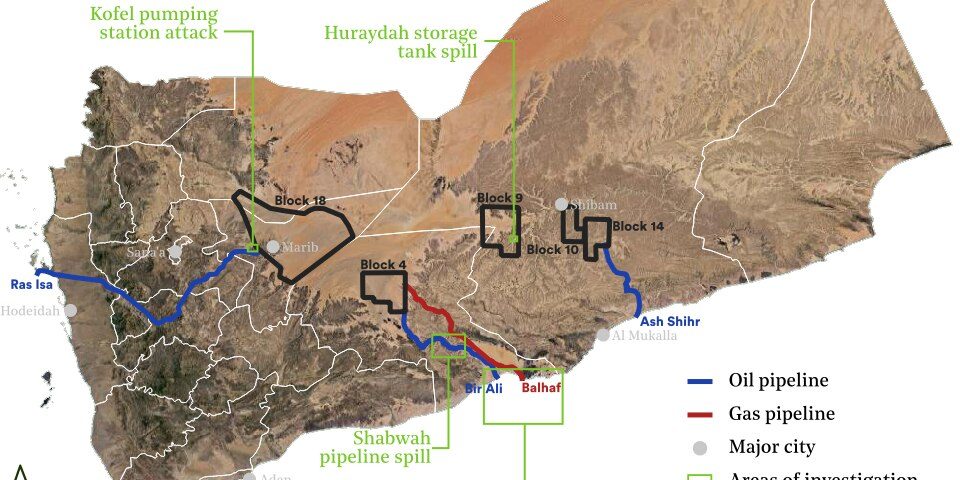

Report on recent oil spills, including two on land, one at sea with potential impacts on biodiversity, and one near-miss on an oil pipeline pumping station.

Whilst attention has rightly been focused on the precarious FSO SAFER oil tanker, which has the potential for a regionally or globally catastrophic marine oil spill, there have recently been a number of reports of smaller scale oil spills in Yemen. From searches of social and traditional media, we have found examples of incidents across the spectrum of oil infrastructure, which to some degree are all linked with the conflict. This includes from well heads, to pipelines, refineries and to transport on land.

Huraydah

Social media and local news agency reports surfaced on the 8th October of an oil spill from storage tanks in the Huraydah area of wadi Hadhramaut. The leak is reported to have started on October 4th, and to have been cleared by the 12th October.

حدبة حريضة تسرب نفط خام👇 pic.twitter.com/ZM2yDY2Uok

— نايف بن قديم (@nife_abdalaziz) October 8, 2020

اطّلعت لجنة برئاسة وكيل محافظة حضرموت المساعد لشؤون مديريات الوادي

والصحراء المهندس هشام محمد السعيدي اليوم على معالجات تسرب النفط من أحد

خزانات شركة كالفالي بقطاع 9 بمديرية حريضة يوم الأحد 4 أكتوبر…للتفاصيل: https://t.co/nnXRH9CWjY pic.twitter.com/C3c5pPnWek

