Report: Protected area conservation in Yemen’s conflict

Published: July, 2021 · Categories: Publications, Yemen

Overview

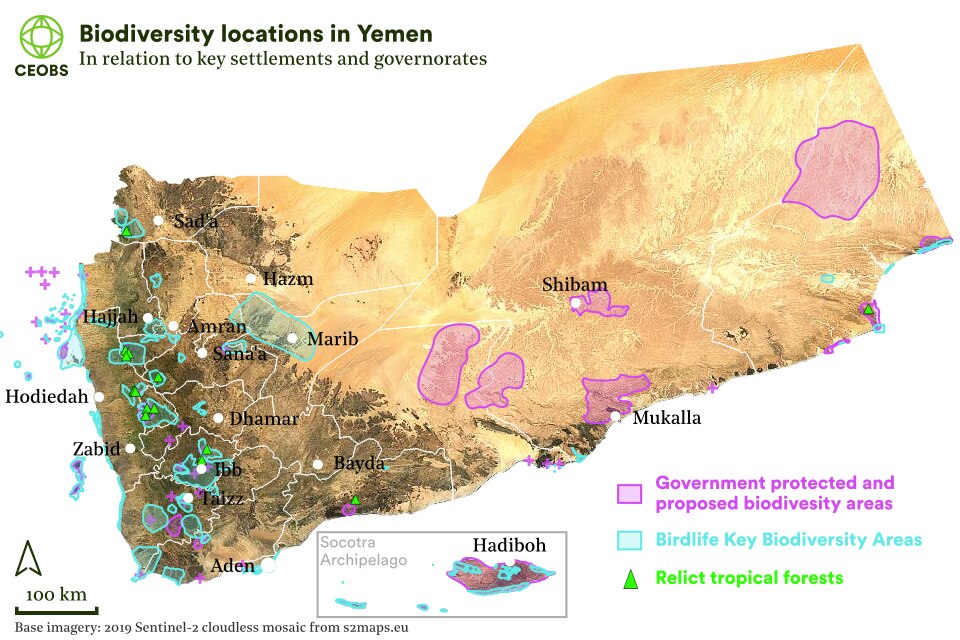

Biodiversity and flourishing ecosystems have an intrinsic value, but they also underpin livelihoods and local economies, contribute to food and water security and help mitigate the effects of climatic extremes. Yemen’s geological history, diverse landscapes and climate have created a range of habitats and a rich – and in places unique – diversity of terrestrial and marine species.

Historic efforts to protect key biodiversity areas in Yemen have met with limited success. Donor funded projects often failed to take the needs of communities into account, while limited government capacity and weak governance meant that many protected areas enjoyed little protection.

This report assesses the impact that the conflict has had on five of Yemen’s protected areas. In doing so it examines a range of underlying dynamics relevant to area-based conservation in Yemen, and during armed conflicts elsewhere.

Key findings

- The protected areas we assessed are primarily threatened by indirect drivers of environmental degradation, rather than direct conflict-linked damage.

- Nationally important relict valley forests in Yemen’s western mountains appear to be under stress from deforestation linked to the conflict.

- The Socotra archipelago is threatened by accelerating and unsustainable development pressures, political instability, increasing militarisation and illegal fishing.

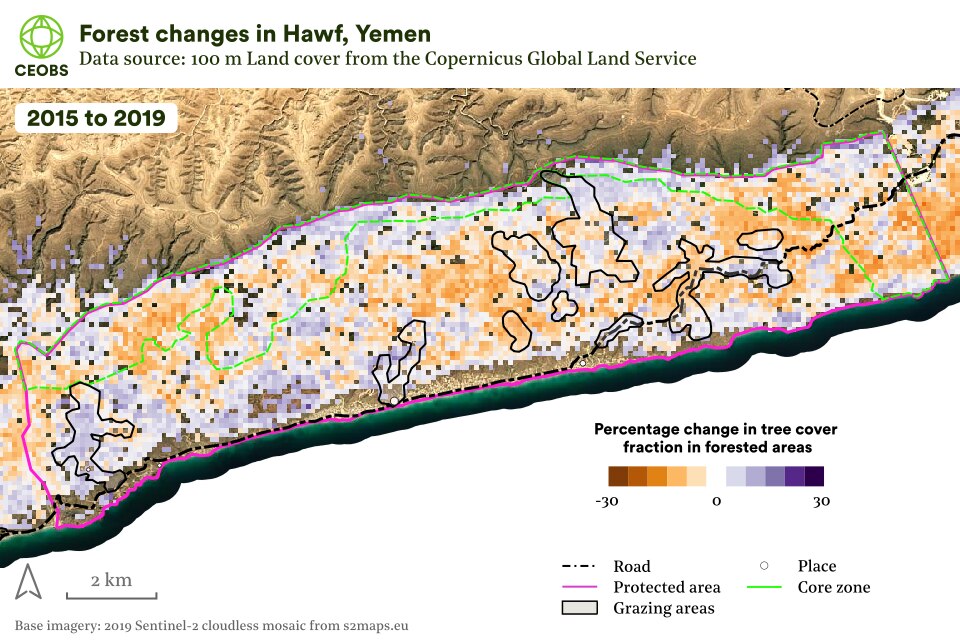

- There have been marked changes in woodland and vegetation cover in the Hawf protected area in Yemen’s south east but field research is needed to determine the implications for biodiversity.

- Aden’s only nature reserve has been heavily impacted by neglect.

- The conflict has impeded the planned establishment of marine protected areas, while the FSO SAFER oil tanker crisis is placing one of its most important marine areas at risk.

Contents

1. Yemen’s protected areas

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines a protected area as ‘a clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values.’ We’re more familiar with them as nature reserves, or national parks.

Prior to the current conflict, Yemen had just 10 terrestrial and marine areas designated as protected areas, amounting to 0.77% of its terrestrial, and 0.44% of its marine ecosystems. These ranged from an urban wetland, to the Socotra archipelago with its unique biodiversity and culture, which was granted World Heritage Status by UNESCO in 2008. However, the protections afforded to these sites was limited, with many existing only on paper.

Conservation in Yemen faced numerous barriers. Underdevelopment, high levels of corruption, recurring periods of political instability and a lack of institutional capacity all played a role. But so too did donor programmes that failed to take the local context into account, or reflect the needs of local communities. Meanwhile Yemen’s growing population was placing increasing demands on its natural resources even as conservationists raced to map them.

The ongoing insecurity in Yemen has impeded field research to properly quantify changes in biodiversity linked to the conflict. Yemeni researchers often worked in collaboration with international specialists to catalogue species, identify trends in habitat loss or to develop protected area governance. As access has decreased, particularly in areas where insecurity has been most acute, so data on biodiversity trends has become more difficult to obtain.

This places a greater onus on remote data collection techniques. We have used remote sensing products to identify trends in land cover change during the conflict. This is used as a proxy for overall ecosystem health, and has been supplemented by satellite imagery, official reports, academic papers, expert interviews and social and traditional media reporting. What follows is not intended as a comprehensive analysis but instead seeks to draw out narratives linked to the conflict and which are of relevance to biodiversity protection in Yemen, and in other conflicts.

Conflicts and biodiversity

There are examples of where armed conflicts can prevent biodiversity loss, primarily through reducing human access to particular areas. For example, by the presence of minefields, by displacing human populations or through constraining economic development that might otherwise have taken place. However, in most cases conflicts hasten biodiversity loss by stripping away or retarding environmental governance, by curtailing international assistance programmes, by turbocharging pre-existing environmental pressures or by creating new threats to ecosystems.

Few protected areas are wildernesses free from human influence. Many areas enjoying protected status are utilised by people for their resources, and in many cases, ecosystems have developed alongside agricultural or resource harvesting practices for hundreds of years. This is certainly the case for Yemen. The societal changes wrought by conflicts can, and often do, disrupt the balance of these relationships. Nor does peace necessarily bring a halt to biodiversity loss. Peace can create new pressures over land and resource use, pressures that states recovering from conflict are often poorly equipped to manage.

Yemen’s biodiversity

Lying at the junction of three of the Earth’s major biogeographic zones – the Palearctic, Afrotropical and Oriental, and with a highly varied landscape, Yemen is rich in terrestrial biodiversity. Prior to 2015, between 13 and 15 million people in rural areas were directly dependent on natural resources for energy, food, fodder, traditional medicines and building materials. The loss of biodiversity therefore has a direct bearing on livelihoods, particularly those of the rural poor. As well as providing natural products for communities, when healthy, ecosystems such as woodlands help regulate local climates, water transport and storage, and prevent soil erosion, in turn supporting agriculture, and food and water security. Yemen has been repeatedly hit by severe flash floods in recent years, and it has been predicted that it will face increasingly intense and unpredictable rainfall patterns as the climate warms.

Just 3% of Yemen’s land area is suitable for agriculture. Historically this was often concentrated along the course of ephemeral rivers – wadis – on its coastal plains or, further inland, on man-made terraces on hillsides. Rangelands, forests and woodlands cover another 40% of Yemen, while the remaining 57% is mainly desert. Prior to its current conflict, Yemen’s low economic development, prolonged political instability and its vulnerability to climatic shocks had made it the focus of assistance from international organisations. In light of biodiversity’s critical importance for livelihoods and resilience, a number of these initiatives had focused on this alongside sustainable development, with the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and others providing capacity building support within the framework of the UN Convention on Biodiversity.

