Could a UN Security Council mechanism to oversee oil sales from the SAFER FSO help prevent a disaster?

For two years warnings have been issued over the serious threat posed by the ageing SAFER oil tanker moored off the coast of Yemen. With a war of words escalating, Doug Weir reviews recent developments, finding that the need for a creative, face-saving solution is more urgent than ever.

More attention but little progress

The SAFER Floating Storage and Offloading (FSO) terminal is a forty-year-old single hulled supertanker moored 7km off the coast of Yemen. Since the Houthis took control of the area in 2015, it has not been inspected or maintained. It is thought to contain at least 1.14m barrels of oil and corrosion and lack of maintenance are creating the conditions for an environmental disaster.

Since we first reported on the threat that the SAFER FSO poses back in April 2018, the fate of the vessel has been a bargaining chip in the stalled peace negotiations, and has been raised with depressing frequency at meetings of the UN Security Council (UNSC). In spite of several false dawns, little progress appears to have been made on the vital first step towards addressing the risks the vessel poses – the Houthis granting access to a UN inspection team to determine its current condition.

In February, the UNSC included a reference to the SAFER FSO in a resolution on Yemen for the first time. The text emphasised ‘the environmental risks and the need, without delay, for access of UN officials to inspect and maintain the Safer oil tanker, which is located in the Houthi-controlled North of Yemen.’ As it is comparatively unusual for specific environmental threats to be addressed in UNSC resolutions, this gives some indication of the attention that council members are now paying to the problem.

Alongside the repeated briefings of UN officials at the UNSC, and the global media attention concern over the SAFER has created, the government of Yemen has continued to publicise the situation. The findings of a report it commissioned into the consequences of a catastrophic accident were circulated in early 2020. These included the humanitarian consequences of the closure of the port of Hodeidah, the impact on food security and livelihoods from pollution on farmland and the devastation of coastal fisheries, and the forced displacement of people from Hodeidah if aid organisations were forced to suspend their operations.

These findings formed the basis of a joint letter to the President of the UNSC a fortnight after it adopted its resolution. The letter was also signed by Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Sudan – Red Sea coastal states with much to lose. Yemeni officials and embassies have persistently highlighted the issue on social media and in press briefings. The SAFER has also featured in statements by the UK and other governments.

On May 23rd it was the focus of a tweet from the US embassy to Yemen, which observed that ‘for years, the Houthis have prevented international experts from assessing it. They must permit inspection and remediation, before it’s too late.’ The US embassy tweet appears to have triggered a response from Mohamed Al-Houthis, who is close to the Houthi leadership and who accused the US and its allies of “caring more about shrimp life than Yemeni lives”.

Gaming the blame

A piece published on the Houthis’ website soon afterwards doubled down on the communications strategy that the Houthis have been pursuing for months: the Saudi-led coalition would be wholly responsible for any ensuing catastrophe. It reported that Mohammed Abdulsalam, the head of the Houthis National Delegation, had tweeted that: “From an early stage, we have been calling for the maintenance of the Safer tanker, but the US-backed forces of aggression have deliberately, with its unjust siege, put obstacles and prevented any maintenance.”

The primary obstacle he highlights would appear to be the sanctions preventing the Houthis from selling the contents of the SAFER, although it is unclear why this should prevent an inspection and maintenance of the vessel. In April 2019, Al-Houthis had called for this to be addressed, calling on “the UN and the Security Council to put in place a mechanism to sell Yemeni crude oil, including the oil in the (floating storage tank).” At the time, Brent crude was at $71.23 a barrel, today it is at $27.64. What was worth around $81.2m, has now fallen to $31.5m.

Meanwhile the article also explained that the Houthis’ foreign minister, Hisham Sharaf Abdullah had told the Saba News Agency that the [Houthi] ‘authorities in Sana’a had previously requested more than once from the United Nations, its organizations and specialized agencies in Yemen to send an evaluation and maintenance team to the floating oil tank, Safer, to assess the situation and perform the required maintenance.’

This claim stands at odds with the reporting of UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the UNSC. In January it reported that it had been “encouraged that senior Ansar Allah [Houthis] officials recently agreed – without conditions – to the assessment of the SAFER oil tanker… so we were disappointed when other Ansar Allah officials later reversed this position. We are following up with the authorities now to confirm how we might proceed.”

The Houthis wish to use the proceeds from the sale of the SAFER’s contents to boost their coffers, and the vessel and the threat it poses as political leverage. In the meantime, their response to the escalating international pressure over their refusal to grant access to the UN is to promote their own blame narrative. It is unclear whether their apparent lack of internal consensus over granting access is genuine, or whether it merely allows them to promote the pretence of cooperation.