— صحيفة صوت حضرموت(حساب بديل) (@hdrvoice_1) October 12, 2020

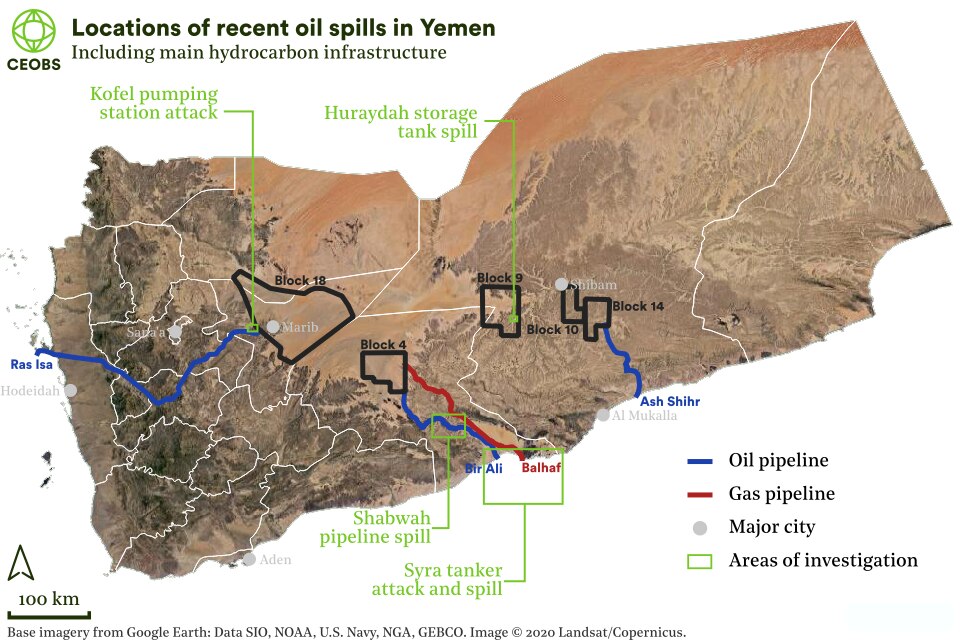

Figure 2. Location of the 4th October oil spill near Huraydah

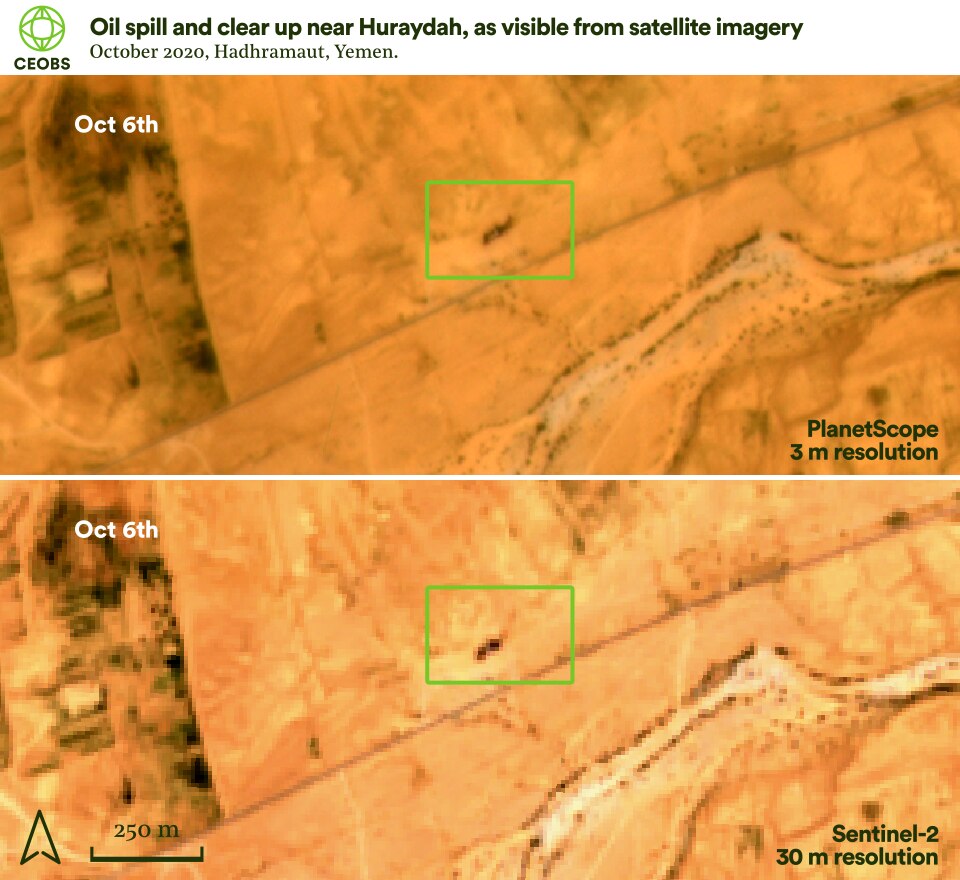

Using high resolution satellite imagery, we have been able to confirm the reports of a spill and locate the area. Although no data is available for the 4th or 5th October, imagery on the 6th from two independent satellites, PlanetScope and Sentinel-2, clearly shows the spill. However, the area covered is relatively small, approximately 2,500m2, and does not reach into nearby farms or the adjacent wadi. It is possible the extent was greater in the preceding two days. The satellite imagery indicates that by the 8th, the spill appears to have been cleared up. The spill may have been pure crude or produced water,1 it is not possible to tell from satellite observations only.

The cause of the spill is difficult to ascertain, especially given that we are relying on translated reporting, although one article mentioned a hole in one of the storage tanks, whilst another stated that they were too full due to the continued diversion of road tankers. Many of the posts on social media blamed Calvalley Petroleum Inc., the Canadian oil and gas company that operates the fields in Block 9 of the Masila oil fields. Although the company ceased operations in 2015 they returned in September 2018, reportedly reconditioning and refurbishing infrastructure.

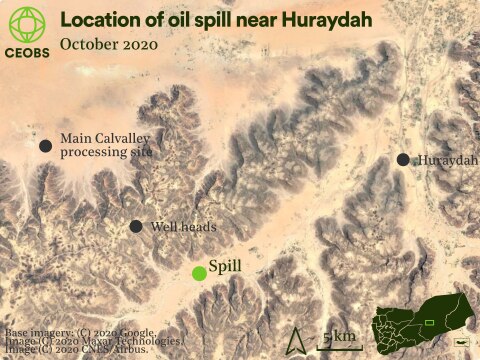

Figure 3. Before and after imagery of the 4th October oil spill near Huraydah from independent observations, Planet Labs Inc PlanetScope (top) and Copernicus Sentinel-2 (bottom).

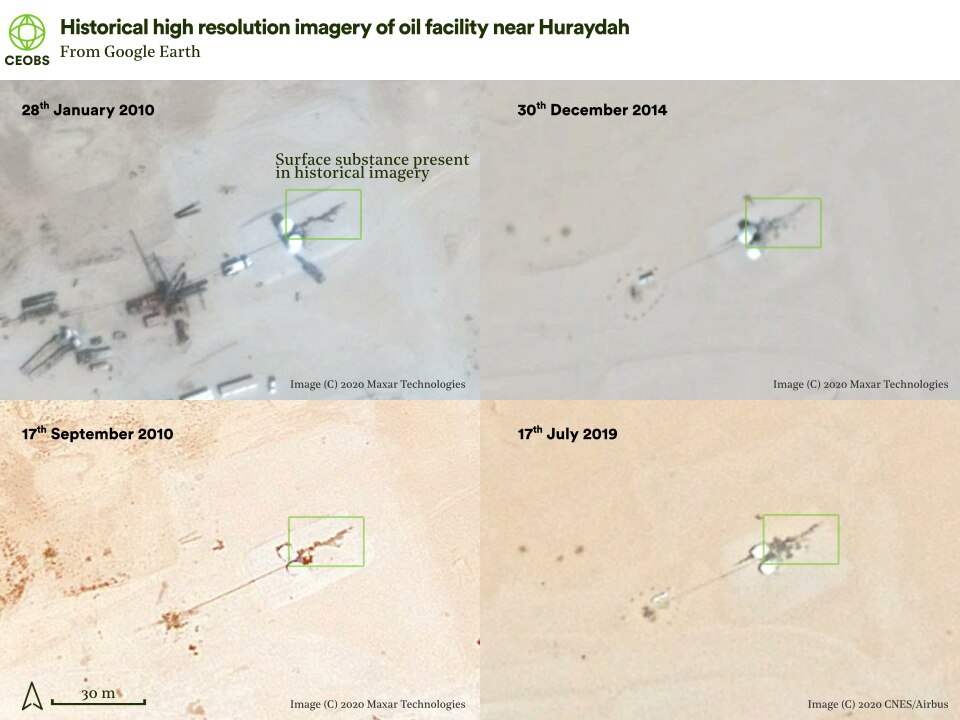

Strikingly, and most unlike in instances other conflict areas, the response here was swift. A committee of officials was formed,2 and engineering work began to replace the contaminated soil. The fate of this soil is unknown. This seems like a good job done, but is this merely superficial? Taking a historical look back with the higher resolution imagery on Google Earth, there has been a substance surrounding the facility since it was constructed – this is assumed to be produced water or oil.