With international support, Yemen had become party to a number of Multilateral Environmental Agreements and developed its domestic environmental law. However, its capacity to implement environmental legislation was weak, and governance was fragmented. The situation was made more problematic by a range of direct and societal pressures. These pressures included deforestation, the over-extraction of water resources, pollution, soil loss, rapid population growth and poverty.

Some efforts to identify key biodiversity areas containing unique, or nationally or regionally important ecosystems and species have been undertaken in Yemen but remain incomplete. Meanwhile, initiatives to promote community-based management of protected areas have often been poorly designed or implemented. Ecosystems designated as protected but which in reality have lacked coherent protection include woodlands, marshlands and wadis.

The primary focus of international conservation assistance has been Yemen’s Socotra archipelago in the Indian ocean. Its four islands and two islets feature unique biodiversity of universal importance, with 37% of its plant species, 90% of its reptile species and 95% of its snail species found nowhere else on Earth. Prior to the current conflict this “Galapagos of the Indian Ocean” was seeking to balance growing eco-tourism and development with environmental sustainability, with limited success. Socotra’s main island is also home to Yemen’s only wetland designated as internationally important under the Ramsar convention: the Detwah Lagoon.

2. Five protected areas and their stories

We selected five of Yemen’s protected areas for study, and in light of the limitations of the methodologies that we have used, our findings should only be viewed as indicative. Most of these sites face multiple pressures but we have focused on drawing out narratives for each area that provide insights into the often-complex relationships between armed conflicts and area-based conservation.

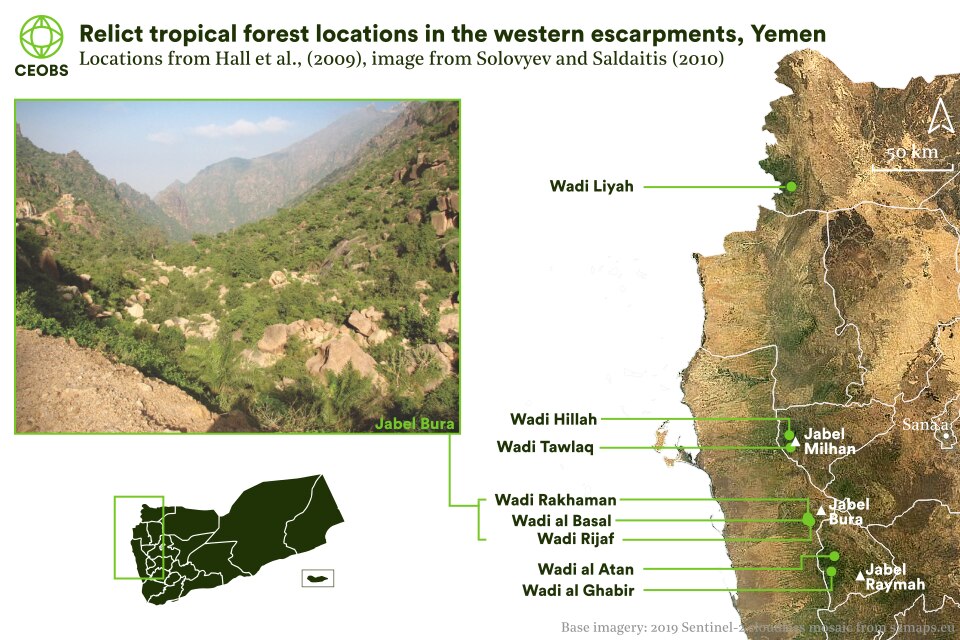

2.1 Jabel Bura’a – relict tropical forests at risk

High levels of deforestation have been reported across Yemen, as reliance on fuelwood has increased as a coping strategy in response to the economic conditions in the country. Firewood collection and charcoal production is often focused on acacia woodland. While clear cutting of woodland can be tracked remotely, the extent of cropping, the felling of individual trees, and the collection of fallen wood is more difficult to monitor remotely.

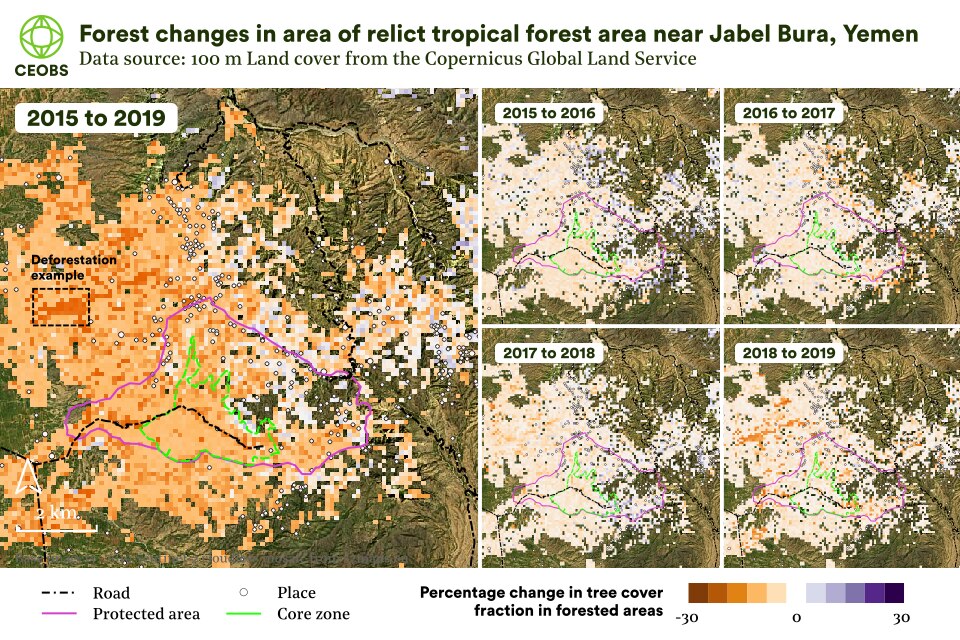

Yemen has extensive scrub woodland, but Jabel Bura’a – a small national park in Yemen’s Red Sea coastal mountains, 70 km east of the port city of Hodeidah – is home to a fragment of tropical forest. These forests were far more widespread across the Arabian Peninsula when its climate was wetter than today. It is not the only fragment in Yemen. Six further localities have been identified, but when the park was established in 2005 the Bura’a was the largest and most intact. These relict forests are important sites for plant species unique to Yemen, and are part of a mosaic of valley vegetation types influenced by altitude and proximity to the wadi channels that support them.1 In 2011, the area around the park was designated as a biosphere reserve by UNESCO, recognising the important interplay of its cultural and biological heritage.

Prior to 2015, the park’s rare forests were threatened by the expansion of agriculture, the overharvesting of firewood and overgrazing by goats and camels. The upgrading and widening of the road accessing the valley in 2004 had already caused irreparable damage to 13% of the most important forest area. The road had also facilitated increased visitor numbers. Management of the Bura’a was supposed to have been decentralised to the local community but poor planning and implementation had instead led to disputes.

Figure 2. Many of the relict valley forests of Yemen’s western mountains lie close to areas that have experienced intense conflict and significant population displacement since 2015. Image of Jabel Bura from Solovyev and Saldaitis (2010).

The valley forest fragments are clustered in four geographically isolated areas. We looked at four of these clusters. To the north, close to the Saudi border, lies Wadi Liyah. Due east of Ras Lanuf, and on the western flanks of Jabel Milhan are Wadi Hillah and Wadi Tawlaq. And, 80 km to the south east, and inland from the port of Hodeidah, the cluster in and around Jabel Bura’a and the wadis Rakhaman and Al Basal, which lie just outside the park’s northern boundary. Further south, we looked at two further wadi forests close to Jabel Raymah.

