Is South Sudan’s Sudd wetland at a fork in the road?

Published: November, 2021 · Categories: Publications, South Sudan

A view of the Sudd wetlands from the International Space Station, January 2021. Photo ID: ISS064-E-19351

Introduction

The Sudd wetland is one of the most unique and valuable ecosystems on Earth. It is the largest wetland in Africa, a designated a Ramsar site, and supports endangered mammalian species, rich and abundant fish populations, and around 1 million people whose livelihoods are attuned to the changes in the environment – particularly through cattle herding. The Sudd wetlands are of critical importance to South Sudan and the wider region through two competing factors – the value of the oil below them, and the important ecosystem services they currently provide.

To date, this relationship between oil and water has been catastrophic for the country and for the wetlands. This is laid bare in the recent September 2021 Human Rights Council paper on ‘Human rights violations and related economic crimes’. This reveals and documents how political leaders have systematically and illicitly diverted staggering sums from the public coffers, in part by a highly informal system of oil revenue collection. The same findings were also outlined in an independent report by Crisis Group in October. Unaccountable oil consortia and their political counterparts have wrought considerable environmental degradation to the Sudd, particularly via crude oil contamination of the wetlands, with severe consequences for the health of communities. This situation has arisen because of, and feeds into, conflict in South Sudan.

South Sudan’s totemic Sudd wetlands are at a fork in the road. Down one path lies further oil exploration and drainage for hydropolitical gain. Down the other path is preservation, keeping oil in the ground for peace, and for the full capitalisation of the ecosystem services the wetland can provide, protecting livelihoods against climate change. Now is the time for governmental decisions on which path to take, and this will be heavily influenced by the type of support and incentives offered by international donors.

Down either path lies uncertainty – there is simply a huge knowledge gap when it comes to the Sudd, and it is critical there are now further observations and research into its hydrology, into the damage from oil production and into the Sudd’s role in flood prevention, its modulation of the regional climate, and as a carbon source or sink.

In this report we explore these two pathways in more detail and the accompanying knowledge gaps. In an accompanying article we investigate how the seasonal extent of the Sudd is – or isn’t – linked to pastoralist conflict.

Key findings

- Oil pollution has continued as production has resumed following the civil war. Pollution may have recently been exacerbated by catastrophic flooding, potentially dispersing contaminated water across the landscape and into settlements.

- A recent licensing round and renewed activity around new pipelines indicates oil, and its associated conflict and environmental ills, may dominate the landscape for decades to come. Given the relatively small revenues versus the damage wrought, we recommend further exploration of Crisis Group’s recent suggestion that international donors pay to keep oil in the ground.

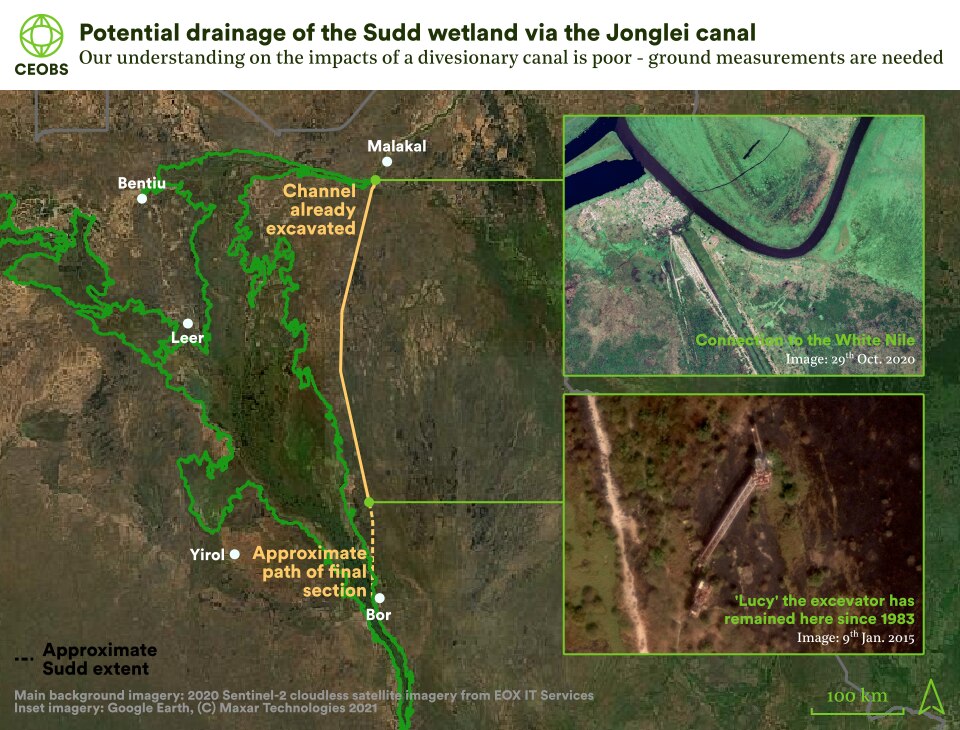

- There are moves to resume construction of the Jonglei canal, to drain the Sudd for regional hydro-political gain. This is an existential risk because not enough is known about the region’s hydrology to do so. Field research is required to inform state of the art hydrological modelling.

