Has the ICC just advanced accountability for wartime environmental damage?

Published: December, 2025 · Categories: Publications, Law and policy

The International Criminal Court has published a new policy on how environmental considerations can be integrated into its approach to humanity’s most serious crimes. Lydia Millar examines what the policy says, how it could contribute to accountability processes, and why it’s not the end of the story.

Between ambition and reality

The International Criminal Court’s (ICC) Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) has released its new Policy on Addressing Environmental Damage Through the Rome Statute, a document several years in the making and shaped through extensive expert consultations, civil society input, and internal drafting to clarify how the OTP will approach investigations and prosecutions involving environmental harm.

Its publication in December 2025 prompted a familiar question: will this actually make accountability for environmental war crimes more likely, or is it another well-intentioned but ultimately symbolic document? As ever with the ICC, the answer sits somewhere between ambition and political reality. The new policy displays a more scientifically sound understanding of environmental damage and takes a step towards meaningful pathways to accountability, but significant gaps remain.

It is important to note that the OTP’s policy does not address proposals to include a so-called fifth international crime of ecocide, and is limited to applying the existing crimes under the Rome Statute.

Below, we unpack how the policy reframes harm under the 1998 Rome Statute, how it approaches evidence, and where real-world constraints remain. As an example, we also explore how it might improve accountability for the real-world example of the destruction of Ukraine’s Khakovka Dam.

A broader understanding of environmental harm across Rome Statute crimes

Although the Rome Statute contains only one explicit reference to environmental damage, Article 8(2)(b)(iv)’s war crime of causing ‘widespread, long-term and severe’ harm, 1the new policy makes clear that environmental damage can be integral to the commission, assessment of the offence’s seriousness (or gravity of the offence), and evidentiary analysis of all Rome Statute crimes. Historically, ambiguity over what constitutes environmental harm has limited the Rome Statute’s practical reach. The policy seeks to address this gap by articulating a more comprehensive and scientifically grounded understanding of environmental damage relevant to genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and aggression.

Central to this shift is the adoption of an Earth-systems approach. Instead of treating the environment as a collection of discrete components such as forests, soil, or water, the policy conceptualises environmental systems as interconnected spheres. This mirrors the scientific consensus that conflict-related environmental harms unfold as system-wide disruptions, including contamination of watersheds, degradation of air quality, species loss, collapse of food webs, or impairment of ecosystem services.

The policy also emphasises harms to non-human inhabitants, and to cultural and spiritual relationships with the natural world. While it does not confer legal personality on nature, it recognises that environmental destruction affects far more than human survival or military utility. This broadens the conceptual space for assessing harm across all crimes within the Court’s jurisdiction, not only those explicitly referencing the environment.

Collectively, these shifts allow prosecutors to frame a much wider array of environmental impacts as legally relevant to Rome Statute crimes.

Crimes against humanity

The policy expands how environmental harm can serve as evidence of, or a constitutive element within, crimes against humanity. Importantly, these crimes do not need to occur in the context of an armed conflict. Under the policy, severe environmental degradation, such as destruction of water infrastructure, toxic contamination, or ecosystem collapse, may contribute to acts like persecution, forcible transfer, extermination, or ‘other inhumane acts.’2

The policy therefore provides a clearer analytical path for examining environmental harm in places such as Gaza, where extensive damage to wastewater plants, desalination facilities, and agricultural ecosystems has been widely reported by UN agencies and humanitarian organisations. While the ICC would still need to determine whether such harm forms part of a widespread or systematic attack against civilians, the policy ensures that these kinds of environmental impacts are treated as potentially relevant evidence rather than background context.

In addition, the policy’s operational guidance, encouraging the use of satellite imagery, environmental sampling, and ecological assessments, strengthens the OTP’s capacity to analyse destruction of life-supporting systems in both conflict and non-conflict situations. Environmental collapse in Gaza, for example, has been associated with large-scale displacement, loss of access to potable water, and long-term risks to public health. The policy allows prosecutors to consider whether such cascading harms contribute to coercive conditions amounting to crimes against humanity. Crucially, because these crimes do not require proof of an armed conflict, the ICC may examine environmental degradation arising from state practices or blockades even when hostilities fluctuate or cease.