There is also the invisible threat to groundwater from ill-maintained oil infrastructure in the wider region. Groundwater is the main source of irrigation in Hadhramaut. Sometimes this is clearly manifest, such as this unconfirmed report of a farmer digging a water well, but finding the aquifer polluted with oil. Indeed, a 2019 report into the effect of oil wells on human health across Hadhramaut governate concluded that the primary problem was the poorly managed reinjection of produced water back into geological formations, which then migrated to aquifers used for drinking water. Based on survey results, the study noted that rates of cancer, kidney and liver diseases have increased ‘abnormally’ in proximity to areas where these poor practices are used. This report also contained further images of oil spillage and leakage into the environment. Where produced water reinjection has been undertaken without due care elsewhere, it has led to aquifer pollution with toxic materials such as heavy metals.

A further risk arises from the location of some of the produced water ponds on the plateaus above the sunken valleys. In the event of extreme weather there is the risk that these overflow and travel down the wadis onto cropland and into watercourses – there was an example of such an overflow earlier this year in Iraq. Despite these concerns, there are potential opportunities for properly treating and reusing produced water in water scarce regions.

Shabwah

To the south-west in the Shabwah governate, there have reportedly been ongoing spills from the old 200km pipeline connecting the Ayad oil fields to the Bir Ali terminal on the south coast. The first reports are from the 21st February 2020, with additional coverage on social media, and show oil flowing down the dry river bed of Wadi Liyah.

These rivers of oil are only a meter or so wide and thus prevent verification from satellite imagery – currently the best data we have access to has a resolution of three meters. Because the wadis are sunken into the landscape and often in shadow, whilst also covered in shrubby vegetation, any signal from oil is obscured. This indicates one of the big limitations of satellites – they can see big events in space – but not necessarily in time, such as a sustained leak as reported here. Furthermore, if the oil is primarily seeping into the groundwater, such a pollution event is impossible to observe from space.

Nonetheless, a Google reverse image search on these pictures indicates that they only appeared on the date of the posts and thus it is unlikely that the articles are confecting a crisis. Common among the reports was an uncertainty as to the source of the leaks. As such, it was reported that on the 2nd of March 2020 the governor of Shabwah district formed a committee to address the environmental impacts and study remediation solutions. He also called on the Ministry of Oil to ensure that the pipeline was repaired and maintained.

On the 13th April, a tweet emerged of spills 10km downstream, in the Sayyid area of Wadi Liyah and also Wadi Ghayl. Media reports have subsequently helped to flesh the story out, indicating that although the leak was swiftly patched up by the state oil company (YICOM) 3, there was no environmental remediation in spite of the severe effects – the oil had been accumulating in the soil before showing at the surface, and had runoff into groundwater springs, leaving the water undrinkable.

While an inspection was carried out by the Director General of the Environment Public Authority, they lacked basic survey equipment and so only a visual analysis could be conducted. Nonetheless, they concluded that YICOM were negligent, having not met the lowest standards for pipeline maintenance and remediation, and that this incident was only the latest in a string of leaks.

تسرب نفطي هائل يغمر وديان لهية بعد تفجير أنبوب النفط الممتد من العقلة إلى النشيمة #شبوة والذي يعتبر تحت حماية الشرعيه بعد مغادرة النخبه الشبوانية التي كان يسود الامن والاستقرار في شبوه بعهدها

حسبنا الله ونعم الوكيل#النخبه_الشبوانيه pic.twitter.com/qAgDePZq2a

— ابوفهيد (@binshafloot) February 22, 2020

A follow-up investigation in May found that the drinking water was still contaminated and that residents were having to transport water into the area with no help from the authorities. However, this article pointed to another cause of the leaks aside from poor maintenance – bunkering. It was said that opportunists had been creating holes and siphoning off the oil; this would be unsurprising given the fuel crisis that Yemen has been suffering. Furthermore, direct attacks and explosions of the pipeline were reported in October 2019.

The Yemeni environmental platform Holm Akhdar (“Green Dream”) has reported that spills continued until at least September. In an interview, the Director General of the General Authority for Environmental Protection in Shabwa governorate, claimed that the oil companies had been negligent in failing to apply minimum standards, but also raised general neglect of the environment by the state. This manifests as little environmental awareness in government agencies, a lack of interest in enforcing standards, and no consideration of environmental impact assessments for new projects.

The Director General also raised other issues with the pipeline, it was suspected that buried oil waste was responsible for the deaths of many sheep and camels owned by local Bedouin. Despite the agency compiling and submitting reports, he said that they have not been effective in forcing higher authorities to remediate the area. Nonetheless, apparently this interview prompted a visit from the undersecretary of the Ministry of Water and Environment, who promised to raise the issue with the minister.

In the latest development, on the 25th October there was another attack reported on a section of the pipeline near Habban. Apparently this led to a fire, which did not show up on satellite hotspots, and a localised spill, which we were also unable to locate despite a Sentinel-2 overpass on the 26th. This further incident came just two days after oil flow had resumed though the pipeline, following the attack on the Syra (see section below).

