The revisions to the draft principles on environmental protection in situations of occupation have improved them considerably but gaps remain that should be addressed.

The International Law Commission has completed its review of the draft principles on environmental protection in situations of occupation that were proposed by its Special Rapporteur in April. The Commission, and its drafting committee, have made a number of changes to the principles, and in doing so have made some notable improvements. This blog by CEOBS and Al-Haq takes a look at the revised principles and reflects on their relevance using examples from current occupations, finding that there is still room for improvement.

Background

The fourth report in the International Law Commission’s (ILC) ongoing study on the Protection of the environment in relation to armed conflicts was the first by its new Special Rapporteur Dr Marja Lehto. It was also the first to focus on a specific theme – that of occupation. In CEOBS’ blog on the new principles in June, a number of concerns were raised about the proposed principles, some of which also arose during the four plenary debates in the ILC in July (records of which are available here, here, here and here).

One of the most obvious changes endorsed by the ILC’s drafting committee is to the focus of the principles, which have shifted from obligations on the “occupying state”, to obligations on the “occupying power” – this is in line with the terminology of Article 45 of the Hague Regulations (1907), and Article 4 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949). This also reflects the growing number of cases where coalitions, or regional and international organisations, have found themselves to be de facto occupying administrations. This change perhaps exemplifies the wider debate within the plenary, which saw early 20th Century occupation law confronted by developments in human rights and environmental law, international environmental protection norms, and the diverse characteristics of recent and contemporary occupations, few of which were likely envisaged during the drafting of either the Hague Regulations or the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Another common theme was the dynamic between the conservationist principle – that an occupying power’s ability to change the legal framework and systems of governance within an occupied territory be limited, and the requirement to protect the environment, rights and wellbeing of the occupied population. For example by modifying environmental regulations or making systemic changes to governance structures. Some members raised the example of the US-led coalition’s 2003 occupation of Iraq, where a derogation from this principle was afforded by Security Council resolution 1483, as possible evidence of an evolution towards the controversial idea of “transformative occupations”.

Nevertheless, this is dangerous territory as it could be used to legitimise illegal occupations. The revised principles are therefore conservationist in tone but do provide some latitude within the limits of the law of occupation, with the ILC’s drafting committee report arguing that it was: “…appropriate to retain this explicit reference since the Geneva Conventions contained provisions specifically addressing the maintenance of the institutions of the occupied territory, and institutional collapse was a common feature of conflict situations.”

The closely linked debate over the role of occupying powers in respecting and protecting the environmental human rights of populations under their control was also examined at length in the plenary. As with previous debates, the question of lex specialis featured heavily, with a consensus emerging that human rights law could, and should, plug gaps in the applicable international humanitarian law on issues where it was silent, and clarify obligations where it was unclear. The chief focus on this was the right to health and its relationship with the occupiers’ obligation to “restore and ensure public order and safety”, or the more expansive “l’ordre et la vie publics” in the authentic French text of the Hague Regulations – an obligation that grows in importance in line with the length of the occupation.

Although the plenary discussed how obligations might develop over prolonged occupations, particularly the question of human rights as the security situation stabilised, the question was not addressed in the revised principles, or in the report of the drafting committee. It is unclear whether or how the question of the temporal development of human rights or environmental obligations will be dealt with in the commentary.

ILC members ultimately forwarded all three draft principles to the drafting committee who, together with the Special Rapporteur, sought to modify them in line with the views expressed in the plenary. The original and revised principles are available below, together with our observations on how they relate to some current examples of occupation, as well as some thoughts on the principles in the context of the progressive development of occupation law.

Original draft principle 19

1. Environmental considerations shall be taken into account by the occupying State in the administration of the occupied territory, including in any adjacent maritime areas over which the territorial State is entitled to exercise sovereign rights.

2. An occupying State shall, unless absolutely prevented, respect the legislation of the occupied territory pertaining to the protection of the environment.

Revised Draft principle 19

General obligations of an Occupying Power

1. An Occupying Power shall respect and protect the environment of the occupied territory in accordance with applicable international law and take environmental considerations into account in the administration of such territory.

2. An Occupying Power shall take appropriate measures to prevent significant harm to the environment of the occupied territory that is likely to prejudice the health and well-being of the population of the occupied territory.

3. An Occupying Power shall respect the law and institutions of the occupied territory concerning the protection of the environment and may only introduce changes within the limits provided by the law of armed conflict.