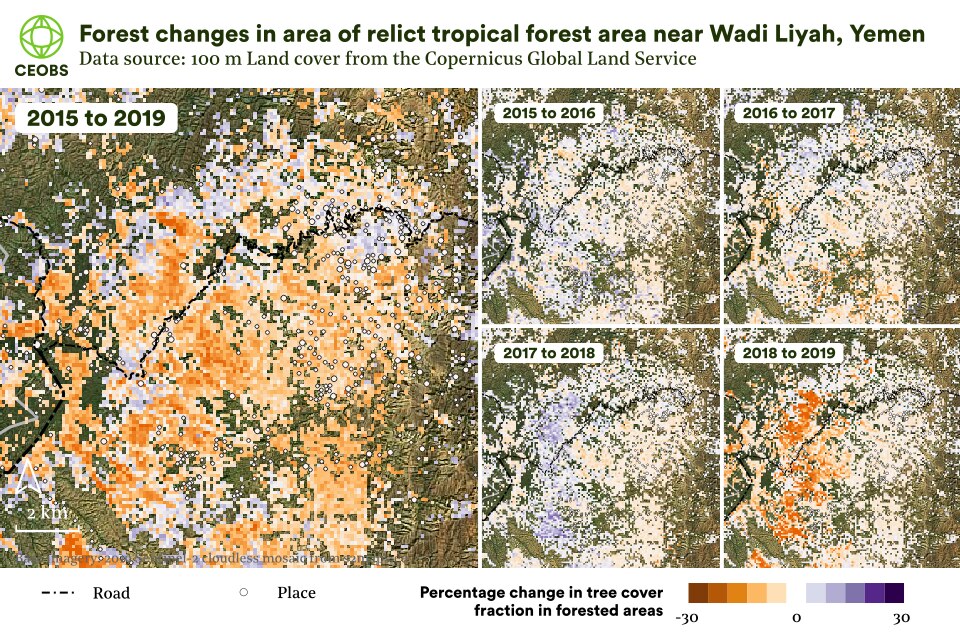

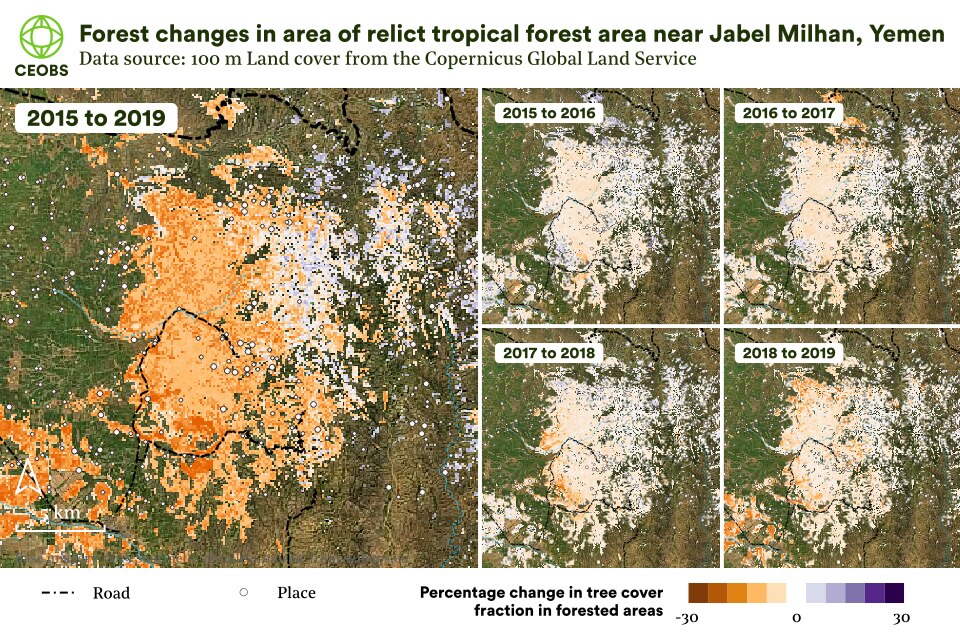

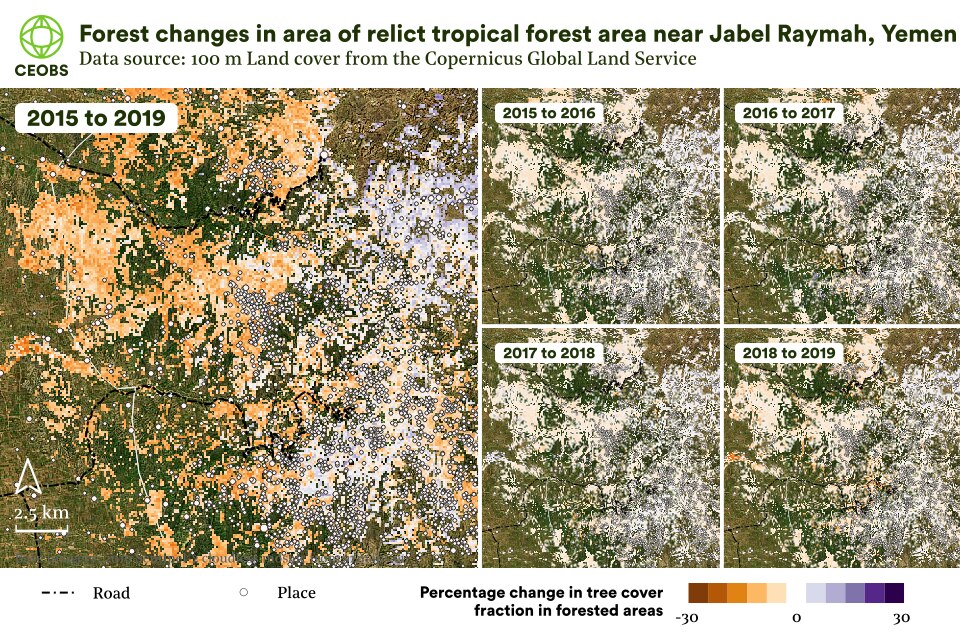

To examine the changes to these relict forests, we used annual global land cover change maps from 2015-2019. Figure 3 shows the percentage change in the fraction of tree cover, both annually and over the whole period. The pattern of tree cover decline is clear across the relict forest areas. In Jabel Bura, Jabel Raymah and Jabel Milhan this decline is gradual, year on year. However, in Wadi Liyah, the changes occur predominantly in 2019.

Figure 3. Percentage change in tree cover fraction for selected relict tropical forest areas in Yemen over the 2015-2019 period. Forest cover fraction data from the Copernicus Land Monitoring Service annual global 100m Land Cover Change Version 3.0.

It should be noted that these land change maps are a global product and can suffer from significant uncertainty at a local scale – as such these findings are preliminary and ought to be confirmed with a higher-resolution analysis, ideally using ground verified training data. This land use methodology was employed to negate for the confounding influence of the greening of natural vegetation across Yemen, either due to CO2 fertilisation, or climatic changes.2

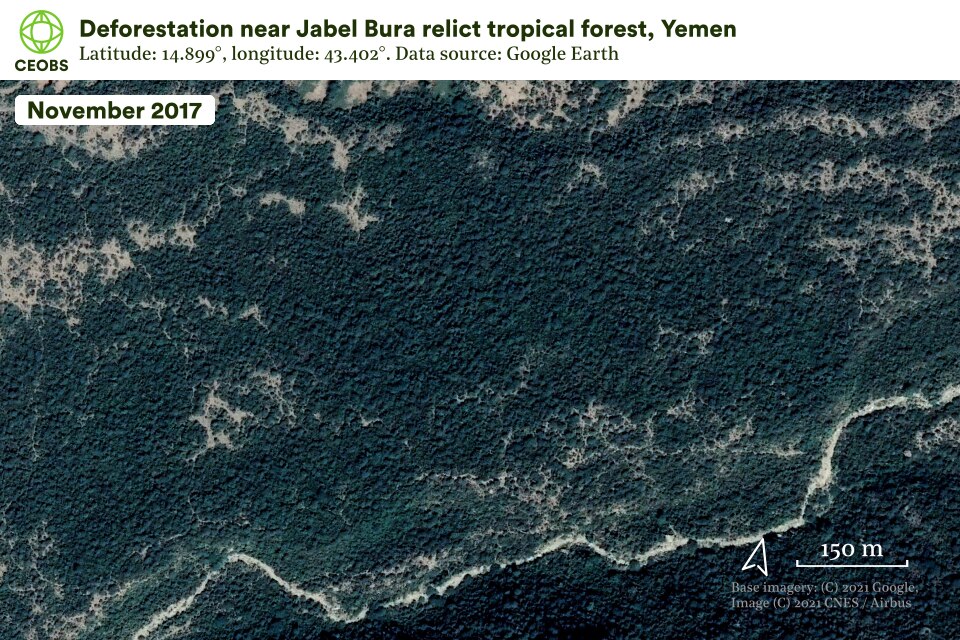

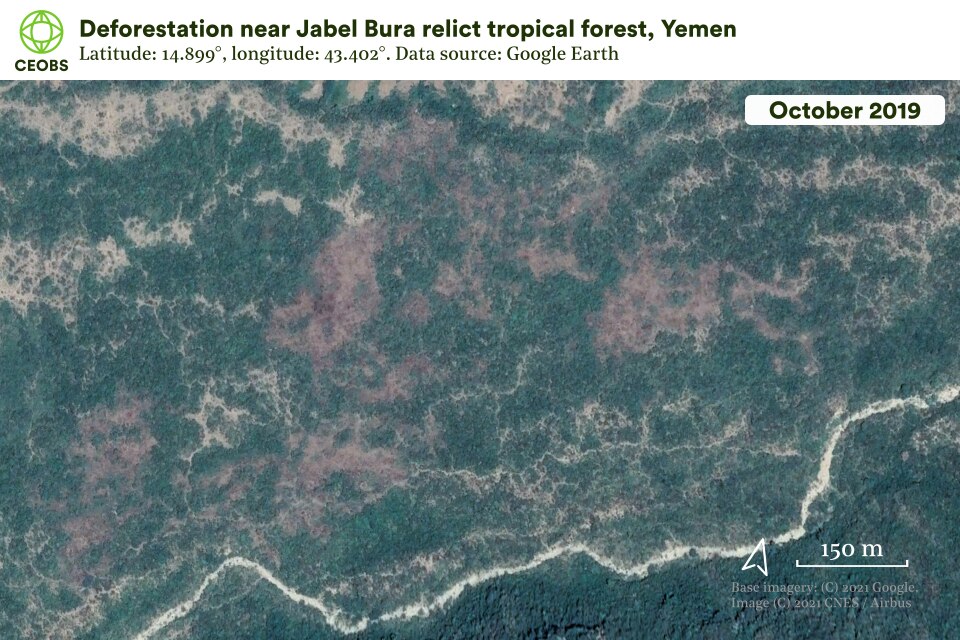

Figure 4. Deforestation outside the Jabel Bura protected area. For the location of this imagery see the third image in Figure 3’s carousel.

Should our analysis be accurate, and given the overarching trend of increased deforestation across Yemen, it seems likely that overharvesting is the primary driver of the losses we have identified. The increased cost and decreased availability of oil products caused by the conflict has seen a nationwide shift to charcoal and firewood for cooking and heating, and it may be the impact of this coping strategy that we are picking up in the satellite data.

