Researchers are already using citizen science in fragile and conflict-affected settings.

At this year’s European Citizen Science Association conference, we were privileged to host a workshop on how citizen science can be used in conflict zones. We were joined by experts from the University of Bath, the Palestine Museum of Natural History and ECOSOC, a social enterprise based in Somalia. This report by Linsey Cottrell summarises the workshop presentations, follow-on discussions and plans for the way forward.

The promise of civilian science

We have been exploring how citizen science could be used to assess environmental harm in areas affected by armed conflict. Our European Citizen Science Association (ESCA) workshop aimed to present ideas, learn from case studies and discuss the challenges of using citizen science in fragile areas where there are multidimensional threats to the environment. These threats may be caused by direct military attacks, for example leading to industrial damage and pollution, the loss of urban infrastructure or the destruction of natural habitats, or they might be due to the exploitation of resources or the collapse of environmental governance. COVID-19 meant that the conference was moved online, but the revised workshop format still allowed for insightful discussions over how citizen science can be deployed in challenging and conflict-affected contexts.

Studying environmental harm in conflict zones remains a huge challenge and is typically restricted by access, security and capacity constraints. Assessments can be made using remote sensing and satellite images, but these provide only part of the story and often require on-the-ground validation – data from citizen science can help reveal the full picture. Data on harm is needed to target environmental assessments, to understand the extent of damage caused and to ensure that the right assistance is provided, in order to address harm to people and ecosystems.

We believe that citizen science could be a valuable tool to plug the gaps in environmental monitoring associated with conflicts, and in turn has the potential to empower affected communities, increase the visibility of environmental issues and help to increase accountability for harm.

Lessons from current citizen science

Citizen science is already being used in fragile and insecure contexts, and our workshop heard from three practitioners with experience in these settings.

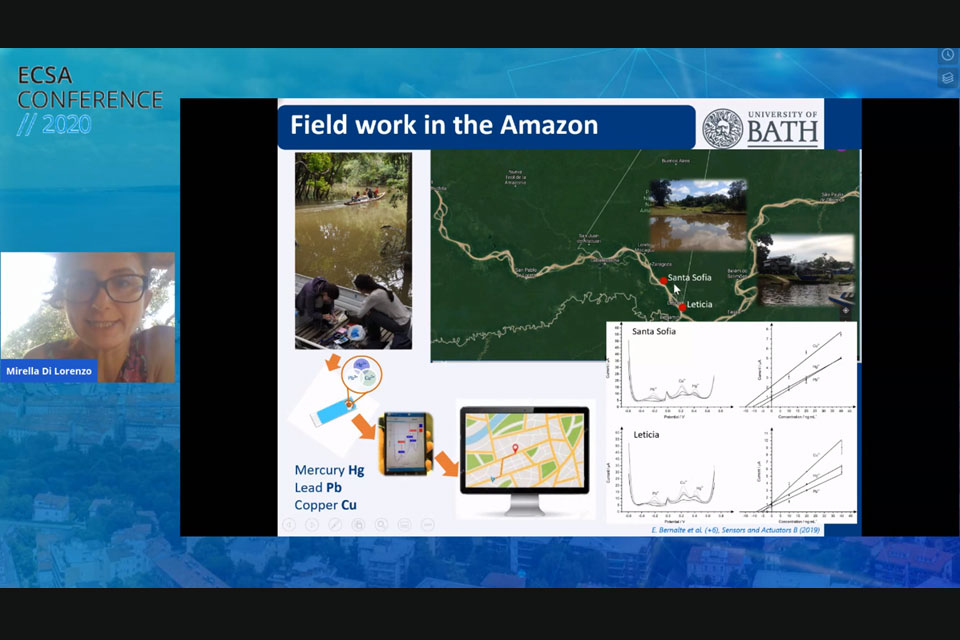

Dr Mirella Di Lorenzo (Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Bath) introduced her past work on an easy-to-use, low-cost water quality monitoring project in Colombia. Her project sought to assess water quality in areas of the Colombian Amazon affected by gold mining. Artisanal and small-scale gold mining has caused considerable environmental damage, and has led to pollution from mercury, which is used in the extraction process for gold. Mercury bioaccumulates in the environment, meaning that the toxic metal builds up in the tissue of organisms, most severely affecting animals at the top of the food chain. This is a particular problem in remote and poor areas of Colombia, where indigenous communities rely on rivers for drinking water and consume local fish.