What’s at stake in this escalating war of words

The likelihood of an adequate response to a serious spill from the SAFER was always remote. The logistical and financial constraints that the COVID-19 pandemic has created has lessened that even further. Efforts to predict the environmental and economic consequences of a major spill have been undertaken by Dr Ian Ralby and colleagues at IR Consilium. We very much echo their conclusion that a serious incident would lead to an environmental and humanitarian disaster, and one that would affect a country that is already in the grip of the world’s worst humanitarian crisis.

The consequences of a serious incident are such that it is difficult to understand why so little progress has been made. Part of the problem lies in the fact that the SAFER’s fate has become tied up in the wider politics of the conflict as a bargaining chip. But the lack of neutral state actors in a conflict that has become internationalised is also problematic. Because of this, stakeholders should proceed with caution to avoid amplifying a blame game that will do little to resolve the threat the SAFER poses. As research in eastern Ukraine has shown, politicising environmental threats in conflicts can undermine the opportunities they can create for cooperation.

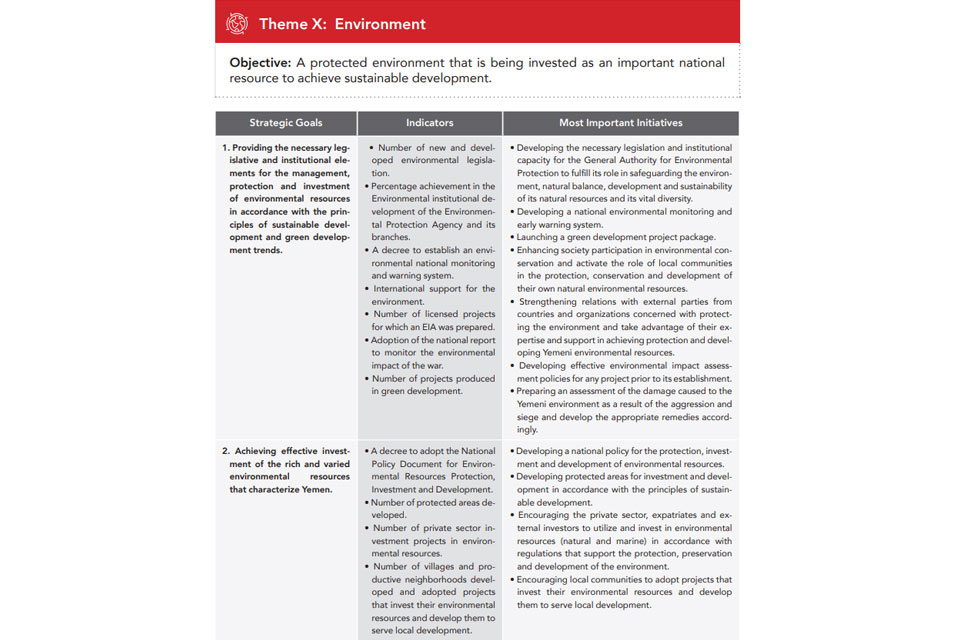

In March 2019, the Houthis published their ‘National Vision For The Modern Yemeni State’. This manifesto outlined their aspirations for statehood in detail. The vision contains detailed objectives for governance and development, and also addresses environmental protection. It seeks to achieve ‘A protected environment that is being invested as an important national resource to achieve sustainable development’.

While this may just be glossy public relations spin, it speaks to a wider question that the Houthis must face up to. Allowing, and being seen to have allowed the SAFER to devastate the economy and ecology of the Red Sea coast would be long-remembered as an abject failure of environmental governance. Moreover, the SAFER’s value is not just in the oil it contains, it was also a key component of Yemen’s pre-conflict oil export infrastructure. As such its long-term strategic and economic value to a future Houthi state would count for little in the event of a major incident.

Seeking solutions

The complex dynamics of the conflict in Yemen are changing, and there is perhaps increasing scope for creative solutions to address the SAFER. These will need to be led by the UN and will also need to balance the competing demands of the Houthis and the Yemeni government. One of the few ways this could be approached is for the UNSC to create a specific mechanism to oversee and manage the sale of the SAFER’s contents.

Although this would be desperately unpopular – and potentially be rejected by the Houthis for not addressing all oil sales from the areas they hold – it could be presented as a specific response to a very specific threat. It would also allow each side to save face. The proceeds from any sale – once the salvage costs are accounted for – should not go to either of the conflict parties but instead be managed by the UN to provide humanitarian aid to the Yemeni people. In doing so making a modest contribution to the current humanitarian aid budget, which as of this month is only 15% funded. The mechanism and process should be fully transparent and time-limited, to ensure that it proceeds and is concluded as swiftly as possible.

This does of course assume that the SAFER is still safe to board, and safe to unload in situ. Determining both will first require that the Houthis cease obstructing a UN technical assessment of the vessel. And, while brokering a deal with the Houthis will prove unpalatable to many governments, there is surely an overwhelming regional and global interest in preventing an oil spill disaster in the Red Sea – a spill that would further exacerbate Yemen’s humanitarian crisis.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director