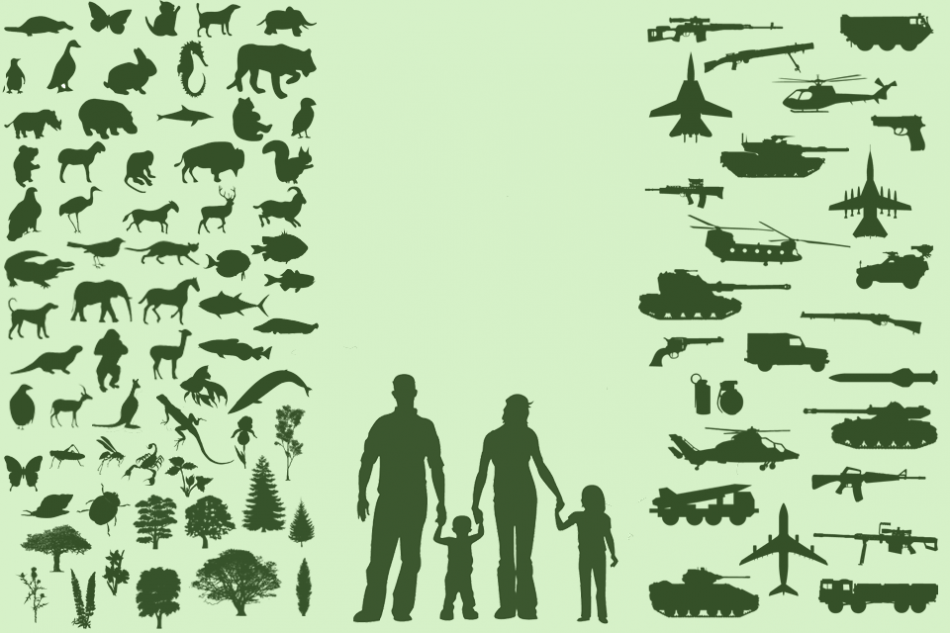

Biodiversity is vital for the stability and security of countries.

Biodiversity hotspots cover just 1.4% of the planet’s surface, yet 80% of major armed conflicts between 1950 and 2000 occurred in these areas. This figure should be striking, but the connections between the environment and conflict continue to be overlooked. With the recent release of a UN report stressing the direct relationship between biodiversity and human rights, Alex Reid asks whether it’s time for us to reassess our understanding of the links between armed conflict, human rights and conservation.

Making the links

In 2010, Lord Robert May asked an unusual question for a world-renowned ecologist: “If some alien version of the Starship Enterprise visited Earth, what might be the visitors’ first question? I think it would be: How many distinct life forms – species – does your planet have?” Lord May suggested that we would embarrass ourselves before our alien guests: we do not yet have the means to accurately measure the number of species populating our planet. What we could confidently tell them, however, is that each species is part of the vibrant ecosystems on which our human rights depend.

The direct connection between human rights and biodiversity is the subject of UN Special Rapporteur Prof. John Knox’s latest report, which was recently delivered to the current session of the UN Human Rights Council. Knox has used his time as Special Rapporteur to drive home the connection between a healthy environment and the attainment of human rights standards, and his latest report focuses specifically on biodiversity’s role in creating and sustaining that environment.

It’s hard to find a more direct challenge to human rights than the immediate violence and displacement that comes from armed conflict. However, Knox’s report should also help draw attention to the more indirect relationship between conflict, biodiversity and human rights.

Over 90% of major armed conflicts between 1950-2000 occurred within countries containing biodiversity hotspots, and more than 80% of these took place within hotspot areas. Thor Hanson, Guggenheim Fellow and independent conservation biologist, suggests that these statistics underscore: “…the urgency of understanding the effects of warfare in the context of biodiversity conservation”, and he’s right.

Biodiversity and human rights

The full enjoyment of human rights afforded by a healthy environment is entirely dependent on the services provided by our local, regional and global ecosystems. These ecosystem services, defined by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment as ‘the benefits people obtain from ecosystems’, can be broken down into four categories:

- Provisioning services, such as food, water, timber and fibre.

- Regulating services which affect climate, floods, disease, and water quality.

- Cultural services associated with the recreational, aesthetic and spiritual benefits of nature.

- Supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis and nutrient cycling on which all other services ultimately depend.

In turn, the health of these ecosystems depends on the richness of their biodiversity. A diverse biosphere is essential to secure the productivity and stability of almost all services, from food and water down to soil formation. The more diverse a biological population, the more disaster-resilient an ecosystem becomes. Greater biodiversity also enables an ecosystem to survive and weather longer-term threats such as climate change.

Drivers of ecosystem degradation: the hidden role of armed conflict

Knox’s report identifies several direct drivers of biodiversity loss, including the over-exploitation of flora and fauna, pollution, invasive alien species and, of course, climate change. However, the direct contribution of armed conflict to all these drivers cannot be ignored. Armed conflict is more than just violence; it also entails societal transformation that changes the way that local and regional communities interact with their environment. This in turn cannot help but have a profound effect on biodiversity.

