Another UN debate has revealed significant differences in national positions over key principles of environmental protection in conflict settings.

Last week, quite a lot of governments said quite a lot of things about 2015’s report from the International Law Commission on legal protection for the environment during armed conflicts. This blog takes a look at what was said, who said it, why it matters and what it tells us about the hopes for more effective protection for the environment from the impact of armed conflict.

UN General Assembly debate

Shortly after the UN’s Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict, the UN General Assembly’s Sixth Committee (legal matters) debated the second of three reports by the International Law Commission (ILC) on protecting the environment in relation to armed conflicts. Regular readers will have seen our previous summary of the preparatory debate and the debate on the first report, which took place in 2013 and 2014 respectively.

Under Special Rapporteur Dr Marie Jacobsson, the ILC has been seeking to clarify the current status of legal protection for the environment before, during and after armed conflicts. The process was initiated by a 2009 recommendation from UNEP that such an initiative was long overdue, particularly as the development of International Environmental Law (IEL) had far outpaced that of International Humanitarian Law (IHL). Furthermore, there is a growing appreciation that Human Rights Law (HRL) may also confer certain obligations relating to environmental protection.

Identifying who’s progressive – and who isn’t

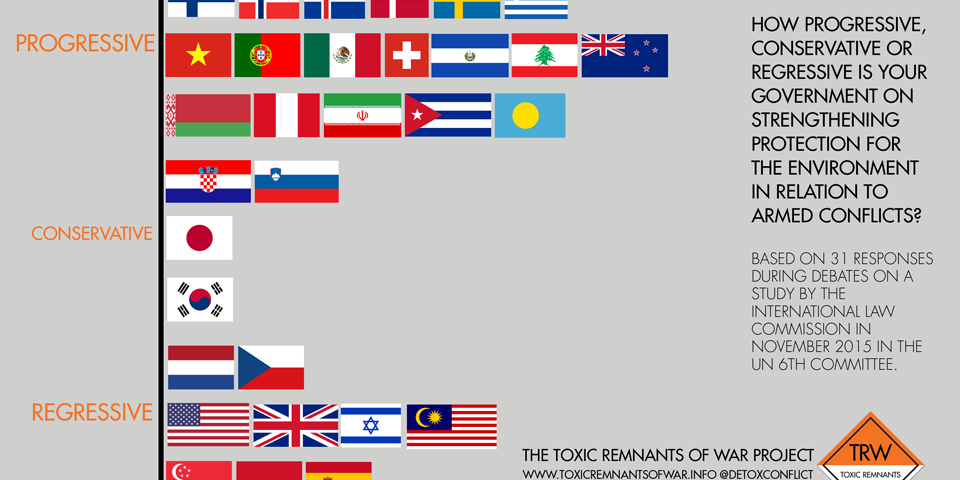

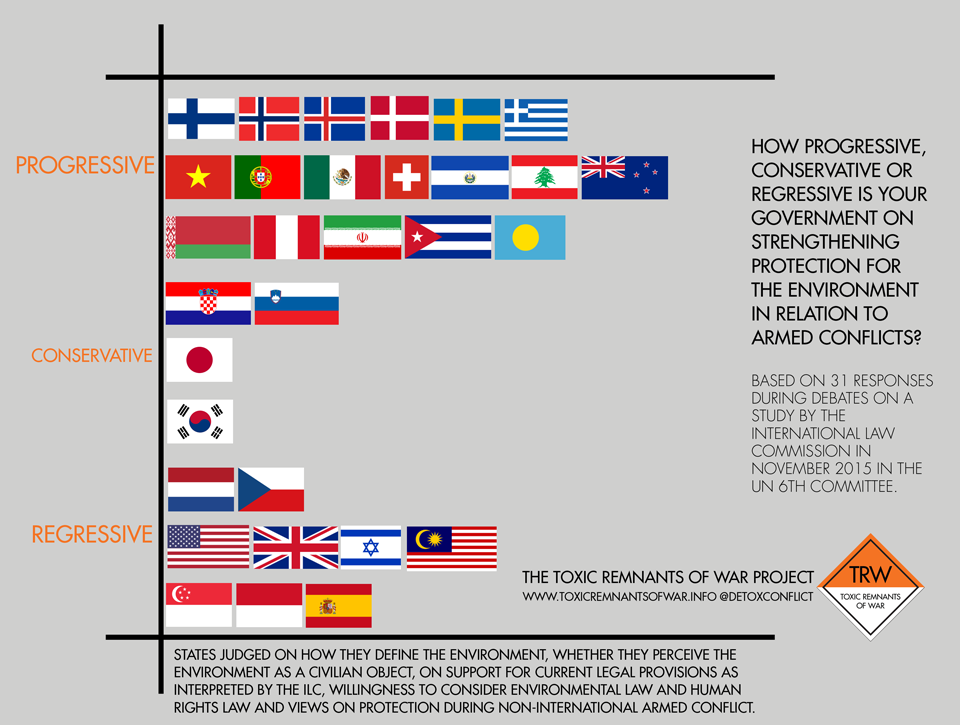

During the two previous debates, and beyond the procedural matters relating to the study’s scope, the issue of the applicability of norms and principles from IEL and HRL had become a defining factor separating out those who are progressive on the topic, from those who are ambivalent or conservative – or even regressive (see this graphic for details). Evidently the topic is of growing interest to states as almost as many spoke during this session (31) than had spoken during the two previous debates combined (32). In total, 43 governments have now expressed their views across the three debates.