Rights over maritime areas

The original DP19 includes a progressive reference to the jurisdiction of the occupying power over “adjacent maritime areas over which the territorial State is entitled to exercise sovereign rights”. The intersection between occupation law and the law of the sea is not well established, a gap which is particularly evident in prolonged military occupations. Although a state has rights, which accrue over the continental shelf, and which exist ipso facto and ab initio, by virtue of its sovereignty over the land (North Sea Continental Shelf Case) – the issue of the maritime rights of the occupied state is not as straightforward.

In 2014, Turkey submitted a note verbale to the UN Secretary General, establishing the points of delimitation of the continental shelf between Turkey and the unrecognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The attempted delimitation of the sea off occupied Northern Cyprus conferred a disproportionately large maritime area to Turkey, the occupying power. The delimitation attempt also highlighted the necessity for additional research around the intersection between the law of the sea and the law of belligerent occupation.1

Maritime considerations have arisen in many contemporary prolonged occupations. The ousted sovereign, may not have agreed, and may be prevented from agreeing, an exclusive economic zone (EEZ). For example, the Gaza-Jericho Agreement, concluded between Israel and the PLO establishes a Gaza Maritime Zone – a limited regime granting Palestinian maritime access to a distance of 20 nautical miles (nm) – for “fishing, recreation and economic activities” but this falls far short of the potential 200nm EEZ delimitations that states may customarily conclude. Critically, the latter bilateral agreement has no legal basis under the law of the sea. It is further compromised by the imposition of Israel’s unlawful naval blockade and its closure of the Gaza Strip, ensuring that Palestinians are prevented from accessing the 60nm continental shelf extending from its coast. Meanwhile, in 2005, Israel and Egypt concluded a Memorandum of Understanding for the laying of the El Arish gas import pipeline, some 13nm off the Gaza (and along the entire 40km Palestinian) coast, to pipe gas from Egypt to Israel, an area that falls outside environmental regulation under local Palestinian law.

Environmental considerations in situations of occupation

We remain concerned about what constitute “environmental considerations” in DP19.1 and the question of what measures are deemed appropriate to minimise risks to public and environmental health in DP19.2. Current occupations demonstrate why they are needed but they also show that they can sometimes be interpreted in ways that are counterproductive. For example, some occupiers manipulate environmental considerations as a tactic to unlawfully and permanently appropriate private and public immovable property in occupied territory. In the OPT, Israel has designated Wadi Al-Qilt and Ein Fashkha in the Northern Jordan Valley and Dead Sea areas as nature reserves, thereby making it impossible for the local Palestinian population to obtain building permits. Israeli law on national parks prohibits any “…building activity or any other activity that could in the opinion of the Authority hinder the designation of the area as a national park or as a nature reserve… other than with the approval of the Authority.”2 Critically, the nature reserves are strategically designated besides or close to settlements, to provide for future settlement expansion, while dispossessing the protected Palestinian population of their land and leading to forcible transfer.

