The threat of an environmental disaster has become weaponised in a dispute between parties to the conflict.

In May 2018, CEOBS reported on the environmental threat posed by an ageing oil tanker moored off the Red Sea coast of Yemen. A year on, the situation remains unresolved and the vessel has now become the subject of a dispute between the Houthis, and the Yemeni government and its backers the Saudi-led coalition. The dispute has escalated during the last two months and may do so further, increasing the threat posed to the marine environment. In this blog, Doug Weir catches up on where things stand, finding that huge questions remain over how the situation can be resolved.

Background

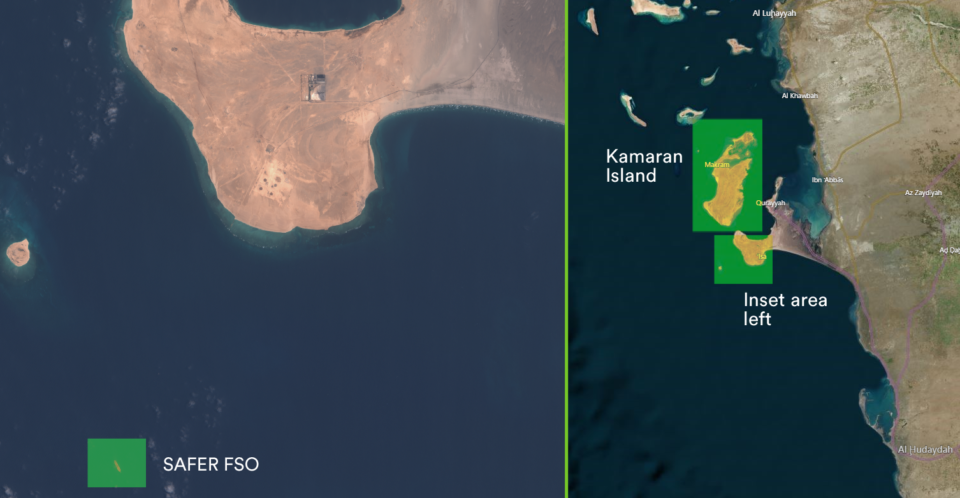

The SAFER FSO is a large oil tanker that has been permanently moored 7km off the Yemeni port of Ras Isa since 1988. A Floating Storage and Offloading (FSO) terminal, it has acted as an offshore platform for vessels loading crude oil from the Marib-Ras Isa pipeline, to which it was connected. SAFER, which owned and ran the FSO, is Yemen’s leading oil company. In early 2015, Houthi forces captured the port and, in the two years that followed, oil operations were scaled back prior to the port’s closure, which was forced by the Saudi-led coalition’s naval blockade and a series of airstrikes on its infrastructure. During that time, the SAFER FSO, which is still thought to contain 1.14m barrels of crude oil, fell into disrepair.

As we reported in our earlier blog, a spill from the vessel could have serious consequences for the marine environment. The notorious Exxon Valdeez disaster involved 260,000 barrels, just a fraction of what the SAFER FSO is believed to contain. And, while the Exxon Valdeez discharged its oil into the cold waters off Alaska, where the breakdown of oil would be slower than in the warm waters of the Red Sea, Ras Isa is close to one of Yemen’s few Marine Protected Areas off nearby Kamaran Island, whose mangroves and coral reefs support local fisheries. A major spill would invariably overwhelm Yemen’s domestic pollution response capacity, and be complicated by the naval security issues in the Red Sea.

What happened next

Our research on the case was triggered by a request for assistance from the Yemeni government to the UN Secretary General in March 2018. In it, the government argued that the vessel was in a “bad and deteriorating situation” and threatened an “imminent environmental and humanitarian catastrophe in the Red Sea”. In August 2018, the United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) posted a tender for a project to assess the safety of the vessel. The background documentation for the tender provided worrying insights into its condition.

The tender confirmed that since the conflict broke out, no maintenance work has been undertaken. As the FSO’s diesel fuel had run out, and not been replaced, its boilers had stopped producing inert gas. FSOs and tankers produce inert gas to fill the voids above the oil in their storage tanks. This is to reduce the risk of explosion from the volatile gases released from the oil they carry. Without replacement, it was thought likely that the tanks would have a significant volume of potentially explosive gases inside. The note also drew attention to the general lack of maintenance, and with it a deterioration in the vessel, its machinery and in its floating oil export hose. It concluded that the “FSO SAFER is an environmental and economic risk that could seriously affect the neighboring countries at the Red Sea coast.”

By the end of August, the tender for the assessment, worth US$317,450, had been awarded to the Singapore-based Asia Offshore Solutions PTE LTD. However, work on the project then stalled. Towards the end of the year, an email from a representative of the Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment’s (ROPME) Marine Emergency Mutual Aid Centre (MEMAC) appeared online, dated November. In it, a Captain John Curley, who had previously led the UNDP’s work salvaging wrecks in the aftermath of the 2003 Iraq War, argued that ROPME – an intergovernmental organisation focusing on marine pollution in the Red Sea area, should instead be given the task as UNOPS “clearly have no experience” in maritime salvage. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are two of the states party to the agreement that established ROPME. It is believed that their proposal had been to tow the FSO to Bahrain for disposal but that this had been rejected by the Houthis.

With a heightened focus on Houthi attacks on oil tankers and the threat of sea mines during late 2018, media interest in the status of the FSO was minimal until mid-December. While UN agencies may have continued to work behind the scenes to get access to Ras Isa for the assessment, there were no public pronouncements to this effect.

