Monitoring environmental risks and damage during conflicts is vital, the case of Ukraine highlights how it can be improved.

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine is thought to have caused serious damage to the environment, and with it risks to human health, in what is a highly industrialised region. Since 2015, a number of different actors have published data on the environmental impact of the conflict. In this blog, Doug Weir and Nickolai Denisov take a look at the different methodologies that have been used by organisations to monitor environmental harm during the conflict, their findings, and what the studies from Ukraine tell us about how this work could be improved.

Why monitoring is vital

Armed conflicts damage the environment in a number of ways; harm can be direct – caused by the conduct of hostilities, or indirect, as a result of the conditions associated with conflicts and insecurity. Environmental damage can harm both ecosystems and human health, so documenting damage is vital to protect civilians and to inform response and recovery. It is also a critical component of encouraging accountability for harmful acts, for changing the most environmentally damaging behaviours and as a basis for environmental cooperation.

Comprehensive assessments of the environmental impact of conflicts can only take place after the fighting has ended. However in recent years, there have been increased efforts to collect data on harm during conflicts. As post-conflict assessments may only be able to identify the environmental conditions at the time of the assessment, they are unable to fully record changes over time, or ephemeral problems such as changes in air quality or water pollution, which may nevertheless have detrimental effects on human health and the environment. Monitoring during conflicts can record these short-term events and help identify areas of concern for later studies. It can also provide the data necessary for urgent humanitarian and environmental measures to minimise harm. Moreover, by helping to raise awareness of the environmental dimensions of conflicts as they are fought, it can also help to create the political space to allow comprehensive assessments in their wake.

This blog uses the example of the conflict in eastern Ukraine to study how different actors have gathered environmental data during the conflict in the absence of a comprehensive assessment, and what this can tell us about how data could be collected and utilised in future.

The environmental consequences of the Ukraine conflict

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine’s Donbas region has caused a range of environmental problems. The majority of these are intertwined with the region’s history of intense industrialisation and mining. Issues of concern include: water pollution from flooded and abandoned coal mines; the risks of pollution incidents from sensitive industrial facilities and civilian infrastructure; pollution from the use of weapons; the management and disposal of debris; and the collapse of waste management and other environmental services. The region’s ecosystems and natural resources have also been affected, with agricultural areas degraded, and forests and protected areas damaged by felling, fires, mining, and military activities.

The first reports highlighting the environmental consequences of the conflict were published by civil society in 2015, by the Ukrainian NGO Environment-People-Law (EPL), and the Zoi Environment Network and Toxic Remnants of War Project. Since then, a number of other studies and materials, including some intended to support reconstruction activities, have been published by NGOs, and national and international organisations. Earlier this year, upon a request from the Ministry of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine, the OSCE launched a project called the Assessment of the Environmental Damage in eastern Ukraine. Supported by the governments of Canada and Austria, its aim was to conduct assessments and prepare recommendations for the region’s recovery. The project involved some limited sampling work but also included a meta-analysis of the research published to date by the various actors studying the conflict’s impact on the environment. Its findings were presented at a meeting at the end of November.

This meta-analysis provides a window on the developing field of environmental monitoring during conflicts, and the ecosystem of organisations engaged in this work. It is also an opportunity to review the different methodologies that have been employed, their limitations, the forms of damage that have been studied, and how the data collected has been presented and utilised.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TYPE OF ORGANISATION / PROCESS | ||||||||||||

| Intergovernmental | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Governmental | Y | |||||||||||

| Non-governmental | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| ANALYTICAL RESEARCH METHODS | ||||||||||||

| Overview of literature | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Analysis of traditional and social media | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Analysis of other organisations data | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Own field studies | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| PRIORITIES OF ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS | ||||||||||||

| General environmental situation | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| Direct impact of hostilities on the environment | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| Air | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Groundwater | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Surface waters | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| Soils, land resources | Y | Y | Y | |||||||||

| Forests | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| Flora, fauna and protected areas | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| Emergencies and industrial accidents | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||

| Water supply, waste disposal, waste | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||

| Environmental services in the conflict zone | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||||

| TYPES OF RECOMMENDATIONS AND PROPOSALS | ||||||||||||

| General and strategic | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| Informational | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||

| Legislative | Y | Y | ||||||||||

| Administration and organisational | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||||

| Engineering and technical | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| Foreign policy | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||||||

| AVAILABILITY OF RESULTS | ||||||||||||

| Publicly available on the Internet | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||||

| Restricted | Y | Y | Y | Y |

Key

1 – World Bank-EU-UN analysis and reconstruction programme (2015)

2 – NGO Environment-People-Law analysis (2015)

