As world leaders and civil society convene in Dubai, what will COP28 hold for issues at the intersection of militarism, conflict and the climate?

Ahead of arriving in Dubai for COP28, Ellie Kinney outlines the key topics and trends at the intersection between climate change, conflicts and peace. As global military emissions rise, and with new and protracted conflicts capturing international attention, how is this impacting climate diplomacy?

A controversial choice?

The UAE has, understandably, come under a lot of criticism since it was announced that the petrostate would hold the COP28 presidency. From giving the top position in the annual climate negotiations to its national oil company’s CEO – Sultan al-Jaber, to doubling the number of attendees compared to COP27 to a whopping 70,000, or the revelation that the UAE planned to use its role to strike oil and gas deals, there’s reason to approach the conference with scepticism.

COP28 will be fighting for headline space alongside multiple tragic conflicts happening across the world. With increasing focus on how their climate and the environmental impacts are exacerbating human suffering, alongside a presidency supposedly putting ‘peace’ on the table for the first time with a thematic day, what can we expect from COP28 at the intersection between conflicts, militarism and the climate crisis?

Peace one day?

In June, the UAE announced that COP28 would host a special themed day on ‘Relief, Recovery, and Peace’ for the first time. The decision was met with enthusiasm by civil society, who recognise the relationship between peace and the climate crisis. The first offering of the presidency’s focus on this topic arrived in the form of the Declaration on Climate, Relief, Recovery and Peace, due to be published during COP28. The declaration acknowledges the need for ‘bolder collective action to build climate resilience’ while focusing on countries and communities affected by fragility or conflicts. It stresses that financial resources, capacity, partnerships, data and information access must be scaled-up urgently in these areas, and recognises that support must be tailored to the specific needs of people in conflict-affected settings.

This is undoubtedly a welcome step forward, in particular for its highlighting the need for climate finance to be conflict-sensitive. However, the declaration fails to acknowledge the bidirectional relationship between conflicts and the climate crisis. The climate crisis is exacerbating fragility and conflicts across the world but wars are currently emitting the equivalent of whole countries, with alarming consequences for global climate action. Nor does the declaration request endorsing governments to reduce the environmental impacts of their military activities – which can exacerbate vulnerability, or even to pursue peace.

This approach is reflected across the event programme for the 3rd December’s peace-themed day, with its focus on traditional climate security framings around how the climate crisis is exacerbating conflicts. Nevertheless, attention on the need for conflict-sensitive climate finance, and the role of the humanitarian sector, are welcome. These are undoubtedly issues worthy of focus within COP, but with no attention on how war or military activities are impacting the climate, and with no requests for governments to even report, never mind mitigate, their military and conflict emissions, is the UAE merely peacewashing?

The military emissions gap

No country is obliged to report the emissions from its military activities, thanks to an historic exemption lobbied for by the US. Since reporting is voluntary, data reported to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is at best, patchy and at worse, entirely absent. Each year, we update our Military Emissions Gap website ahead of COP with the latest data from the UNFCCC, alongside our analysis of the accessibility of that data in national reports, and a rating of the scale of the gap in national emissions reporting. This has now been updated with the data submitted to the UNFCCC this year, which covers emissions generated during 2021.

Our analysis finds that no country has improved its reporting, in fact Norway’s has actually got worse. Norway has moved from reporting both its stationary and mobile military fuel use data in 2022, to providing only mobile data this year – although it’s worth noting that Norway’s mobile fuel use was recorded as falling. As with last year, the countries that do report tend to provide only mobile military fuel use data, which we know is nowhere near the full scale of military emissions, and out of these countries, Canada, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, United Kingdom and the United States all reported an increase in military emissions.

Interestingly, Ireland, Japan and New Zealand all failed to report any of their military emissions to the UNFCCC but do report some of their military emissions in their own defence ministry reporting. This suggests that these countries are fully capable of measuring and publicly reporting some of their military emissions, but the UNFCCC reporting exemption allows states to get away with not disclosing them in global reporting. In sum, this year’s data provides a frustrating outlook on the state of military emissions reporting, and underlines the need for standardised, robust and transparent reporting across states. By next year, we should be able to see whether the public and media attention on this issue since 2021 has impacted reporting.