Genocide

For genocide, the policy’s implications lie in recognising that environmental destruction may be used to commit, facilitate, or conceal genocidal acts, and likewise, genocide does not require an armed conflict. Environmental devastation can be relevant to the element of ‘deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about a group’s physical destruction,’ provided the specific intent to destroy a protected group can be proven.3

The policy broadens the evidentiary landscape by highlighting how destruction of water, sanitation, food systems, or habitability may be relevant to this inquiry. Once again in Gaza, where environmental collapse has reportedly left much of the territory with unsafe water, mounting waste, and damaged farmland, the policy allows the OTP to consider whether these harms relate to questions of intent or form part of a pattern of acts affecting a protected group, be it national, ethnic, religious, or racial, without presuming that they do.

The policy’s emphasis on cumulative and long-term impacts also matters. Environmental degradation that systematically undermines a population’s ability to survive, whether through contamination of water sources, destruction of cropland, or obliteration of critical infrastructure, may help contextualise alleged genocidal conduct when combined with other evidence. While the high threshold for proving genocidal intent remains unchanged, the policy gives prosecutors a more structured framework for evaluating whether environmental devastation contributes to, or evidences, genocidal conditions in both wartime and peacetime settings.

War crimes

The policy clarifies how environmental harm can be investigated as war crimes, but it also highlights persistent structural weaknesses in the Rome Statute, particularly the ambiguous standard in Article 8(2)(b)(iv). This provision applies only in international armed conflicts (IACs), such as the war between Russia and Ukraine, and requires proof that an attack was launched with knowledge that it would cause ‘widespread, long-term and severe’ environmental damage. Yet the Rome Statute and its Elements of Crimes offer no definition of these terms, leaving their interpretation to inconsistent state practice and guidance from authoritative yet non-binding instruments, such as the ICRC Guidelines on protection of natural environment in armed conflict, in absence of any jurisprudence.

The new policy does little to resolve this gap: while it encourages the use of scientific evidence and cumulative-impact analysis, it cannot overcome the fact that the threshold is cumulative, undefined, and extraordinarily high, making prosecutions under Article 8(2)(b)(iv) still highly unlikely. In this sense, the policy exposes, rather than cures, the fundamental indeterminacy that has long rendered this war crime largely dormant.

In contrast, war crimes committed in a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) may encompass conduct that involves or results in environmental harm, provided the act occurs ‘in the context of and is associated with’ the armed conflict, meaning the conflict must play a substantial part in the perpetrator’s ability, decision, purpose, or manner of committing the crime.4 Although article 8(2)(b)(iv) applies only in IACS, the policy makes clear that numerous NIAC war crimes, such as destroying or seizing the property of an adversary without military necessity (art. 8(2)(e)(xii)), unlawful deportation or transfer (art. 8(2)(e)(viii)), or cruel treatment (art. 8(2)(c)(i)), may be committed by means of or through acts causing environmental damage, including pollution, destruction of land, contamination of water sources, or seizure of natural resources.

The same environment-related war crimes available in NIACs also apply in IACs to the extent that the underlying conduct is criminalised, meaning that in addition to the single environment-specific war crime in IACs, a range of environment-related war crimes may also arise.

Such environmental harm is relevant both to establishing the actus reus (the act or conduct that is a constituent element of a crime), where the destruction of land, water, crops, or other natural resources constitutes prohibited ‘property’ or contributes to coercive displacement, and to assessing gravity, where the scale, nature, and long-term ecological impact of the damage may increase the seriousness of the offence. Accordingly, even absent a dedicated environmental war-crime provision in NIACs, environmentally destructive conduct can fall squarely within the Statute where it forms part of prohibited acts and meets the contextual nexus to the armed conflict.

The crime of aggression

The policy’s section on aggression makes clear that the crime of aggression acquires expanded environmental relevance under the new framework. The policy emphasises that aggression ‘poses a unique threat to the natural environment,’ both because aggressive uses of armed force typically cause direct ecological destruction and because they trigger broader armed conflicts that compound environmental harm.5 It also explicitly mentions harm to the atmosphere, of relevance to the increasing attention on conflict greenhouse gas emissions.