Although we cannot see these spills using satellites, the reporting around them appears consistent with a real event. Whatever the cause, be it poor governance, the fuel crisis or bunkering, they are all directly or indirectly linked to the conflict. The real question is the extent of the damage. This is the type of incident that could benefit from locally owned citizen science research, to collect data to quantify the ongoing extent of the damage and push for remediation from those responsible.

Indeed, there are already civil society groups who are working in this space – the Shabwa Foundation for Development and Human Rights held a workshop in October 2019 entitled ‘Environmental oil pollution…the effects, risks, and means of prevention and reduction’, from which one of the main proposals was to establish a monitoring centre to identify and log environmental damage.

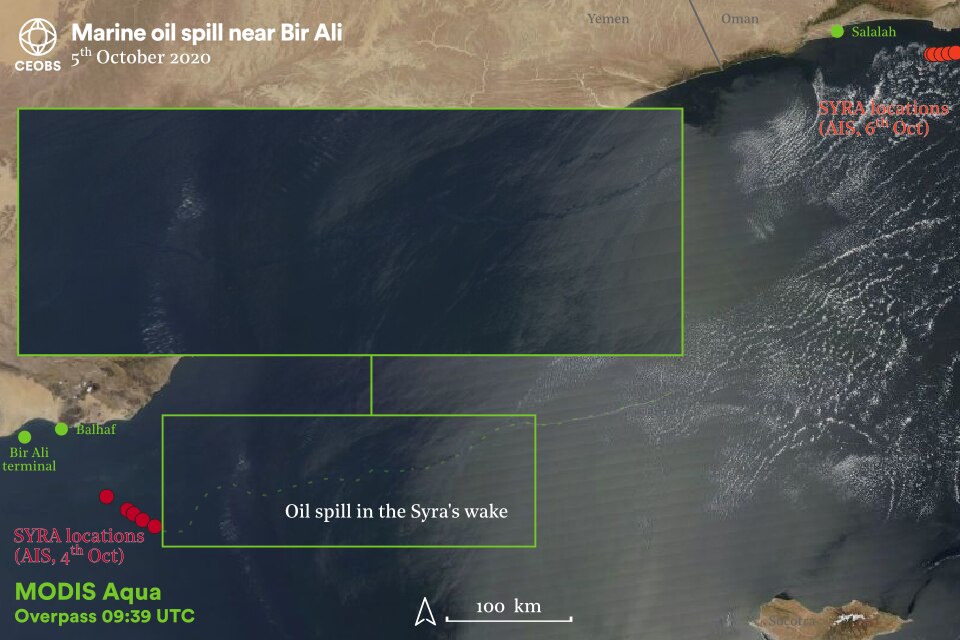

Marine spill near the Bir Ali terminal

From Shabwah, the pipeline travels south and reaches the coast at Al Nushaymah, before heading to the offshore Bir Ali mooring terminal, where tankers load crude oil onboard. As the Syra oil tanker was taking on crude on the 3rd October 2020, it suffered an explosion causing damage to the hull and starting a leak of crude into the Gulf of Aden. The vessel, which was carrying approximately 65,000 tonnes of crude, was able to move on its own power and transited away from Bir Ali towards the port of Fujairah in the UAE.