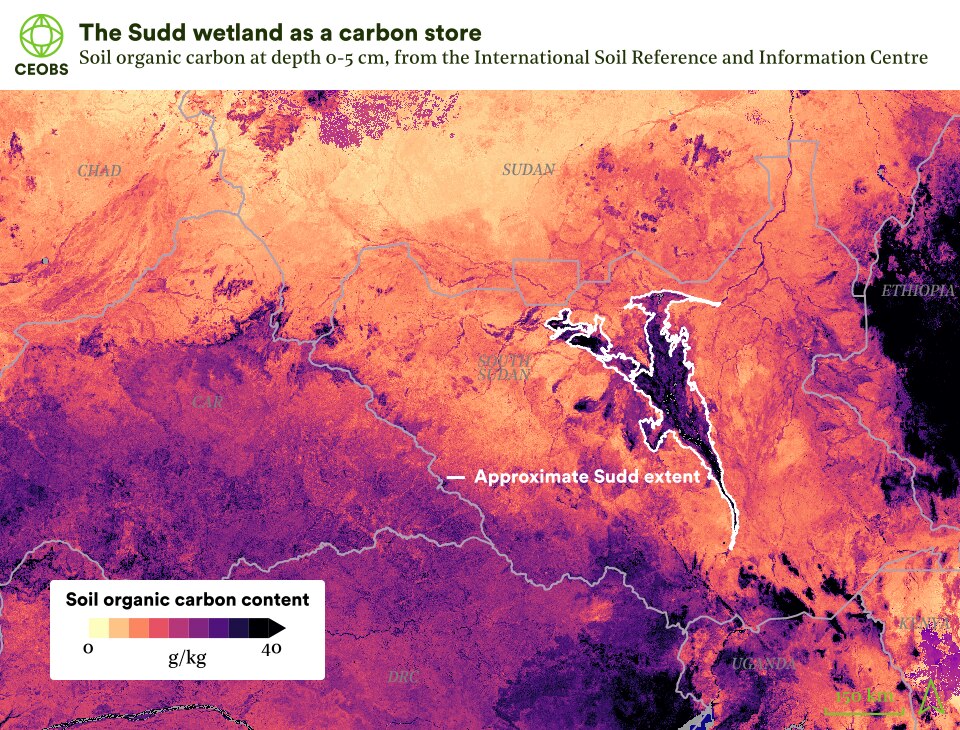

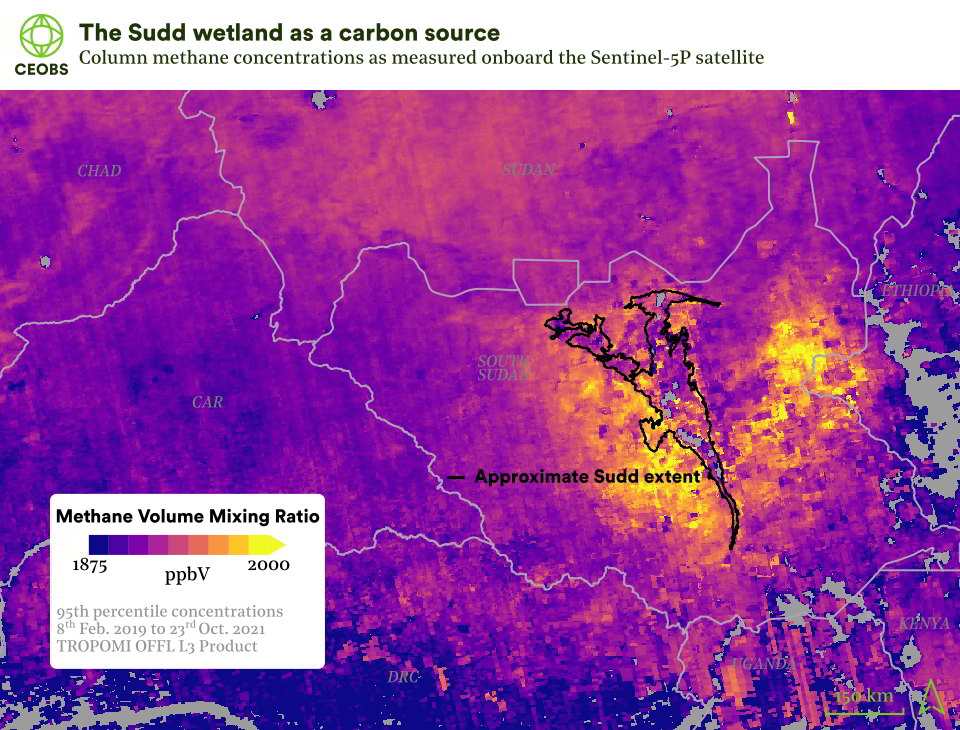

- One of the key arguments for the canal, and possibly to mitigate emissions from oil expansion, is to reduce the natural emissions of methane. However, the Sudd also stores carbon, and it is unclear if overall it is a carbon store or sink. Field research is crucial.