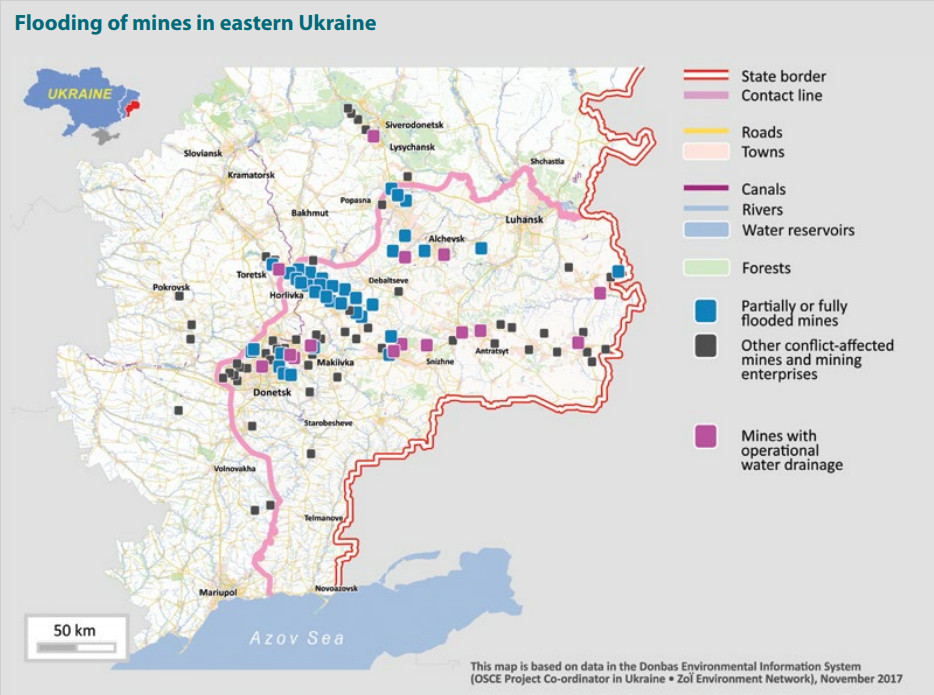

In the context of the conflict in Ukraine, and as occupation law only applies in international armed conflicts, one immediate challenge is the classification of the conflict. For the occupation and illegal annexation of Crimea, direct Russian involvement satisfies its classification as an international armed conflict. For the Donbas region, where Russia has refused to acknowledge its involvement, in spite of extensive monitoring data to the contrary, the International Criminal Court has suggested that parallel international and non-international conflicts have been active since 2014. In this case Russia could, for example under 19.1, be obliged to ensure that parties under its control do not damage of disrupt environmentally hazardous industrial or mining infrastructure, cause damage to protected areas, and ensure that the de facto administrations in the Donbas are capable of performing adequate levels of environmental oversight. Nevertheless, the situation in the Donbas raises a number of questions over the future applicability and implementation of the principles.

The issue of environmental considerations, and in particular the response of occupying powers to environmental emergencies, came to the fore in Crimea at the end of August. The release of sulphur compounds from the Crimean Titan titanium plant near Armyansk exposed the town, its population and surrounding agricultural areas to sulphuric acid fallout. The Russian-backed Crimean authorities played down the risks before eventually evacuating children from the town. The cause of the release from the plant, which abuts the new border between occupied Crimea and Ukraine is still unclear. The occupying authorities have blamed a lack of water caused by Ukraine’s closure of the North-Crimean canal, exacerbated by a prolonged drought, which allowed lakes containing acid discharges to dry out. However satellite data reviewed by CEOBS indicates that drying of the lakes is common during the summer. The Titan plant installed sulphuric acid production equipment in 2012 and it may be that the release came directly from the plant. Within days the incident had become highly politicised and at the time of writing its cause was still unclear.

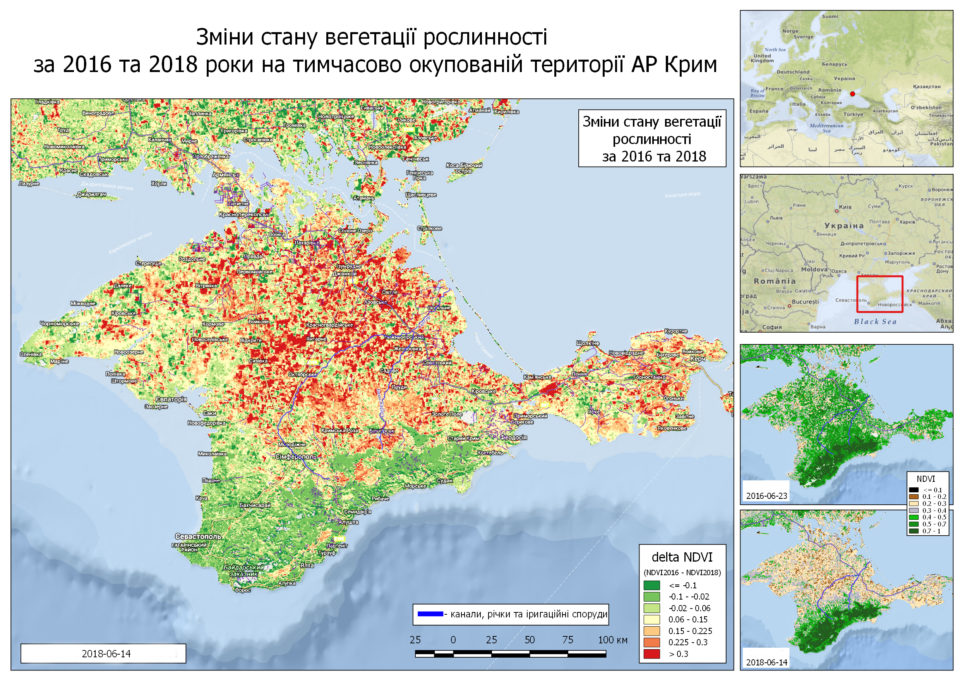

Meanwhile in eastern Crimea, concerns have been raised over the environmental impact of the construction of the Kerch Strait Bridge, and over military activities in protected areas adjacent to the strait. Although the Sea of Azov was facing considerable environmental pressures prior to the conflict, environmental activists argue that the bridge will exacerbate existing issues linked to water circulation, biodiversity loss and erosion – the sea is home to several Ramsar designated coastal wetlands. However Russia might justify the bridge’s construction on the basis of military necessity. Ukraine’s Ministry of Temporarily Occupied Territories has also accused Russia of neglecting and damaging the Crimea’s vegetation and soils. Ukraine’s decision to halt the flow of the North-Crimean canal following the annexation, in a dispute over unpaid bills and the legitimisation of the occupation, has led to a greater reliance on groundwater abstraction. Ukraine argues that its use has led to widespread mineralisation of agricultural soils that will take at least a decade to remedy.

