An increasingly unpredictable climate will need to be factored into mine action activities.

Together with Norwegian People’s Aid, we have been considering how climate change may affect humanitarian disarmament. Tajikistan is affected by landmines and cluster munitions and is on the front line of climate change. In this blog, Linsey Cottrell examines what Tajikistan’s experience tells us about the implications of our changing climate for humanitarian disarmament, and how the sector as a whole should adapt.

A shifting environment

While Tajikistan is not one of the world’s countries most heavily impacted by landmines, it is mountainous and the terrain creates challenges for clearance activities. Areas of Tajikistan are contaminated with anti-personnel mines and cluster munitions remnants as a consequence of different conflicts, including its 1992-97 civil war. Parts of its border with Afghanistan were also mined by Russian forces between 1992-98, and the border with Uzbekistan by Uzbek forces between 1999- 2001.

Tajikistan is classed as highly vulnerable to climate change – a combination of the increasing prevalence and intensity of extreme weather events, and its low capacity to adapt to them. Climate change is predicted to bring rising annual temperatures, changes in precipitation and more frequent extreme weather.

Tajikistan’s national mine action strategy for 2017-2020 already notes one of the consequences of this: “As a result of natural disasters, it is possible that some minefields or individual mines have moved to the territory of the Republic of Tajikistan, although, at the moment, their exact location and area are not known”.

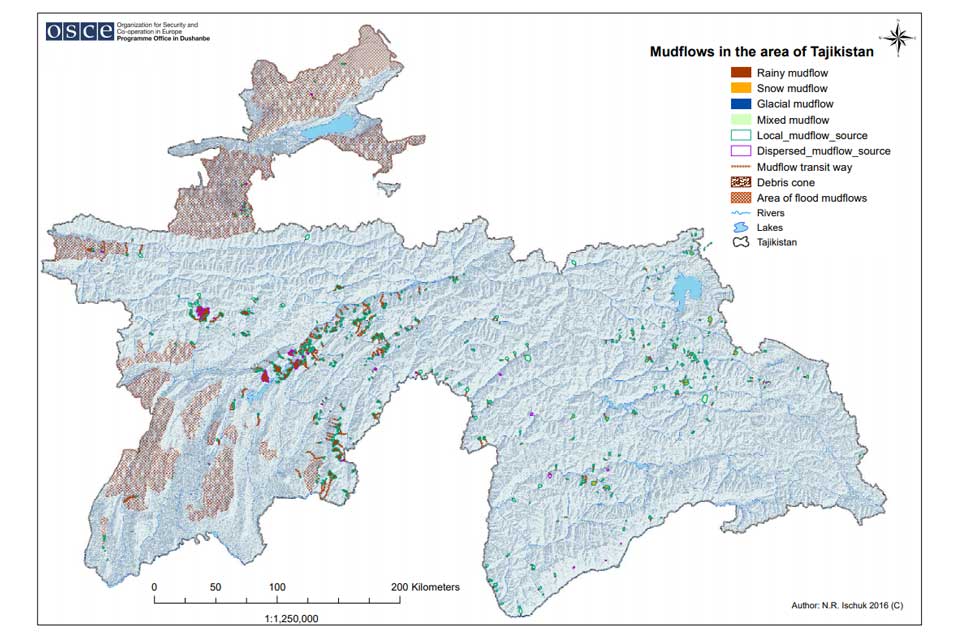

Landslides and mudflows occur frequently in Tajikistan. The majority of mudflows are triggered by extreme rainfall but can also result from increased run-off from melting snowfields and retreating glaciers. The Zeravshan glacier, which is the largest of Tajikistan’s many glaciers, is expected to decrease by 30–35% by 2050. In 2009, more than 40 districts suffered from the impacts of heavy rain, flooding and mudslides. In 2017, a torrent of water sent tonnes of mud and rock debris through the Rasht valley in the north of the country. While in April and June 2019, torrential rain again caused severe mudslides, including events in Ayni and Roudaki districts which border Uzbekistan.

Landslides and mudflows in Tajikistan are often considered non-hazardous since they occur in remote areas, away from infrastructure or populated areas. However, if they occur in areas confirmed or suspected as being contaminated with landmines, there is the potential for them to be carried ‘downstream’ and present risks to previously unsuspecting communities. It also means that records on the locations of minefields become unreliable and new assessments are required. Increased periods of rainfall can also delay mine clearance activities and affect the choice of clearance techniques used.

Climate-vulnerable areas

The government has already identified the need to prioritise climate change adaptation and develop practical measures to prevent and reduce the impact from natural disasters. Mudflow mapping and analysis by Tajikistan’s State Observations Service of the Main Geological Survey has highlighted the river valleys most at risk from floods and mudslides.