Stockholm peace talks create a new dynamic

Matters changed notably as a result of the peace negotiations in Stockholm in mid-December. Phase one of the Stockholm Agreement required both parties to remove their military forces from the ports of Hodeidah, Salif and Ras Isa. The purpose of this “Hodeidah Agreement” was to increase the delivery of humanitarian aid, allow port revenues to be channelled to the Central Bank of Yemen to help pay for public sector salaries and to create a de-escalation strip along the coast. With the removal of the military, local security forces were to take on security duties in accordance with Yemeni law. Implementation of the plan was due to begin early in 2019 and be facilitated by the UN. It is believed that the lifting of the embargo against Houthi oil exports was also on the table in Stockholm but that it was one of several items where agreement couldn’t be reached.

By March this year, the implementation of the Stockholm Agreement remained the subject of negotiation. And, while the ceasefire had reduced the incidence of violence in Hodeidah, it had increased elsewhere in the country. The Houthis remained suspicious of the deal and the focus remained on Hodeidah port given its critical importance as an entry point for food supplies. During this time, there was a spike in fuel prices. This was connected to the Saudi-led coalition’s seizure of tankers bound for Houthi-controlled areas, and new price controls on oil products introduced by the Central Bank of Yemen. The prospect of a military withdrawal from Ras Isa, coupled with the spike in fuel prices, appear to be factors that have influenced the Houthis’ renewed attention on the SAFER FSO, and on its contents.

In early April it was reported that the Houthi Minister of Oil and Minerals, Ahmed Abdullah Dars, had made several requests to the UN for them to lift the export ban on crude oil so that the volume of oil in the SAFER FSO could be reduced, thus, it was argued, reducing the risk it posed. He suggested that, were it not lifted, the UN would be held responsible for any ensuing environmental disaster. Two days later, the Atlantic Council, which is closely aligned with US foreign policy, published an alarmist article on the SAFER FSO entitled “Why the Massive Floating Bomb in the Red Sea Needs Urgent Attention”. The article triggered a flurry of media coverage among the highly polarised regional news outlets.

On April 15th, the UN Security Council held a briefing on the humanitarian situation in Yemen. The UN’s Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock, drew attention to the threat posed by the tanker. This was the first time it had been mentioned in the context of the Security Council. His statement provided some insights into what had been going on behind the scenes: “We have been working with all parties to address this risk, supported by funding from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, starting with a technical assessment. Final approvals for the assessment have been pending since September. We hope that recent indications that a UN project will soon be able to begin work on this critical issue prove correct.”

Matters escalate as attention on the vessel grows

Attention over the fate of the SAFER FSO, and on its contents – around US$80m of light crude oil – grew further on April 26th as Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, President of the Revolutionary Committee of Yemen, tweeted that the Houthis had disconnected the pipeline that connected the FSO with the terminal at Ras Isa. The reasons for doing so are currently unclear. Onshore pipelines have been tapped for oil but doing so with the marine pipeline to the ship seems impractical. In his tweet, al-Houthi said that the Houthis “hold the states of aggression responsible for damage that may affect the marine environment or navigation, which will cause disaster to the world.”

The disconnection was followed with a renewed call from al-Houthi for the UN Security Council to put in place a mechanism for the export and sale of Yemeni crude – including that on the FSO. His proposal was that sales through the mechanism would pay for the importation of refined oil products for the benefit of the Yemeni people, and that proceeds would be deposited in Sana’a and be used to pay public sector salaries. Days later, a spokesperson for the Saudi-led coalition accused the Houthis of putting the environment at risk, while the SAFER oil company itself warned of the risks associated with any attempt to unload the vessel.

With tensions escalating, at the beginning of May both the Yemeni government and the Houthis sought meetings with Lise Grande, the UN’s Resident Coordinator in Yemen. The government urged the UN to pressure the Houthis into allowing access to the vessel, the Houthis reiterated their request that the means be found to unload and sell the oil. The government also raised the issue with the UN’s Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths.

On the 9th May, a spokesperson for Asia Offshore Solutions, which won the contract for the assessment in 2018, said that they hoped to begin work shortly but that they’ve “been waiting for the Hodeidah area to be safe enough for our people to go in”.

Not the end of the story

Should it proceed, the technical assessment of the threat posed by the vessel will presumably help inform what should happen next. What it may not do is to help resolve the political questions over the fate of the FSO and its contents. The extent to which the environmental risks posed by the FSO have been used as political ammunition by both sides, and in particular as a component of the Houthis’ efforts to lift the embargo on oil exports, suggests that finding a solution will remain difficult.

So, what are the options? The Saudi-led coalition’s proposal that it be towed to Bahrain is unlikely to be agreed by the Houthis. Meanwhile, the lifting of the general embargo on oil sales will doubtless be rejected by the Saudi-led coalition, and unilateral efforts by the Houthis to unload the vessel seem fraught with risks. Could the UN make a special case for the FSO and oversee the unloading and sale of the oil, with the proceeds split between both arms of the Central Bank? Or would it be possible to leave the tanker in place and mitigate any risks through restarting maintenance, again overseen by the UN?

A Yemeni economist interviewed by The National suggested that the condition of the vessel meant that it was unlikely that it could be safely offloaded in situ. Abdulwahed Al Obaly argued that the “solution is to tow the Safer to Bahrain” where it can be safely repaired. However, in addition to the political hurdles that need to be overcome, there are also legal and economic questions to be resolved, including managing the insurance, payments for those involved in the work and the fate of the vessel and its oil.

This story still has a long way to go, but it is becoming increasingly urgent that the problem is dealt with. As Mark Lowcock noted in his speech to the Security Council in April, the SAFER FSO is “in poor condition and has had no maintenance since 2015. Without maintenance, we fear that it will rupture or even explode, unleashing an environmental disaster in one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.”

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director.