While the neglect of environmental governance appears relatively common during occupations, those marked by recurring periods of violence also see direct damage to the environment and with it health risks for the occupied population. For example, Israel’s military attacks on Gaza’s wastewater treatment plant have been extensively outlined by the United Nations Human Rights Council Commissions of Inquiry (see here and here). Repeated periods of intense infrastructure damage, and the restrictions the closure poses for the availability of spare parts and technical assistance have led to reverberating effects for Gaza’s environmental quality, with direct consequences for public health. In August 2017, a 5-year old child died and others were hospitalised in Gaza after swimming in the sewage polluted waters off the Gaza Strip.

Original draft principle 20

An occupying State shall administer natural resources in an occupied territory in a way that ensures their sustainable use and minimizes environmental harm.

Revised draft principle 20

Sustainable use of natural resources

To the extent that an Occupying Power is permitted to administer and use the natural resources in an occupied territory, for the benefit of the population of the occupied territory and for other lawful purposes under the law of armed conflict, it shall do so in a way that ensures their sustainable use and minimizes environmental harm.

On the sustainable use of finite resources

The tone of DP20 is framed somewhat permissively, and contrasts with the more prohibitive language of Article 55 of the Hague Regulations, where the occupying power “…shall be regarded only as administrator and usufructuary of public buildings, real estate, forests, and agricultural estates belonging to the hostile state, and situated in the occupied country”, whereupon it “…must safeguard the capital of these properties, and administer them in accordance with the rules of usufruct.” Notably, Article 55 of the Hague Regulations is one of the few articles which does not contain a military security exception providing for use in cases of “military need” or “military operations”, and can be considered a much more stringent protection in this regard.

While there has been some evolution in the interpretation of usufruct from its expansive reading in Roman law, to include all mineral and quarried resources, the understanding now that such resources are finite and non-renewable, further confines the use by the belligerent occupant of the resources of the occupied territory. The opening of new mines and the excessive depletion of already opened mines are factors for consideration in relation to defining “sustainable use”. Therefore a strong position in the commentaries on the opening of new mines would be welcome.

For the benefit of the occupied population

The inclusion of “for the benefit of the occupied population” as a principle might go some way towards ensuring that the resources of the occupied territory are not exploited. However, this principle was not specifically written into Article 55, which protected the assets of the occupied state for the returning sovereign. Although the occupier does have an obligation under Article 43 of the Hague Regulations to administer territory in the interests of the occupied population, the potential for abuse of the principle is of concern.

For example, since 1967, Israel has granted licenses to commercial Israeli quarries to open and exploit a number of new sites across the occupied West Bank. In Yesh Din v. The Commander of the IDF Forces in the West Bank the Israeli High Court of Justice found that ceasing quarrying activities in the West Bank would inter alia damage the Palestinian population and economy. The West Bank’s quarries are being exhausted at a rate of 7.2bn tons a year, amounting to a serious and permanent loss to the State of Palestine. But it was argued that the closure of the quarries might impact the livelihoods of some 200 Palestinian quarry workers.

The critical question is who decides what use is for the benefit of the occupied population, the occupier, or the political representatives of the occupied population, or the occupied population itself? Who balances the competing interests? The courts of the occupier might not serve the interests of justice well. And how are the interests balanced? Excessive usufructs may amount to the war crime of pillage, and it would be useful if the draft principles would examine this issue of liability, and in particular that of both state and non-state actors who through their acts or omissions pursue unsustainable practices or cause environmental harm.

The protected population

More consideration is also needed in relation to the use of the terminology surrounding the “protected population” in DP19 and DP20. There have been cases where occupiers have distorted the protections afforded under the Fourth Geneva Convention for the protected occupied population to apply equally to settler populations. These settlers are unlawfully transferred into the occupied territory for the purpose of colonisation, and then considered as part of the population of the occupied territory.

The potential for this type of distortion should be removed from the draft principles. In this respect the language in the revised draft principles 19.2 and 20 should be modified from the broad “population of the occupied territory” to the “protected population”. This terminology, which is used in the Fourth Geneva Convention, applies to persons who, “at a given moment and in any manner whatsoever, find themselves, in case of a conflict or occupation, in the hands of a Party to the conflict or Occupying Power of which they are not nationals” (emphasis added).