Mirella explained that the Colombian government was not undertaking environmental monitoring in these areas, so it was important to equip local communities to monitor water for themselves. The team developed an integrated sensor for the real-time detection of mercury, lead, cadmium and copper. Measurements were collected, transferred to a web platform via a dedicated app and presented on an open-source, interactive map. Building trust with the local community was vital, with the objectives and significance of the work clearly explained, meanwhile any technology had to be intuitive and easy-to-use. The team learnt that technology co-developed with participants is most effective.

Prof Mazin Qumsiyeh of the University of Bethlehem’s Palestine Institute for Biodiversity and Sustainability, and founder of the Palestine Museum of Natural History, offered perspectives on research in a situation of occupation, and in engaging volunteers. Attracting and engaging young people with science is particularly important for Mazin and, through exploration and discovery, is a key objective of the Palestine Museum of Natural History. The Palestinian Action Network for the Planet was also established to mobilise volunteers and collaborate with international NGOs to effect change locally and globally. However, he explained that the challenges they face are complex, these include movement and access restrictions within Palestine and, by virtue of the conflict, also extend to difficulties in getting research accepted for publication in journals.

The environment is rarely considered a priority in conflict areas, nor for those living with their consequences. However, Mazin explained that, in spite of the wider societal threats of occupation, violence and poverty, motivating people to take part in environmental projects can be straightforward. In his case, he presents the environment as ‘heritage’ – cultural heritage and natural heritage. Because cultural heritage is intrinsically connected to the land, for those living under occupation, pride in culture and place can help motivate young people to reconnect with nature.

The work by Dr Mohamed Farah of ECOSOC, based in Mogadishu, provided another perspective from a conflict-affected region. Internet issues sadly prevented him joining us live – underscoring the challenges organisations in fragile settings face in transferring knowledge to the international community. We caught up with him after the event so that he could feed into this report.

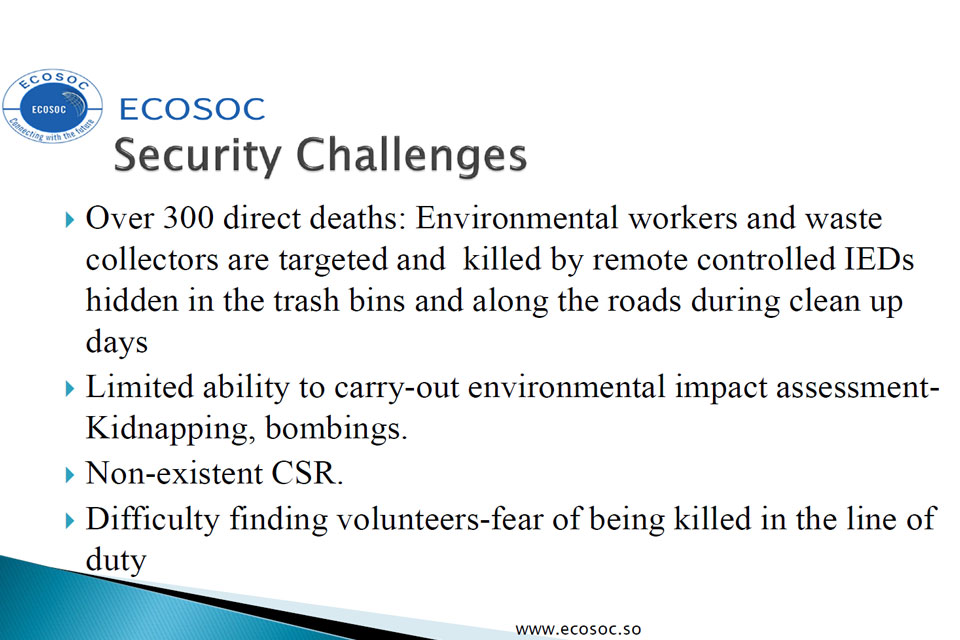

ECOSOC work in tackling plastic pollution, youth unemployment and waste, and are the local partner for World Cleanup Day. Somalia has been affected by civil war and conflict for decades, resulting in many environmental problems. Solid waste management and environmental governance is poor, with more than 60% of waste going uncollected and less than 1% being recycled. To tackle this problem, ECOSOC has developed a programme to manufacture construction products from plastic waste. Participants download an app developed by ECOSOC, which is used to notify the collection team about the type, and amount of waste to be collected. Waste collection trucks are then sent to the location.

