The screening of existing and new military-use substances for environmental and health risks is being viewed as increasingly important.

Many substances that are currently used for either civilian or military purposes have been proven to have adverse environmental impacts, or present unacceptable risks to human health. As a result the screening of substances prior to their production and use is now recognised as an important means of protecting environmental and public health.

Examples of chemicals screening

To screen a substance means to subject it to study in a way that measures its potential environmental and health impacts, based on knowledge of chemical structure in the first instance, followed by computational modelling, laboratory and environmental testing.

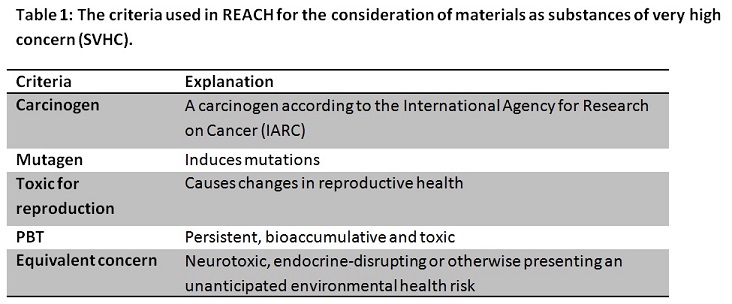

The EU regulations for Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) adopted in 2007 are now considered a benchmark for the screening of chemical substances that are in commercial use. REACH requires industry “to ensure that the substances they manufacture, place on the market or use do not adversely affect human health and the environment”. As a part of REACH, the manufacturers and users are required to screen chemicals for their safety and, if deemed necessary, substitute them for safer substances. Within the REACH system, substances are assessed based on multiple criteria, mainly in relation to human health but also for environmental impacts. If one or more of the criteria in table 1 are met by a substance then it may be proposed as a substance of very high concern (SVHC).

Other factors also come into play for substances to become a SVHC, most importantly being very persistent, bioaccumulative or toxic, widely dispersed during use and produced in large quantities. An example of a SVHC is dinitrotoluene (DNT), which is a minor constituent of explosive compositions but has also been known as an impurity in TNT. DNT is a SVHC because of its carcinogenicity. The REACH assessment of DNT considers that its major health and environmental risks are related to manufacturing with no risks to consumers in the traditional sense. The assumption that there are no ‘consumers’ of DNT is a reasonable one in the context of the EU; however it remains to be known what the exposure risk is when DNT contaminated TNT is used in urban conflict zones.

As a progressive approach to chemicals safety assessment, REACH has had knock–on effects beyond the EU and consumer goods. Several programmes within the US DoD, such as the Chemical and Material Risk Management Directorate (CMRMD), are working on compliance with REACH. REACH compliance has been identified as posing a threat to the ability of the military to use certain substances. So the necessity of complying with REACH meant that certain aspects of the military supply chain could be threatened and that it could be difficult to identify replacement substances with the same level of performance as the originals, nonetheless this can be done. Examples of substances subject to the scrutiny of CMRMD because of pressure from civilian environmental legislation include RDX, hexavalent chromium, perchlorate and lead.

As has been noted previously, and beyond protecting military capabilities and supply chains from REACH, the motivation for the replacement of certain substances has been to protect troops from toxic exposures and to allow the continued functioning of military facilities, testing and training ranges in the face of domestic environmental regulations. The issue of civilian protection in relation to military materials has typically been absent from these considerations, which is a regrettable oversight.

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) Screening process

Advances in the understanding of natural and manufactured xenobiotic1 chemicals and their toxicological and environmental effects, has led to pressure for environmental legislation to protect from these substances.

Compliance with environmental and health protection legislation therefore requires a pre-emptive approach to chemical safety. The ASTM Guide for “Assessing the Environmental and Human Health Impacts of New Energetic Compounds”2 is a prime example of such an approach.3 The guide has a stepped approach for the assessment of substances replacing older problematic ones. Beyond energetic compounds, many commonly used military materials are in need of replacement because of adverse health and environmental effects. For example, the obscurant hexachloroethane (HCE) is currently being considered for replacement because of its effects on the respiratory system; part of the testing process was guided by ASTM E2552-08.

When using ASTM E2552-08, the first stage is usually the development of “conceptual replacement substances” through computer modelling. These substances can be ranked based on their physical, chemical and toxicological properties.4 Those that exhibit favourable properties in comparison to the original substance, and fulfil the same function, are passed to the next stage of development and subsequent testing. These likely candidates are synthesised in small quantities to allow the determination of their properties. Substances that pass this stage proceed to be made in larger quantities for more detailed in vitro and in vivo toxicological testing and environmental testing, in addition to the testing of their performance.