While the elements of the crime of aggression under article 8bis remain unchanged, the policy explicitly integrates environmental damage into the assessment of whether an act of aggression constitutes a ‘manifest’ violation of the UN Charter.6 It states that when evaluating the character, gravity, and scale of an alleged act of aggression under article 8bis(1),7 the OTP will take into account the nature, extent, and potential irreversibility of environmental damage, including the number and kind of human and non-human victims affected. The policy also underscores that intentionally destroying or damaging the environment in another state constitutes a particularly grave use of force, reinforcing that environmental harm may significantly contribute to meeting the Statute’s ‘manifest violation’ threshold. Accordingly, while the policy does not alter the legal definition of aggression, it substantively affects how the OTP evaluates, prioritises, and characterises acts of aggression, ensuring that environmental consequences play a central role in charging decisions and gravity assessments.

A stronger evidentiary model

One of the most transformative features of the new policy is its modernised evidentiary framework. Environmental cases have historically been hindered by weak data collection, inadequate chain-of-custody procedures, and limited use of scientific methods tailored to conflict settings.

The policy commits the OTP to interdisciplinary investigations drawing on climate science, environmental forensics, toxicology, public health, satellite imaging, remote sensing, ecological field surveys, Indigenous and local knowledge, and supply-chain analysis. This significantly expands the kinds of evidence available to establish the scope and foreseeability of harm.

The policy also normalises reliance on open-source intelligence and civil-society documentation. This lowers barriers to early evidence collection and better reflects the realities of conflict environments where ground access may be impossible.

Importantly, the policy implicitly endorses a best-available-science standard. Because environmental harms evolve over time and may be only partially visible at the moment of attack, allowing prosecutors to draw on modelling, projections, and risk assessments helps establish foreseeability even when harm is still unfolding.

Example: Would the OTP’s policy make accountability for the environmental consequences of the destruction of Ukraine’s Kakhovka Dam more likely?

Yes, but only modestly, and primarily by lowering practical barriers to treating the Kakhovka Dam’s destruction as an environmental crime within existing Rome Statute provisions, rather than by expanding the ICC’s legal jurisdiction.