2.2 Hawf – a unique fog driven forest

Hawf is situated in the far east of Yemen and comprises a unique fog-driven ecosystem, which was designated as protected in 2005. From June to September, moisture-laden monsoon winds envelop coastal cliffs, which reach 1,400 m above sea level. These support a relict deciduous forest, rich in plant life, which in turn is home to a wide variety of mammal species, several of which are critically endangered, such as the Arabian leopard and Nubian ibex. A 2021 investigation by the Yemeni environmental platform Holm Akhdar found that hunting of such species had increased across the country during the conflict. Hawf’s ecosystem is part of a transboundary area that links up with that of the Dhofar Mountains in neighbouring Oman, against which the park abuts.

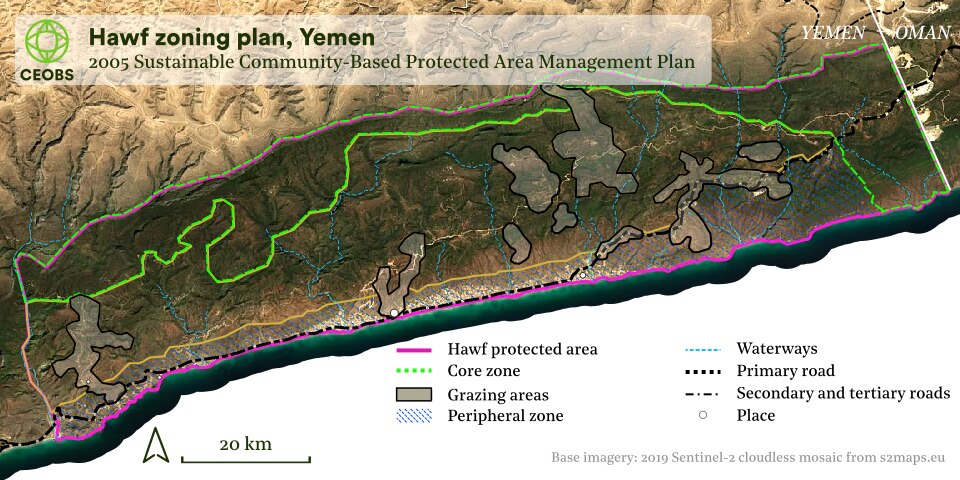

Figure 5. The proposed zoning plan for the Hawf protected area, south-eastern Yemen, which sought to balance sustainable land use with conservation. From Schlecht et al 2015. As of 2015, implementation of the plan was reported to have been limited.

For hundreds of years, the communities now within the protected area reared livestock using the mahjeem system. Goats and camels were grazed at higher altitudes during the wettest season, which allowed for natural regeneration of the woodland below. This system had begun to break down in recent years, with populations of both people and livestock increasing. Development also brought new pressures such as hunting, solid waste disposal and the overharvesting of wood. Proposals to formalise community-based conservation measures had been floated but not implemented. A study published in 2014 found that awareness of the government’s decree designating the area as protected was limited, and proposed a number of ways in which conservation measures could complement and support local livelihoods.

Our research indicates that areas of the park have seen forest loss over the duration of the conflict, although in some areas there have been gains. As with the Bura’a analysis above, these results should be viewed as preliminary.

However, analysing forest cover alone does not tell the whole story, with field studies required to determine how different plant and animal species are faring below the canopy. In spite of its distance from the focus of the fighting in northern and western Yemen, the conflict has impeded biodiversity initiatives in the area, even for local conservation organisations. One local expert has suggested that extended droughts and invasive plant species have also contributed to a deterioration of local biodiversity.

Our analysis of tree cover dynamics during the conflict reveals a mixed and complex picture, with changes in woodland density varying across the protected area, as well as in its core zone.

Alongside an increasingly unpredictably climate, which may impact the fogs that feed it, the greatest threat Hawf faces may be weak governance. It has remained attractive for visitors during the conflict but park management is under-developed. There have been complaints of littering, poaching and of fires. Concerned by the growing footprint of visitors in the absence of an effective governance system, some in the community are opposed to the establishment of tourist infrastructure. They argue that its development without a clear management strategy and robust authority would risk further damage to the area. Other local experts have urged the community to work to protect Hawf and, in 2019, a civil society forum was established with that objective.

Its timing was no accident. From 2017 Saudi Arabia sought to expand its influence in Al Mahra, an area it contests with the UAE and neighbouring Oman, under whose sphere of influence it has historically fallen. The Saudis control its airport, and now have 20 bases and outposts in the area. They were alleged to have planned one in the reserve, and in February 2019 community leaders demanded a halt to their activities.

The growing risk of securitisation in Hawf may have increased the sense of community ownership of the park, but it has also created new obstacles for wildlife. For example, the strengthened border fence separating Yemen from Oman has restricted the movement of animal species between Hawf and the Dhofar. The last two years have also seen significant development at the now Saudi-run border post, and with it the building of a steep hairpin road up the escarpment, which has cut a swath through the woodland.

Neighbouring Dhofar provides a vision of one potential future for Hawf. In the last three decades, roadbuilding, and with it increased access and economic development, have led to overgrazing, bringing changes to its flora and habitat degradation. With peace, and absent an effective system of protection, Hawf risks suffering the same fate.

2.3 Socotra archipelago – a threatened World Heritage Site

The Socotra Archipelago is around 350 km south of Yemen in the Arabian Sea. Its islands are a UNESCO World Heritage Site, thanks to its combination of unique wildlife and culture. A continental fragment separated from Africa for millions of years, it has high levels of endemism and the archipelago is one of the world’s major island biodiversity hotspots. As a result of its scientific importance and international status, for decades it has been a priority for international donors and for biodiversity protection.

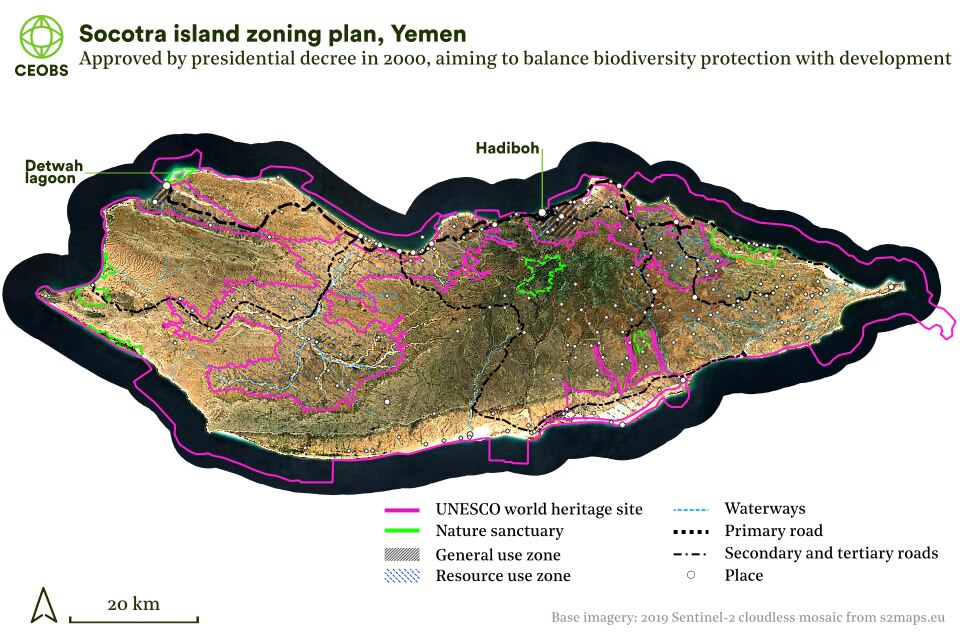

Figure 7. Socotra’s zoning plan was established by presidential decree in 2000. Its aim was to allow the sustainable development of Socotra while protecting the archipelago’s unique biodiversity. It divided the islands into Resource Use Reserves, General Use Zones and Nature Sanctuaries.

Although Socotra’s political independence has increased in recent decades – it ceased being administered from the mainland and became a governorate in 2013 – it has still been affected by the domestic and regional politics of the conflict. Matters escalated in 2018 when the internationally recognised Yemeni government confronted the UAE, which had been extending its influence on Socotra for several years.

The UAE views Socotra partly as a tourist development opportunity, and partly as a strategic aircraft carrier, supporting its wider regional objective to control shipping and trade routes. This security policy has also included occupying Mayun Island in the Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and developing an air base there. In common with their wider strategy for southern Yemen, the Saudis have also sought to consolidate their influence on Socotra, through both development assistance and political interventions. Following growing political unrest, in June 2020, the UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council took full control of Socotra.

Together, increasing political instability, the UAE and Saudi Arabia’s infrastructure and development funding, weak governance, recurring cyclones and isolation from international conservation expertise and programmes are placing Socotra’s unique biodiversity under pressure.

External influence

Tensions had long been present over the extent to which outsiders were determining Socotra’s development, with some objecting to the conservation regulations being imposed as a result of its UNESCO World Heritage status. As the conflict has gone on, UNESCO’s focus has changed from implementing strategic regulation, to one of emergency responses. This shift is readily apparent in UNESCO’s exchanges on Socotra with the government of Yemen since 2013. It should be noted that UNESCO does not implement programmes on the ground, this remains the responsibility of national governments.

In the wake of the Arab Spring, it was acknowledged that Yemen was enduring a “challenging period”. This had delayed implementation of both the government’s own decrees, which included the establishment of an independent management authority for Socotra, and recommendations from an IUCN fact-finding mission to the archipelago in 2012.