Last week, statements were made by Norway on behalf of the Nordic group, Singapore, Greece, Cuba, Belarus, the UK, the Netherlands, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Lebanon, Austria, Portugal, Croatia, El Salvador, Iran, Poland, Palau, Japan, Vietnam, Malaysia, the US, Israel, South Korea, Switzerland, New Zealand, Mexico and Spain. In previous debates, the absence of states affected by serious wartime environmental damage had been troubling and in this regard the views of El Salvador, Lebanon and Vietnam were particularly welcome, as were the contributions of Palau and Iran.

Lebanon discussed the health, economic and environmental impact of the 2006 Jiyeh power plant bombing and subsequent oil spill, while Vietnam drew attention to the humanitarian and environmental legacy of explosive and toxic remnants of war and argued in favour of environmental impact assessments for weapons. Palau discussed the environmental impact of abandoned WWII ordnance on health, food security and sustainable development. Interventions like these help to contextualise what at times is a relatively abstract debate and more affected states should be encouraged to engage with the process.

This year, and due to the ILC’s second report focusing primarily on the law applicable during armed conflict, there was language to discuss and law to debate. The debate focused on a series of draft principles synthesised from treaty-based and customary IHL, many of which would seem fairly non-contentious to the casual observer but were nevertheless seized on by the less progressive states and given a thorough working over.

The treatment of the draft principles, the approach taken by certain states to how we define the environment and on the applicability or otherwise of IEL and HRL, revealed a growing polarisation between progressive and regressive states. Two other contentious topics related to the definition of the environment as a civilian object, and to whether and how the study should address environmental protection in relation to non-international armed conflicts (NIACs). A few states, such as Spain and Poland even questioned the merits of the enterprise as a whole.

Defining the environment

How the law defines the environment matters, particularly when the purpose of that definition is to identify what it is that should be protected. Attempts to define it for the purposes of IEL frameworks have been underway for many years and the starting point chosen by the Special Rapporteur in her first report used a variation on the definition developed by the ILC for a previous study on allocating losses from transboundary environmental damage. The proposed definition in the first report was: “”Environment” includes natural resources, both abiotic and biotic, such as air, water, soil, fauna and flora and the interaction between the same factors, and the characteristics of the landscape.”

However, AP1 of the Geneva Conventions uses the term “natural environment”, which the ICRC commentary to Article 35 defines as the: “…system of inextricable interrelations between living organisms and their inanimate environment”. Thus it is differentiated from effects on the “human environment”, which are understood as: “…external conditions and influences which affect the life, development and the survival of the civilian population and living organisms”.

The ILC’s draft principles, which were the main focus of the debate last week, saw the term presented as the “[natural] environment”, reflecting the debate within the ILC and among states over the draft definition. States that made a point of supporting the “natural environment” term included the US, Japan, ROK and the UK. Lebanon suggested that one should be chosen but had no preference, Vietnam supported “the environment” and Israel appeared to as well, though not explicitly. Austria called for the term to be better defined, Croatia supported the ILC’s starting point for the definition and New Zealand felt the ILC definition was fine for now. Malaysia completely rejected the idea that a definition from IEL could be transposed to a conflict setting while the Netherlands disappeared into an existential tangle over which parts of the environment the term was referring to.

We believe that as it’s increasingly clear that wartime damage to the environment carries with it consequences for the civilian population, this should be reflected in the definition. In this respect it was notable that a number of more regressive states went to the effort of advocating for the use of the “natural environment”. Excluding human factors from the definition not only helps isolate the protection of civilians from the protection of the environment, but it also makes little sense from a scientific perspective. Not only are there few ecosystems untouched by human influence but it also rejects the vital function that healthy ecosystems play for human health and livelihoods.

The environment as a civilian object

Following on from the debate over definitions, the issue of whether the environment is a civilian object was also spotlighted during national statements. In her second report, the Special Rapporteur had proposed that:

“It is possible to conclude that the natural environment is civilian in nature and therefore not in itself a military objective. As with other civilian objects, it may be subject to attack if it is turned into a military objective.”

This was interpreted mainly from AP1 and the Rome Statute, both of which have helped define the environment as a civilian object.

The question of whether the environment should enjoy similar levels of protection under IHL as that afforded to civilian objects was underscored by an emerging line on balance from Iranand Poland, who identified what they saw as tension in the debate between balancing the “legitimate rights of states” while protecting the environment. Israel argued that current legal protection for the environment under IHL is already equivalent to its protection for civilians, and that the ILC should go no further – which may be a question of perception, rather than reality. Japan cautioned against breaking the balance between military necessity and humanitarian protection, arguing that the development of new norms could result in “a higher risk of incompliance” with IHL. The UK entirely rejected the suggestion that the natural environment was a civilian object for the purposes of IHL.