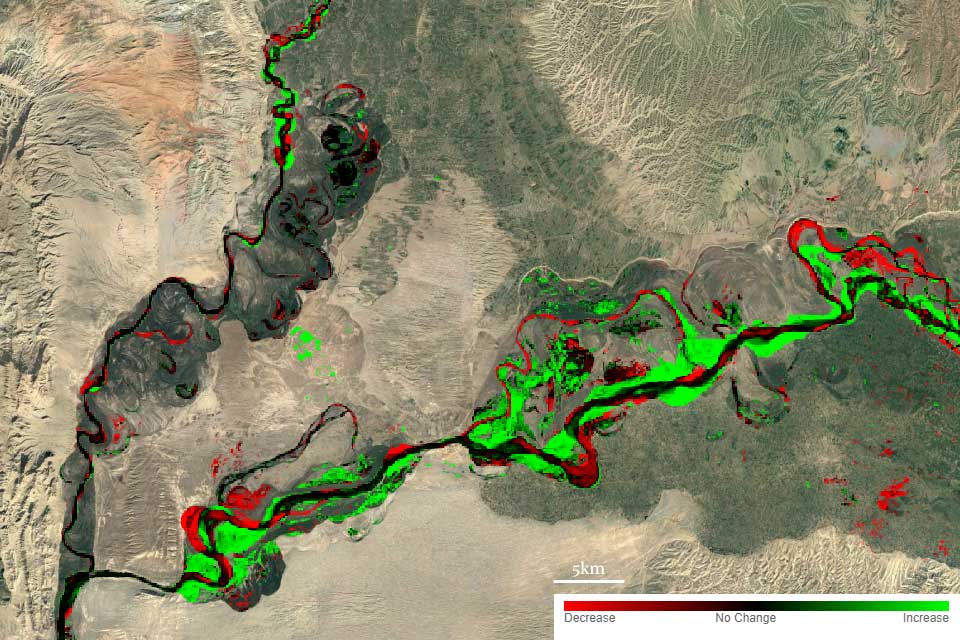

Other climate-vulnerable minefields include two islands in the Panj river on the Tajik-Afghan border, which are at risk from erosion. Satellite maps of changes in surface water intensity for the Panj River area indicates how dynamic and variable the river system can be. Increased river flows from extreme rainfall events or glacial runoff will accelerate erosion.

Planning for the future

The identification of climate-vulnerable areas is beyond the role or expertise of either mine clearance operators or national mine action authorities. In theory, the forthcoming World Meteorological Organisation and World Bank Flashflood Guidance System should assist in predicting the short-term risks from flash floods. In the future, climate change adaptation planning for countries in Central Asia, including Tajikistan, will be supported by the World Bank’s Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Program for the Aral Sea Basin project. This is expected to develop detailed modelling and climate change information.

Climate change risks need to be considered alongside national mine clearance strategies, with clearance programmes or techniques adapted accordingly. In Tajikistan’s case, while overall contamination levels are relatively low, its confirmed or suspected mined areas are concentrated along its national borders. This creates the complexity of mines being displaced from one country to another, such as along the Uzbek-Tajik border due to landslides or flooding. This could cause cross-border issues and tension.

Tajikistan is not unique in its vulnerability to climate change, and understanding climatic risks and incorporating adaptation plans into national mine clearance strategies will be required for countries around the world. Angola, for example, remains heavily contaminated by anti-personnel mines, in spite of years of mine clearance activities. The full impact of climate change on minefields across Angola is not currently known, although the Red Cross has reported that landmines have been redeposited by floods in the south of the country. Its Cuando Cubango province remains heavily contaminated and is at high risk from more variable and intense periods of heavy rainfall. With major rivers flowing through the province into the Okavango delta, there is also the potential for transboundary issues with neighbouring Namibia.

Embedding climate adaptation across the sector

What would climate adaptation planning look like in practice? Country-level adaptation planning by governments should incorporate co-ordination with national mine action authorities to review whether confirmed or suspected minefields lie in climate vulnerable areas. Some areas previously considered as low priority for survey and clearance may need to be re-prioritised if they are assessed as being vulnerable to the local effects of climate change. These might include areas close to river banks, floodplains or steep slopes. If left untouched, there is a risk that such areas may become more technically challenging and costly to clear. Other considerations might include the impact of unpredictable weather on field access, and how best to integrate environmental data into information management systems.

However, little guidance is currently in place to support mine clearance operators in assessing or managing the ways in which climate change can affect their work. And in many countries, detailed climate modelling data may be absent or incomplete. One initial task could be the development of an International Mine Action Standards technical note on how to evaluate or plan for the impacts of climate change. Ensuring that climate change features alongside wider environmental considerations in the implementation of humanitarian disarmament treaties – such as the upcoming Lausanne Action Plan for the Convention on Cluster Munitions – would also help encourage policy development. The donor community also has a role to play by requiring that these issues are addressed in reporting.

Linsey Cottrell is CEOBS’ Environmental Policy Officer. Thanks to Viktor Novikov at Zoï Environment Network for additional background material on Tajikistan.