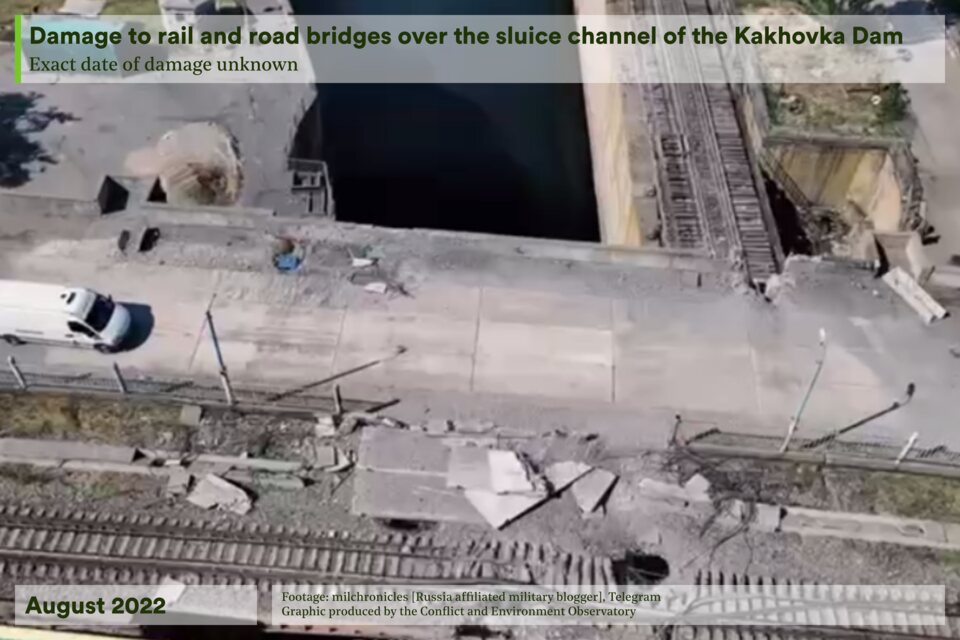

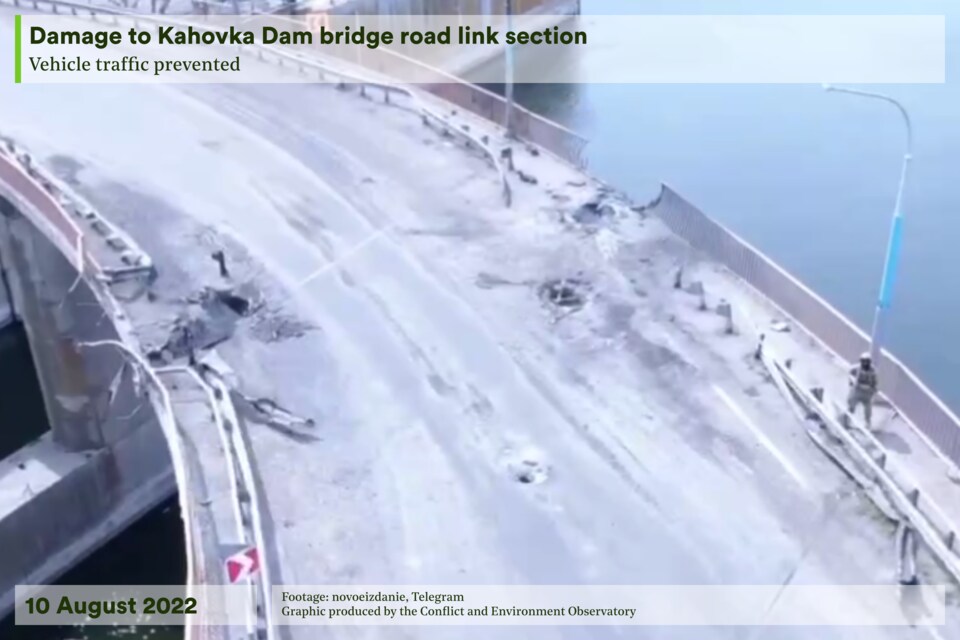

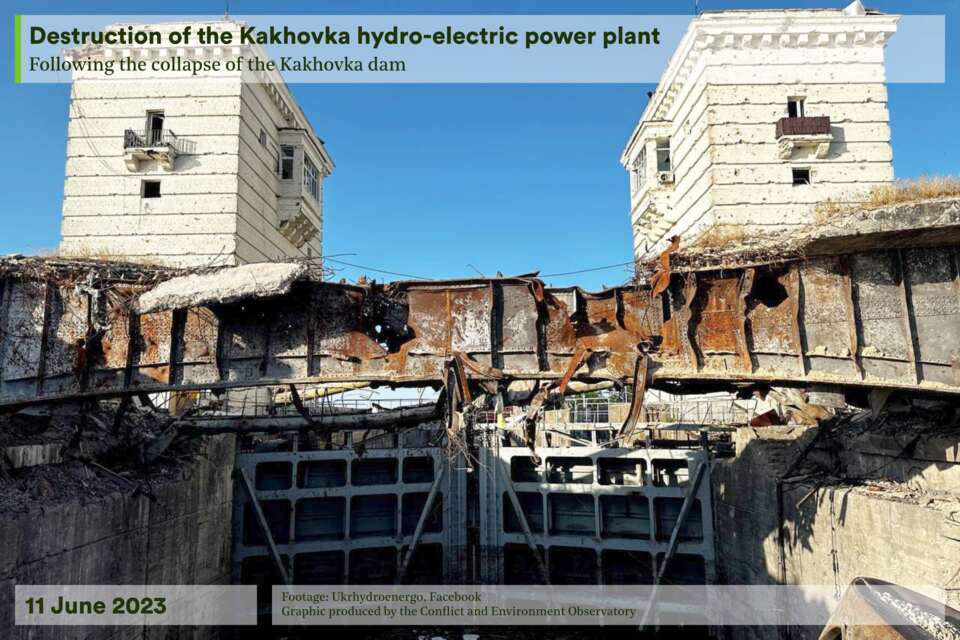

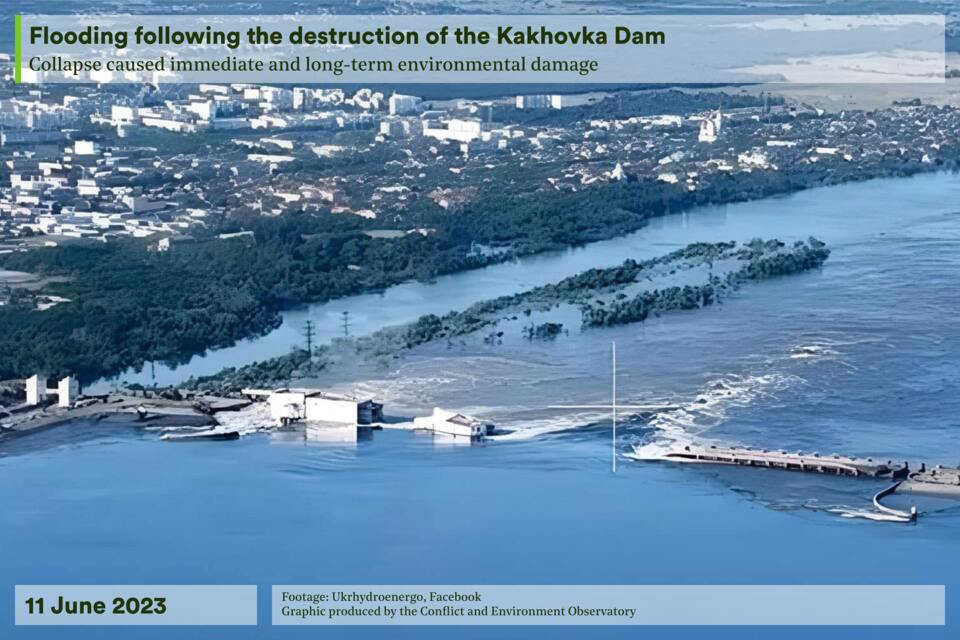

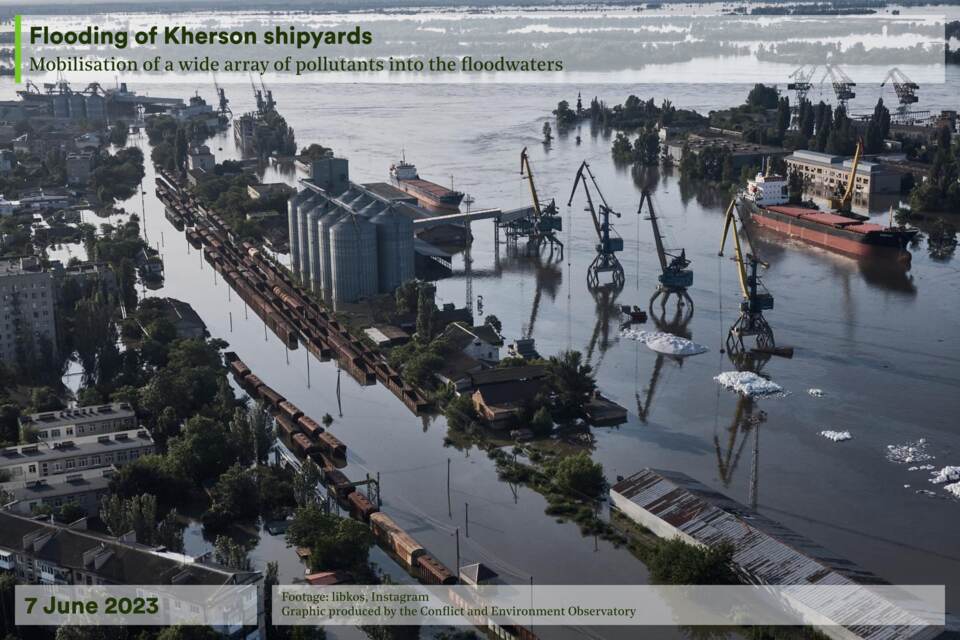

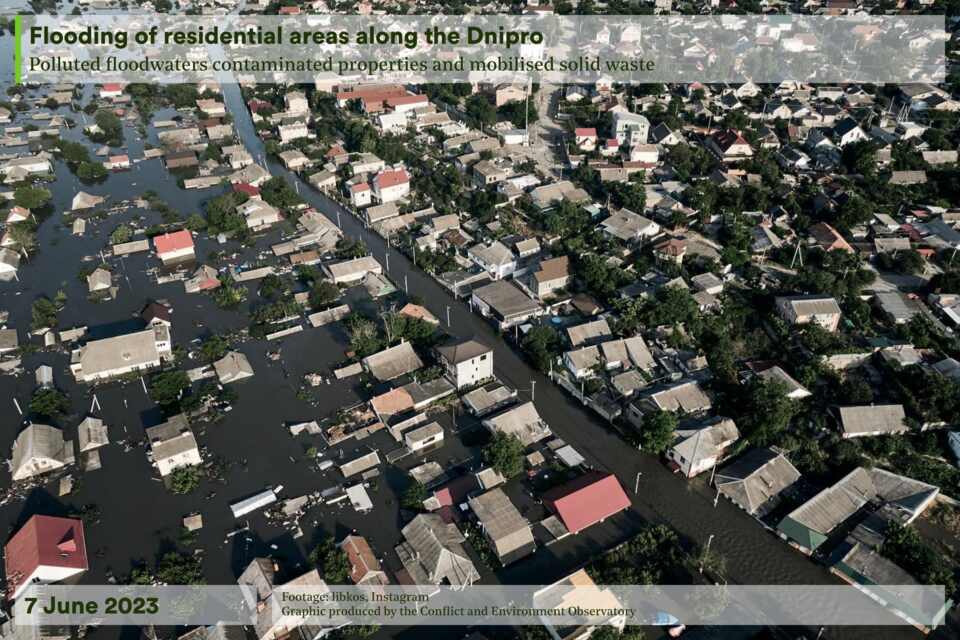

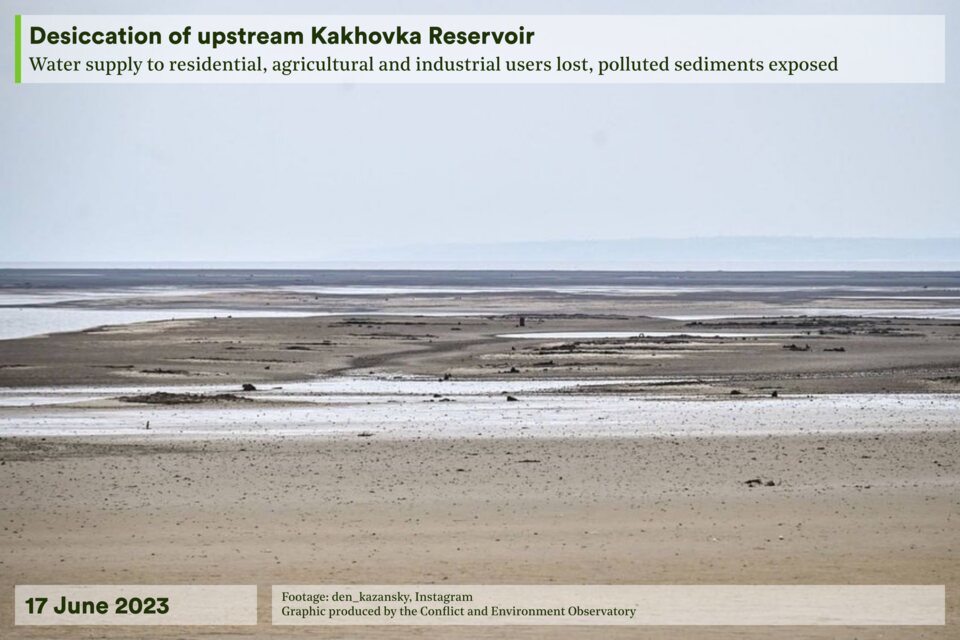

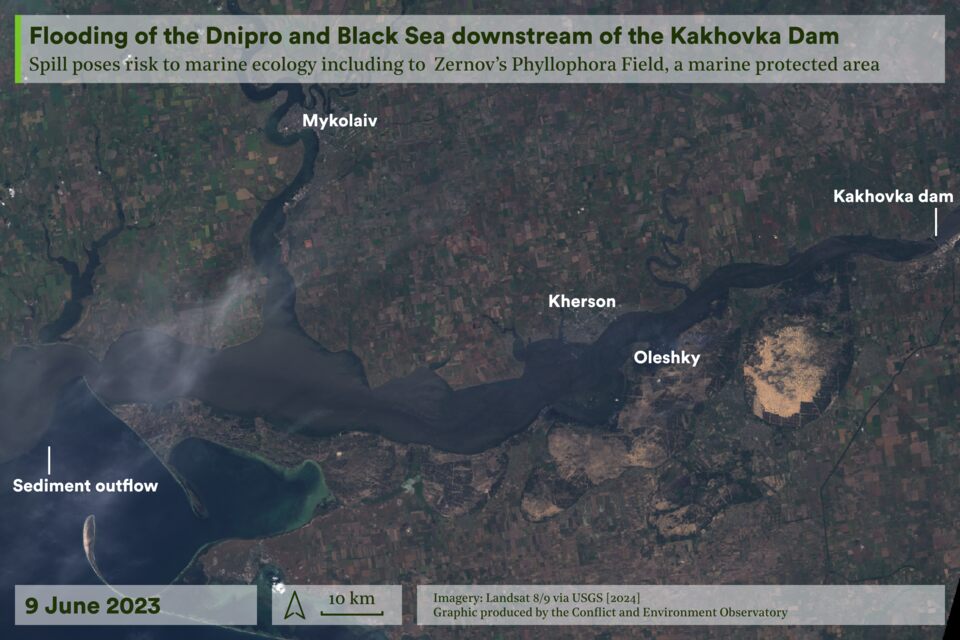

The new policy clarifies that environmental damage can play a role across genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, not only under the narrow Article 8(2)(b)(iv) provision. This matters because the Kakhovka Dam collapse produced widescale flooding, long-term hydrological disruption, destruction of habitats, and downstream water scarcity. These impacts are well documented in CEOBS’ assessment of