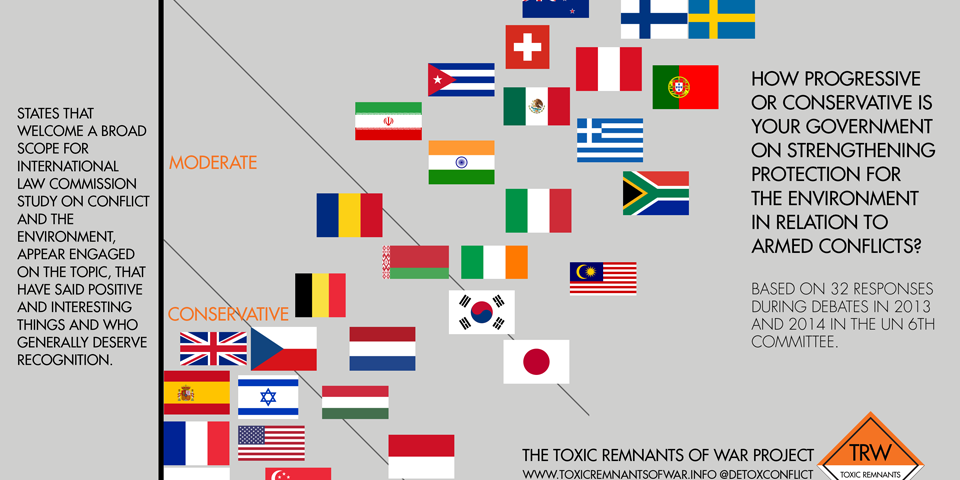

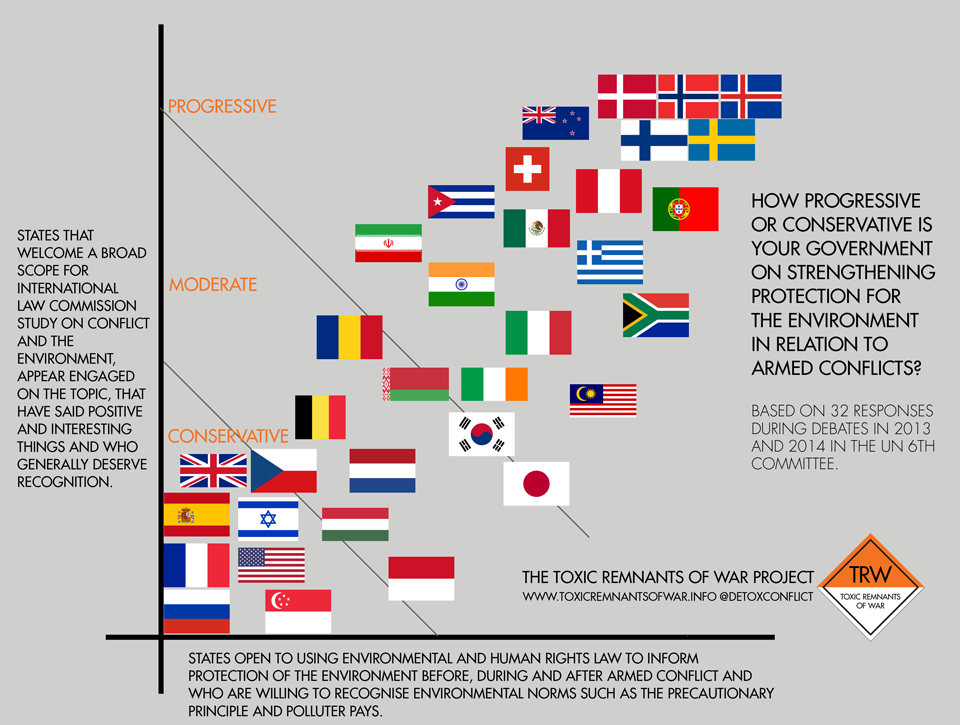

Recent UN debates on the legal framework protecting the environment in relation to armed conflicts have provided a first indication of national positions on the topic.

The first tentative moves to strengthen legal protection for the environment before, during and after armed conflict are underway – and not before time. With everything to play for, we take a look at a scientifically unrepresentative sample of governments to see who’s progressive, and who would rather the international community stuck with a status quo that does little to protect the environment or the civilians who depend on it.

An unscientific cross section of current opinion

In previous blogs, we’ve looked at the distant and more recent history of efforts to strengthen protection of the environment and its dependent civilian population from the impact of warfare. There have been heroes and villains, conflicts and incidents that have acted as policy triggers and geopolitical considerations that have modified state positions and responses. As positions vary over time, it seems important to get the most up to date snapshot possible.