In Somalia, environmental workers and waste collectors have been killed by remote controlled Improvised Explosive Devices hidden in waste bins and on roadsides. The challenges are therefore significant: on top of violence and intimidation, attracting volunteers and gaining their trust can be very difficult in conflict zones. There can be language and cultural issues to address and for some, lack of remuneration is a disincentive. For those at the forefront of environmental protection, good remuneration is indeed necessary to motivate participants to take such risks. Nonetheless, he felt that the lessons they had learned were readily transferable to other contexts. As well as the app technology, these included the role of community resilience, and the importance of building public awareness, and encouraging participation from the international community.

The discussion

We were lucky enough to receive some excellent questions from the floor, which in turn helped to draw out some essential principles for research in conflict-affected areas. For those of us who may be privileged outsiders, it is important to be aware of, and sensitive to, the challenges that conflicts create for local communities. This means that those planning citizen science projects in a conflict-affected area must develop a deep understanding of the background to the conflict, of the affected communities and the current situation. Teams need to understand the culture and know how best to engage with the community. Another observation was that, although it may be sometimes easier to involve governmental departments and those in power, this could affect and influence the direction of the project.

Our panellists felt that information and communication were key to success, as well as listening and connecting with local communities to build those all-important networks. In some cases, scientists have also realised early on in a project that they must adapt their role beyond science and learn to negotiate around a region’s politics.

One audience member asked whether there was any legal protection for the environment during conflicts, and this underscored the important role that scientists and citizen scientists can play. Current legal provisions intended to protect people and the environment from the impacts of conflict are weak. However, during the last decade significant progress has been made in strengthening the legal framework. This has included the development of principles to strengthen environmental protection before, during and after armed conflicts. While these are still to be finalised, it is clear that in future there will be a need for monitoring compliance with any strengthened framework.

The nature of armed conflicts means that some degree of environmental damage is inevitable, so we need a wide range of tools and resources to support those affected. Irrespective of the legal framework, there is already a pressing need to expand environmental data collection in these contexts to help protect affected communities.

There was agreement among the panel that environmental data can inform and empower people to effect change, leading to improved outcomes. But to prevent data from being weaponised or misreported, it must be transparent and reliable and, if possible, data collection should be collaborative – cooperation between communities across frontlines over shared environmental risks could form the basis of environmental peacebuilding. The sensitivity of data and potential risk of data misuse, however, must be managed and measures put in place to protect participants from harm. Using mobile apps rather than manual methods to collect data is one way to reduce risks, since data can be stored more securely and is more durable and robust.

Support in conflict-affected areas

Another question that the panellists addressed was whether there is a risk that the quality or reliability of data is compromised when using volunteers. Mazin’s experience in Palestine indicates that this is not the case. Their reliance on volunteering has not affected the success of the citizen science programmes, with participants also benefiting from local recognition, friendship and teamwork. Again, understanding local context here is important. In Somalia, where the risks for participants are so great, understandably many would not be willing to take part without payment.

And it’s not just scientists and local citizen scientists who can get involved. A project in eastern Ukraine that used an interactive Google maps platform to record buildings damaged by shelling showed that other stakeholders have a role to play. In that case it was a partnership between the UN Development Programme and a local technology company.

The panellists agreed that knowing that who is working on what, and where, would be a useful first step in connecting researchers in affected areas with external support from international researchers. Support from the wider citizen science community for programmes such as those in Palestine would be welcome, especially given the limited resources available locally.

If you are interested in supporting future citizen science projects in areas affected by armed conflict, have any ideas for future work or collaboration, please get in touch by completing our contact form. As a starting point, a network of citizen science specialists available to support work in conflict-affected areas would be an excellent outcome from the ESCA workshop.

Our thanks to the organisers at ESCA for hosting the conference and workshop under the current difficult circumstances. A recording of the workshop is available on ECSA’s Youtube Channel from Monday 19th October.

Linsey Cottrell is CEOBS’ Environmental Policy Officer.