3 – NGO Zoï Environment Network/Toxic Remnants of War Project publications (2015 – 2017)

4 – Research for the Trilateral Contact Group (2015-2016)

5 – OSCE Special Monitoring Mission Report (2015)

6 – MTOT Draft of the governmental targeted reconstruction and peacebuilding programme (2016)1

7 – NGO Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (2017)

8 – NGO Bellingcat/PAX analysis (2017a 2017b)

9 – NGO Ukrainian Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (2017)

10 – UNICEF (2017)2

11 – UN OCHA (2017)

12 – OSCE Project Coordinator in Ukraine materials (2017)

Ecosystem analysis

The “ecosystem” of organisations that have recorded or published environmental data on the conflict is of interest. At the UN level, data was published by a partnership between the World Bank, EU, and UN (WB-EU-UN ) in 2015 in an early effort to formulate a preliminary set of reconstruction measures, including environmental recovery, once the conflict is over. In 2017, UN OCHA conducted specific research into industrial hazards, while UNICEF studied threats to water and sanitation, a topic also studied by the OSCE’s Special Monitoring Mission in 2015.

On the intergovernmental level, research into the sustainability of water supplies and the impact of mine closures was undertaken for the Trilateral Contact Group, which comprises Ukraine, Russia and the OSCE. The research was supported financially by Germany. While Ukraine’s Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories and Internally Displaced Persons (MTOT) and its Ministry of the Environment have collected information on the environmental impact of the conflict, and the respective recovery needs, directly from local authorities in the affected regions.

Of six civil society organisations that have published research, three specialise in conflicts, two could be viewed as environmental generalists, and one works primarily on human rights. Notably, two were Ukrainian NGOs, while the Geneva-based Zoi Environment Network had historically worked on environmental issues in the region, and their local knowledge and contacts facilitated the collection and interpretation of data.

Transparency

Of the 12 studies and sets of materials assessed, eight are freely available online, while the remainder are restricted. The latter include studies from UNICEF, UN OCHA, the Trilateral Contact Group and the Swiss-based international NGO the Henri Dunant Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (CHD). While this last study has not been made public, its findings have formed the basis of a number of media reports in both Russia and Ukraine.

The question of when to go public with data on environmental harm that may be speculative because the findings have not been supported by detailed field assessments is a persistent challenge. This is particularly so for data from conflict settings, where findings may be potentially controversial and easily politicised. In our view, and in spite of these factors, the default should be to publish and open up studies to external scrutiny, providing that they are published with the necessary caveats outlining their limitations.

As experience shows, withholding such information from the public is seldom justified; whereas its release will help raise awareness of the environmental dimension of a conflict, guide further fact-finding and inform eventual recovery planning. This also applies to all regular environmental monitoring data that reflect the environmental situation before and during the conflict, such as the results from the regular sampling of air and water quality, and which are held by various state and municipal authorities: without full unrestricted access to such data it is difficult to reveal trends and precisely determine the environmental impact of the conflict.

Data collection methodologies

More than half of the organisations in the review undertook their own field studies or data collection exercises. EPL, CHD and the OSCE carried out limited field sampling of chemical pollution in various media, including soils, surface and ground waters. The OSCE’s sampling was restricted to government-controlled areas. EPL and the Ukrainian Helsinki Foundation (UHF) visited protected areas to assess damage on-site, and collected information on them remotely. Meanwhile experts commissioned by the Trilateral Contact Group, UN OCHA and UNICEF visited a range of industrial facilities on both sides of the line of contact where the OSCE SMM also maintains a continuous presence. The MTOT collected data directly from local authorities in the government-controlled areas.

The EPL, CHD, UHF, UN OCHA and OSCE studies, and the WB-EU-UN reconstruction programme included reviews of publications or results that existed at the time; and most studies made extensive use of the governmental, municipal, industrial and international data that were available. EPL, Zoi, Bellingcat/PAX and the OSCE undertook original analysis of information from various sources, including monitoring data, satellite imagery and locally-sourced knowledge. EPL, Zoi, UHF, Bellingcat/PAX and the OSCE also made significant use of media reports, indeed traditional media reports made up part of the OSCE project’s database of accidents at industrial facilities, while Bellingcat/PAX was the only study to make wide use of information from social media.

What they found

Several general conclusions can be reached from the review of available studies and other publications on environmental issues in eastern Ukraine. Firstly, while the body of original data that is available – both field-based and analytical – is limited but diverse, collectively it already provides a rough, yet fairly consistent, picture of the environmental situation and impacts in the conflict area. Nevertheless, much more can and should be done to expand this dataset.