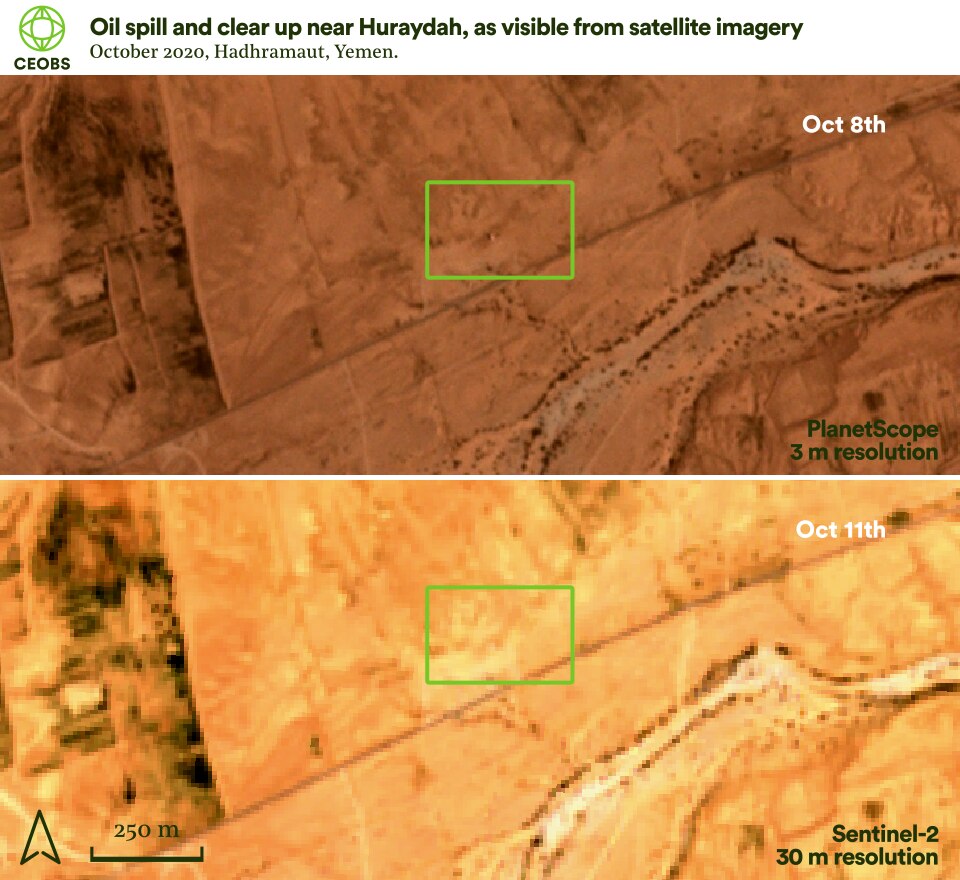

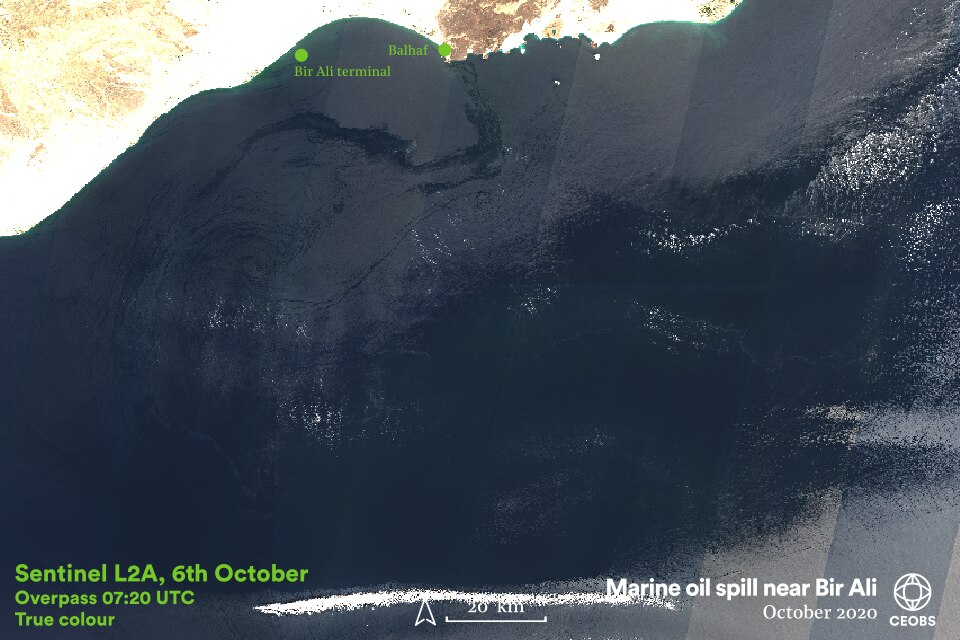

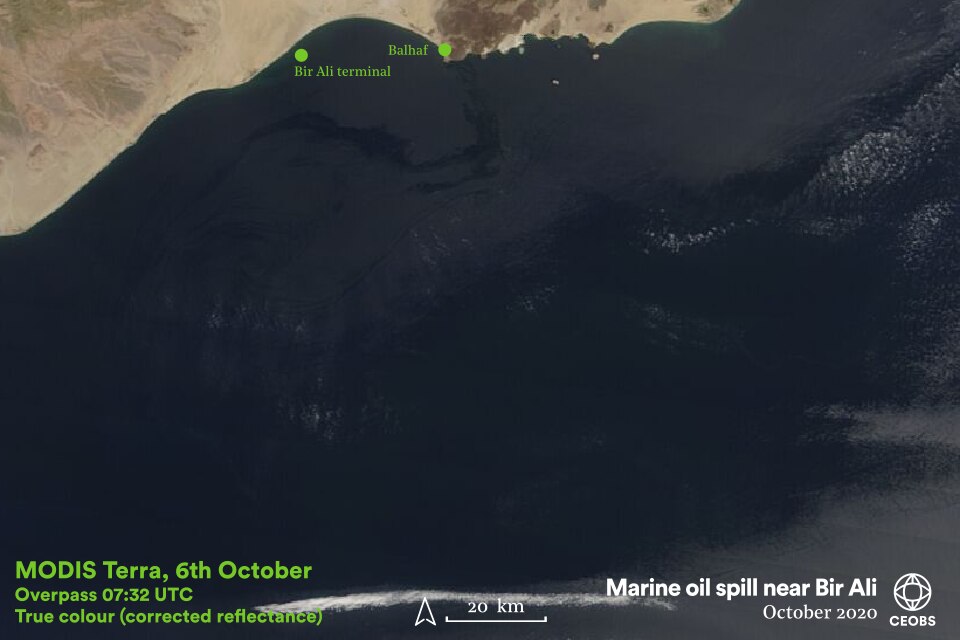

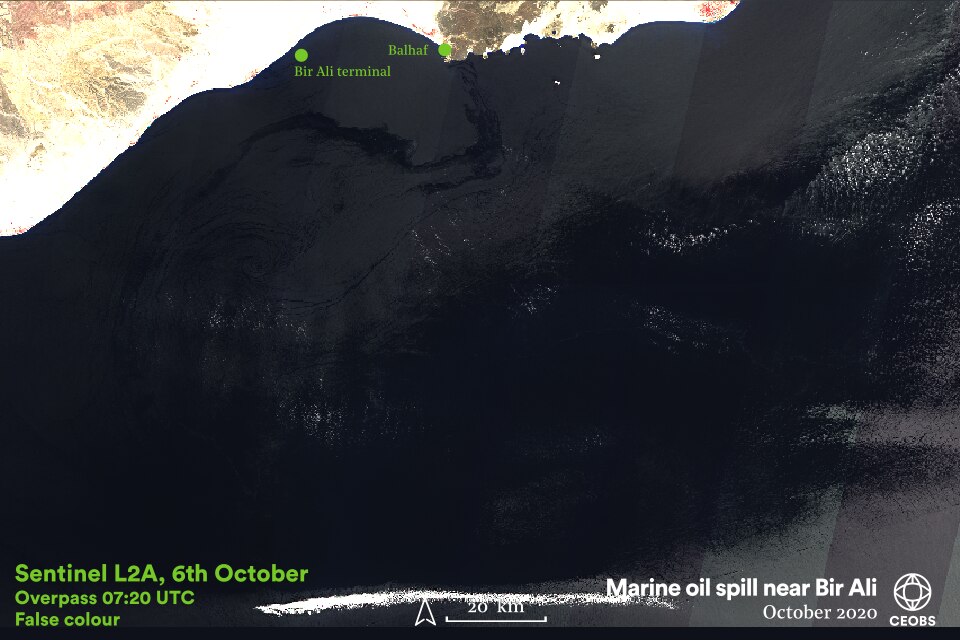

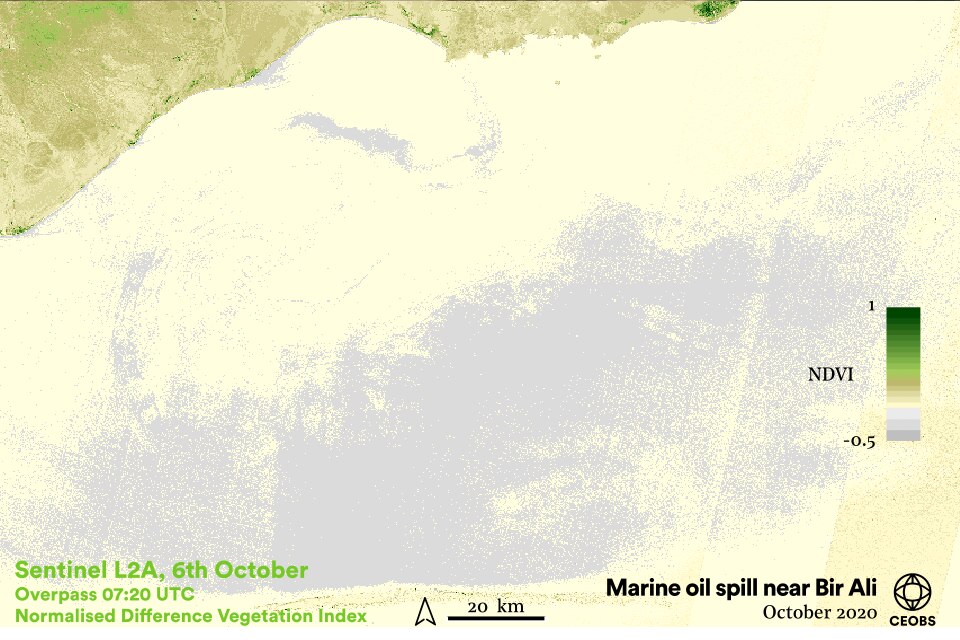

Figure 7. The environmentally sensitive coastline between Balhaf and Burum; key zones are illustrated from the Ministry of Water and Environment’s pilot Coastal Management Zoning Plan. Overlain are Sentinel-2 overpasses on the 6th (top) and 11th October (bottom) following the spill near the Bir Ali oil terminal. Dark areas may be oil – we investigate further below. Credit: Original Sentinel-2 analysis analysis undertaken by Ambrey Intelligence.

Oil was spilt at the mooring terminal and in the wake of the vessel as it sailed away. Satellite imagery from the 6th and 11th October indicates the slick may have floated eastwards towards the environmentally sensitive area between Balhaf and Burum, a reserve that was in line for special protection status prior to the conflict. The area supports a concentrated, diverse and important collection of corals, including species of scleractinia, pocilloporids, faviids and poritids. Large patches of which have developed offshore and fringe the five natural islands along its 125km of coastline. The area is also an important nesting