While most mine action operators agree that environmental protection is important, it’s not clear whether the right policies are in place and being properly implemented.

In early March 2020 we invited representatives from the Humanitarian Mine Action sector and Unexploded Ordnance (UXO) contractors to take part in a consultation on environmental practices in mine action, with the aim of understanding current perceptions and practices. This blog reports on the results of the consultation.

How important is environmental management to the sector?

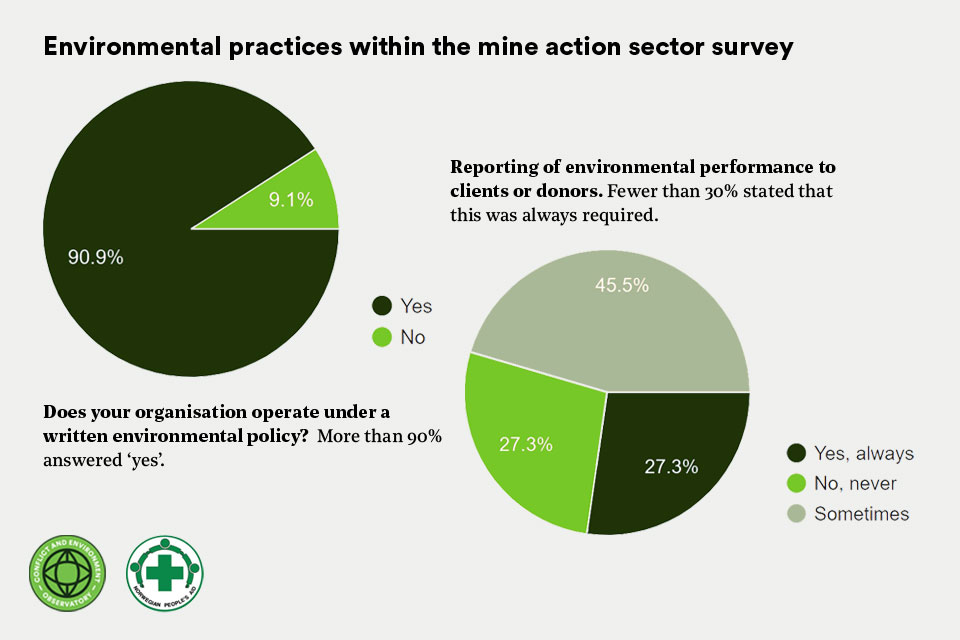

In total, 11 operators responded to the consultation. Encouragingly, more than 50% of them ranked the management of environmental issues in relation to mine action as ‘extremely important’ and none reviewed these as ‘not important’. Just over 90% have a written environmental policy, with the majority reporting that their policy and procedures were considered fully adequate. Only around 25% noted that their policy required improvement.

Environmental management frameworks however were not typically certified or independently reviewed, and the majority (64%) have no Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) to measure the effectiveness of environmental measures in place. To work well, a management system must have commitment from all levels, with continuity and monitoring in place to measure performance and direct on-going improvement. Without resourcing to support this, there is a risk that frameworks already in place will fall short of optimising the environmental benefits that could be achieved. Reporting of environmental performance to clients or donors is also not common practice, with fewer than 30% stating this as a mandatory requirement.

What are the key environmental issues in mine action?

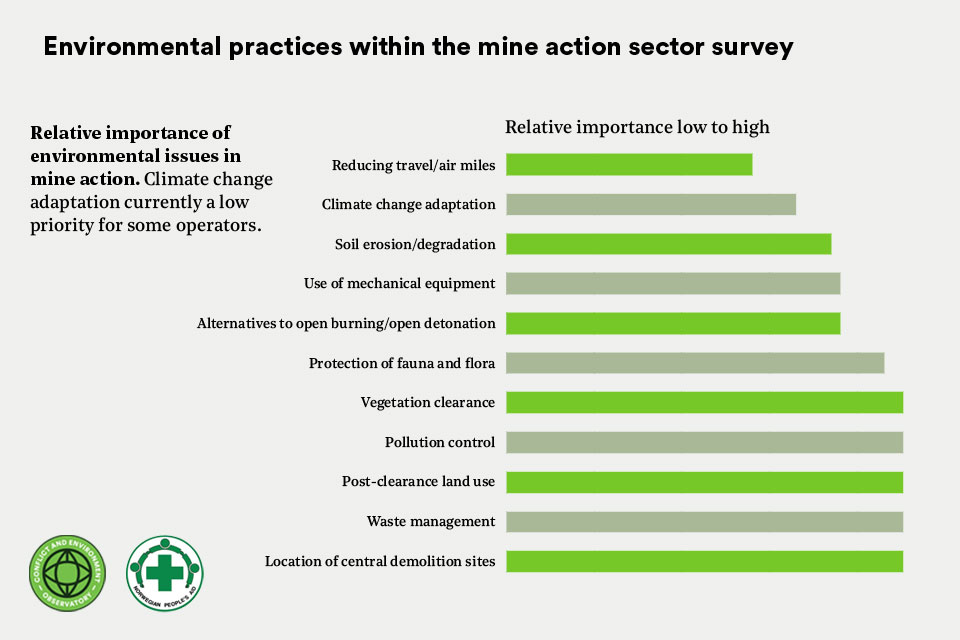

We asked respondents to rank the importance of environmental issues for mine clearance and disarmament. Waste management and the location of central demolition sites (CDS) scored the highest, followed by post clearance land use and the control of pollution.