In 2011, the International Law Commission (ILC) launched a five year study on the protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts, appointing Swede Dr Marie Jacobsson as Special Rapporteur. The topic had been suggested by a 2009 report by UNEP, which documented the inadequacy of current legal provisions. The decision to launch the study, its proposed scope and methodology and the first of its three reports were discussed by states in the UN General Assembly’s Sixth Committee in late 2013 and 2014. Dr Jacobsson’s second report has just been published and will be debated in November 2015. Together the reports seek to analyse the law relevant before, during and after armed conflict, with the third report, which will focus on the post-conflict phase, expected in 2016.

The views of governments on the first report, and the process itself, make for interesting reading. It should be noted that the ILC process is not being undertaken with new treaties and conventions in mind, instead only the more delicate proposal of new non-binding guidelines. Dr Jacobsson has also sought to avoid controversy by suggesting that the environmental impacts from the use of weapons be excluded from the study’s scope. Needless to say, the historical and political relationship between nuclear weapons and protection for the environment under Humanitarian Law has not been a happy one.

A total of 32 states commented on the project during the two sessions. Disappointingly, the voices of states that have suffered significant environmental damage from conflict such as Kuwait, Iraq, Serbia, Lebanon, Vietnam, Laos and Afghanistan were absent from the debate, as were African delegations, with the exception of South Africa. Ensuring their voices are heard this year and in any follow up should be a priority for the ILC.

Progressives and conservatives

In spite of there having been only two Sixth Committee meetings, key themes are already developing that are allowing the progressives to be separated out from the conservatives. Conservative states have been quick to reject any changes to the Laws of Armed Conflict (US, UK). They have doubted the utility and feasibility of the process itself (France, Russian Federation, Spain) and have been at pains to reject holistic legal approaches that would see Environmental Law, Human Rights Law or indigenous or refugee rights utilised to inform new standards (US, UK, Israel). As well as opposing the merging of legal regimes, they question whether key principles and norms from Environmental Law such as the Precautionary and Polluter Pays principles have become customary and are at all relevant to the topic (Singapore).

Progressive states are the polar opposite. They welcome the process as long overdue and urgent and call for consideration of the applicability and relevance of parallel legal regimes governing environmental protection and human rights. The TRWP is among many who have argued that such regimes should be raided for guidance on the way ahead and it is pleasing to see this emerging as a key part of the progressive portfolio.

States such as New Zealand and Austria argue that armed conflict should be broadly defined and that concepts like sustainable development are wholly relevant to the project. Switzerland raised the need to clarify the problematically high thresholds for damage under existing IHL, while Japan and others advocated for the consideration of non-international armed conflicts and non-state actors in the scope. Persistent international agitators such as the Nordic bloc, New Zealand and Mexico – who observed that IHL’s environmental provisions were frequently violated – were joined by Portugal, Peru, Malaysia and Greece in backing the initiative. South Africa backed a broad scope while Cuba and New Zealand both suggested a discussion on post-conflict environmental assistance and reparations.

Between these two groups were others who politely welcomed the work of the ILC but offered little else by way of support. The Netherlands, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Indonesia and Belarus took a more neutral line. Iran meanwhile was in favour of post-conflict assistance and tighter controls on the deliberate targeting of oil platforms and, well, peaceful nuclear facilities.

Where is this process leading?

The suggested goal of the ILC process is new non-binding guidelines. It is still early days but the majority of states who expressed an opinion felt that non-binding guidelines were just fine. The Italians, who seemed very supportive of the process as a whole, disappointingly suggested that a handbook might prove a satisfactory endpoint. Unfortunately it hasn’t escaped our attention that a number of states are awash with the hazardous residues from both binding and non-binding guidelines, some are even littered with the remains of the charred pages of handbooks and manuals.

However, one or two states thought it might be an idea to go further. Portugal suggested that the ILC might consider embarking on a “progressive development exercise”, Malaysia raised that with “effective regulation” in 2013 but by 2014 had withdrawn it, settling on a more modest “future guidelines”. The Nordics, who had a great deal to say on the merits of the process itself, were somewhat more reticent on its ultimate aims, although there was much talk of clarifying obligations and the applicability of Environmental Law.

It’s still early days for the process and it will be interesting to see how the debate develops, both this November, and next year after the third report is published. As noted above, ensuring that the voices of states whose environment has been damaged during conflict engage with the debate and are heard is critical. We would also like to see those states with a more progressive outlook work towards a more ambitious outcome for the process. Opportunities like this do not come around very often – around once every twenty years by our reckoning – and it would be a shame to waste it.

Summaries of the Sixth Committee debates are available here (2013) and here (2014).

Doug Weir manages the Toxic Remnants of War Project