One clear example of the negative impact of warfare on biodiversity is the mass exodus of more than two million Rwandan refugees following the 1994 genocide into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), Uganda and Tanzania. High demand for firewood among desperately displaced populations with few other resources deforested more than 300km² in the DRC’s Virunga National Park.

Today, the Virunga National Park is an infamous hotbed for the over-exploitation of flora and fauna, including poaching, and a booming charcoal industry. Decades of mineral-funded civil war in the DRC have burdened the resource-rich country, and both the population and the land bear the scars. Studies have also shown that the presence of soldiers and rebels also contributesto deforestation and the bush-meat trade.

Connections between human rights, the environment and armed conflict are of course easier to make in some situations than others. The Niger Delta is classified as one of the top ten most polluted environments in the world, yet it still counts as a biodiversity hotspot because it is populated by a unique range of flora and fauna, hosting up to 60-80% of all the species found in Nigeria. The Delta’s mangrove forest is the largest in Africa, and the third largest in the world, providing food, medicines, and wood for fuel and shelter to the populations residing there. It’s also on the ‘tentative list’ to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Yet conflict and insecurity in the Delta continues to impact its biodiversity and the human rights of its population.

As early as 2001, the African Commission recognised the threat that oil and large-scale water pollution posed to the enjoyment of the human rights of populations in the Niger Delta. The Commission found that the Nigerian government had ‘fallen short of the minimum conduct expected of governments’ by failing to protect the ethnic Ogoni people in the region from the gross environmental degradation caused by oil-extraction.

The belief that the Nigerian government has consistently fallen short of its responsibilities has been shared by armed groups in the Niger Delta for decades. Confrontations between violent movements with environmental grievances resulted in what Michael Watts called a constant cycle of ‘petro-violence’. It is a cycle that cripples the economy of the Nigerian state, and releases huge volumes of oil into a fragile ecosystem through oil-bunkering – a technique used by non-state actors to steal oil to fund rebel activities. Recognising this pattern, the Nigerian government partnered with the UN Environment Programme in 2016 to launch what was hailed as the ‘largest terrestrial clean-up ever seen’, but it could still take more than 25 years before ecosystems are re-established in the Delta.

But conflict’s greatest threat to biodiversity may be a more indirect one: institutional collapse. This runs counter to the common assumption that the more immediate tactical consequences of conflict are the most serious threat to the environment. In research published last year, scholars from UC Berkeley reviewed the ecological, social, and economic pathways that lead to both negative and positive environmental outcomes in conflict. Their study identifies both the direct and indirect ways in which conflict affects the environment, and concludes by suggesting that one of the greatest indirect threats is the brain-drain of talented individuals, including conservationists themselves, from militarised environments.

This is not to say that all conflict is bad for biodiversity. The Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) between North and South Korea is effectively an untouched incubator for biodiversity, on a peninsula which has experienced almost 100 years of continual conflict. One might add that this is precisely because the Korean institutions on each side keep humans at bay – though their motivation is not strictly conservational. Nevertheless, projects that do have an explicit environmental motivation have successfully transformed conflict into conservation. The Sierra del Condor, a mountain range between Peru and Ecuador, is an example of turning a decade long territorial dispute into a peace park, a project partly motivated by bolstering conservation efforts.

Similarly, while altered patterns of human activity associated with displacement from conflicts may have localised benefits – allowing a recovery period for depleted resources – this can come at a high cost for the biodiversity in the areas that populations are displaced to. For example, providing temporary shelter for the displaced can quickly lead to the overuse of local resources.

Cases like the DMZ are the exception rather than the norm, and it’s clear that the positive effects of armed conflict for biodiversity shouldn’t be overstated. UC Berkeley’s study suggested that in 94% of their case studies, at least one pathway in conflict led to negative outcomes for wildlife, whereas only 33% percent showed a positive pathway.

The way forward?

Given the findings of Knox’s report, it’s clear that the importance of biodiversity must be incorporated into the way we discuss and think about human rights. But in so doing, it’s clear that we also have an opportunity to enrich our understanding of the relationship between armed conflict, human rights and the environment.

With more than 90% of major armed conflicts between 1950 and 2000 occurring within countries containing biodiversity hotspots, the way forward should be clear: strengthening environmental protection before, during and after conflict must be a primary goal for both NGOs and governments that support conservation and the protection of human rights. With the sixth mass extinction already underway, the alliance between conservationists and conflict specialists must begin now.

Alex Reid is currently pursuing a master’s in Conflict, Security and Development at King’s College London, with a specialism in environmental issues. She can be found tweeting about the environment and armed conflict at @alexHREID This blog first appeared in The Ecologist.