- If the wetlands are a carbon sink, and degraded areas can be restored, this opens up the Sudd’s potential as a huge carbon store – a global ecosystem service that should be compensated for in a manner similar to REDD, opening up a sustainable development pathway.

- One hope for the Sudd is the emergence of local civil society organisations. Although they face significant security and resource challenges, through their work the people of the Sudd are beginning to understand the threats they face. This is essential in holding the government to account.

Contents

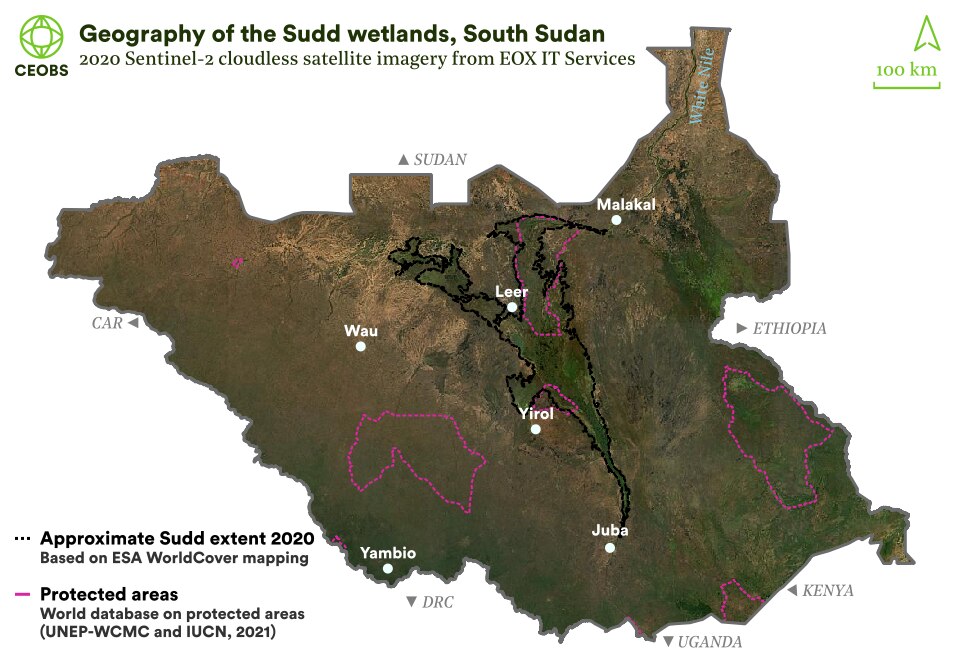

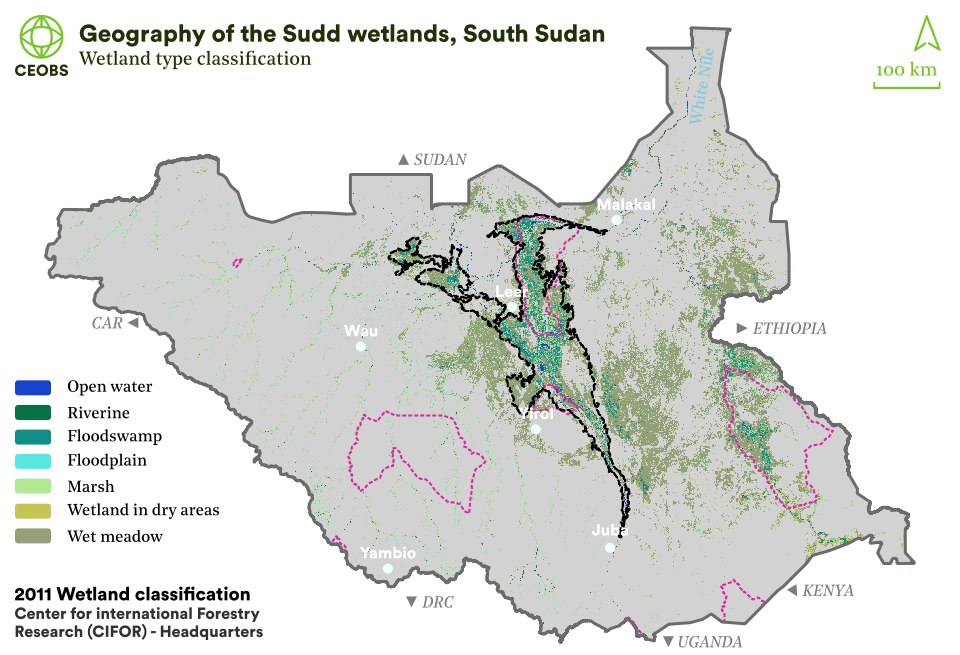

Figure 1. The Sudd’s geographic situation. Click left/right arrows to scroll through satellite imagery, land cover classification, and wetland type classification. More on the wetlands hydrology and future climate can be found in the accompanying article here.