Secondly, due to the relative deficit of original data and analysis, the same information tends to be recycled repeatedly across the different studies, publications and media coverage, eventually losing its originality and traceability. Of the sources of these data, traditional media remains an important source of factual reporting, while the use of social media is underdeveloped, in part because it is often met with scepticism due to perceived reliability issues. Finally, for areas that have been rendered inaccessible due to security issues, including across the line of contact, local and expert knowledge remains an important source of information and judgement.

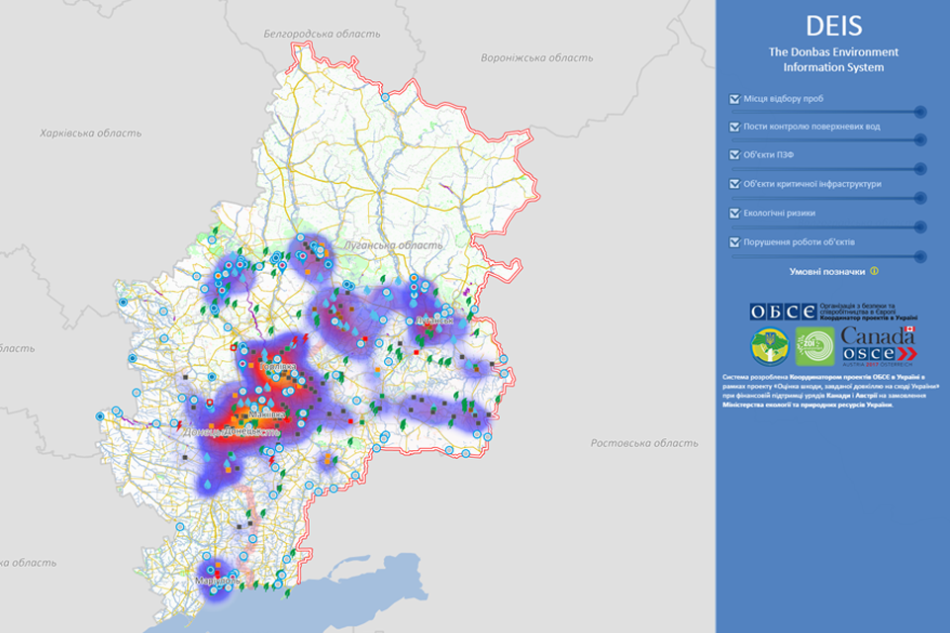

Screengrab from the online Donbas Environmental Information System, which was established as part of the OSCE’s latest project.

Accuracy and consistency

Some conclusions can also be drawn about the consistency of data and analysis on the severity of environmental impacts in the affected areas. Quite predictably, official government monitoring data provided only limited insights. Since the beginning of the conflict, the number of enterprises reporting to Ukraine’s State Statistical Service has dropped by 65%; including a reduction from 131 to 37 for reporting by large enterprises. Similarly, parts of the pre-war network for monitoring air and water quality have been lost or have scaled down their operation. Restoring the network, and complementing it with expert assessments of what is happening in pollution hotspots, will be vital for monitoring the environmental situation in detail. This has already been acknowledged and is being addressed by both state and local administrations in eastern Ukraine.

Considerable attention has justifiably been focused on the health and environmental risks posed by industrial facilities in the event of an accident caused by the conflict. Interestingly, this also led to the separatist authorities compiling a list of enterprises posing environmental risks in areas controlled by the Ukrainian government, and a call from them to conduct their own inspections. To our knowledge, this was not accepted by Ukraine, but the 2017 UN OCHA mission was able to visit selected facilities on both sides of the line of contact. The risks from industrial facilities and flooded mines have also been repeatedly addressed within the Trilateral Contact Group.

Although the OSCE expert assessment identified 75 industrial and 12 water supply facilities which need priority attention on both sides of the line of contact, opinions differ among experts and organisations about the actual likelihood of serious accidents. In our view, and in light of the significant potential for harm, a precautionary approach has been justified: sometimes it is necessary to credibly assume worst case scenarios, particularly if this encourages detailed studies and monitoring of high risk facilities, including reviews of their emergency response capacity.

As with other industrial risks, information about the coal and mercury mines that have been flooded in the conflict area due to electricity shortages and the termination of production has been sparse and divergent. The OSCE’s expert data – 36 mines flooded on both sides of the contact line – currently appear to be the most reliable, primarily because this makes use of local industrial expertise, as most of the mines cannot be accessed directly.