harm, and in many other studies, including impacts on the Dnipro reservoir system, agriculture, drinking water supplies, protected areas, and the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant’s cooling systems.

By emphasising the Rome Statute’s anthropocentric orientation but expanding environmental considerations within admissibility, gravity, contextual elements, and evidence-gathering, the policy makes it more likely that such cascading harms (to civilians, ecosystems, and essential services) are treated as part of a prosecutable criminal pattern rather than collateral background. The policy’s focus on interdisciplinarity, long-term and intergenerational impacts, and cumulative harm directly aligns with CEOBS’ conclusions that the dam’s collapse created compound, multi-system degradation that cannot be understood only through a narrow military-necessity lens.

However, the policy does not change the Rome Statute thresholds that make environmental war crimes hard to prosecute, especially proving intent, sufficient connection between the environmental harm and the underlying attack, and ‘widespread, long-term and severe’ damage under Article 8(2)(b)(iv). For Kakhovka, attribution remains contested, hydrological and ecological impacts will unfold over years, and determining the severity of some consequences, such as salinisation, soil degradation, and species loss will require sustained scientific monitoring.

The policy helps the ICC integrate precisely this kind of environmental science into investigations, encourages cooperation with civil society actors like CEOBS, and signals that destruction of critical water infrastructure may also fall under other crimes, for example, forcible displacement, persecution, extermination, or unlawful attacks on civilian objects. This broader framing allows prosecutors to capture the full human–environmental consequences of the dam’s collapse even if the high Article 8(2)(b)(iv) threshold is not met. In this sense, accountability is more likely than before, not because new crimes have been created, but because the ICC is now institutionally committed to recognising, evidencing, and prioritising the environmental dimensions of conduct that already falls within its jurisdiction.