1. Path of least resistance: Environmental destruction

1.1 Oil

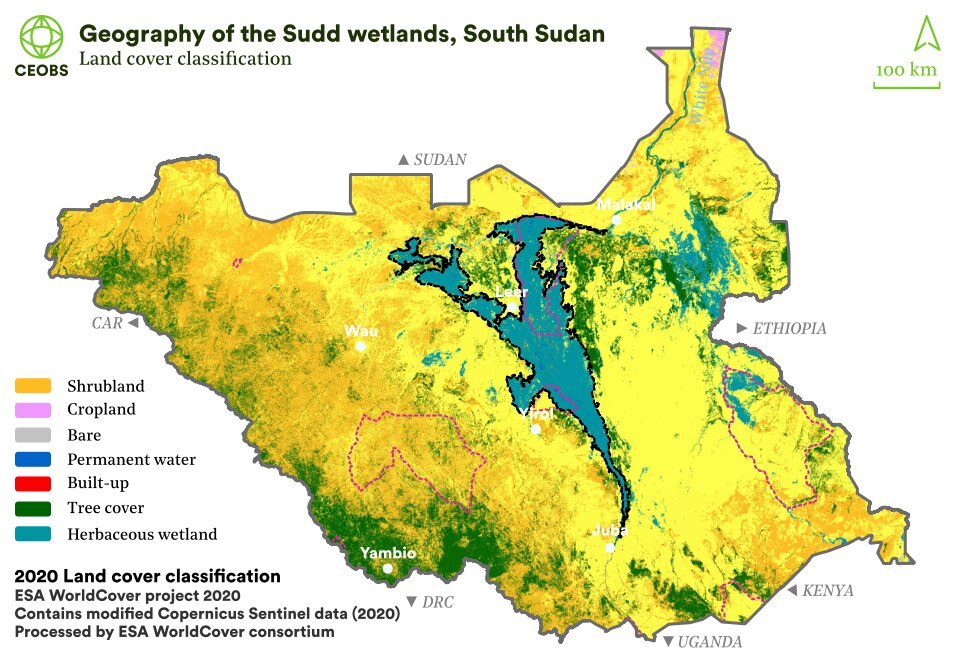

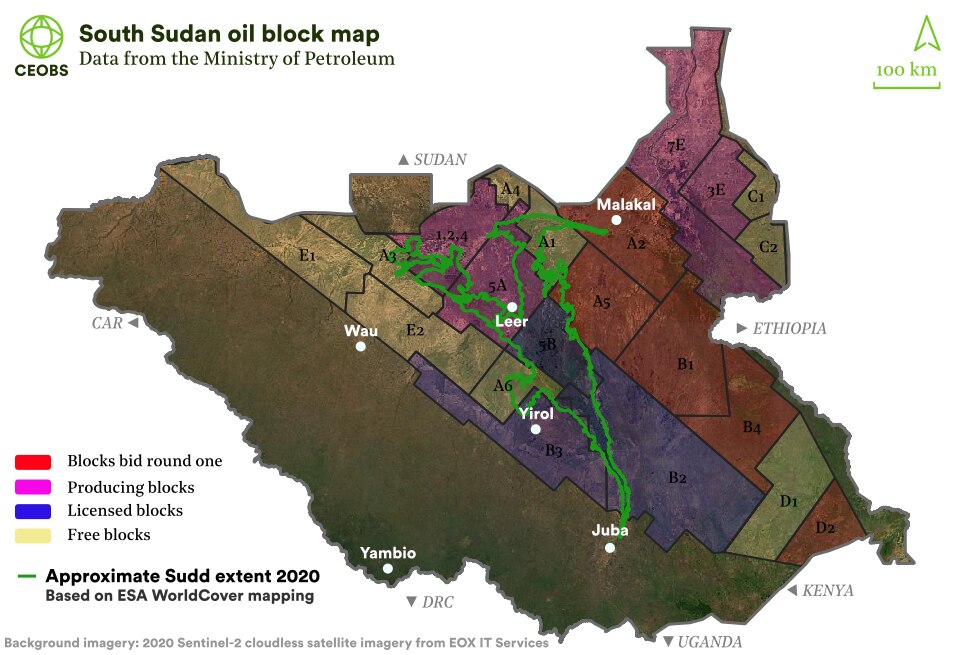

One of the clearest threats to the Sudd is from oil production and exploration. This is not a new threat, and has been going on for decades. The oil-producing block 5A straddles the Sudd and production in the southern portion restarted in June 2021 – it had been stopped for nearly eight years following the civil war. Likewise, the Benitui oil refinery came back online in August after sustaining conflict damage in 2014. Diplomatically, a thawing of relations with Sudan in September is now helping to ensure the continued flow of oil.

Figure 2. Map and status of oil blocks in South Sudan.

In the other oil blocks that have resumed production following the civil war, significant environmental pollution has been documented. A Bellingcat/PAX investigation found two pipeline spills and two large oil fires in blocks 1, 2, and 4, just north of the Sudd, and we have identified a continuation of such incidents.1

These events – and those that have undoubtedly gone unreported – add to the significant historical burden of oil pollution in the region. Pollution that has been the result of negligence, ill maintenance and mismanagement, and facilitated by the absence of environmental enforcement. Leaked internal reports from the government and oil industry acknowledge that they are aware of the scale and magnitude of the pollution and health impacts of the oil industry.

The most recent of these documented 650 waste pits contaminated with “extremely high” concentrations of heavy metals like lead and arsenic. Many of the pit’s liners had failed, allowing this pollution to leak into the wider environment. The Human Rights Council report found evidence that such negligence has severely impacted the health of the local population, documenting instances of preventable diseases and birth defects. The construction of roads for the oil industry has also affected local hydrology, with drainage into the Sudd blocked in some locations.

There remains a critical need for independent quantitative in-situ measurements to assess the full magnitude and scale of the damage to people and the environment. However, oil pollution is a very sensitive topic in South Sudan according to the Sudd Environment Agency (SEA), a civil society organisation formed in 2019 to advocate and help protect the environment in Unity and Upper Nile states. A spokesperson for the SEA told us:

“The government security apparatus are not allowing the civil society organisations or any individuals to have access to oil wastes dumping sites including taking of photos”.

Figure 3. Facebook post from the SEA showing oil contamination near Thar Jath in October 2021.