As the conflict escalated in 2015, concern was expressed at the vulnerability of Socotra due to the deteriorating security situation. It was also noted that the government had failed to report on progress towards addressing threats that had already been identified. These included incomplete legal frameworks, governance and management systems, roadbuilding projects and overgrazing, invasive alien species, overfishing and the collection of marine resources, and solid waste management. We undertook a remote assessment of road building while preparing this report. While building surged in the period up to 2010, our analysis suggested that these damaging projects had not continued between 2015 and 2020.

By 2017, concern over the UAE’s development spending had emerged. A sea port had been expanded, rather than just repaired, and UNESCO was requesting information on not only development projects but also alleged military operations. A year later, security constraints continued to prevent the deployment of an international monitoring mission and UNESCO was expressing its “utmost concern” about multiple threats to Socotra’s Outstanding Universal Value. These included uncontrolled developments, unsustainable resource use and the absence of biosecurity to prevent the importation of invasive alien species. The presence of the invasive red palm weevil was formally confirmed in June 2020. Although Socotra has no endemic palm species, the weevils threaten the livelihoods of Socotri date producers. Invasive species are closely linked with development, as they hitch a ride on imported goods.

Aujourd'hui, un éboueur de #Socotra m'a envoyé ces photos catastrophiques de décharges sauvages. Depuis le coup d'Etat de l'an dernier, les éboueurs n'ont plus les moyens matériel pour travailler.

…soon. pic.twitter.com/8dTDosetkA

— Quentin M. (@MllerQuentin) May 5, 2021

قال مدير صندوق النظافة والتحسين في المحافظة أحمد صالح، في حوارٍ مع "قشن برس" إن من أسباب تراكم النفايات انقلاب الانتقالي وتنصله عن دعم الصندوق لمواصلة أعماله، وعدم تمكينه من توظيف إيراداته المودعة في البنك، في الرابط أدناه تفاصيل الحوار: https://t.co/Xf585AjQ4E…#قشن_برس#اليمن pic.twitter.com/9dgRMNoxeR

— قشن برس – Qishn Press (@QishnPress) May 24, 2021

Tweets highlighting the growing solid waste management crisis on Socotra, and the impact of plastic pollution on its shores. In 2020, the island’s governor called for financial assistance to help tackle the problem.

A 2021 investigation by Holm Akhdar suggested that the UAE-backed authorities are having an increasingly undue influence on the independence of the Socotra branch of the government’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). To date, little detail has been forthcoming from the EPA on the concerns being expressed by UNESCO, with its review panel noting that “…the report provides no information to ascertain the overall state of the property’s natural resources or management”. This includes the environmental impact of development projects. UNESCO still argues that security and logistical constraints are preventing monitoring visits to assess the situation first hand.

This month, the delayed 44th session of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee will consider a decision that could open the door to Socotra being placed on its list of World Heritage Sites in Danger. The Committee will demand far more information than has hitherto been forthcoming from the EPA over the scale of development on the island. But how did it reach the point where Socotra’s addition to the list looked likely?

Flawed programmes and weak governance

The problems pre-date the current conflict. Between 2001-08, a UNDP project backed by international donors sought to implement a presidential decree establishing a conservation and zoning plan for the islands. The plan would demarcate protected areas, and those where controlled development could take place. The Socotra EPA grew to more than 100 staff. And in 2008, five government decrees were passed, establishing the legal framework for the protection, management and sustainable development of the archipelago. But, following the closure of the UNDP’s project, the EPA’s financial resources and capacity dwindled, and progress towards the plan for Socotra stalled. By 2012, the IUCN reported that the Socotra EPA’s annual budget was just US$5,000. At its peak, EPA salaries had far exceeded those of the most Socotris, distorting the local economy.

It wasn’t just down to a lack of sustainable funding. In 2013, a review into the design of a still ongoing UNEP follow-up programme argued that: “the poor performance of projects has probably been because they failed to address the major barriers to conservation in the Yemen: poverty, poor livelihoods and inability to address stakeholders’ needs.” And, while community associations established by the UNDP project did continue to function, the instability that followed 2011 only served to increase pressure on the archipelago’s biodiversity. Huge sums had been expended but there had been a failure to translate this into long-term conservation capacity.

Between 2008-19, UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee made 31 recommendations for measures to protect Socotra. While some have been partly implemented, the Yemeni government argues that conflict and instability on the mainland have obstructed efforts to address them all. In spite of the conflict, development pressures are growing on Socotra and decisions will need to be made over what its future will be. Is the populous north coast already lost, with its new fish packing plant, UAE military facilities and homes for economic migrants and non-Socotri newcomers? Will its interior escape development pressures because it is an unattractive place to live, so too the remote south of the island? Can eco-tourism – unknown on the archipelago until the 1990s – support economic development and encourage environmental protection, once the security situation improves?

It appears inevitable that the intensifying pressures that the islands are facing as they are dragged into the conflict will continue to place their unique natural and social heritage at risk. In common with conservation areas globally, a balance needs to be struck between preserving what is unique and sustainable development. The conflict makes achieving this balance all the more difficult, and in doing so, Socotra risks the same fate as other fragile island ecosystems destroyed by human pressure.

