being done and what more can be done to improve environmental performance across the sector.

For the wider humanitarian sector, the UN established the Environment and Humanitarian Action (EHA) network in 2014, with the aim of promoting environmentally responsible humanitarian programmes. Organisations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross have been working to embed environmental practices in their operations and have already launched a Green Response Strategic Plan. However, research in 2019–20 by students from the London School of Economics suggests that many humanitarian organisations have yet to develop and implement environmental policies for their humanitarian aid and field work. Factors limiting progress include the availability of resources, expertise and funding.

Regional challenges

The potential environmental impacts relating to demining activities, and their significance, varies with the region affected and the specific legacy of ERW involved. In Libya, for example, the long history of armed conflict has left numerous large ammunition stockpiles, landmines and unexploded ordnance. Missiles procured by the former Libyan regime also used highly hazardous liquid propellent fuels (such as unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine) and chemical oxidisers (such as red fuming nitric acid), which pose significant safety and environmental risks. Appropriate handling and disposal of these hazardous liquids during mine action, in an environmental acceptable manner, is critical to ensure protection for the demining teams, local populations and the wider environment, especially given Libya’s high reliance on groundwater resources.

Cambodia is regarded as one of the countries most heavily contaminated by cluster munitions, the result of heavy bombing by the USA during the USA–Vietnam War and its targeting of the Viet Cong’s supply lines. The UN Development Programme (UNDP) completed an environmental and social impact assessment in 2016, which highlighted the important role of the clearance of cluster munitions in supporting economic growth for the country. However, Cambodia has also experienced high rates of deforestation, with an estimated 27 per cent decline in tree cover since 2000.

One of the areas in Cambodia most heavily contaminated by landmines is the K5 mine belt, located in the north-west along the Cambodian–Thai border. The K5 belt was laid with mines in the mid-1980s as part of a Cambodian defence plan to prevent the Khmer Rouge militia returning from Thailand, back into Cambodia. Creating the K5 belt required the clearing of tropical forest to create an open space approximately 500 m wide and 700 km in length. After almost 40 years, the tropical undergrowth has re-established, so areas like the K5 mine belt are regarded as ‘crucial to maintaining biological corridors between transboundary protected areas and remain some of the last forested tracts in areas of high agricultural encroachment and rapid deforestation’.

Internal migration, increased settlement and greater demand for agricultural land have already accelerated rates of deforestation close to the Cambodian–Thai border and K5 mine belt. People in low-income communities often have little choice other than to risk their lives to earn a living from land known or suspected to be contaminated by landmines. With people prepared to take such risks by either cultivating or foraging within mine-contaminated land or forest, demining operations are critical to protect local people. The clearance of mines and release of land could, however, lead to other unintended environmental consequences by improving access to forests and potentially increasing deforestation rates.

Countries such as Angola, Colombia, Myanmar and Vietnam, where humanitarian demining is taking place, have also experienced high rates of deforestation in recent years. Long-term planning is required to ensure that demining operations do not attract people and economic development into areas that were previously sparsely populated, as this would potentially increase deforestation and vegetation clearance and adversely affect local biodiversity in post-clearance areas.

Humanitarian demining in Colombia is often cited as an example of good environmental practice, with the Colombian Mine Action Authority (Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz – Descontamina Colombia [OACP-DC]) and the Swiss Foundation for Mine Action (FSD) working together to develop tools and specific environmental advice. This is especially important for a country that is so rich in biodiversity but suffers from the threats of deforestation and illegal logging. The Colombian government stipulates a requirement for compensatory planting in areas where vegetation clearance cannot be avoided, reduced or mitigated during demining work but, to date, there is no guidance on what is meant by compensatory planting or how it should be done.

Tree or compensatory planting are not normal day-to-day activities for demining operators or their area of expertise. Where planting is needed or recommended to offset negative effects from demining activities or to enhance the environment, guidance from and partnerships with local organisations active in reforestation or planting initiatives are needed. This would ensure an approach based on the right tree in the right place, with informed species selection, community consultation and management planning. Compensatory planting could then establish properly and contribute positively to the environment.

Open burning and open detonation

Despite obvious costs and logistical constraints, the humanitarian mine action sector must also seek to ensure that all practical and responsible efforts are in place to minimise the environmental impact from the disposal and destruction of munitions. The residual soil and water contamination at military ranges caused by the firing, detonation and disposal of munitions by open burning and open detonation (OBOD) is well documented, and there has been increased attention on finding more environmentally acceptable options.