As was the case after production restarted elsewhere, recent reports from the SEA have revealed signs of new oil pollution in block 5A. Furthermore, the extreme flooding during October 2021 is likely to have a significant and long-lasting environmental and health toll. The situation on the ground is still unclear – the Thar Jath oil field in the Sudd is now inaccessible and most of the pipelines are reported to be underwater. This raises the possibility that produced oil waste pits have spilled over into the landscape.2 If contaminated water has spread directly over wetland, grazing land and into settlements and drinking water sources, this could represent an environmental catastrophe. This issue is not limited to the Sudd – in Paloch, north-east South Sudan, it has been reported that around 200 oil wells have been submerged. The waste management practices of the oil industry in South Sudan are seem incompatible with the climate of the country.

Figure 4. Existing and potential oil pipelines from South Sudan’s oil producing blocks.

Concerningly the scale of the threat could be set to increase. In June a new licensing round was launched to address predicted production declines, including for blocks A2 and A5 which also sit atop the Sudd. In November, a $1 billion oil investment by South Africa will begin – the deal signed in 2019 promised the building of a pipeline, refinery and the exploration and production of block B2 – within and upstream of the Sudd.

Furthermore, this summer has seen renewed political activity surrounding potential new pipelines through the wetland. For some time there have been suggestions of new pipelines to export oil from South Sudan. Before the October coup, which possibly led to suspension of oil production, there have been ongoing incidents – the most recent being in September, when protests from the Beja tribes in eastern Sudan forced the closure of the pipeline.

The long-held plans for new pipelines are perhaps now getting more serious. In June, South Sudan, Ethiopia and Kenya agreed to fast-track a $23 billion mega regional infrastructure development programme. This scheme is known as LAPSSET – the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport, and aims to develop a transport corridor from the in-construction Lamu port – itself the source of environmental controversy.

The deep-water port is being constructed by a Chinese company, and the LAPSSET corridor is seen as key for the Belt and Road Initiative. Here it is perhaps worth noting that the key oil producer in South Sudan is the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). Although no detailed pipeline plans have been provided, past media reports have placed the theoretical pipeline as travelling through or adjacent to the Sudd,3 as indicated in Figure 4.