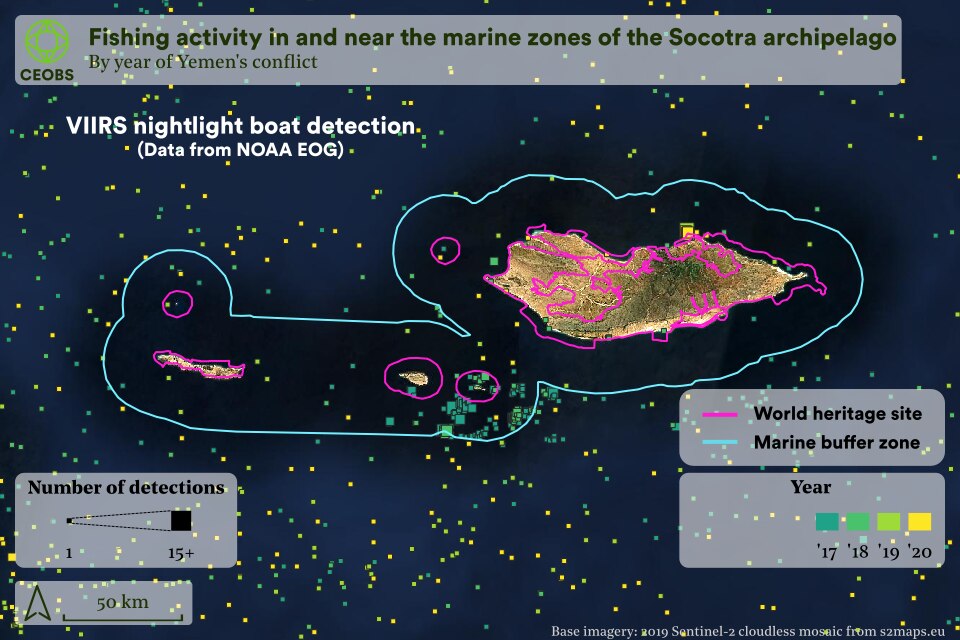

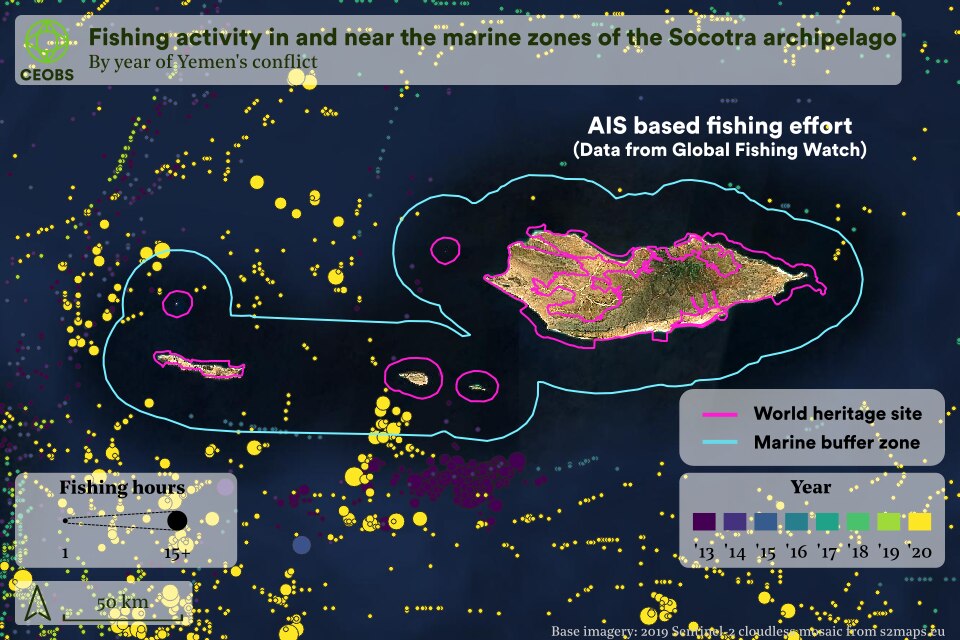

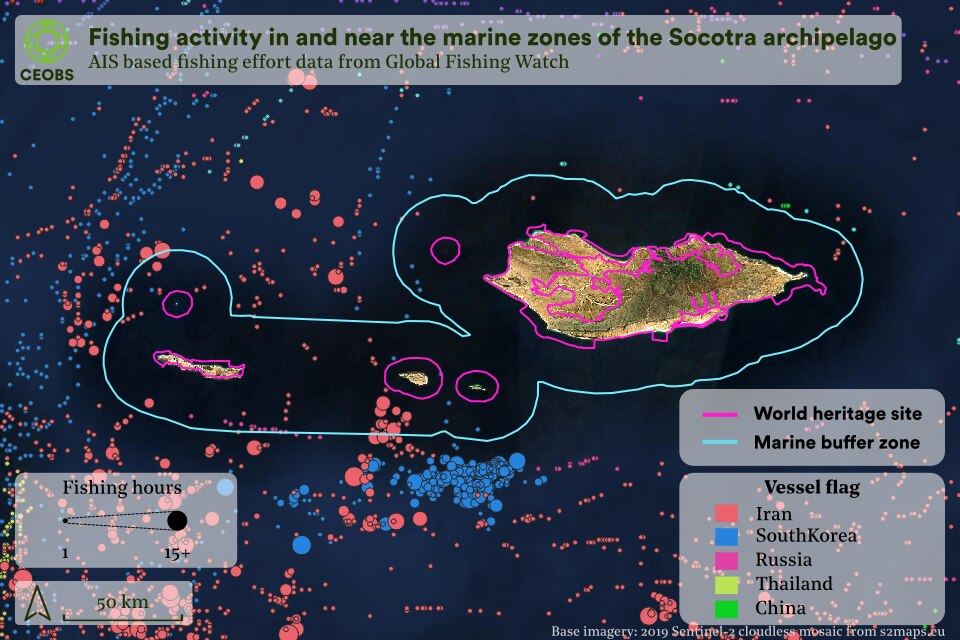

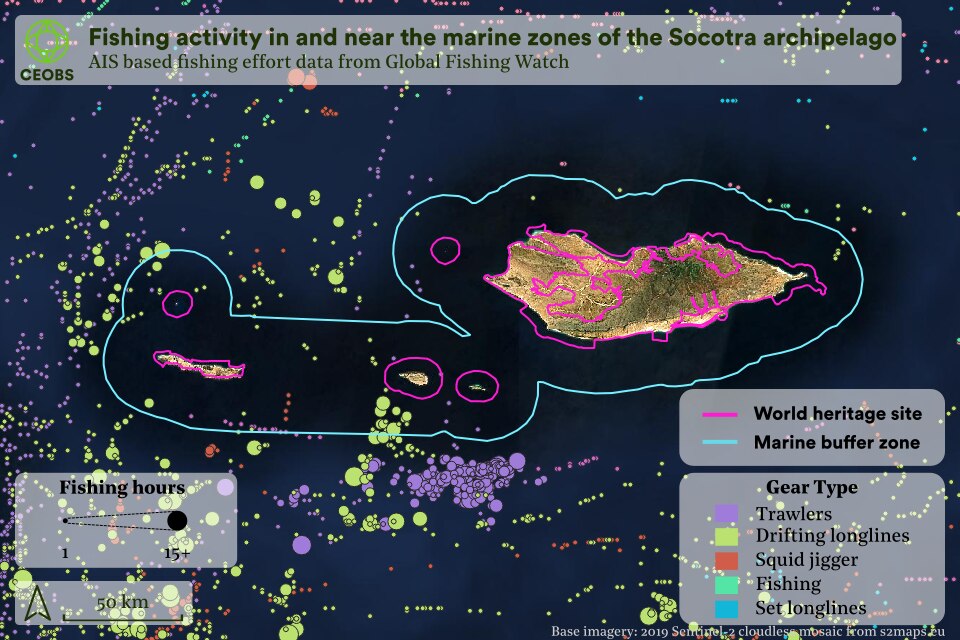

Monitoring illegal fishing in Socotra’s waters

Another means through which Socotra is being harmed by external influence is through the illegal exploitation of its marine resources. There were reports of illegal fishing operations in the north-west Indian Ocean and in the vicinity of Socotra during 2019 and 2020. These analyses were based on vessels’ automatic identification system (AIS). In Figure 8 we use the Global Fishing Watch AIS-based fishing effort dataset to illustrate foreign fishing vessels – in particular from Iran and South Korea – entering the marine buffer zone around the Socotra archipelago. This represents a clear threat to the diverse marine life of Socotra, which includes hundreds of species of coral, fish and crustaceans, and the local livelihoods it supports.

Our analysis of ship transponders and nighttime lights has identified the extent to which foreign-flagged fishing vessels are entering the buffer zone around the islands that is supposed to protect its marine biodiversity.

However, many vessels do not have AIS – it is only a requirement for large boats – or ‘go dark’ and turn it off when operating illegally. As such we have turned to another dataset – boat detections from nighttime lights data, as observed from the VIIRS instrument and processed by the Earth Observation Group at the Payne Institute for Public Policy. This data shows a similar picture of vessels in the buffer zone, but also within the borders of the UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, the spatial pattern is a little different and illustrates the complexity associated with this data – it only represents cloud-free conditions, requires a certain size and brightness of ship to trigger a detection, and not all vessels will be fishing boats. For example, some may be container ships delivering supplies to the capital Hadiboh.

Nonetheless, although information on the composition of the local fleet is limited, from pictures and videos it seems that local boats are mostly small skiffs – for example, as provided by the Saudi Development and Reconstruction Program for Yemen in 2020. These would not trigger nighttime light boat detections, suggesting larger foreign fishing vessels. This is consistent with the data presented by Global Fishing Watch and KSAT, where many vessels identified using satellite radar imagery were not-co-located with an AIS signal – one of these was within the UNESCO boundaries of Socotra.