Reality check: process and politics still matter

Despite its ambition, the policy faces several structural constraints.

First, the ICC is resource-limited. Environmental investigations require specialised expertise, long-term monitoring, and field research that may be prohibitively expensive. Second, cooperation from states remains a central obstacle. Many of the worst environmental harms occur in conflicts where states are themselves implicated or unwilling to assist investigators. Third, geopolitics shapes which situations the ICC can investigate. Jurisdictional gaps mean that many environmentally destructive conflicts fall outside the Court’s reach, and political pressure can impede investigations even where jurisdiction exists.

Finally, Article 8(2)(b)(iv) retains an exceptionally high legal threshold, and is unlikely to become a commonly charged provision. In practice, this reinforces the policy’s approach that accountability for environmental harm will more plausibly arise through other Rome Statute crimes rather than relying solely on the environment-specific war crime. Until the Rome Statute is amended or international jurisprudence evolves, only the most serious and unambiguous cases will cross Article 8(2)(b)(iv).

Conclusion

The OTP’s new Policy on Addressing Environmental Damage Through the Rome Statute marks a substantive evolution in how the ICC understands and investigates environmental harm, but its transformative potential remains constrained by the Statute’s existing architecture and by political realities.

By adopting an Earth-systems perspective, expanding the evidentiary landscape, and clarifying that environmental damage is relevant across all core international crimes, the policy provides prosecutors with a far more sophisticated toolkit than ever before. It signals institutional willingness to treat environmental destruction not as collateral or peripheral, but as a central component of human harm and criminal conduct. Its alignment with best-available science and its explicit recognition of cumulative, cascading, and intergenerational impacts are particularly consequential, enabling the Court to capture the true scale of environmental degradation in contemporary conflicts, from the flooding and hydrological collapse caused by the Kakhovka Dam breach to the systemic environmental degradation seen in Gaza and other conflict zones.

Yet ambition is not the same as capability. The policy cannot resolve longstanding doctrinal limitations, such as the absence of definitions for ‘widespread, long-term and severe’ in Article 8(2)(b)(iv), the lack of an equivalent environmental war crime in NIACs, or the high thresholds for proving genocidal intent. Nor can it overcome the ICC’s structural dependence on state cooperation, its resource constraints, or the geopolitical pressures that shape which cases are pursued. What it can do — and does — is expand the interpretive and evidentiary space within which environmental harm can meaningfully influence prosecutorial strategy. In this sense, the policy should be understood as an important step towards environmental accountability, but not its culmination: a signal of direction rather than a guarantee of outcomes.

The real test will lie in whether states, civil society, and international institutions mobilise the political and material support required for the ICC to translate this more ambitious vision into practice.

Lydia Millar is an intern at CEOBS and a PhD candidate at Queen’s University Belfast. Her thesis is on the usefulness of open source information in identifying victims of conflict-related environmental harm for the purposes of transitional justice. Follow her on Linkedin here. Thanks to Dr Stavros Pantazopoulos for his insightful comments on this post. If you find our work useful, please consider making a donation so that we can continue it.

- Article 8(2)(b)(iv) of the Rome Statute 1998 states that it is a war crime to intentionally launch ‘an attack in the knowledge that such attack will cause incidental loss of life or injury to civilians or damage to civilian objects or widespread, long-term and severe damage to the natural environment which would be clearly excessive in relation to the concrete and direct overall military advantage anticipated.’

- Rome Statute, Article 7.

- Rome Statute, Article 6(c).

- The OTP’s policy, p 19.

- The OTP’s policy, p 23.

- Ibid.

- Article 8bis(1) states: ‘For the purpose of this Statute, “crime of aggression” means the planning, preparation, initiation or execution, by a person in a position effectively to exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of a State, of an act of aggression which, by its character, gravity and scale, constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.’