The resumption of old production and old polluting practices, new exploration and licensing, and moves towards new pipelines could see oil dominate the Sudd landscape for decades to come. This could be catastrophic for the environment and the people, animals and plants that rely on it for their survival. Lessons ought to be learnt from elsewhere around the globe – the similarities between what has happened to the Iraqi Mesopotamian marshes and what could happen to the Sudd are striking.

1.2 Regional hydropolitics

Perhaps the most existential threat comes from the management of the White Nile and the surrounding regional hydropolitics. The South Sudanese government recently pledged to build a large dam on the White Nile, and signed a memorandum of understanding with Egypt to conduct engineering works to reduce the risk of flooding in the Sudd. On the face of it, this sounds sensible given the recent flooding – but works must be well designed to avoid compromising the Sudd’s ecosystem.

This work may also represent a precursor to a resumption of building the Jonglei Canal – a colonial-era project to divert the flow of the White Nile to bypass the Sudd, in order channel more water into downstream agricultural irrigation. There is renewed interest and political intent, especially following the fallout from the ongoing ‘Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam’, with one Egyptian researcher saying the help to South Sudan will aid “expediting the project to develop, expand and deepen the Jonglei Canal”.

Figure 5. Paths of the excavated and possible final section of the Jonglei canal.

The opportunity to reduce flooding, generate hydropower, facilitate agricultural expansion and reduce methane emissions (see below) may seem appealing to the South Sudanese government. Theoretically, it could be mutually beneficial if, in years of high rainfall, it could help avert the flooding seen recently, keep methane emissions low, and provide irrigation for cropland downstream, all whilst maintaining the function of the Sudd. How it could be mutually beneficial in years of low rainfall is less clear.

However, these ought only to be thought exercises for now. There is simply not enough known about the complex hydrology of the Sudd and its role in the wider Nile basin, in order to model the outcome of drainage. This is not a failure of the sophistication of models, but rather the lack of the on the ground observational data required to constrain the hydrological models. This was the finding of one of the most comprehensive attempts to model the Sudd hydrology, which was published this month in the Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies.

As in most conflict settings, the fighting has prevented the collection of key environmental data. Imperative now are in-situ measurements of the inflow and outflow, in addition to rainfall totals that can be used in cohort with high resolution satellite imagery to distinguish between areas that are hydrologically connected.

No robust feasibility studies on the Jonglei canal can be conducted until these data limitations are addressed. Then, modelling would need to be undertaken for different climate and upstream management scenarios in order to assess the impact, risks and feasibility of such a drainage canal. Are the recently announced government plans for studying the environmental impact of the canal going to take this complexity into account? Such large-scale hydro engineering projects are not trivial.

If undertaken without a sound evidence base, the canal could be catastrophic for people and the environment – impacting wildlife, vegetation, increasing flooding risks and possibly even influencing the regional climate. Such a move may also result in conflict both locally, as previously occurred in the 1970s and 80s, and regionally between other Nile states.

Further afield, flow into the Sudd may begin to be significantly affected by domestic and upstream damming practices. The most recent constructions are the Isimba and Karuma hydroelectric dams in Uganda – both have suffered delays but are now nearly complete and expected to come online in 2022 – whilst the much larger Ayago dam is further on the horizon.

1.3 Climate

The past three years have seen massive and unprecedented flooding in the Sudd, reflective of an increasing inter-annual rainfall variability and a changing climate. Climate projections indicate that temperatures – thus evaporation – will continue to rise, but there is less consensus on the changes to rainfall. More details on the climatic controls and changes are provided in our accompanying article.

South Sudan has developed plans to adapt to and mitigate climate change impacts through its first and second Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) to the UNFCCC. The first NDC specifically highlights the importance of the Sudd, arguing that it is:

‘…pivotal in regulating the weather patterns in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and the greater East Africa region. The Sudd acts as a barrier to the southward encroachment of the Sahara desert and its preservation and management is consequently expected to be South Sudan’s most significant contribution toward buffering against the impacts of climate change at the regional level.’

Intriguingly, and despite the fact the reports were submitted only seven months apart, the language and focus of the second NDC is different, with the role of the Sudd as key for regional climate modulation and mitigation no longer included.

Figure 6. The Sudd is both a carbon source and sink – the balance is not yet understood and this remains a major knowledge gap. Soil carbon data from ISRIC Africa SoilGrids. Atmospheric methane data from the TROPOMI instrument onboard the Sentinel-5P satellite (Copernicus Sentinel data 2021), calculated using version OFFL/L3_CH4 data in Google Earth Engine.

Instead, there has been a switch in focus to ‘Controlling emissions emanating from the wetlands’. This refers to recent research, where satellite data showed a globally significant methane hotspot over the Sudd. Recent wetter years saw higher emissions of this potent greenhouse gas. It has been hypothesised this is owing to the increased plant growth and soil microbial activity associated with the influx of water. However, this is contested, and the dominant control may in fact be temperature. We note that the role of an unattended and hibernating oil sector has not satisfactorily been addressed in these studies so far4 – but we know from other parts of the world that so-called ‘shut-in’ wells can be a major methane source.