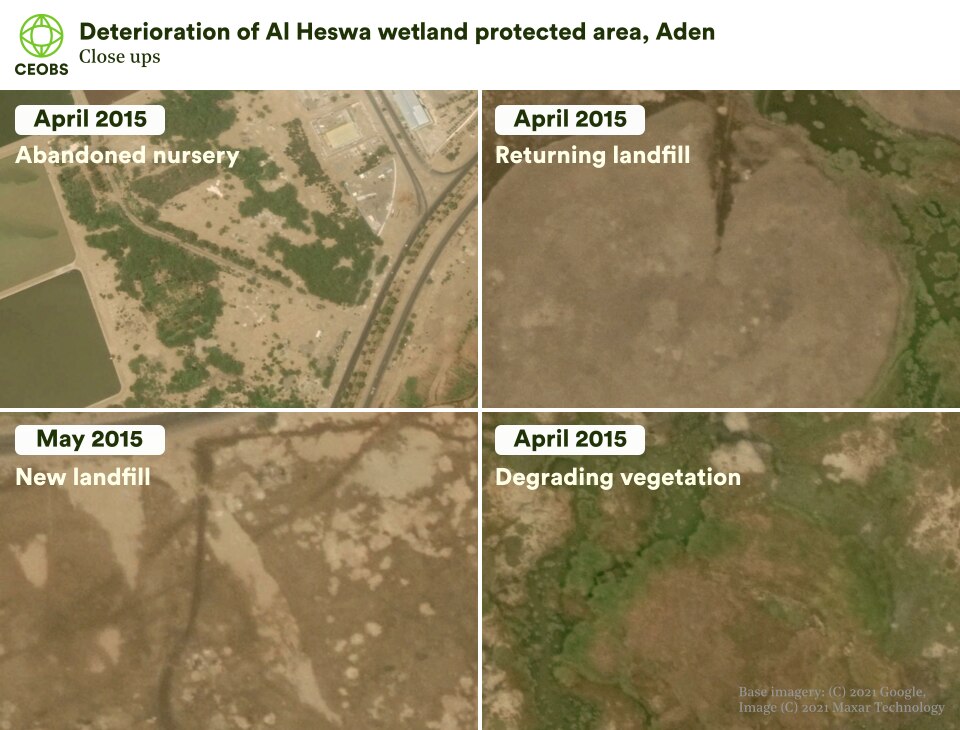

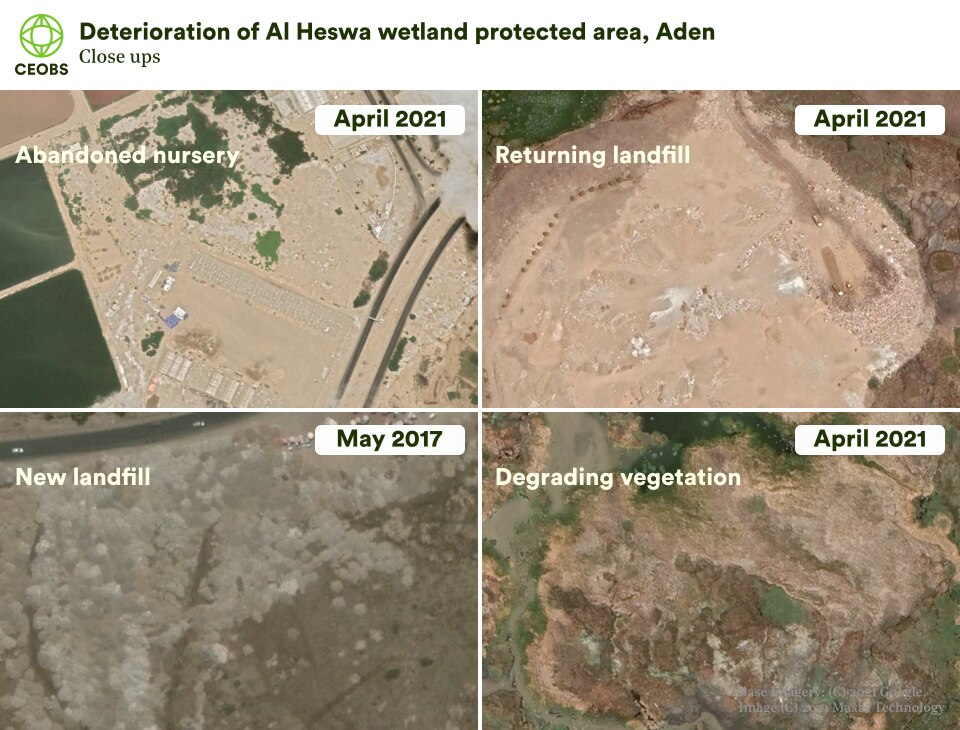

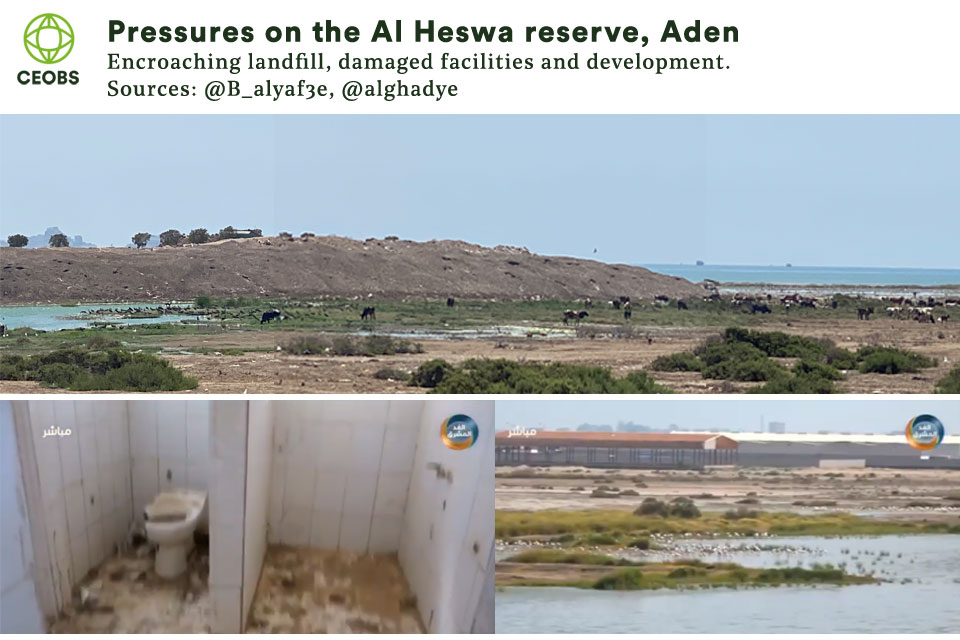

2.4. Al Heswa – the decline of Aden’s urban oasis

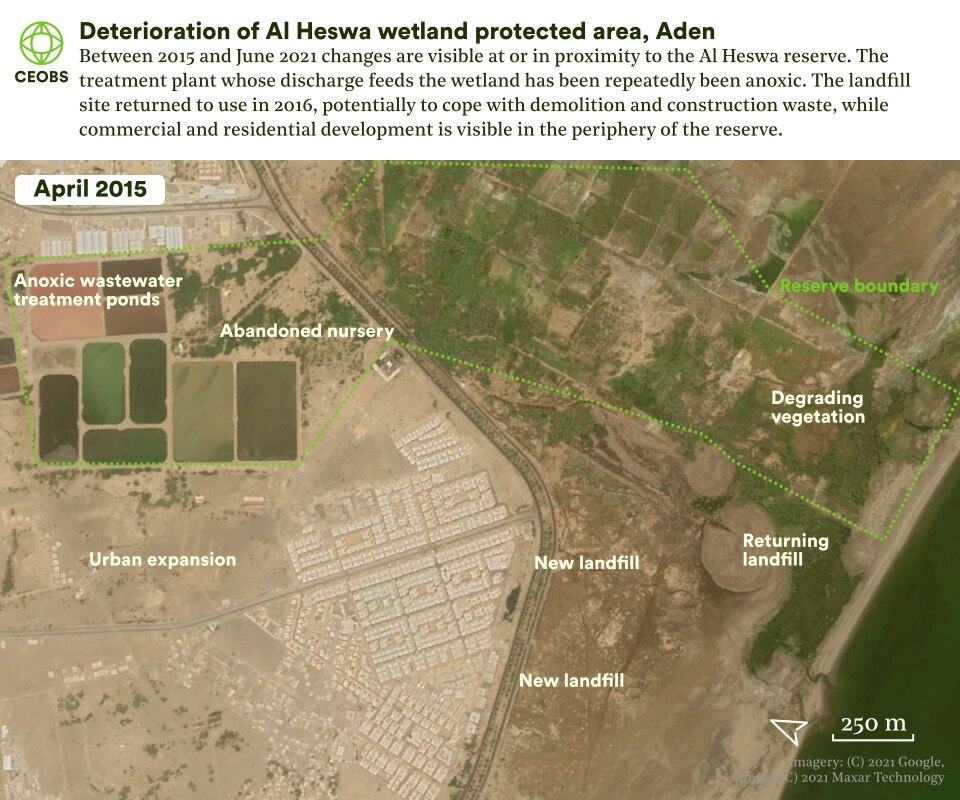

Al Heswa, a component of Aden’s coastal wetlands, is a small – 19 hectare – protected area founded in 2005 with the support of international donors. The natural wetlands are sandwiched between Aden city and the sea and are its only green space. Prior to the establishment of the reserve, they were being degraded by inadequate management practices, and an expanding informal waste dump. Aden’s lagoons and the wetlands are one of the most important sites for migratory birds in the Arabian Peninsula. Developing the reserve was seen as vital for enhancing the feeding and roosting habitats for more than 100 species of birds.

The wetlands are fed in part by the Al-Arish wastewater treatment facility, with small scale farms on the site utilising treated water that would otherwise be lost to the sea. The site has been planned, managed and operated by the local community and NGOs. Revenue was generated from entrance fees for visitors and from crops, and park infrastructure included a two-storey bird viewing platform, car park and paths. In 2012, the park’s revenue reached US$96,000, supporting 250 environmentally friendly livelihoods. The initiative was a first for Yemen and regionally and, in 2014, just before the current conflict escalated, it was awarded the Equator Prize by the UNDP.

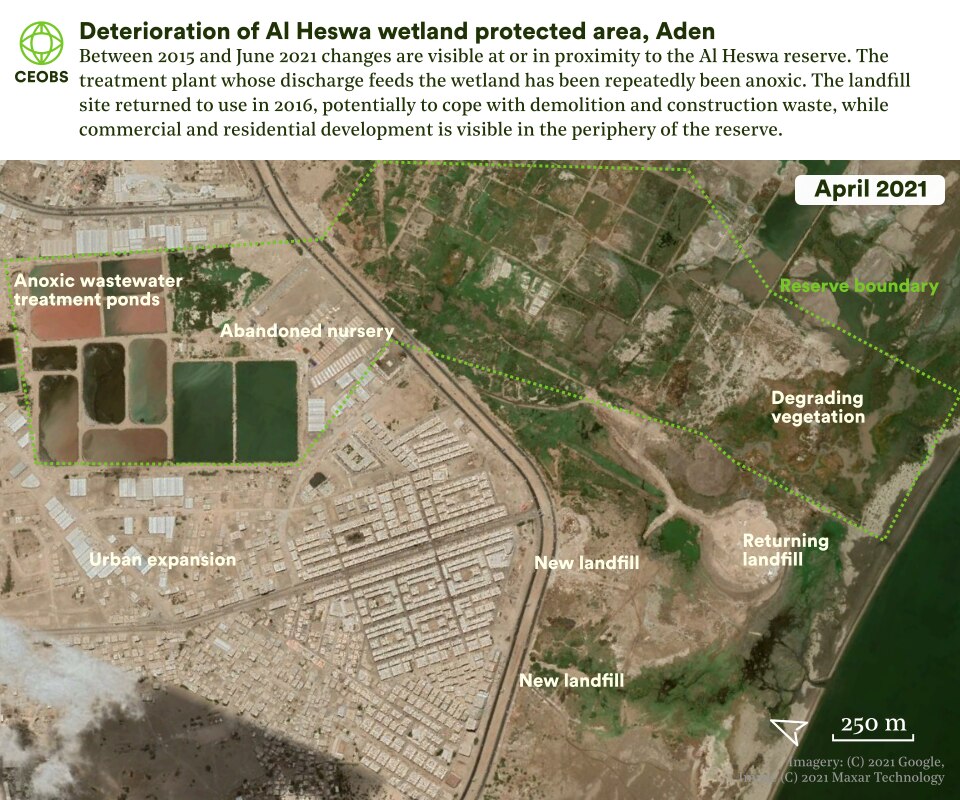

The conflict has reportedly had serious consequences for the project. Financial and political support from the government ceased and, with a drop in visitor levels, its ability to directly generate the revenue that supports its protection and restoration activities has been restricted. Many of its long-term goals have had to be suspended and, while volunteers have continued to maintain the wetland, elements of its infrastructure such as its entry gate and plant nursey have been destroyed.

Satellite imagery reveals that the informal waste dump that the area was developed around has come back into use during the conflict. Fresh deposition is visible from March 2016 onwards, with activity increasing over time. Meanwhile water channels on the site’s western edge have also been infilled with what appears to be building rubble, potentially affecting the hydrology of the wetland. This fits a country-wide pattern in the informal disposal of solid waste. Light industrial units have encroached on the site and on its water source from the treatment plant.