Climate change adaptation planning and reductions in travel/air miles received the lowest relative scores. The low score for adaptation planning perhaps highlights a need for more awareness raising, especially given the potential for climate change to impact mine action due to flooding, drought or other extreme weather, by disrupting clearance programmes and planning.

So, why are environmental issues not always being effectively managed across the sector? The reasons suggested by respondents include a low prioritisation of the environment, time constraints, the perception of high-costs to implement measures, a lack of training, and low understanding of the potential significance of environmental risks and consequences. A lack of consistent policies and appropriate technologies adapted to humanitarian mine action operations were also reported, compounded by poor infrastructure and the absence of environmental governance within the regions in which the sector typically operates.

In countries where there is already a struggle to meet even basic needs of the population, management of the environment will often be regarded as a lower priority. It is evident from the responses that, whilst there is willingness to address environmental concerns, safety and security issues understandably take precedence, with the key priority being to remove the immediate risk of severe injury or threat to life.

How can environmental performance be improved?

It seems clear that although improvements in environmental management have been made in recent years, and in some cases effectively managed, further improvements can be made. This includes making a commitment to provide adequate resources, to educate and train staff, to improve waste management, to increase the use of renewable resources, and to share good practice and develop more detailed international and national best practice guidance on how to achieve this.

Although seeking alternatives to open burning and open detonation (OBOD) techniques for the disposal of unexploded ordnance did not receive the highest score in the ranking of key environmental issues (see above), it is acknowledged as an important area to be addressed. The potential long-term effects of soil and water contamination due to OBOD activities within the context of the humanitarian sector needs to be better understood, with research into viable alternatives and mitigation practices.

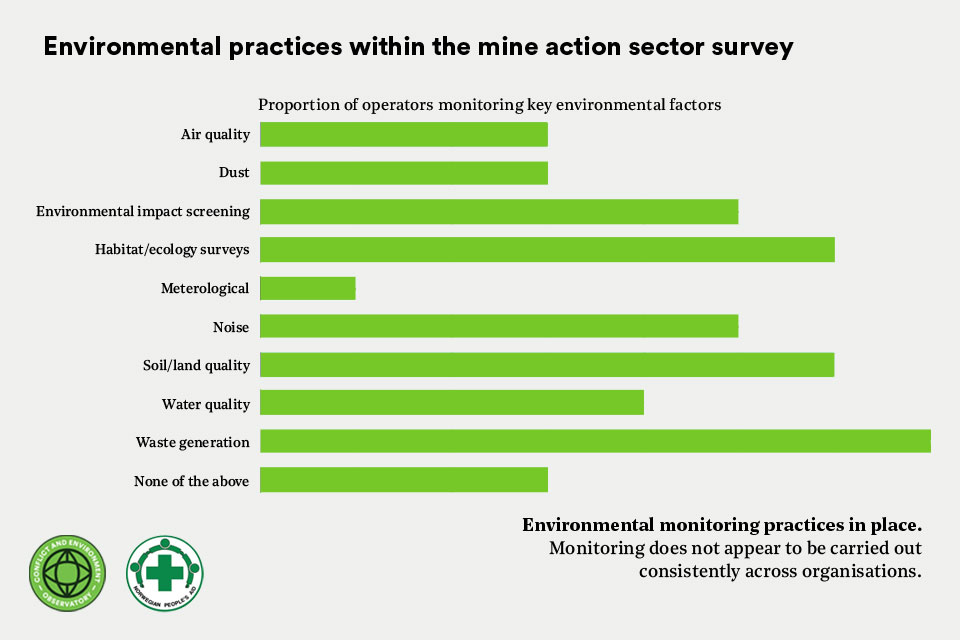

Several respondents reported a range of environmental monitoring practices in place to assess potential impacts such as dust, air quality, waste, water, soil quality, noise and habitat/ecology surveys, as well as the use of environmental impact screening and assessment techniques. Around 25% of respondents did not carry out any of the environmental monitoring listed. Without monitoring or measuring environmental performance, it will remain difficult to manage or assess any improvements.

Key actions for regulatory authorities or governing bodies suggested by respondents included developing their own environmental management policies, and a requirement for mine action organisations to demonstrate that they operate under an effective environmental management system, with accredited Standard Operating Practices. Regulatory authorities would also need to implement monitoring and enforcement of the best practice standards. In regions where effective regulatory authorities or governing bodies are absent, self-monitoring and compliance by mine action organisations is required.

Whilst some donors do require environmental impact assessments (EIA) to be carried out or evidence given to show that commitments are in place to minimise the potential for environmental harm, this is not mandatory. The sector would benefit from streamlined EIA guidance, for example through the International Mine Action Standards (IMAS).

Next steps?

The consultation proved useful in providing insights into current practices and suggestions for improvements across the sector. Whilst some did think that the main environmental issues were already being effectively managed, others recognised the need for improvements, including the need for more detailed guidance covering EIA, control of pollution, selection and location of disposal sites and measures to protect flora and fauna.

Our thanks to all who replied, in spite of the COVID-19 crisis. We shall look to take these points forward as part of discussions with the newly formed Working Group on Environmental Issues and Mine Action (EIMA) which had its inaugural virtual meeting on 21st April 2020, with further meetings planned quarterly. If you are interested in joining, please contact Kendra Dupuy at KenDup785 at npaid.org.

Linsey Cottrell is CEOBS’ Environmental Policy Officer, Kendra Dupuy is a Senior Environmental Adviser at Norwegian People’s Aid. Our joint project is funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.