The idea was also rejected by Croatia, was branded as “problematic” by the Netherlandsand in need of clarification by Slovenia, who argued for “caution” in transposing civilian protection norms to the environment. But others were more nuanced. Belarus, in what was broadly a very progressive statement, accepted that the environment was “generally civilian in nature”, while El Salvador also had objections but these mainly related to the different temporal characteristics of environmental damage as compared to civilian harm.

As with the question of definitions, we feel that enshrining the linkages between civilian protection and environmental protection is crucial, even more so when the current debate appears to be running the risk of weakening the standard established by AP1 and the Rome Statute. A number of states are clearly keen to ensure minimal environmental constraints during their operations but by doing so, the humanitarian imperative for minimising harm is in danger of being lost.

Tackling environmental protection in non-international armed conflicts

Most conflicts are non-international in nature. Non-state armed groups (NSAGs) are therefore responsible for, or associated with, a great deal of wartime environmental damage. Yet states have often been unwilling to address this, an issue summed up brilliantly by Poland, who argued bizarrely that the practice of NSAGs is not relevant to the question of environmental protection in such conflicts.

Objections like Poland’s, and the limited body of judgements of what is typically national case law, have complicated the Special Rapporteur’s work to ensure that the questions raised by NIACs are dealt with in her reports. The lack of law was noted by Vietnam while the ROK felt that applying the draft principles to NIACs would be “challenging”.

Nevertheless, a number of states sensibly welcomed the inclusion of NIACs in the scope of the study, including Croatia, El Salvador, Lebanon, New Zealand, Portugal and Slovenia. Switzerland argued that the environment enjoys general protection in both international and non-international conflicts and specific protection under customary IHL in NIACs. We too recognise the importance of including the topic and urge governments to support its inclusion in a meaningful way. Whether the ILC process will have the flexibility to achieve this is debateable and it highlights serious limitations with the current discourse that must be addressed in future.

Unprincipled objections

The final area where the gulf between progressives and conservatives became clear was during the debate over the wording of the ILC’s draft principles. There is insufficient space to cover this in detail here so only the trends will be discussed. In addition to the principles themselves, which sought to clarify existing treaty and customary obligations with regard to the environment, the idea of protected zones was also suggested by the ILC: “States should designate, by agreement or otherwise, areas of major environmental and cultural importance as protected zones.”

The idea was supported by, or of interest to, El Salvador, Lebanon, the Nordics and Switzerland. Japan were more dubious, Austria wondered how they would be defined, Croatia felt that the idea needed work, Iran suggested that they be WMD free zones and the Netherlands were confused. Singapore felt the concept to be too broad, the UK were doubtful over their legal basis and, finally, the US questioned how they would work in practice and objected to the inclusion of the term “cultural importance”. This was unfortunate as cultural associations with the environment are not just restricted to indigenous peoples but exist in many forms worldwide.

On the draft principles more broadly, the Nordics welcomed them, as did Vietnam. El Salvador felt that they didn’t go far enough while Greece wanted “damage” and “care” to be better defined (comparing IHL’s due regard rule to IEL’s no harm principle). Japan felt they were a fair representation of current IHL and Mexico welcomed them but felt that more work was needed to ensure that they were in accordance with IEL.

Belarus said that more should be done to bring the principles into line with existing IHL, while the ROK wanted to see the supporting commentaries to clarify how the principles of distinction, proportion, precaution and military necessity related to them. The Netherlands also called for more clarity over how military necessity and environmental protection relate to one another. Israel called for modifications to the wording that would have weakened many of the principles, while Malaysia called their publication “premature” without access to the accompanying commentaries from the ILC’s drafting committee. Singapore also called for the commentaries and argued for narrower and “less absolute” principles. The US objected to most of them, largely on the basis that they felt that they went beyond the current applicability of IHL.

We need to talk about conflict and the environment

Once again the debate has served to highlight the significant disparities between states on the question of strengthening the protection for the environment in relation to armed conflicts. All credit to Greece, Portugal, El Salvador, Lebanon, Mexico, the Nordics, Vietnam and many others besides for their supportive interventions.

But, as the number of topics in the debate has grown, it has become harder to identify purely progressive or conservative states, with some strong on some topics but more reluctant on others. National interests are also becoming ever more apparent, such as the US, UK and Israel’s objections to customary law sourced from AP1, to Austria and Mexico’s call for nuclear weapons to be included in the study’s scope – something that may be counterproductive for the purposes of the ILC study.

Beyond the big question of where is this all heading, and the limitations of debate solely within the context of IHL, the very fact that conflict and the environment is being discussed by governments anywhere is incredibly important. Right now the UN Sixth Committee is the only multilateral forum debating the topic – and that only from a legal perspective. On that point, UNEP deserves praise for instigating the ILC process, as do the Special Rapporteur and her researchers for what will eventually be a huge body of work on the topic.

The third report from the ILC, which will cover the post-conflict phase, among other things, will be published next summer and debated this time next year. Progressive governments need to be thinking now about how and where to continue the debate on conflict and the environment and on how they can cooperate to further the objective of greater protection for both the environment and those who depend on it before, during and after armed conflict.

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project