The satellite evidence for pressures that the reserve faces are supported by social media images. A profile of the informal landfill gives some indication of its scale (image composite from post by @B_alyaf3e), while an Aden-based media outlet has reported on the damage to the bird watching hide, and documented the extent of nearby commercial development.

During the conflict we can see recurring periods where settling ponds at the treatment plant malfunction through overloading with organic material, becoming anoxic while turning pink as sulphur-loving bacteria thrive. This is likely to have further reduced the water quality in the marshes. A 2018 damage assessment funded by GIZ suggested that Aden’s Al-Arish plant was largely dysfunctional. In February this year plans were announced to rehabilitate the treatment plant and its basins, and address encroachment on the site by light industrial units. It’s unclear what impact this may have on the wetland.

Calls in the local media to rehabilitate the reserve are growing, and local politicians have been invited to the site to help them understand it’s social and environmental value. Rescuing and restoring the site will require that waste dumping is halted and that funding be found to repair its infrastructure.

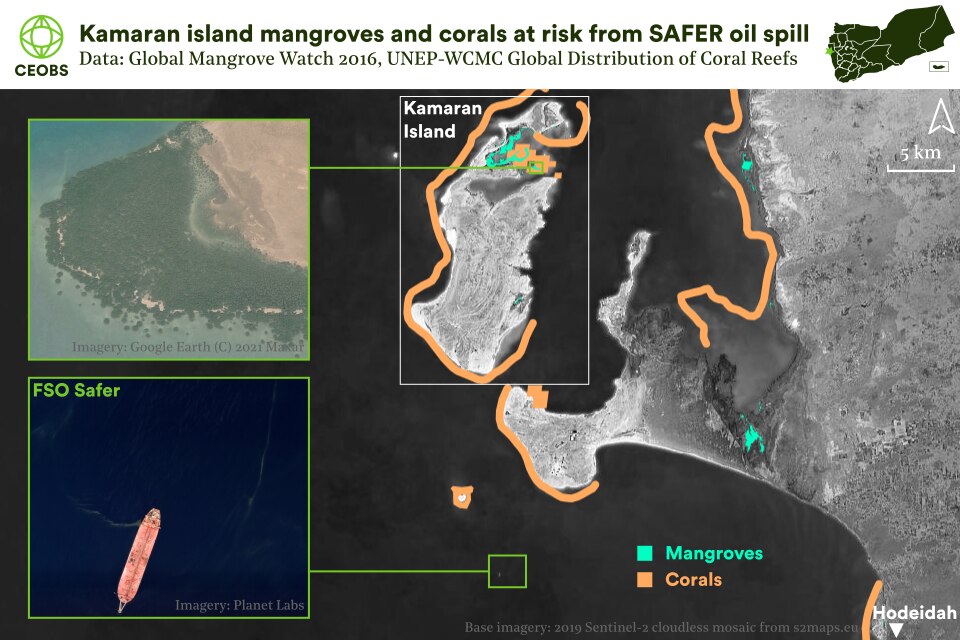

2.5 Kamaran Island – marine protected area threatened by the FSO SAFER

At 57km2, Kamaran Island is the largest of a cluster of small Red Sea islands to the north of the oil terminal of Ras Isa. Low lying and arid, the island is fringed by the richest coral reefs, seagrass and mangroves of Yemen’s Red Sea coast. It is an important feeding area for seabirds and, prior to the last decade, its comparative isolation and lack of development had helped protect its ecosystems. In 2009, the northern part of the island was designated as a protected area by the government, a move promoted by the Regional Organisation for the Conservation of the Environment of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (PERSGA).

Kamaran’s biodiversity value attracted the attention of international donors. In one project, the island and its intact mangroves were to provide a possible model for integrated coastal zone management, which could, it was hoped, provide a template for the mainland. Mangrove stands elsewhere in Yemen have been severely degraded by overgrazing and pollution. Because of the critical importance of mangroves for sustaining inshore fisheries and livelihoods, ecological restoration was viewed as vital for economic development. Protecting mangroves was also a component of nature-based adaptation to climate change, with their ability to store carbon and protect coastlines from storms.

PERSGA also promoted Kamaran as a pilot site for a US$3m project ‘Strategic Ecosystem Management of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden’, funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). Due to begin in 2014, the project sought to ‘improve management of marine resources in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in selected Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) building on resource protection and incentive systems for communities and the harmonization of the knowledge base of marine resources among PERSGA member countries.’

The project would have strengthened the Kamaran MPA by engaging with the local community on its protection. However, as the conflict escalated, Kamaran was dropped in favour of a site in Egypt because of fears over weakening environmental governance. The project review later noted that political instability and violent conflict risked shifting national priorities away from environmental issues and could “disrupt the accrual of regional benefits from improved management of MPAs and living marine resources.”

In the absence of a management plan, a 2013 review by Birdlife identified human intrusion and disturbance as key threats to Kamaran’s biodiversity, with moderate to rapid deterioration likely within four years. How the conflict has influenced the pressures it was facing is unclear but it has also created the threat of an environmental catastrophe. Kamaran lies just 14km north of where the SAFER Floating Storage and Offloading terminal is permanently moored. The SAFER is a converted single hulled, 40-year-old supertanker, which has fallen into disrepair since the Houthis took control of the areas onshore. Repeated warnings have been issued over the risk of an explosion and spill, with the tanker believed to contain 1.14m barrels of crude oil.

Depending on wind and currents, a major spill could potentially devastate Kamaran’s reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds – the ecosystems that underpin its value as an MPA – as well as marine life in the Red Sea more widely. As Red Sea corals have evolved to withstand high temperatures and salinity, their genetic diversity could prove crucial for restoring reefs around the world that have been degraded by climate change. Their protection is therefore of global importance. The threat from the SAFER is so dire that the matter has been addressed by the UN Security Council. Approval for a UN-led technical assessment was finally granted in November 2020. In March 2021 the Houthis were continuing to refuse the necessary security assurances for their UN’s contractors, while in June 2021, talks between the UN and Houthis collapsed. At the time of writing it is still unclear if or when an assessment will take place, and the fate of the SAFER now seems bound to the outcome of the conflict itself.

Kamaran is not the only important area for marine life at risk from spills linked to the conflict. In October 2020, the Syra oil tanker suffered an explosion while taking on oil at the Bir Ali mooring terminal on Yemen’s south coast. As the Syra fled under its own steam, trailing oil, a slick was transported to the environmentally sensitive coastline between Balhaf and Burum. The impact on marine life is unclear, and the case was just one of many examples of spills that were common in peacetime but have grown more serious in the conflict, as vessels have been targeted or suffered damage from sea mines. Poor management of oil infrastructure has also contributed, and is thought to be behind another incident at Bir Ali in June 2021, which saw its pipeline discharge oil into the sea for four days.

3. Prospects for Yemen’s protected areas and wider lessons

The protection afforded to Yemen’s most biologically important sites prior to its conflict was insufficient. This is perhaps unsurprising given its low level of economic development and prolonged political instability. Prior to 2015, the government funded an estimated 20% of identified conservation needs, with international donors and programmes plugging some of the gaps. Weak institutional capacity and under-funding meant that there was, and remains, a gulf between the national laws and decrees on environmental protection and their implementation on the ground.

As the examples above demonstrate, the conflict has influenced protected areas in a number of ways, from cancelled projects, to accelerated degradation and to neglect. In the face of the world’s worst humanitarian crisis, biodiversity protection has inevitably taken a back seat. And yet, for countries like Yemen, where a large proportion of the population are directly reliant on biodiversity and natural resources for their livelihoods, and where these resources underpin their resilience to social and climatic shocks, protecting and restoring biodiversity becomes a humanitarian imperative. This relationship is increasingly being recognised in donor funding for Yemen but as ever, it is a question of whether such projects can be effectively implemented.

More broadly, the pressures facing these sites in Yemen demonstrate that protecting environmentally important areas in conflicts is more complex than current debates on legal designations sometimes imply. For example, none of these sites has been directly damaged through military action. Similarly, on paper at least, Socotra’s UNESCO status should translate into a high level of protection, but it hasn’t. The marine ecosystem of Kamaran, and the wider Red Sea, continue to be held hostage by the Houthis, while the Bura’a and Al-Heswa have been affected by coping strategies, weak governance and neglect. This suggests that we need to pay more attention than we currently do to the indirect drivers of damage to protected areas during conflicts.

The future prospects for the five sites discussed above, and Yemen’s other protected areas, are inextricably linked to the trajectory of its conflict. The longer it goes on, the greater the human pressures and governance disruption will be. And, when it finally arrives, peace will bring with it new threats as development pressure increases. Ensuring that support is in place for governance and management structures, and at both the community and national level, will be key to ensuring that these important ecosystems are protected. Moreover, these structures will be vital if these biodiversity hotspots are to be a tool to proactively support post-conflict recovery and peacebuilding in Yemen.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director. CEOBS’ Researcher Dr Eoghan Darbyshire provided data analysis and visualisations. We are deeply indebted to the conservation experts we spoke to in researching this report.

- A relict (or relic) forest is a remnant of what was once widespread. Relictualism occurs when a widespread habitat or range changes and a small area becomes cut off from the whole.

- Recent research indicates that the role of CO2 fertilisation has been significantly underestimated in past studies, and is the overwhelming driver of greening at the latitudes of Yemen.