When using ASTM E2552-08, the first stage is usually the development of “conceptual replacement substances” through computer modelling. These substances can be ranked based on their physical, chemical and toxicological properties.4 Those that exhibit favourable properties in comparison to the original substance, and fulfil the same function, are passed to the next stage of development and subsequent testing. These likely candidates are synthesised in small quantities to allow the determination of their properties. Substances that pass this stage proceed to be made in larger quantities for more detailed in vitro and in vivo toxicological testing and environmental testing, in addition to the testing of their performance.

In theory such an approach should allow the identification of those substances with the fewest environmental and health impacts. It is to be expected that other factors such as cost and the suitability of substances for the purposes required by the military will also influence decisions. Increased non-military involvement in the consideration of replacement substances seems a means of ensuring lack of bias caused by a focus on operational purposes.

Commentary and conclusions

Guidelines and approaches for the pre-emptive screening of chemical substances are potentially useful exercises in due diligence, for both health and environmental protection.

Currently, the review process for the introduction of new weapons under international humanitarian law (IHL) is not specific enough to control the nature of munitions constituents from a chemicals safety perspective. The incorporation of procedures such as ASTM E2552-8 into processes like the Article 36 reviews would be a welcome means of improving both civilian and troop protection. However, these guidelines are only as good as the extent to which they are applied for the replacement of old and problematic substances. From available information online it appears that US military developers have adopted such standards to varying degrees.

There is a growing awareness and interest in the screening of toxic military materials, however the extent to which various militaries apply procedures such as ASTM E2552-8 is not known, as is the uniformity of individual approaches. As an example of this interest, several NATO member states are working on a standardisation agreement (STANAG) for screening the toxicity of military smokes and obscurants, however it is in the early stages of development. The extent to which other militaries outside NATO are committed to screening for the toxicological and environmental impacts of munitions is also unknown.

As noted previously, most of the military motivation for seeking less toxic substances is for troop protection and range sustainability. While there is no explicit focus on civilian protection, it has been argued that munitions and materials that are less harmful to troops and military facilities from a health and environmental perspective will also be less harmful to civilians in conflict zones. The assumption that troop and range safety is equivalent to civilian and urban safety is not wholly incorrect; however it does not take all relevant factors into account. For example, the larger number of people exposed to munition and other military remnants; the differences in types of emissions at the firing point versus the target point; the fact that civilian populations during conflict are under psychological and physical stress; that there are certain sections of the population that will be particularly vulnerable, even to low concentrations of toxicants; the different health impacts of chronic versus acute exposure and to the impact of mixed exposures to a range of toxics.

The balancing of issues of military utility and environmental health considerations is a long running debate. Nonetheless, the matter of military utility has proven to be an important barrier to the discontinuation of munitions and practices with toxic and environmental risks. As mentioned, there have been recent encouraging steps towards the development of munitions and military practices that are less harmful to environmental health. Nonetheless, previous experiences with environmentally damaging munitions emphasises the need for engagement from actors outside the military in the replacement of old munitions. Examples of note are the ongoing impasse regarding a ban or moratorium on depleted uranium weapons and the prioritisation of military objectives in the past use of Agent Orange herbicides, to the detriment of the health of both Vietnamese civilians and US veterans.

Without increased external pressure, militaries may be all too ready to delay or avoid the replacement of other substances that are deemed valuable from a military standpoint (e.g. RDX, TNT, hydrazine). Pressure from civil society and other external stakeholders could provide the requisite counterbalance to ensure that war does not cause undue additional suffering through the generation of pollutants.

Finally, while the replacement of current harmful military substances is an important and welcome advance, it is only part of the wider situation regarding existing contamination from military activities. There are enormous worldwide stocks of old military materiel that continue to pose a risk to environmental health and that will remain a problem for decades to come. Therefore, beyond the replacement of problematic substances, it is necessary that environmental issues regarding the use of current munitions, their storage and disposal, be better scrutinised as a matter of environmental protection over military imperative.

Mohamed Ghalaieny is a researcher for the Toxic Remnants of War Project

- Foreign chemical substances that are not produced within a living organism, or expected to be within it.

- Energetic compounds or energetic materials are substances that contain a high amount of stored energy that can be easily released, such as explosives, propellants and fuels.

- ASTM E2552-08

- Physical and chemical properties can be calculated using computer models known as quantitative structure activity relationships (QSAR) and toxicological properties are found using quantitative structure property relationships (QSPR).