site for seabirds and rare green turtles, whilst supporting dolphins, a diverse and unique fish community, molluscs, arthropods, echinoderms and sea urchins. One striking feature is the seawater fed Kharif Sha’ran lake – sitting within a volcanic crater and surrounded by the only mangroves on the Gulf of Aden coast, it provides a resting site for migratory birds. This coastal strip also help support the local fishery.

Although the darker patches in Fig. 6 appear to be oil reaching the coastline and islands of the reserve, they may just be natural processes such as algal blooms, or the complex mixing of the different water masses in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. In order to establish the likelihood of damage to the reserve, we now chart the spread of the spill from different satellite platforms.

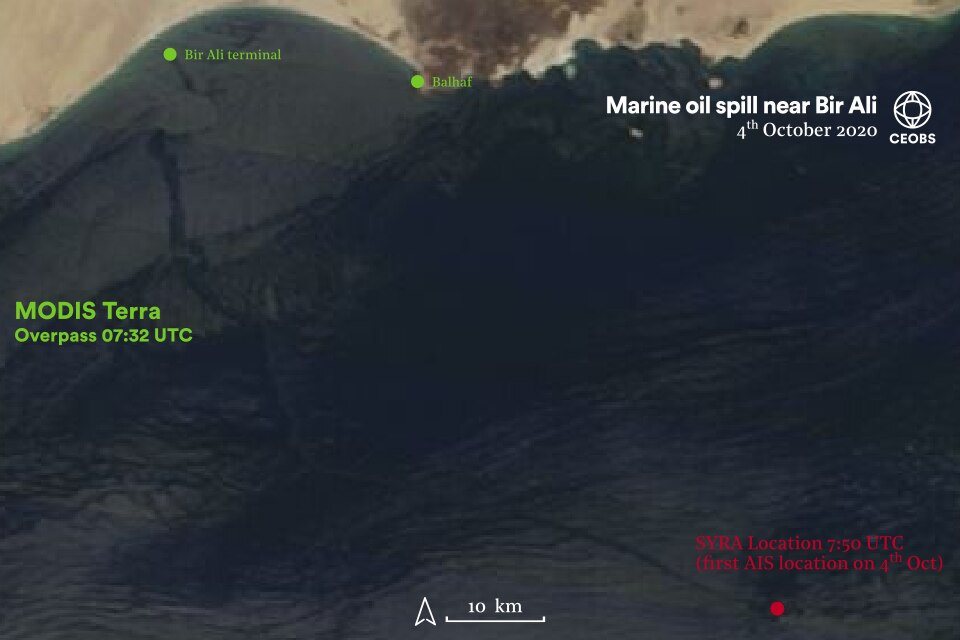

We start with high-resolution PlanetScope imagery from the 4th, which clearly shows the spill emanating from the loading terminal and also spreading in the wake of the Syra as she fled. A wider field but lower resolution view is provided by the MODIS instrument onboard the Terra satellite. The track of the Syra and her spilling oil can be seen clearly, heading south-west towards the international shipping lanes.