Conflict emissions

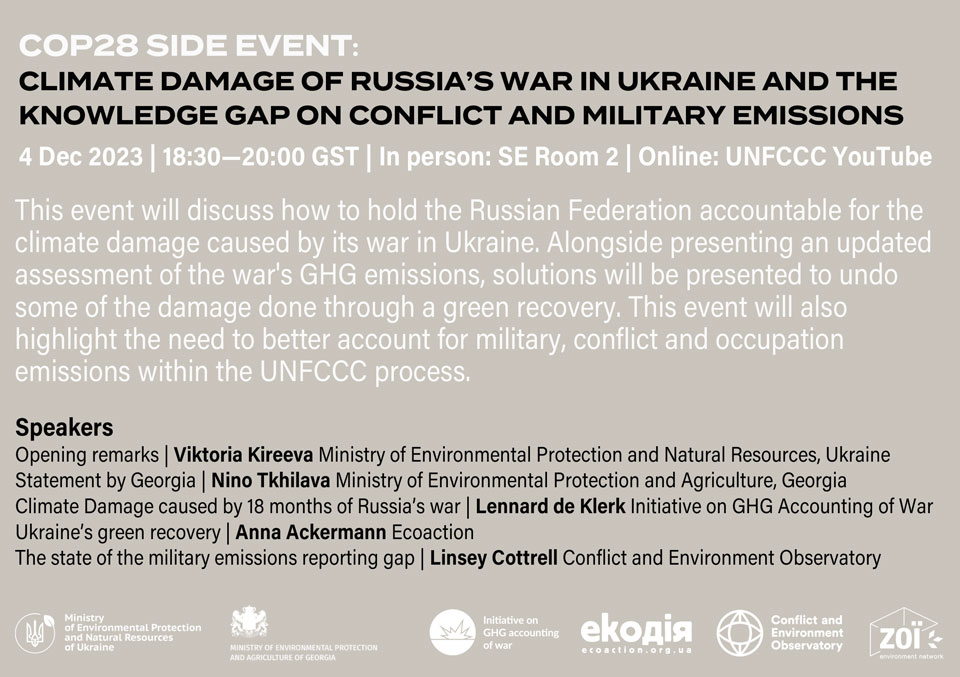

While not on the formal agenda, it is becoming increasingly difficult for the UNFCCC to ignore the emissions caused by conflicts. At present, these are not specifically accounted for in any reporting, nor is there an internationally agreed methodology for their measurement. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a group of researchers has set about developing their own estimate of the war’s impact on the climate, and their latest report reflecting on 18 months of the invasion will be launched at our jointly organised side event.

Their last report estimated that the first year of the invasion produced emissions comparable to a country the size of Belgium over the same time period. This dramatic statistic highlights the scale of this reporting gap, as well as the likely impact on global efforts to reduce emissions. During Israel’s recent bombardment of Gaza, many have questioned the climatic impact of the destruction but with no internationally agreed framework for calculating it, no accurate figure is available. For now, every conflict highlights this huge gap in global emissions accounting, amid the tragic devastation and loss of life. While we’re unlikely to see progress on how the UNFCCC deals with conflict emissions at COP28, this issue is rising in importance.

Emissions from occupied territories

The joint side event will also consider accounting for the emissions resulting from situations of occupation and disputed sovereignty. So far, no consensus has been reached on how to address this, meaning that different states approach their reporting differently – resulting in inaccurate reporting.

For example, Russia began reporting annexed Crimea’s emissions from 2016, resulting in double counting within the UNFCCC data. However, China chooses not to report Taiwan’s emissions despite claiming sovereignty of the island. Since Taiwan is not a recognised state within the UN and cannot report its own emissions, they go unreported. Where one dispute over sovereignty leads to double counting, another leads to a huge gap in reporting, and these are just two of the numerous politically charged examples of where conflicts over disputed land impacts global emissions accounting. Since UNFCCC data runs two years behind, next year will see Russia decide whether or not to increase the area of occupied Ukraine that it chooses to report on, potentially catapulting this issue into the spotlight.

Global Stocktake fails to take stock?

The first ever Global Stocktake culminates at COP28, a process that seeks to enable countries and relevant stakeholders to review progress towards the Paris Agreement’s goals. Crucially, it aims to identify gaps in climate action and suggest solutions and pathways towards progress. According to the UNFCCC, it is ‘a moment to take a long, hard look at the state of our planet and chart a better course for the future’.

Many would argue that this is urgently needed since recent predictions put the world on track for a 2.5-2.9°C temperature rise, rather than the Paris target of 1.5°C. However, a thorough Global Stocktake should consider the military emissions gap, and recommend that militaries set reductions targets in line with the Paris Agreement. But so far, no outputs of the Global Stocktake have even acknowledged the military emissions gap, despite civil society highlighting this in both an open submission and participation in a technical dialogue earlier this year. This is a key moment to highlight gaps in climate action and steer us towards a liveable future for all. A failure to recognise the military emissions gap is therefore a failure in global climate action.

An increasingly intersectional climate movement

The tragic conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan Yemen and many more areas around the world make the outlook seem bleak. But a cause for optimism at COP28 is the climate movement’s solidarity with victims of war, which has triggered growing awareness of the relationship between conflicts and the climate crisis. The Women and Gender Constituency, which represents women’s rights and voices in the UNFCCC process, recently formed a Peace and Disarmament Working Group with the support of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. The group is hosting one of many events at this year’s COP on the intersection between climate change and militarisation.

YOUNGO, the group representing global youth in the UNFCCC process, has similarly set up a Climate, Peace, and Security Working Group and been successful in lobbying the UAE to develop a Youth, Peace and Security Framework, which will be launched in 2024 in collaboration with YOUNGO, UNICEF, and UNFPA. The Climate Action Network, a global network of more than 1,900 civil society organisations in more than 130 countries, addresses the scale of military emissions in its COP28 Policy Document, and calls for leaders to reduce and re-allocate military spending towards climate finance to reduce emissions and scale up climate action.

Even UNEP’s flagship Emissions Gap Report has acknowledged the problem of underreported military emissions for the first time this year. There are also a record number of side events and events in pavilions focusing on climate, conflict and peace, and a growing coalition of civil society organisations that agree that the ‘successful implementation of the Paris Agreement will only be possible with a conflict sensitive and peace responsive approach’. While policymakers may be frustratingly slow to act on military and conflict emissions, the climate movement is definitely picking up pace and may yet bring the UNFCCC with it.

Conflicts hang over COP29

Reflecting on this, there’s no denying that the wars around the world are impacting the UNFCCC process. This is most glaringly obvious in the fact that no host for COP29 has been agreed yet. The conference is due to take place in Eastern Europe but Russia continues to block any EU country from taking the reins, leaving a huge question mark over who will coordinate a year’s worth of urgent global climate action. The effects of conflicts are rippling, and in some cases crashing, through climate diplomacy and accounting, and governments must be prepared to address this.

Ellie Kinney is CEOBS’ Campaigner