Within the military sector, OBOD has come under increased scrutiny due to environmental concerns, with a view to further reducing and eliminating its use. Although OBOD of waste explosives is banned in countries such as Canada, Germany and the Netherlands (unless there is no other means) and discouraged in others, it remains in use in many regions since it is cost effective and does not require sophisticated infrastructure and equipment. This is particularly the case in developing and conflict-affected states, or where expedient destruction is needed for the disposal of unsafe items; often no other practical option is available.

For the humanitarian sector, disposal options must remain cost effective and practical. Alternatives to OBOD, such as explosives harvesting or chemical treatment/neutralisation, may be viable but we need to understand their feasibility and how they may need to be adapted to meet needs within the humanitarian sector. Techniques developed include the conversion of explosives into non-energetic by-products, such as fertilisers, which could be sold to generate revenue. This would be subject to the quality assurance of any products (eg checking residual heavy metal content).

As well as good environmental performance, munition disposal options must be economically viable and consider a range of factors, such as the state and type of munition, the amount to be disposed of, local staff training and competencies, consistency with international agreements and alignment with any applicable national safety, security and environmental regulations. The United States Environmental Protection Agency recently undertook a review of the alternatives to OBOD, and further research into viable alternatives to OBOD and mitigation practices for the humanitarian sector is required.

Climate change and mine action

To date, the IMAS do not yet provide guidance on how climate change may affect mine action, or the potential need for climate change adaptation planning. Climate change may potentially impact local humanitarian mine action activities in a number of ways.

Back in 2014, for example, heavy rain and flooding across parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina resulted in more than 3,000 landslides. These made the records of the location of minefields unreliable, requiring reassessment. Other countries where flooding or landslides have been reported to have affected mine clearance activities include Angola, Iraq, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (PDR), Sudan and Zimbabwe. For Lao PDR, which remains the world’s most heavily contaminated country by cluster munitions, news reports cited the risk that severe tropical storms and flooding in 2018 had caused explosive items to move. In the future, areas previously considered as a low priority for survey and clearance may now need to be re-prioritised or targeted if they are more vulnerable to climate change. This includes coastal locations, river banks or areas with steep slopes, all of which may become more technically challenging and costly to clear.

Intense rainfall can also halt or hinder clearance programmes, due to restricting access or by limiting the use of machinery or mine-detection dogs, which are unable to work in wet conditions. In the long term, the impact from future population movements and climate refugees may also require consideration in mine clearance because of increasing pressures on land use.

Higher summer temperatures could also adversely affect the management of munition stockpiles. Munitions are designed to withstand intense heat in the short term, but prolonged high temperatures and humidity can destabilise them, weaken their structural integrity, damage seals and increase the risk of explosion. Tidal surges and warmer sea temperatures due to climate change may also increase risks from the legacy of marine-dumped ordnance, and will require consideration by specialist underwater clearance teams.

Sector-wide challenges

Even though the sector is highly specialised and usually operates in very difficult environments, many of the challenges ahead are not unique to humanitarian demining, so lessons can be learned from elsewhere. Similarly, humanitarian demining organisations already have a strong track record in training and building up local workforce capacity. This is something that will be important in developing stronger environmental practices and working partnerships with local environmental NGOs and communities.

It is important that resourcing is available to support environmental planning and implementation within the sector, with mandatory environmental training, awareness raising and the implementation of data-collection systems for environmental management. Unless there is monitoring, as with any management system, measures to control and manage environmental impacts cannot be properly assessed. These can then be used to develop long-term indicators to monitor performance improvements and register the benefits achieved.

The humanitarian demining sector reports a current funding shortfall of approximately US$1 billion – only 0.4 per cent of overseas aid is allocated to mine action. Another priority and challenge will be to address preconceptions that meeting higher environmental performance will lead to higher costs. Some donors already require environmental impact assessments to be carried out, or at least evidence that environmental commitments are in place. But donors should also accept that resources should be made available to achieve these.

In countries where there is already a struggle to meet even the most basic needs of the population, the management of the environment will often be regarded as a lower priority. However, the two aspects must not be viewed as either/or: done well, environmentally sensitive demining can further benefit the health, livelihoods and climate resilience of communities, as well as protecting ecosystems.

Linsey Cottrell is CEOBS’ Environmental Policy Officer and Kendra Dupuy is Senior Environmental Advisor at Norwegian People’s Aid. The blog was first published by the Institution of Environmental Sciences.

Further reading

- Loughran, C. (2019) The Mine Ban Convention, Article 5 & 2019 Review Conference: need for urgent action

- Schwartzstein, P. (2019) Climate Change May Be Blowing Up Arms Depots

- Zhou, W. and Raab, A. (2019) IEDs and the Mine Ban Convention: a minefield of definitions