Although the ILC’s earlier DP6 from its third report provides for appropriate measures to protect the environment of indigenous peoples, there is a lack of an authoritative definition on who is an indigenous person. No definition is provided in the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; while the ILO’s Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention (1989) provides only a loose definition, which includes tribal peoples, peoples inhabiting a country at the time of colonisation, and those who self-identify as indigenous. Additionally, the definition of an indigenous person in DP6 should be clearly explained, as should how this relates to the “protected population” in the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Original draft principle 21

An occupying State shall use all the means at its disposal to ensure that activities in the occupied territory do not cause significant damage to the environment of another State or to areas beyond national jurisdiction.

Revised draft principle 21

Due diligence

An Occupying Power shall exercise due diligence to ensure that activities in the occupied territory do not cause significant harm to the environment of areas beyond the occupied territory.

Transboundary harm goes both ways

Turning again to eastern Ukraine, there have been several cases where military actions, the absence of regulatory control, or decisions by the de facto administration in the Donbas, have threatened transboundary harm. One case that has received considerable attention recently is the YunKom mine, which was the site of an underground nuclear detonation in 1979. The decision by the Donbas authorities to switch off pumps preventing the spread of potentially contaminated water into groundwater aquifers, ostensibly as a cost saving measure, has provoked significant concern. The OSCE had earlier cautioned that: “Any present destabilisation of the mine via flooding could release up to 500 cubic metres of radiation-contaminated mine waters into the ground water table.” Similar concerns exist over groundwater contamination and subsidence linked to the cessation of pumping at many of the region’s ageing coal mines, the impact of which would be felt beyond the current line of contact.

But while the wording of DP21 focuses specifically on due diligence over harms that may be felt beyond the occupied territory, where the occupying power’s territory is adjacent to the occupied territory, it is silent on the question of harms caused on the occupier’s territory that cause damage to the occupied territory. For example, the inequitable use of shared water resources between Israel and the OPT, where pollution and over abstraction in Israeli areas impact Palestinian access to water, or Israel’s granting of licenses to companies to frack in areas on the Israeli side of the Green Line, which had “…the potential to cause extreme environmental damage”. Similarly, in 2010, and following a refusal by Israel’s National Planning and Building Commission to locate a hazardous gas storage facility in the territorial waters off the coast of Israel due to environmental considerations, the Ministerial Committee on Interior Affairs instead approved its construction beyond Israel’s territorial waters and in the contiguous zone, in close proximity to the Gaza Strip, where local environmental regulations did not apply.

Final thoughts

In many respects, the new draft principles honour the existing conservationist principle underpinning occupation law. However, there are some new departures, including the codification of the “for the benefit of the occupied population” principle in relation to immovable natural resources, and also the promise of further commentary analysis of the occupier’s responsibilities over adjacent maritime areas, an area not well researched. However as they stand, the draft principles are perhaps overly narrow. In addition to the issues outlined above, the role of third states in respecting and ensuring respect for international humanitarian law, including environmental considerations – an important reciprocal obligation in international humanitarian law – is notably absent.

Nearly 111 years since the adoption of the Hague Regulations, and 69 years since the adoption of the Fourth Geneva Convention, the ILC’s draft principles are the most recent, and perhaps significant, examination of the law of belligerent occupation since the 1977 Additional Protocols. Yet there have been normative developments since then that the draft principles fail to engage with. For example, it would be useful if the principles reflected the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, norms on the role of enterprises in respecting international humanitarian law, and corporate complicity in gross human rights abuses and environmental crimes. This is an area where the principles could have a significant impact on the ground.

States will have an opportunity to have their say on the revised principles during the annual debate on the work of the ILC in the UN General Assembly’s Sixth Committee in November. As with previous years, it is vital that the ILC’s outputs are tested against the lived experiences of states affected by conflict, and it is our hope that states currently or recently affected by occupation will present their views during the debate.

Dr. Susan Power is the Head of Legal Research and Advocacy in the Legal Research and Advocacy Department at Al-Haq. Doug Weir is the Research and Policy Director at the Conflict and Environment Observatory.

- Susan Power, “Occupying the Continental Shelf? – A Note Considering the Status of the Continental Shelf Delimitation Agreement Concluded Between Turkey and the TRNC during the Belligerent Occupation of Northern Cyprus” 9 (2014) Irish Yearbook of International Law.

- National Parks, Nature Reserves, National Sites and Memorial Sites Law, 5758-1998, Israel, Article 25(a), unofficial translation available here