Figure 8. Satellite overpasses from the MODIS Terra and PlanetScope instrument on the 4th October, showing the oil spill near Bir Ali. Credit: Orignial PlanetScope analysis undertaken by Wim Zwijnenburg, PAX.

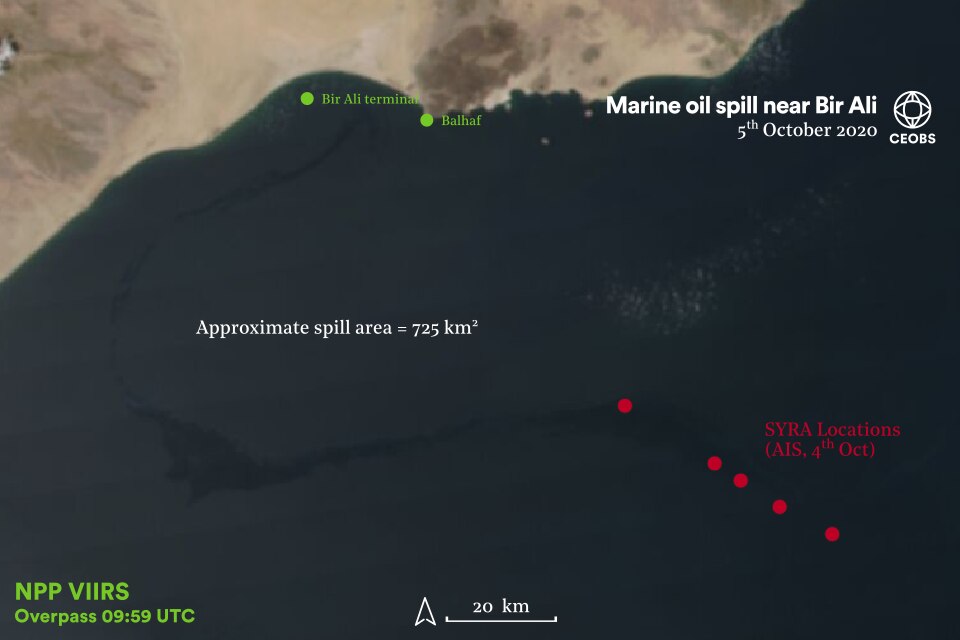

By the 5th October, the Syra is well away from Bir Ali, but the slick still remains visible in the true colour imagery from the VIIRS satellite. The main area of the slick appears approximately 50km offshore. We have conservatively estimated the area of the spill in the vicinity of Bir Ali to be 725km2. There is no information on the depth of the oil slick and thus we cannot convert this to a total volume or barrels equivalent.

The tail of the slick seems not to have travelled much since the previous day, with it still visible directly underneath the known locations of the Syra. This data is from the automatic identification system (AIS) used to monitor global ship movements – we thank FleetMon for providing this information. Unfortunately, there are no AIS data points after 10:22 UTC on the 4th October until 10:25 UTC on the 6th, when the vessel is sitting off the coast in Oman. We assume this is because the transponder was deactivated as a security precaution against further attack.

However, there is a streak visible in the MODIS Aqua satellite data from the 5th October, which we presume is a leak from the Syra. This feature is more than 500km in length, before the trail is lost at approximately 53.8° E (a different Aqua swath with a cloudier scene). This slick is also visible from higher resolution PlanetScope imagery (not shown here), but unfortunately cannot be tracked any further eastwards. The slick location is coincident with the main international shipping channel through the Gulf of Aden, but we assume it is from the Syra as we can track directly back to the spill and her last known position.

There are no signs of a spill in the high-resolution imagery of the Syra off the coast of Oman. It is possible she called at Salalah port in Oman and undertook some repairs, although we have been unable to confirm this, before heading on to Fujairah in the UAE.

By the 6th October the spill remains clearly visible, although it has changed in shape and transited eastwards and toward the ecologically sensitive coastline and islands. In the Terra and Sentinel L2A optical imagery there is also a large dark patch connected to the oil slick’s tail. The question arises, is this oil? Whilst it certainly looks the same, and has a similar spectral signature, it is very unlikely oil. For one thing, closer inspection of the Sentinel L2A imagery shows the tail of the slick in a similar location to the previous days and situated through the middle of the large dark patch. Furthermore, the dark patch is not present on the VIIRS imagery, but the oil spill is.

Most likely this dark patch is a different water mass – as previously mentioned the Gulf of Aden is a particularly complex ocean mixing environment as the saline and warm Red Sea waters meet the cold Indian Ocean. Around the dates of this spill the area near Bir Ali seems to be the interface between the two water masses, with anomalously cold sea surface temperatures. The study of this mixing and the large and small eddies it generates are still an open research question. Also included in Fig. 10 are Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and Sentinel false colour imagery. The lack of moderate NDVI values or red slithers, indicates that there we are not misidentifying oil as algal blooms.

After the 6th October, it is hard to track the spill any further due to the lack of good imagery. There was no Sentinel-2 data until the 11th, the Terra imagery was at a low resolution as the region was at the edge of the swath, and high cloud obscured the scene in the VIIRS images. Clouds were also a problem on the 8th and so the trail of the spill was lost – although dark fragments that could be oil were visible in the VIIRS imagery on the 9th, these could simply be from different water masses. Unfortunately, no Sentinel-1 synthetic aperture radar data were available throughout the period of interest, which offers the best way of remotely sensing oil spills.