The second NDC calls for ‘ground research on the release of methane emissions from the Sudd wetland and develop measures to sustainably manage and mitigate high emissions’ and this is important and necessary research. However, it is only half the picture. Tropical wetlands are also significant stores of carbon through sequestration of carbon dioxide. The rewetting of drained tropical wetlands is now understood as a key and potent mitigation measure, particularly in the Nile basin. However, this carbon balance between methane release and carbon dioxide sequestration is unmeasured in the Sudd. This suggested research is omitted from the second NDC, but it is imperative that we know whether the Sudd is, on balance, a carbon source of sink, and how this has and is projected to vary over time. This information can then be included in cohort with the hydrological modelling to understand the behaviour of the wetland as a system.

Why the change in message between the first and second NDC? Why the focus on methane emissions and not carbon dioxide sequestration? A cynical hypothesis might be that a reduction in methane emissions, for example through construction of the Jonglei canal, would help balance new emissions from oil production, reduce flooding damage, increase agricultural production, and bring significant geo-political benefits by providing more water downstream.

2. Path of most reward – preserving the Sudd

2.1 Ecosystem services in a changing climate

A recent report by the secretariat of the Nile Basin Initiative, an intergovernmental partnership of 10 Nile Basin countries, estimated the total economic value of the ecosystem services of the Sudd. To calculate this, they took an approach based on the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity, which attempts to place a financial value on ecosystem services – using the traditional economic market valuation measures is inappropriate.

The total economic valuation was estimated at $3.3 billion – primarily owing to the climatic regulation, flood control and biodiversity services, but also through provisioning services including livestock grazing and watering, fishing, and papyrus crafts. Such estimates do require some scepticism – for example, the role of the Sudd as a regional rainfall modulator remains unclear, and more data collection and modelling is required to be able to more accurately value this.

Despite the huge economic value of the Sudd, these are not directly transmitted to the wallets of those living there, and so there remains a need to develop provisioning services in a sustainable way. Proposed solutions like agricultural intensification are likely incompatible with wetland preservation. However, there is currently little research into environmentally and economically sustainable alternatives. Given the biological diversity and unique landscape, tourism is often put forward as a potential solution and it is even estimated that a well-managed high-quality, low volume industry could generate $600 million per year. However, whilst insecurity reigns, it is difficult to see how the tourism industry could begin to grow.

One promising opportunity may be through wetland restoration. This would create new and, if undertaken considerately, enhanced ecosystem services, in addition to jobs and potential carbon sequestration. In the words of Jane Madgwick, CEO of Wetlands International:

“The science on the importance of wetlands is in. And the technical know-how of restoration is well demonstrated. Affordable and scalable nature-based solutions are ready to be deployed, with local communities and Indigenous people at the heart of the action.”

Figure 7. The Nile River at Bor Town in Jonglei, South Sudan. Credit Joesph King, Flickr.

In its second NDC, South Sudan lists wetland reclamation as one of its intended mitigation strategies, but no work has been undertaken so far. So what is the hold up? The first problem is that the scale of restoration is unmapped and so it is not possible to assess the scale of the benefits – this is urgent research work that could be undertaken.

Assuming the scale is sufficiently large, then the next issue is finance. Wetland reclamation is hard to fund because the benefits are often diffuse and not tangible – compared to reforestation for example. However, the amount needed by South Sudan for all ‘Biodiversity, ecosystem and wetland management mitigation’ is just $15 million, and includes other much needed strategies and research. This is small change in the scheme of the $100 billion climate finance promised for developing countries, and the type of nature-based solution that is being championed at COP26 by the UK government.

An alternative funding source may be Payment for Ecosystem Services, an approach where downstream beneficiaries pay for the services, although this has been difficult for wetland restoration thus far, and likely complex given the hydropolitics of the Nile basin. There is no wetland equivalent to the UN Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) programme, which pays for results-based emissions reductions.

2.2 Pay to keep oil in the ground

The recent report by Crisis Group into how South Sudan’s corrupt oil wealth has not improved the lives of its people, and has instead fed conflict, had a novel suggestion for donors – payments to leave the oil in the ground.

At first this seems a far-fetched version of payment for ecosystem services. However, it does make sense, could be beneficial for all, and is an increasingly compelling case. First of all, oil revenues are relatively small, yet intrinsically linked with conflict. Decentralised payments to keep oil in the ground could be the key to peace – and the sustainable development that could follow. Further, the environmental and health gains would be hugely significant, especially compared to the counterfactual of increased production, and thus pollution. More broadly, the gains for the global climate could be important, especially if combined with wetland restoration.