Finally, the early concerns about widespread pollution from the use of weapons may be somewhat exaggerated. The admittedly limited sampling by the OSCE found that on average, there was no significant difference between pollution with a variety of heavy metals in locations directly affected by hostilities, compared to locations where no fighting had taken place. A systematic difference of 10-30% was only observed for mercury, vanadium, cadmium, inactive strontium and gamma-radiation. However, as more intense pollution – at levels 10 to 100 times and more above background – was found by the OSCE, as well as in earlier studies by EPL and CHD, in selected areas strongly affected by the fighting, a larger-scale systematic sampling programme is necessary to confirm or refine these initial findings. Similarly, despite the two to three fold increase in forest and grass fires in combat areas that was observed in 2014, a more thorough analysis of satellite imagery and field data is needed to understand the full impact of hostilities on forests and vegetation.

How can environmental monitoring during conflicts be improved?

At September’s meeting of the UN Environment/OCHA Environment and Emergencies Forum, participants from UN, humanitarian, environmental and military research organisations discussed the developing field of environmental monitoring in conflict settings. It was clear that data collection was vital for informing humanitarian response but that further work was needed to develop and refine remote and field-based methodologies. Critically, there was also a pressing need for a more coherent model of data sharing between relevant organisations.

The analysis of the Ukraine conflict above highlights a number of areas that should be considered as part of this developing discussion. It was clear that local expert knowledge is important for both identifying data sources and providing context, and that partnerships should be developed between local and international actors early on in a conflict. There is also value in conducting targeted remote and field studies on environmentally sensitive industries and infrastructure, as well as on the direct chemical impact of the use of weapons. While the immediate civilian risks from such sites will inevitably see them prioritised, this should not preclude assessments of the natural environment, such as soils, forests and protected areas.

Government authorities in affected areas should endeavour to open access to all existing monitoring data to allow its systematic analysis, and more effective systems of cooperation are needed on data collection among humanitarian actors, such as those working on water and sanitation or mine action, and the military. There should also be a greater focus on restoring official monitoring systems impacted by conflicts or introducing mobile systems. The gaps in statistical reporting that appear should be filled with expert assessments to allow some temporal comparisons to be made. In addition, greater use should be made of open source data and information from social media.

Finally, all actors, be they governments, international organisations or NGOs, should collaborate more efficiently to institutionalise the objective of data sharing and publication, both within and beyond their own community. Doing so would allow more effective shared analysis of data, help publicise the environmental consequences of the conflict and encourage further data collection, and facilitate environmental cooperation between conflict parties in support of environmental assessment and recovery. The potential for community-led environmental sampling and assessment methodologies should also be explored in this context.

What’s at stake?

Environmental protection has historically been considered as a low priority in conflict settings. There is an assumption that collateral damage will occur, and that it is unavoidable. And this acceptance of environmental harm as an outcome of warfare has to a certain extent been reinforced by the existing model of UN-led post-conflict environmental assessments. Comprehensive and impartial assessments are a vital part of the recovery process but they also risk delaying attention on the environmental causes and consequences of conflicts.

There are many forms of environmental harm that can have direct and serious consequences for the civilian population and ecosystems, and occasions where urgent action is needed to mitigate these risks during conflicts. The potential threat posed by an accidental release of chlorine from the Donetsk Water Filtration Plant in Ukraine is a case in point. In early November 2017, a reserve pipeline for supplying the plant with chlorine was damaged by shelling. It had also suffered damage in January 2015 and February 2017. Had the line been in use on these occasions, there would have been consequences for human health and the environment. The site is just one of many hazardous installations in the conflict area and a reminder of why precaution is justified. Cooperation between civil society and international organisations can help to identify and address these risks, and also ensure that an environmental narrative is present in the coverage of conflicts.

Data collection during conflicts can also provide opportunities for dialogue between warring parties. Again in the case of Ukraine, there appears to be a growing appetite for cooperation on common environmental risks caused by the conflict between civil society organisations and local administrations on both sides of the line of contact. These are opportunities that may be missed by delaying environmental data collection until conflicts are over.

Developing and promoting environmental narratives for conflicts is also vital to inform policy change. The negotiations on recent resolutions on conflict and the environment at UNEA-2 and UNEA-3 were informed by data made available by UN Environment and civil society, and it played a key role in framing the context and the content of the resolutions. With debates on environmental security and the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts ongoing in the UN Security Council and the General Assembly, there has rarely been a more important time to expand and refine our data collection activities.

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project; Nickolai Denisov is a Regional Director at Zoi Environment Network.

- The programme is not an analytical document, but provides an insight into government priorities.

- Analysis by description on the implementing organisation’s web-site www.pap.co.at: Risk Assessment of Voda Donbassa Water Supply Services in Donetsk Oblast of Ukraine.