Figure 12. Animation of sea surface temperature anomalies 20th September – 10th October (before, during and after the oil spill near Bir Ali). These are indicative of the ocean circulation and mixing in the Gulf of Aden. Data from the Group for High Resolution Sea Surface Temperature via the Nasa Global Imagery Browse Services.

Our analysis leaves an important unanswered question – what are the slithers of dark material between the clear remnants of the spill and the dark patches assumed to be a different water mass? These slithers are visible reaching the islands and coastline of the reserve on the 6th and 11th of October. Over time, oil spills of this size dissipate and evaporate – was the break up fast enough to avoid damage? We welcome further evidence and expertise to help answer this question, in order to ascertain the likelihood that any environmental damage has occurred.

The cause of the initial explosion has not been confirmed, but a number of suspicious objects were reportedly seen floating in proximity to the tanker whilst loading. The assumption is that these were likely floating IEDs or sea mines, which exploded on contact or in proximity to the vessel. No group has yet claimed responsibility, but Ambrey Intelligence suggest the incident was linked to the conflict between the Southern Transitional Council and the Yemeni government.

The risk to oil shipping remains elevated along Yemen’s coast; earlier in the year there was a significant spill from the Sabiti tanker in the Red Sea, and a near miss further east of Bir Ali. Tensions are now even higher in the area around Bir Ali – a day after this incident a tanker was approached by armed skiffs after loading at the Ash Shihr terminal (150km to the east). Indeed, the risk rating for both Bir Ali and Ash Shihr has been raised to ‘elevated’ – it is possible this tactic may be repeated.

Although there was an ‘Emergency Response’ plan in the 2007 management plan for the reserve, it is clear this was not enacted in this case and so unlikely to be in the future, such is the level of breakdown in governance in Yemen during the conflict. The threat to the reserve and the livelihoods that depend on it thus remains. As such continued monitoring is essential.

There may also be a need for further retrospective investigations – we have found reference to a previous spill at Bir Ali terminal, captured by satellite but not known to local specialists, but have not confirmed the date. It may be this incident reported in December 2017, where many fish were killed near the terminal because of a leak from an underwater pipeline. However, this may be a completely separate incident given the management and state of the pipeline.

More investigations and continued surveillance are required

From our initial searches of social and traditional media, we have found many examples of incidents across the spectrum of oil infrastructure. However, it is likely that far more go unreported, and we have only scratched the surface. Furthermore, it is not just oil infrastructure that is of concern; tweets from July purport to show gas leaks at wellheads near Marib. To fully understand the scale of the problem a deeper investigation is required, in particular of the hydrocarbon producing fields during the conflict. All the more so because oil infrastructure has become a military target.

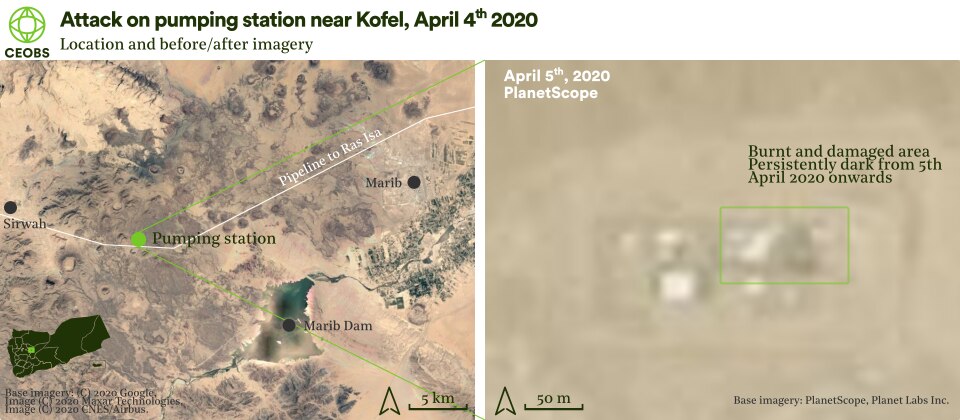

For example, on 4th April 2020, reports started circulating alleging an attack on the Kofel pumping station on the pipeline from Marib to Ras Isa on 4th April. As the station overlooks the Marib Dam, a large-scale spill could have serious ramifications if it entered the reservoir, which supports agricultural irrigation for the Marib area. However, the buildings in the image do not obviously correspond to those at the pumping station closest to Kofel (or Kawfil, Coffel). The incident led to partisan coverage by outlets sympathetic to either the Saudi-led coalition or the Houthis, with no clear consensus of blame, raising the question of whether the attack actually occurred.

From our investigations with high resolution satellite imagery, it seems so. The dark patch, which appears in the north-east corner of the station between the 4th and 5th of April, indicates a fire and damage. Fortunately, there is no oil spill visible, probably because the pipeline is not in full operation. However, it demonstrates that such infrastructure is not off limits and the consequences of the next attack may be more severe.

An added footnote of interest to this investigation is that the image used in the reporting of this attack was used to accompany a different attack on 24th September 2020, in particular by a raft of Iranian outlets. This shows environmental disinformation in action and the value of checking the provenance and distribution of images, for example by using Google reverse image search. But then also showing caution in interpreting these search results – in this case, a technical glitch mistranslated between the Persian and Gregorian calendar and indicated that the first use of the image was in 2016. We were able to confirm this was not the case and indeed we believe the first instance of the image online is on the 4th of April.

Dr Eoghan Darbyshire is a researcher at CEOBS specialising in open source data analysis. Our thanks to FleetMon for providing AIS location data for the Syra oil tanker, and to Holm Akhdar for their feedback and images.

- The wastewater from oil extraction that is reinjected and pumped through the geological formation

- The general directors of the Directorate of Huraida, the Office of Oil, Minerals, Water Resources and Agriculture and the Public Authority for Environmental Protection in Hadhramaut Valley.

- The Yemen Company for Investment in Oil and Mineral