Such a move would take bravery on the part of international donors, but they are already embedded in the country and it is exactly the type of innovative move that is required to address the local governance challenges and global climate and biodiversity crises. Such an initiative could act as a pilot for other low-income and conflict-affected countries that struggle to decarbonise and regulate environmentally harmful extractive industries.

2.3 Role of civil society

One hope for the Sudd is the emergence of local civil society organisations. In particular the Sudd Environment Agency (SEA) is at the forefront of advocacy. The organisation was formed in 2019 and to advocate for the protection and preservation of the environment with a particular focus on oil pollution. They undertake field assessments and workshops to help educate and raise the awareness of local communities and the authorities.

The SEA has recently spearheaded a new consortium with the aim of strengthening advocacy. The Environment and Climate Change Network brings together four civil society organisations – Yo’ Care, People Initiative Development Organization, Africa Centre for Research and Development, and the SEA. The Sudd Institute, an independent research organisation with the aim of improving decision making in South Sudan, has also produced reports on the impacts of oil pollution.

Internationally, civil society efforts to advocate for the Sudd have been led by the German NGOs Sign of Hope (Hoffnungszeichen) and For South Sudan. Their submissions and advocacy work have been key to the recent Human Rights Council report.

Together, the work of civil society has exposed the practices of the oil industry and been able to transmit this to communities. This has even led to protests, such as last September in Upper Nile State, where hundreds of young people carried placards, barricaded roads and demanded the suspension of oil operations.

However, civil society in South Sudan faces many barriers, and the SEA outlined their main challenges to us. They say that the major factor exacerbating the spread of oil poisoning on the environment is the unsafe and dangerous working environment in South Sudan, where the government does not cooperate and instead cracks down on journalists and activists. This extends to the oil fields, where field assessments, even to take photographs, are impossible and very dangerous. South Sudan was deemed the most dangerous country in the world for aid workers in 2020, and difficult for foreign journalists. Unfortunately, the SEA concedes that advocacy is currently achieving little due to “government acquiescence” to the oil industry.

One of the most pressing tasks for civil society is to ensure ‘the immediate’ environmental audit of oil blocks ordered by the government in June 2021, is undertaken at all, and is undertaken properly. This announcement was met with a backlash from the oil operators, and the audit has not yet started. There is little trust from the public and civil society that it ever will.

The other challenges facing the SEA are limited equipment and resources, and no assessment tools to conduct field measurements, no website for advocacy and education, and being able to bridge the knowledge gap to communicate environmental hazards to local communities. We call on fellow organisations and donors to provide more help, support and solidarity towards the local civil society organisations that are helping to protect the Sudd. Support could be through partnerships, involvement in global networking events, training, co-design of assessment tools, and financial support – especially to pursue legal action.

3 Concluding thoughts

Which path the Sudd takes is now dependent on decisions by the South Sudanese government in the near-term, and the role of the international community in shaping these. Down one path – the path of least resistance – lies further oil exploration, drainage for hydropolitical gain and a continuation of the status-quo and conflict that has been so damaging for the Sudd and to South Sudan. Down the harder but more rewarding path is preservation, keeping oil in the ground to help peace, addressing other threats,5 and fully capitalising on and supporting the ecosystem services the wetland can provide in a changing climate.

Down either path lies uncertainty – there is simply a huge knowledge gap when it comes to the Sudd, and it is critical there are now further observations and research into its hydrology, its role as a carbon source or sink, its role in flood prevention, its capacity to modulate the regional climate, and into the damage from oil production. So we also call on academics, civil society, donors and the South Sudanese government to realise this urgent research.

Eoghan Darbyshire is CEOBS’ Researcher. Our thanks to the Sudd Environment Agency and Courtney Di Vittorio from Wake Forest University for providing insights and assistance.

- There seems to be dumping of produced oil in May 2021 at 9.495°N, 29.90843°E and in July 2021 at 9.645°N, 30.039°E, and a nearly 5km2 expansion of large produced water ponds at 9.79°N, 29.63°E during 2021.

- It is difficult to determine waste-pit leakage remotely without ground verification – which, as we explore in this article has difficulties for local civil society. It is for this reason we made the decision to remove a figure showing potential spillage from a waste pit that appeared in an earlier version of this report.

- For example, Stratfor in 2012 and 2013, the Economist in 2013, and open briefing in 2013.

- Although the measured signal shows a strong seasonality, indicative of biogenic emissions, it is not clear if this is superimposed on an increasing year-round baseline from oil infrastructure.

- Such as: plans to make the White Nile from Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean navigable, for which there are many environmental concerns but again a big knowledge gap; poaching of the remaining wildlife that has already suffered from arms proliferation; vegetation clearance and logging, particularly though fire.